Dear Henry Tate,

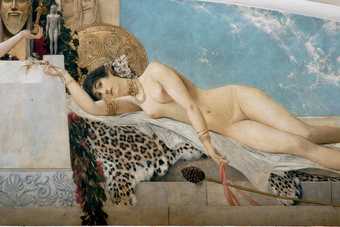

From the late 1960s Alighiero e Boetti produced embroidered maps and text works in collaboration with local craftsmen in Kabul, Afganistan, until the Soviet invasion forced him to move production to Peshawar, Pakistan. The texts he included, such as ‘to leave certainty for uncertainty’, now have an eerie ring to them in the post-9/11 climate. At the time, however, they were produced, as Brooks Adams writes, with ‘a runic, laid-back grace’. The same could not be said for master of erotic theatre Gustav Klimt, whose image and career was skilfully managed behind the scenes. Timing often helps – Klimt’s passion for the female form coincided with Freud’s theories of the unconscious – so his imagery struck a nerve. It was a period made particularly exciting by the old Viennese appetite for irony and ambiguity, not only among fellow artists, but also with their forward-looking patrons who didn’t seem to mind the idea of Klimt expressing the sexual energy of their wives on canvas.

The radical late 1960s English group King Mob preferred the platform of political revolution, tapping into the international mood of that era, and, as Hari Kunzru explains, their actions were ‘witty, carnivalesque and confrontational’. Now their archive is part of Tate’s collection. There is a different kind of confrontation in the work of Cy Twombly, who, as John Berger has written, ‘visualises with living colours the silent space that exists between and around worlds’. He celebrates his 80th birthday with a retrospective at Tate Modern featuring several series of paintings (and sculptures) from the 1950s to the present day. Happy birthday.

Bice Curiger and Simon Grant