Herbert Lachmayer

The Viennese avant-garde, that began around 1880, could be described as implosive. The catholic, conservative, more or less aristocratic or bourgeois society of these times perpetuated very rigid moral and cultural values in order to repress social emancipation with authority and confidence. The avant-garde reacted against this ridiculous conservatism through the use of irony and ambiguity. Since the eighteenth century the double-meaning of words had been a point of discussion – for example, think of Da Ponte’s libretti for Mozart. The libretto of Cosi Fan Tutte is full of erotic ambiguities: a simple sentence can include a very insinuating sexual allusion referring to the Neopolitanian slang which was well known by Da Ponte. The use of ambiguity in everyday language was a subversive strategy to challenge authorities generally – especially the church and the aristocracy. Ambiguity had also been a poetical instrument used to cross the border between the conscious and unconscious.

This was one aspect of Viennese mentality which supported the theory of the unconscious by Sigmund Freud – it’s not a coincidence that this happened in Vienna and not in Bern, for example. Secondly, this implosive avant-garde made a great effort to establish radical ideas in the arts, philosophy and science in the face of the ruthless arrogance and repression of Viennese conservative mentalities. Thus, the founding systems of Sigmund Freud, Arnold Schönberg, Karl Kraus, Adolf Loos, Ernst Mach and the Vienna Circle – Ludwig Wittgenstein and others – were highly elaborated and resistant to the prevailing prejudices of Vienna’s conservative society and culture, with all its double moralities and hypocrisy. This is why the strong ideas, inventions and innovations of fin-de-siècle Vienna have been sustainable as well as successful all over the world. When you are sophisticated enough to survive in Vienna without losing your individuality, you can easily survive anywhere.

Alfred Weidinger

We need to go back a little in time to when Klimt was a student at the Kunstgewerbeschule – the Vienna school of arts and crafts – along with his younger brother Ernst, as well as Franz Matsch. Here, he trained initially to be a teacher of drawing and painting, and then later as an artist. They were all very poor at the time, but their painting professor Ferdinand Julius Laufberger managed to arrange commissions for them, as well as introduce them to the art market. In 1884 they decided to found a company of artists. This Künstlercompagnie was a very unusual idea, especially for students, but they recognised that it was the only way to survive financially. Matsch was the manager. It is worth remembering that this was the time when Vienna was almost one enormous construction site, with new buildings going up everywhere. It was the era of historicism, which drew its inspiration from copying historic styles, in particular in architecture and history painting. So the Künstlercompagnie thought: ‘Let’s get together, let’s build up a team because we are very fast, cheap, very good and not as difficult as some other famous artists around.’ Then they went to architects and asked for work, and quickly got commissions, primarily to decorate the ceilings of a number of theatres and opera houses.

Herbert Lachmayer

It is remarkable that they created art as a company. In the eighteenth century, artists at the emperor’s court, such as Mozart, Da Ponte, Salieri and Haydn, were merely symbol producers for the emperor. Shortly after, the concept of the artist changed fundamentally: now the image of the artist was dominated by the cliché of the “romantic genius” – suffering for his art. Mozart never did so. In the historicist age then, the artist was more or less reduced to a perfectionist of eclecticism through the dominance of academic painting. Against this background, Klimt and his friends established a company which combined economic thinking with a professional approach to art. Viennese artists were never ashamed of their interest in profit. The idea that an artist must be poor is a quite cynical bourgeois projection. Haydn, several decades earlier, had enormous financial success in his London years. But the bourgeois parvenu sticks to the prejudgment: an artist should always think about art, living on Luft & Liebe, which translates inadequately as ‘air & love’.

Alfred Weidinger

You have to remember that Klimt came out of the period of historicism. One of the artists who embraced the style was his role model Hans Makart, the academic history painter who had been the leading force in the artistic life of Vienna in the 1870s. The opulent, semi-public spaces of his studio were the scene of recurring rendezvous between the artist and his public. Makart is considered by many as being the first art star, referred to by contemporaries as an artist prince in the tradition of Rubens.

Herbert Lachmayer

Historicism focused on the idea of decoration because any ‘emptiness’ or lack of ornaments produced the horror vacui – the fear of the void. Therefore, every simple technical form, such as bridges, machines and even furniture in the home, was deemed to need a symbolic decoration in neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, neo-Baroque or neo-Rococo style. The rare exceptions were bathroom fittings, which became one of the first elements of modern design in bourgeois apartments. Otto Wagner’s revolutionary question was: ‘Should I change my clothes to a ‘knight’s armour’ to have lunch in my neo-Gothic saloon after a game of tennis?’ His philosophy followed the idea of ‘comfort’ – but not luxury – as a real necessity for life. Therefore, he strictly reduced the ‘ornamental obligation’ by using naked lamps instead of crystal chandeliers. Adolf Loos went one step further when he proclaimed that ‘ornament is crime’. With such ideas Wagner, Loos and the Wiener Werkstätte challenged the conventional taste of Viennese society generally with the indulgent consequence of their modern intelligent taste.

Alfred Weidinger

The Künstlercompagnie received offers to work for theatres, as well as rich private clients, to decorate the ceilings. In the first years they didn’t do it very well – it was really just decoration. Some of the early examples are not signed. When I went into those houses during the time I was researching the Klimt catalogue raisonné, the people I visited were surprised that the art they owned was by Klimt. Fellner und Helmer were the first architects to give them a contract, and it was not just for projects in Vienna. For example, they were employed to decorate King Carol of Romania’s Peles Castle in Sinaia. I went to Romania and found the artworks that they did there. They worked together, but also did some separate pieces. Klimt, for example, produced a frieze fifteen metres long for the music room. He painted it very quickly in Vienna, then made a crate and sent it to Romania. The king and the architect subsequently changed their plans, so they cut it into several pieces and used it in the theatre hall. It wasn’t seen as a piece of high art, but a piece of decoration.

Herbert Lachmayer

The use of historical quotations in historicism was not ironical. The historicist mentality was based on the rather naive idea that the original spirit of the idealised epochs would appear through the act of quoting – they believed in the magic of aesthetic reanimation of the admired former epoch by borrowing its decoration and style. Therefore, the city hall should resemble Antwerp or Brussels in neo-Gothic style; the university should be designed like a Renaissance building, or the villa of a successful entrepreneur should look like a neo-Baroque palace. The cynical historicism of Postmodernism in our times is different: it refuses the reference to the ‘spiritual subjectivity’ of those epochs which are ornamentally quoted. Back to the nineteenth century: Otto Wagner started as an architect by helping Hans Makart to realise an historicist festive procession. He absorbed all this historicism for many years, but was then able to establish his very new ideas of modernity in a consistent form which was definitely sustainable and could not be destroyed by Viennese odium and its armed intrigues. He is a very good example of the consequence of the implosive avant-garde of fin-de-siècle Vienna.

Alfred Weidinger

The Künstlercompagnie lasted for about fifteen years, which is a long time. However, over a matter of months in 1892 both Klimt’s brother Ernst and his father died, and he became very depressed. The Künstlercompagnie disintegrated. Matsch went off to marry a rich woman and Klimt was left more or less alone without any money. Then, as his depression was lifting almost five years later, he met someone who would change the path of his life. Carl Moll realised that Klimt had the potential to be a great artist and knew he should promote him. This is interesting because normally when you look at Klimt’s early works you can’t really identify this talent except in some details, and only then if you know him very well. Moll had the idea of founding an artists’ group which became the Wiener Sezession (Vienna Secession). They set it up a bit like a company with Klimt as the artist director and Moll as the managing director – the sort of system you might find in a museum today. It was a new model at the time, but a good one because Klimt had no idea about money. (When he died, even though he was the most successful artist of his period, he was broke.)

Herbert Lachmayer

The idea of the Secession was to use avant-gardism as a product. It was similar to the Deutscher Werkbund in Germany, but concentrated on craftsmanship rather than forging links with industry. Even the Wiener Werkstätte had been a private club with an exclusive audience – we should not forget that it had only about 60 clients.

Alfred Weidinger

It was also close to the Arts and Crafts Movement in England…

Herbert Lachmayer

Though, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Arts and Crafts Movement were not so interested in industrial production as the Deutscher Werkbund. In Great Britain as well as in Vienna the idea of exquisite ‘intelligent taste’ went hand in hand with a progressive philosophy encouraging better everyday life. This sophisticated approach focused on creating elegance by balancing the whole complexity of details – for example, Otto Wagner was experienced in every craft technique, including glassware, furniture and carpets. Back to Klimt: the painter Carl Moll recognised the extraordinary talent of Klimt and became more and more a sort of public relations manager for him.

Alfred Weidinger

Contrary to what people think and what has been written about the Secession, it was not a museum, but a gallery operation that generated cash. The artists had families and needed the money.

Herbert Lachmayer

The cleverness of Moll was that he knew what Klimt’s main attractions were. Klimt was an erotic magician who realised a certain libidinous tension between himself as professional voyeur and his naked female models. Moll constructed the Klimt image by styling the ‘genius’ and the presentation of his products/paintings. As a result a sort of Klimtomania emerged in the circles of progressive, mostly Jewish grande bourgeoisie in Vienna – it was fancy and excitingly fashionable that the lady of the house had been painted during a modelling session with the maestro in his atelier. Even the husband of the lady may have profited from the glamour of this event.

Gustav Klimt

Portrait of Eugenia Primavesi c.1913–14

Private collection

Alfred Weidinger

Moll not only recognised this part of Klimt’s personality. Being an artist himself, he could see that Klimt was a very good painter. It is worth going back a bit. The Pre-Raphaelite artists, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, were a big influence on Klimt’s brother Ernst. When Ernst died Klimt finished his brother’s Pre-Raphaelite-inspired work. During his long depression he became very interested in these artists, and then painted what is for me the most important picture he did at this time – Portrait of Sonja Knips from 1898. Moll saw this Pre-Raphaelite influence and how Klimt could work with it to create a very particular Viennese art.

Herbert Lachmayer

Yes, it is important to know that Viennese artists were able to avoid copying the melancholy of the Pre-Raphaelites because of their sense of irony and ambiguity. Depression was the most feared danger for a creative artist – ironical melancholy was the Viennese solution. In Klimt’s case, he transformed the rather boring aspects of the Pre-Raphaelites and injected ‘pornosophic fantasies’ into his work. By pornosophic, I mean the way in which he presented his idea of erotic obsession as a life-long fetishistic love for the porno-details of the female body. Like Egon Schiele, he has been stigmatised as a pornographic artist, but in my understanding his erotic obsession was a pornosophia, just as philosophy is defined as a ‘love for wisdom’. Using the term ‘pornographic’ regarding Klimt’s oeuvre reveals the petit bourgeois mentality of the person using it. He was a master of voyeuristic erotic stimulation and therefore produced his pornosophic fantasies in the head of the client – maybe encouraging him in an elegant way to have better sex at least. Even the way Klimt dressed was part of a ‘staging’ of stimulation. In his studio he wore a long working dress – resembling a Moroccan jellaba – but he was completely naked underneath. He was a highly auto-erotic exhibitionist, using the ritual of professional distance from the model as a tool of auto-stimulating his erotic fantasies.

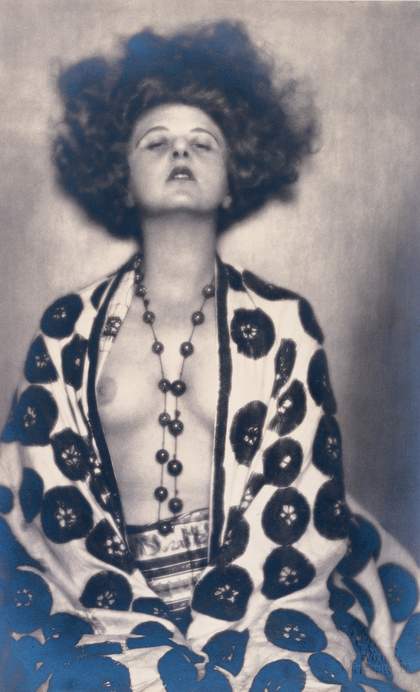

Anonymous photograph of a dancer taken at the studio of Madame d’Ora (Dora Philippine Kallmus) in Vienna 1923

Gelatin silver print

© Ullstein bild – IMAGNO

Alfred Weidinger

We must not forget that Klimt had been used to working with nude models for a long time. Not only at art school, where they did nude studies every day, but also with his colleagues at the Künstlercompagnie. So he had fifteen or twenty years’ practice, and was fully sensitised to the female body and spirit. For me, it was very interesting to realise, in doing my research, that whereas most of the female figures featured in the Künstlercompagnie ceilings are clothed, in the studies they are all nude. You will not find many drawings where the models are dressed. He had to know what happened with the body, and then he dressed it.

Herbert Lachmayer

So Klimt’s artistic production was almost like a drug – painting the nude increased the voyeuristic appeal.

Alfred Weidinger

In this respect the Beethoven Frieze became his masterwork, because it was the fulfillment of everything that he wanted to do at this time in 1902. The 14th Vienna Secessionist exhibition was designed to celebrate the life and philosophy of Beethoven with the theme based on Richard Wagner’s interpretation of the 9th Symphony, and each Secession artist contributed to it. Klimt’s idea was to do a 30ft fresco. You have to wonder why was he doing a fresco – and with such huge dimensions? It was unheard of to be creating such a piece in Europe, for a show that was going to be on for only two months.

Herbert Lachmayer

It was like a Hollywood production…

Alfred Weidinger

Or like a show in Las Vegas. It really was a grand act. In the frieze Klimt knew he could more or less fulfil his wishes. He had the power to do something on this scale, and Moll gave him that power. The Beethoven Frieze didn’t cause a scandal, though. Of course there were always art critics who wrote bad reviews of Klimt, but there were some who wrote good ones. He and the Secession artists knew they needed a reason to put images of nude women on the wall, and in Beethoven they found it.

Herbert Lachmayer

The attraction of nudity was even combined with the ‘real truth’. Let’s remember the sculpture of Beethoven [by Max Klinger] as a monument to the ‘genius’ – the composer is sitting naked like somebody in a hospital, with just drapery between his legs.

Alfred Weidinger

Yes. And very few people grasped this at the time. They came to the exhibition without knowing or understanding the Beethoven connection. Of course, there were names and titles on the walls, but then the images of floating genii and suffering humanities, the themes of hostile forces, lasciviousness, wantonness, intemperance, poetry and the arts, and a choir of angels, were all used as metaphors for Beethoven’s thinking.

Herbert Lachmayer

Klimt dealt with pathos in a different way to the Pre-Raphaelites – this use of ironic ambiguity is a Wiener Spezialität as well. Remember Goethe’s book The Sorrows of Young Werther, a semi-autobiographical work in which Werther commits suicide because of unrequited love for another man’s wife. Compared with Germany’s pathos, in Vienna no one would have committed suicide after reading Werther, because everyone felt that lost love was no reason to kill yourself. Vienna’s answer to Goethe was the bantering style of the booklet The Sorrows of Young Fanny.

Alfred Weidinger

Another difference is that Klimt uses all kinds of women in his frieze – young girls, old girls, awful women, beautiful women, fat women, thin women. The whole world of women is in the Beethoven Frieze. There are also a lot of penises in the painting, which, because of the distance from the floor level, many people miss. I was there a few weeks ago because we had to do some restoration work and when you are level with it, there they are – lots of penises. He painted them as ornament, but this was also a very brave and risky thing to do. He was gambling with the visitors – he was having fun with them. It is important to know that side of him.

Herbert Lachmayer

In this respect he was a professional voyeur and knew, of course, what unconscious effects his images would evoke in the minds of his male audience. Klimt had his own erotic theatre in his studio at home.

Alfred Weidinger

Many people who write about Klimt say he was a very intellectual guy; that he knew every book written by Sigmund Freud, every book by Otto Weininger, and so on. No. Klimt went to the coffee shop with Moll and other friends, including Gustav Mahler, and they talked. Klimt would have thought ‘I should make the frieze in the Secession’ and asked his friends: ‘What do you think? What could I do? There should be a relation with Beethoven. Do you have any ideas?’ I am very sure Mahler told him one thing, Carl Moll another. So the decision was a collective result. It was not his idea alone, you know, it was a process. And while they were there in the coffee shop, they would see a very nice girl and talk about her…

Herbert Lachmayer

Yes, and he, so to speak, seduced this girl to go along with him to the atelier and become one of his models.

Alfred Weidinger

Yes, he would think: wow, she has a nice body, so this could be the right girl for the nice nude in the centre part of the Beethoven Frieze.

Herbert Lachmayer

Klimt’s highly elaborated as well as sophisticated erotic obsessions needed never ending resources. This very deep insight was a result of his heavy depression. For a creative person such as Klimt, depression was the worst that could happen to him. For five years he lived in a hell – real not metaphorical. And then he re-created himself by bringing this hell back ‘with him’ to reality – the reality of producing art as a painter. So he became more himself as a result. He knew and understood the ‘cold hotness’ of hell. Viennese people are highly interested in the depression of others – there is a wide field of teasing conversation giving good advice on how to deal with it. Karl Kraus spoke about ‘Die Schweißhand der Nächstenliebe’ – ‘the sweaty hand of charity and pity’. We should not forget that all these psychic deviances were discussed by a manageable circle of friends and colleagues.

Alfred Weidinger

And it was quite a small audience too. The Secession, for example, had maybe only 30 collectors, so Klimt and his colleagues knew them all.

Herbert Lachmayer

Yes indeed. The husband of the lady about whom I spoke before, as a client of Klimt, would think: ‘I want that Klimt puts his professional eye on my wife.’ And so Klimt would bring out the lady’s erotic energies through his painting. And the client would feel good and think: ‘I am modern in this way, I am not an average stupid husband who gets jealous about this.’

Alfred Weidinger

Klimt brought out their sexuality, their eroticism.

Herbert Lachmayer

Step by step…

Gustav Klimt

Portait of Mäda Primavesi c.1913

Oil on canvas

150 x 110 cm

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of André and Clare Martens in memory of her mother, Jenny Pulitzer Steiner, 1964

© Image 1986 The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Alfred Weidinger

When Klimt received a commission for a painting such as the one that became the Mäda Primavesi portrait 1912, he started to sketch the woman nude. It didn’t matter if it was a young girl, or an old woman. And when he did a nude body, he did it complete – not a silhouette or an outline. Once he had done that, then he painted the clothed body. This is the reason there is an eroticism in his pictures – the sexuality comes out of the painting and you can feel it. When you see, say, Emilie Flöge’s portrait 1902, it’s the same.

Herbert Lachmayer

He probably had a special ‘mental orgasm’ while producing his paintings – not ‘beside’ his act of artistic productivity, much more as a stimulus for the same. Sublimation might have been very sensual for him. This was the erotic hype of this time. Everyone wanted to have voyeuristic fantasies watching naked females – but this was the amateur approach of voyeurism. Klimt was the maestro of voyeurism. He was an extremely good draughtsman – a genius of drawing. Think about Pierre Klossowski and his ‘sexual act’ of drawing.

Alfred Weidinger

So he did this in a very simple way. Klimt was not that intelligent, you know.

Herbert Lachmayer

No, he was not an intellectual.

Alfred Weidinger

We cannot say he was influenced by Freud or by Weininger, because he had no idea what was going on. They talked in the coffee shop about Freud, of course, and you could use Freud’s and Weininger’s analysis to interpret his paintings, but they did not influence how he made them.

Herbert Lachmayer

No, because he didn’t need to be inspired by intellectual discourse.

Alfred Weidinger

He needed himself.

Herbert Lachmayer

But he also absorbed influences, because he was very, very open-minded and sensitive to what was going on around him.

Alfred Weidinger

As well as the Beethoven Frieze it is worth mentioning the Stoclet Frieze, which is also a masterpiece. There is a difference between the two. The Beethoven Frieze was a masterwork because he did everything that he wanted to do. He was the client. The Stoclet Frieze was for a private client and made for a dining room, so he could not use nude women. However, he could fulfil everything that he would like to do with his materials, and he used gold, porcelain, silver, enamel and precious stones.

Herbert Lachmayer

Yes, but the eroticism was bound to be the focus of material obsession: we can admire the material fetishism in his work…

Alfred Weidinger

The title of the frieze is The Fulfilment – which was exactly what it meant to him. In this project he is almost going back to his roots, because he was trained as an applied artist. Even though it was made for a dining room, he still managed to convey the eroticism in the beautiful figure of the dancing woman in the frieze. Again, you can sense the nude body under the dress. And again, when you look at the preliminary drawings, he has drawn her as a nude figure. The masterwork in this respect is, of course, The Kiss. This is a painting about wishes.

Herbert Lachmayer

And, in this sense, he was the master.

Alfred Weidinger

Yes, he was a connoisseur. But we have also to think about when these works were made. The Kiss was painted between 1907 and 1908. The Stoclet Frieze was made between 1906 and 1911. In the photographs of Klimt at this time, he looks very lonely, and this was because he was, more or less, alone in terms of what was happening in the art world internationally. Picasso had painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Cézanne had died a year earlier. So The Kiss and the Stoclet Frieze were already deemed old fashioned art. That said, Klimt was intelligent enough to realise this. He knew that he had said everything he wanted to say, he had fulfilled his wishes in the Beethoven Frieze and, later, in The Kiss.