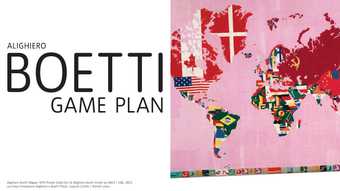

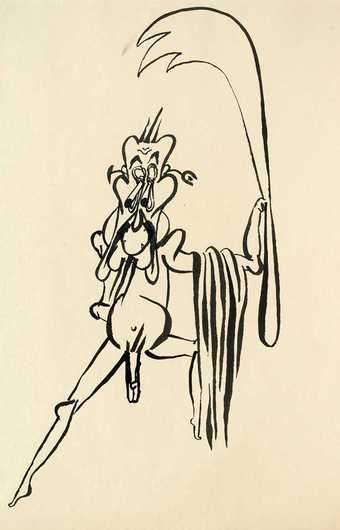

Francesco Clemente

Untitled 1972

Ink on paper

33 x 22.2cm

Photo: Tom Powel

Courtesy Deitch Projects, New York © Francesco Clemente

This is a tale of four contemporary art shamans, in a pre-9/11 world that could still entertain rosy illusions of prelapsarian time and space. A tale of stoned-soul picnics in 1970s Kabul and the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan before the Soviet invasion of 1979; of vibrant, easy-to-plunder craft traditions – embroidery, paper-making, miniaturists for hire – in Pakistan and India, before their emergence as political minefields and global giants; of long walks through the labyrinthine kasbah in Cairo, of taking tea with Paul Bowles in Tangiers, under the influence of his 1949 novel (and later Bernardo Bertolucci’s film), The Sheltering Sky.

The artists in question: Alighiero e Boetti, Sigmar Polke, Francesco Clemente and Philip Taaffe. (We won’t be speaking of Orientalism in the work of Howard Hodgkin or Brice Marden, although we could.) Boetti (1940–1994) was a pioneering member of the 1960s Arte Povera movement in Italy. Polke (born 1941) was Joseph Beuys’s funniest student at the Düsseldorf Academy in the 1960s. Clemente (born 1952) was a Neapolitan shape-shifter before he became a sought after society portraitist – the Boldini of our age. Taaffe (born 1955) first became known in the mid 1980s EastVillage for his exact appropriations of Barnett Newman and Bridget Riley – long before the thorough-going, recent exhumation of Op Art.

Beginning in about 1979, their art reconfigured, and reconfirmed, our vision of the Orient. We can’t call them Orientalists, yet each travelled to the Middle (and Far) East, and brought back textures, texts and artefacts that changed the course of contemporary art. The diverse strains of an emerging 1980s trans-avant-garde were, in fact, given strength, and even a means of auto-critique, by the then languishing notion of Orientalism, a hoary nineteenth-century construct which had just been given a kick in the pants by the appearance of Edward W. Said’s brilliant book Orientalism (1978), a series of essays by the Palestinian literary critic that spoke of the West’s cultural imperialism in no uncertain terms.

A bit of personal prehistory here: in 1979 I was a young art historian in New York, pondering a dissertation on eighteenth-century turqueries, or the Turkish influence on Rococo art, as a harbinger of nineteenth-century Romanticism (Jean-Etienne Liotard [1702–1789], the Swiss-born, self-styled peintre turc, was to be my main man). I remember being fascinated at the time that the contemporary dealer Heiner Friedrich and his wife Philippa de Menil (recent founders of the Lone Star Foundation, soon to be the Dia Art Foundation) had taken up with the Sufi dervishes from Konya, Turkey, brought them to New York, converted a slick loft space in SoHo into a temporary mosque and even made their East Side townhouse into a contemporary turquerie, complete with Dan Flavin fluorescent installations, Persian carpets and low-lying sofas. I remember visiting the house, attending several concerts of the dervishes uptown and down (they were quite a sensation in the avant-garde circles of New York art, music and dance) and thinking this would make a great postscript to my dissertation. (I could have never dreamed that one of my artists, the little-known Antoine Ignace Melling [1763–1831], who lived and worked in Istanbul, would become a key influence on the young Orhan Pamuk, as described and profusely illustrated in his book Istanbul: Memories and a City of 2005.)

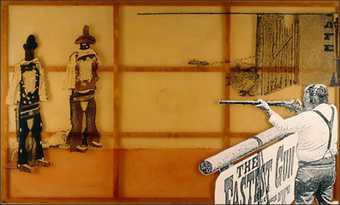

Sigmar Polke

Treehouse 1976

Mixed painting techniques on paper

205 x 298 cm

Private collection, Hamburg © Sigmar Polke

It was just about this time that Sigmar Polke’s crazy paintings on printed fabric – some of them kitschy, Egyptoid patterns – were first being seen in New York, at the Holly Solomon gallery, that bastion of the Pattern and Decoration movement, a short-lived phenomenon which found its own justification in the Orientalist aspect of Henri Matisse’s art. In 1977 the mythic Blinky Palermo, Polke’s friend who showed at Heiner Friedrich, died mysteriously in the Maldives, like a latter-day Sir David Wilkie. Palermo’s show To the People of New York City at Friedrich’s opened posthumously that year, and he would become a cult presence for young artists, for example Julian Schnabel, who named an early painting after him.

Also in these years, a strange and guru-like young Italian named Francesco Clemente and his beautiful wife Alba were just arriving in Manhattan from India via San Francisco. I met them through the writer Edit deAk, who wrote the first great article on Clemente, ‘A Chameleon in a State of Grace’, in Artforum, back when they all spoke a unique form of broken English. Clemente’s first shows of portable frescoes and Indian miniatures at Sperone Westwater were soon to shake up my New Yorker’s view of things. Alighiero e Boetti I thought of at the time mainly as an Italian Conceptualist – I saw his early shows at John Weber, but didn’t really get them. Their Afghani component became clear to me only in the mid 1980s, and the full splendour of his series of carpets only in the consummate, multi-culti grab-bag exhibition, Les Magiciens de la Terre, at the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1989.

Sigmar Polke

The Bear Fight 1974

65 x 84 cm

Photo: Uwe H. Seyl

Courtesy Froehlich Collection, Stuttgart © Sigmar Polke

Philip Taaffe was as yet an artist in formation in 1979 – a reclusive type, living at a seminary in West Chelsea (long before its contemporary art heyday), and poring through books on architecture and decorative arts in the nearby Fashion Institute of Technology library where he had a day job, and where I occasionally went to research Turkish costumes.

David Seidner

Philip Taaffe’s New York studio 1993

Photograph

© International Center of Photography, David Seidner archive

In 1968 Alighiero Boetti added an ‘and’ in Italian to his name, thereby creating the possibility of dual artistic identities. For many years he produced embroidered maps and text works in Afghanistan in collaboration with local craftswomen, and even bought a hostel in the late 1960s in Kabul named the One Hotel. (An exterior photograph makes it look like an Ed Ruscha documentary shot of some anonymous building on the Sunset Strip in LA.) After the Soviet invasion, Boetti switched his tapestry production to Peshawar, Pakistan – just as the invasion of Afghanistan was coming on the Western evening news. (Flash forward to Mike Nichols’s comic, true-story movie Charlie Wilson’s War of 2007, with its costume-drama footage of the refugee camps in Peshawar – all of it filmed in Morocco.)

Today Boetti’s embroidered maps from the 1970s and 1980s literally chart world powers, such as the Soviet Union, that no longer exist. His embroidered verbal sayings – such as ‘to leave certainty for uncertainty’, ‘the endless possibility of existing’, ‘the less you say the better is’ – more than ever have a runic, laid-back grace. His larger embroidered word pieces, for example Tapestry of the Thousand Longest Rivers in the World 1976–82, with its dense field of river names and numerical lengths, exude the Conceptual charm of all such rigid topographical systems that are riddled with inaccuracy and doubt – a reflection of all forms of knowledge, including Orientalism.

Konrad Lueg, Sigmar Polke, Blinky Palermo and Gerhard Richter in front of Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Cologne 1967

Courtesy collection of Dorothee and Konrad Fische

The same age as Boetti, Sigmar Polke hailed from Silesia, then in the eastern part of war-torn Germany (now part of Poland). He quickly became the most subversive of the German Pop painters. In the early 1970s he took to the road, snapping photographs of gay bars in Brazil, bear fights and opium smokers in Afghanistan and later photographing in south-east Asia and Australia. He developed these shots in a secretive and prolix studio practice in Cologne. The bear fight and opium den works today resemble nineteenth-century photographic experiments: the subjects are stock Orientalist types; only one isolated figure in a bear fight scene makes direct eye contact with us, thereby challenging the Orientalist gaze. It’s the hand-colouring and the painterly manipulation of photo-emulsions that now look most eccentrically trippy. (I remember seeing a 1982 show of his Australian photos in Paris in which the sloppy-looking large prints were exhibited horizontally, framed under glass, on the floor; even at the time, this seemed the work of a stoner.)

Polke’s ongoing alchemistic abstractions, often using unstable and even poisonous paint substances, and his history-based figurative works bubble up as some of our most influential contemporary Orientalist artefacts. I will never forget History of Everything, his big show at Tate Modern in 2003, in which gallery after gallery of encyclopedic, caustic paintings brilliantly cross-bred images of Texas gun culture with blow-ups of post-9/11 German newspaper illustrations, including The Hunt for the Taliban and Al Qaeda – rendered as a colossal, grisailled machine painting on fabric.

Francesco Clemente was essentially discovered, while still a student in Rome, in 1972 by Boetti. Clemente travelled with Boetti to Afghanistan in 1974. The poet Rene Ricard writes in his indispensable chronology in the catalogue for the 2000 Clemente retrospective at the Bilbao Guggenheim: ‘There, they travelled by truck on the old silk road up to Pamir and the Hindu Kush on the Chinese border. They reach Feizabad, the meeting point of all the nomadic tribes. Today, it no longer exists… Clemente doesnot draw in Afghanistan.’ In a picture of them by a street photographer (‘on the final day of their travels,’ the caption reads), the 22-year-old protégé is very tanned, sprouts Rasta hair and looks mega-stoned; while the elder, dandified magus stands next to him like a proud Mephistophelian older brother, cigarette in hand.

Clemente lived for long stretches in India in the mid to late 1970s, imbibing esoteric knowledge at the occult library of the Theosophical Society in Madras, thereby making direct contact with the nineteenth-century Orientalist culture of Madame Blavatsky and Annie Besant, and listening to daily lectures by the then-ancient J Krishnamurti. Recently, with the art-historical re-excavation of the 1970s, we have begun to learn even more about his early work. In a New York show at Deitch Projects in 2007, Clemente displayed for the first time 1970s drawings and photocollages from Rome, Srinagar, Madras and Delhi; these were a revelation to those of us wishing to understand his formation. There we saw a collage of photos of his ceiling fan in Srinagar; a strange political doodle depicting a crocodile bearing a blue globe covered with stars on its back; and another proto-Keith Haring cartoon with four images – a figure with gas mask and headphones, a surveillance close-up, a pistol and a phallus and an aerial shot of people being blown to bits.

Clemente later made several unforgettable series in collaboration with Indian craftsmen. The best is Francesco Clemente Pinxit 1980–1, 24 miniatures done by fifteen boys, aged eight to twelve, each with his own specialised motif, after the artist’s drawings. Thus were issues of Western authorship effectively shot to hell in the early 1980s. Clemente has since emerged as one of our most trenchant self-portraitists (some of his most recent works are direct lifts of Kalighat painting); and a measure of his fame, not to mention his Orientalist clout, is the catalogue of his 2005 show at Gagosian in London of self-portraits, with its brief history of Western portraiture by Salman Rushdie. Our fourth man, Taaffe, was born in New Jersey and came of age in Manhattan in the East Village scene of the early 1980s, where he was early on allied with the Appropriation art movement. In 1988 he left New York and decamped to Naples, where he operated from the grandiose Villa Pierce (a seaside wreck in Posillipo once visited by Winston Churchill). During these years, Taaffe travelled to Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco and then back in Naples, making the grisaille abstraction Al Quasbah 1991 as well as the Rothko-inspired Old Cairo 1989. He also made an artist’s book, Chocolate Creams and Dollars 1992, with Paul Bowles’s companion, Mohammed Mrabet. Taaffe used as illustrations old photographs he bought and also photos he took in Morocco.

Upon his return to New York in 1991, he found and converted, back to its Neo-Gothic bones, an immense former Afghani schoolhouse in the midst of the Garment District in mid-town Manhattan, which he gradually transformed into a latter-day Orientalist’s atelier. One great work from that time, Passionale per Circulum Anni 1993–4, has big spiralling black forms that look inspired by Celtic interlace as well as by Neapolitan metalwork, but may in retrospect have also been inspired by the mosaics at the Omayyad mosque in Damascus, which Taaffe visited on a quick trip in 1993.

In his Lord Leightonesque atelier (not to mention his Orientalist digs that once belonged to Virgil Thomson in the Chelsea Hotel), Taaffe produces sublime, minutely crafted field paintings. Post-2000 he has gradually incorporated more and more of the marbling technique he laboriously taught himself, using a variety of manuals, including that of the Turkish marbler Nedim Sönmez. He continues to compile found images, most recently silk-screened heads from photos of sculpture culled from central Asian, north-west coast Pacific and Celtic cultures, among them images of Gandharan heads with an Afghani provenance. Works such as Cape Sinope 2007 are imaginary travel paintings made with the artist’s proudly antiquated, painstaking attempts at precision and accuracy of orchestration. These are world-affirming totems of reconciliation, very much in tune with the positivist, exploratory zeal of the nineteenth-century Orientalists.