Some mornings in St Ives, in 1948 and 1949, after our respective stints of waiting at the breakfast tables of holiday-makers, Terry Frost and I would meet at his studio to talk and look at work in progress. To get there we would walk along Back Road West, almost to the end where Alfred Wallis’s cottage was. On the right were Porthmeor Studios and up the steps was Willie’s (Wilhelmina Barns-Graham’s) studio, with its great windows overlooking the curve of Porthmeor Beach. But there we would turn right and walk down a ramp of smooth granite blocks to two doors at the far end – one of which opened into Terry’s studio and the other into Ben Nicholson’s (later Patrick Heron’s).

The wall between Terry’s studio and Ben’s was so thin we could hear sounds through it. We could hear Ben moving around with that prancing step of his, somewhat between walking and dancing. We could hear him switch on the little radio he kept on an old orange box, or wind the handle of his gramophone and put on a New Orleans jazz record, and Jelly Roll Morton would strike up the beat. And we could hear Ben begin to scrape at the surface of his paintings with a razor blade, scrrch-scrrch-scrrch. Then we’d hear him abruptly stop the music. And in the silence that followed we’d hear the scraping begin again, but more methodically now, and Terry and I would stop our chatter, respecting the physical presence of Ben’s concentration.

It may seem odd that an artist would begin his painting day by scraping at the surface of an old canvas, or a panel of mahogany, or a piece of cardboard, with a razor blade. I am reminded of that oft-quoted remark made by Ben’s artist mother, Mabel Pryce, who said that when people began to talk about art she would go downstairs and scrub the kitchen table. Maybe kitchen tables were part of Ben’s genetic make-up, for throughout the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s he used the top of an old kitchen table as his palette. He would mix his oil colours directly on its pine boards, and then at the end of the day he would pour out some turps and clean up the table top with rags. Never one to waste anything, he would look around for a canvas, or a board, or some sheets of cartridge paper, and he would wipe the liquid colours on to their surfaces. ‘Making a ground,’ he called it.

Ben had quite a few of these canvases leaning with their faces to the wall. At the beginning of the day he would turn one or two around and stare at them. And suddenly some characteristic would ‘speak’ to him. Maybe it was an accidental streak of vermilion in a veil of pale ivory-brown, or a flash of blue in a greyish mist of saturation, offering a sense of the sea or a swirl of wind. Then he would begin to scrape in earnest. And it always seemed to me that Ben’s scraping was related to the way the wind and the rain moulded the undulating uplands of the Penwith peninsula in south-west Cornwall.

The accent colours Ben used at the time in his paintings were usually near-primaries, cadmium yellow, cerulean blue, red oxide, magenta, sienna, black and white; and when at the end of the day he poured turps on his table and ran the colours together with a rag, they might merge into some sort of pale brown, depending on the amount of turps, or they might become a pale ivory or a translucent greyish blue; and then there might be the happenstance of a streak of bright colour that had somehow got stuck in the web of the cloth, a sharp red or yellow. On some canvases or boards there might be several layers of previous grounds, so that when Ben scraped with his razor blades he would make discoveries that would set the rhythms of his creative thought in motion. And the vocabulary of his paintings was invariably the intersecting outlines of bottles, jugs and wine glasses. But vocabulary is not language, and the language of his paintings was landscape.

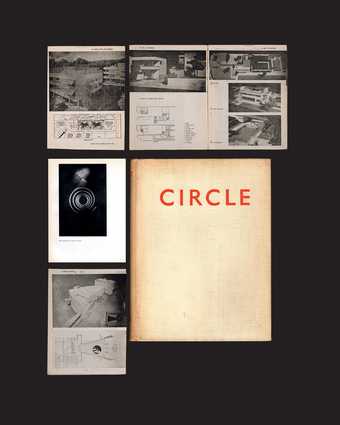

In the 1930s Ben’s white reliefs had virtually no texture to them, but I have always felt that they carried, in spite of the austerity of their vocabulary of squares and circles, the essential equilibrium of the Dales in Cumberland and the Ridings of Yorkshire – landscapes which had affected him so strongly in the decade before he came to Cornwall. As with the land, the equilibrium of these white reliefs is not static, but is continually changing with the quality of natural light as the day progresses from dawn to twilight. Were his reliefs and paintings Cubist, reflecting his 1930s friendship with Braque; or geometric, reflecting his affinity with Mondrian; or linear, reflecting his association with Gabo; or were they Modernist, reflecting the ideas in the publication he edited with Gabo and Leslie Martin – Circle: An International Survey of Constructive Art? These questions are important to art historians, but in my view they are peripheral to Nicholson’s language. For here we have art objects that reach resolutions of harmonic interrelations of line, colour, space and texture, in which allusions to the timeless rhythms of landscape and the presence of the sea are absorbed into the wholeness of the object.

Front cover and pages from Circle: An International Survey of Constructive Art 1971

Photos: Middle L and Bottom R, Polly Dufrasne

© Tate. Photo: All others, Rod Tidnam

Often in the late afternoon there would be a light tapping on Terry’s door made by the three slim gold bands that Ben wore on the final finger of his left hand; or there would be a similar tapping on the door of the little house that Willie and I lived in on Teetotal Street, and Ben, head clad in a cotton cap worn slightly on one side, would ask one of us if we’d like to say whether we thought that whatever he’d been doing in his studio that day was complete.

There we would sit, on his sofa, young and inexperienced, and say whether we thought a certain red was too strong, or a certain blue too weak, or a certain line insufficiently rotund. And Ben would ask us why we thought so, and would listen pensively, head on one side, the hairs of his eyebrows alert like the antennae of insects. Or we’d discuss the quality of his ‘grounds’, and to what degree they evoked the transitory qualities of the land and the sea all around us – the pale textures of the sea’s horizon at twilight, or the richness of deep brown soil after rain. Or we’d discuss the energy and allusions of his sharp colours – the flash of golden yellow gorse or the lucid blue of the midday sky when glimpsed through wind-tumbled clouds after a rainstorm.

More than half a century after those evenings, Terry and I reminisced about our conversations with Ben. We reflected on the aloneness that artists often feel, and on that kind of simultaneous elation and emptiness bordering on despair that comes at the end of a work; and we realised that what Ben valued was not whether a certain red or a certain blue were right, but the spirited quality of the conversation that a particular painting engendered – for only then would he know that its language was alive.