Juergen Teller on Cecil Beaton’s Miss Nancy Beaton as a Shooting Star 1928

It’s a lovely picture, like a fairy tale. It’s not necessary to know the allegorical reference, and maybe it isn’t specific to the sitter, but the photograph is really magical and the use of that foil is such a simple way to put some glitter and fantasy into it. In his early portraits Beaton often used backdrops of beautiful fabric or other material to surround the subject, and it distances them from their real selves as much as the imaginative costume. The photograph, and the sitter, is timeless, charming and innocent.

Sarah Jones

Analyst (Couch) (II) 2008

C-type lambda print mounted on aluminium

122 x 122 cm

Courtesy Maureen Paley © Sarah Jones

Sarah Jones on August Sander, Thomas Ruff and Walker Evans

I have often looked at August Sander’s work – particularly when I was doing my Actor series of photographs. I’m interested in the idea of the portrait, and how we might engage with it. In Sander’s pictures the only information about the person we are given is their trade, though there is something very direct and naturalistic about the way he presents them – almost everyone in his photographs is looking back at us. These are very composed portraits – the people are there to be scrutinised, but they resist easy categorisation. Sander’s aim was to document the individuals within a German society that was in the process of trying to destroy that individuality. As a result, they have a certain power: the images reflect the times in which they were made. In his pictures you can’t help thinking about that social relationship – about what photography could do to shape those times.

As well as Sander, I was also looking at Thomas Ruff’s work. We are clear that he has a relationship with the people in his photographs, in that we know they are his peers. The portrait is stripped back, as if it were an institutional document. We scrutinise them perhaps for differences and similarities, how each may have prepared themselves for their portrait. So in the Actor series I was testing, in a sense, what it is to make or become a photographic portrait, and the demands we as viewers might also make; how we might associate or disassociate ourselves when looking. How much do we project when we engage with a picture of someone other than ourselves? There is the potential for narrative too, though not explicit, a relationship between the two actors pictured together. Of course the work operates on two levels: factual while alluding to the imagined. At the same time I had begun work on my photographs of psychoanalysts’ rooms and couches. The images were partly based on Piero Della Francesca’s Montefeltro Altarpiece c.1472 in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, and what I saw as that painting’s relationship to the contemporary photographic portrait; to gesture, the tableau, to the use of gaze and relationship to viewer, and in particular to a flattened illusion of space and a frontality. With Actor the gestures are small, naturalistic, the photographic space is reduced, the sense of location or setting is removed, the only context is that of the pale backdrop against which the subjects are photographed in the studio (which becomes an empty space in the image) and the gallery in which the works may be hung. The scale of the figures approximates life-size; this also affects the way a viewer might relate to the portrait.

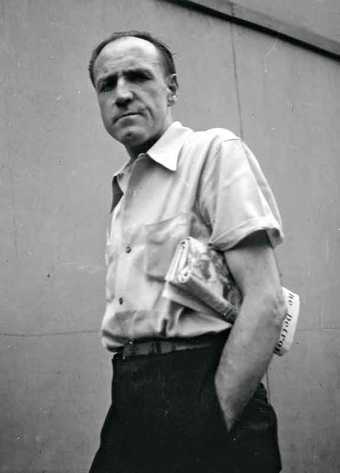

In contrast, in Walker Evans’s Labour Anonymous series of photographs, the portrait is made by the figures moving through space. The street is the studio. He shows the idea of the photograph of the moment, the Modernist idea of the belief in the individual.

Walker Evans

From the series Labor Anonymous, studies of pedestrians in Detroit, Michigan, commissioned by Fortune magazine 1946

Gelatin silver prints

16 x 11.7cm

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Walker Evans

From the series Labor Anonymous, studies of pedestrians in Detroit, Michigan, commissioned by Fortune magazine 1946

Gelatin silver prints

17.78 x 11.4 cm

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Walker Evans

From the series Labor Anonymous, studies of pedestrians in Detroit, Michigan, commissioned by Fortune magazine 1946

Gelatin silver prints

17.78 x 11.4 cm

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

David Goldblatt on Helen Levitt

In my opinion Helen Levitt is one of the truly great photographers, and I find it sad that she and her work have been so little honoured and appreciated in today’s very wide world of photography. Her work is disarmingly simple. Most of it on city streets, most of it of children as they go about their children’s business, playing, posing, exploring, interacting with each other, with adults and with life on the street. Straightforward 35mm photographs, no fancy footwork with extreme lenses and viewpoints, no arcane processes. But what photographs! Visual poems full of grace and life. Unaffected, never condescending or patronising, innocent yet knowing as children often are. Her anticipation of moments is uncanny, as though she herself is a child in the game. And yet there is no pretence of taking photographs as though a child. They are the photographs of a woman, a supremely sensitive and rare adult woman.

Helen Levitt

New York c.1940

Gelatin silver print

35.6 x 29.7 cm

Courtesy Laurence Miller Gallery, New York © Helen Levitt

Chris Killip on Boris Mikhailov’s Case History 1999

A week after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I was in London at a dinner party where many of the guests were captains of industry, and their excitement over recent events was palpable. The most memorable quote of the evening was: “This news puts us on a par with the USA, it’s going to be just like having Mexico on our doorstep.”

Boris Mikhailov blatantly and insistently shows us the shocking consequences (for some) of the collapse of Communism in his photographs from Case History. Personally, I rather wish I had never seen this work, so that I could pretend that these images didn’t exist – that Mikhailov hadn’t made them and that I was not implicated in them. Unfortunately, I now have him to thank for these indelible imprints on my brain, like postcards from the vanquished to the victor. Obviously, he sent them to help us to celebrate more wholeheartedly the spoils of victory from our recent economic war.

I was shocked when I first saw this work, and shocked when I returned to ponder on these slyly referential, snapshot-like photographs, now blown up on the gallery wall. Boris, how apt. This compelling work cannot help but raise the question: what is a photograph and what is its purpose?

The self-congratulatory smugness of most photographic offerings has lulled me into a very low level of expectation. The bulk of photographic work produced for galleries, produced for Hollywood, produced for the art scene is geared to an audience. It is self-censored, and its reception (such a strong American concern) is second guessed. No wonder that most of current photography is so devoid of content. I mean, perfectly seriously, who is going to buy Mikhailov’s work? Masterpiece it might be, but who wants to be reminded so forcefully by content that actions always have consequences?