Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Detail of Sketch of a Bison c.1912–13

Drawing on paper

21.6 x 34.3 cm

© Tate. Photo: Joanna Fernandes

Pae White on Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Sketch of a Bison c.1912–13

Focusing on specific parts of an animal’s anatomy is something I often do. At times I fetishise my dog’s ears, at other times her neck. Lately I am drawn to her paws and legs. Who knows (other than a true dog owner) what causes this fleeting fascination? A benign lust that is also a form of awe and respect for something so perfectly designed, yet so alien and magnificent, and (happily) so accessible to me? This is why I focused on the specific area in the sketch: the luscious grouping of the delicately rendered limbs.

Though Henri Gaudier-Brzeska may be well-known in Europe, I was unfamiliar with his work. I was amazed to learn that not only does Tate own 62 of his pieces, but that he was an artist who made work for about only four years before dying in battle at the age of 24 in 1915. I was drawn especially to the numerous sketches of zoo animals, both in terms of quantity and quality, and can only imagine how they might look when installed together. However, it is the undercurrent of melancholy that captures me, a quiet sadness reflecting his incredibly brief career as well as his haiku-like drawings and how each, very simply, mirrors the other.

The manner in which this bison is rendered is like a breath – open and empty. In fact, it probably took not much longer than a single exhale to sketch. What I find most curious is the ghosting of another animal in the background. Although this must be on the recto side of the sketch, it seems to be embedded in the page, or even in a state of dissolve. The form and state of this mysterious creature is completely ambiguous. Somehow I read it as the soul of the bison departing.

Sketch of a Bison was presented by C. Frank Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society in 1930.

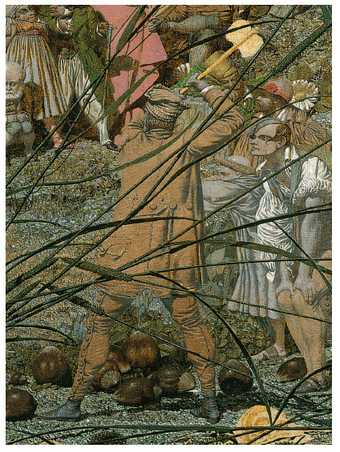

Richard Dadd

The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke (detail) 1855–64

Oil on canvas

54 x 39.4 cm

© Tate. Photo: Rod Tidnam, Tate Photography

Peter Schjeldahl on Richard Dadd’s The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke 1855–64

Richard Dadd’s pictures are illustrational, in the Victorian vein, but the best of them – notably a talismanic little item, The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke – are also as dense and worrisome as uranium. Viewed voyeuristically through tangled timothy grasses in a darkling grey-green underbrush, the tiny woodsman Feller prepares to axe a hazelnut. Grey-fleshed royals and commoners of a miniscule realm, attended by somewhat lugubrious fairies and a brass band, watch with impassive approval. One needn’t be a vulgar Freudian to square this business of busting nuts with Dadd’s parricidal rap sheet. Diagnostic readings of art are boring, though, and The Fairy Feller does not bore. Looking at it can be a euphoric ordeal.

You keep wanting to turn the lights up. I suppose that Dadd had moonlight in mind, but the leaden illumination hints at something rarer, maybe a solar eclipse. Details we don’t care about, such as some daisies, glow lividly, while significant figures founder in murk. The difficulty of seeing feels symbolic of a deeper malaise: a difficulty of being. The Feller is set to strike. It is okay for him to strike. The sinisterly glamorous moment tingles with held-breath tension. Nothing happens. The painting is not pretty. Dadd’s nine years of labour on it left a surface untempting to the touch. His fairies are plainly the spawn less of air than of soil: Calibanettes. But the work’s very grotesquerie guarantees its appeal to contemporary sensibilities. It bespeaks invisible things that someone needed very badly to make visible.

The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke was presented by Siegfried Sassoon in 1963 in memory of his friend and fellow officer Julian Dadd, a great-nephew of the artist, and of his two brothers who gave their lives in the First World War. It is on display at Tate Britain.

Jacob Epstein

Jacob and the Angel 1940–1

Alabaster

214 x 110 x 92 cm

© The Estate of Sir Jacob Epstein. Photo: © Tate

Vincent Katz on Jacob Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel 1940–1

Riser

Mother crushes son

With love

The seriousness

Of her embrace

Son almost crying

From feeling that

Returning see it’s

Not at all embrace

Unless embrace

Be a kind of fighting

Ancient story

Of struggle

Between here

And hereafter

Future you do

Or do not believe

A personal and

Social history

But also this

Great surging feeling

Of a parent’s

Overwhelming love

October 12, 2007 [Revised April 29, 2008]

Jacob and the Angel was purchased with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund,The Art Fund and the Henry Moore Foundation in 1996.

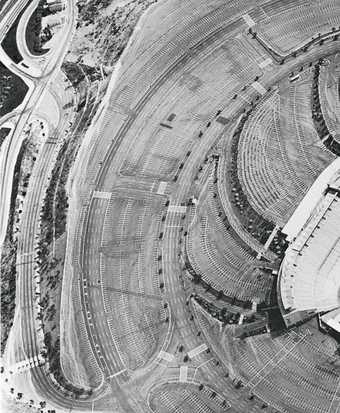

Ed Ruscha

Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles1967

Detail of Dodgers Stadium, 1000 Elysian Park Ave

One of 30 gelatin silver prints

9.4 x 39.4 cm

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery © the artist

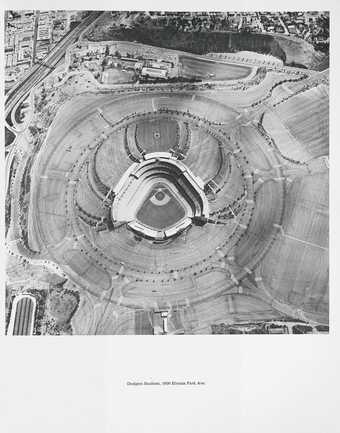

Ed Ruscha

Thirty-four Parking Lots in Los Angeles 1967

Detail of Dodgers Stadium, 1000 Elysian Park Ave

One of 30 gelatin silver prints

9.4 x 39.4 cm

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery © the artist

Mary Richards on Ed Ruscha’s Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles 1967

One Sunday morning in 1967, Ed Ruscha hired a helicopter and a commercial photographer, Art Alanis, and the pair flew over Los Angeles to photograph the city’s parking lots as they lay vacant. These dramatic aerial views provided the raw material for Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles, one of seventeen artist’s books he would publish during the 1960s and 1970s under his own imprint. “I want to be the Henry Ford of book making,” Ruscha said.

Myriad rings of parking spaces circle the 56,000-seater Dodgers Stadium, 1000 Elysian Park Ave. Cars, in theory the organising principle of the book, are notable by their absence. Instead we are left to view the abstract patterns of the grid devised to accommodate them. In precisely captioned shots of drive-in theatres, film studios, air terminals and office complexes, the city’s infrastructure is laid bare; it’s a sprawling city with no centre, where a car is essential to navigate the terrain. Ruscha says about arriving from Oklahoma in 1956: “The first thing that hit me was the number of people that were coming here. In the late 1950s there were something like 1,000 people a day… bringing in 750 cars every day. I was overwhelmed by that, and also by the smog.” The serial images of vacant lots also suggest a ghostly emptiness, the Los Angeles of science fiction and film noir. Or, as J G Ballard put it: “Ruscha’s images are mementos of the human race taken back with them by visitors from another planet.”

Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles is available to view in Tate Library by appointment.