Eric Fernie

In the introduction to Neuroarthistory: From Aristotle and Pliny to Baxandall and Zeki you write that neuroarthistory is not a theory, but an approach; its defining feature is a readiness to use neuroscientific knowledge to answer any of the questions that an art historian may wish to ask. Would you like to expand on that?

John Onians

Art historians have always known that both the making and the experiencing of art rely on the brain, but they rarely ask themselves how the brain works. A neuroarthistorian is someone who does. Neuroarthistorians exploit all the tools used by other art historians, but they also use an additional tool, neuroscience, to help them to understand all aspects of the making and viewing processes. Today there is so much new knowledge in this field that our understanding of art can be transformed.

Eric Fernie

What new knowledge are you referring to?

John Onians

One set of knowledge relates to the overall structure of the brain, the functions of its different areas and how they relate to each other. Such knowledge applies to virtually everyone, and can be used to study inborn preferences that are almost universal. Another set relates to the way the brain of each individual develops differently, principally because of what is known as neural plasticity.

Eric Fernie

That sounds intriguing. What is it?

John Onians

The basic idea of neural plasticity is that connections between the nerve cells or neurons in our brains are liable to form or fall away in response to our changing experiences. Because each of us has had different experiences, we each have differently configured neural networks, and, as a result, we all have different abilities and inclinations.

Eric Fernie

What is the importance of that for an art historian?

John Onians

For example, if we look with attention at a particular object, the visual networks involved will be strengthened, thereby giving us a preference for looking at objects that share the same properties. This means that the more we know what an individual has been looking at, whether it is a man-made object or a landscape element, flora or fauna, the more we will be aware of what unconscious preferences may have influenced any art-related activity in which they may have been involved. This allows us to reconstruct aspects of the mind of makers, patrons and viewers of which we were previously ignorant.

Eric Fernie

Would a neuroscientist recognise that as the application of neuroscientific knowledge to art history?

John Onians

All neuroscientists would agree about the value of using neuroscience to understand universal visual proclivities and preferences. They would see it as providing the basis for a discipline of neuroaesthetics. Not all, though, would want to give prominence to the idea of plasticity. For one thing, taking it into consideration would complicate the design of experiments. For us art historians, on the other hand, plasticity is something we very much need to understand if we are going to answer the questions we want to ask about the way preferences vary between individuals and communities. It is one of the resources that allows neuroaesthetics to become neuroarthistory.

Eric Fernie

I can see how that helps in dealing with artistic activity, but from the structure of your book you seem to want to apply the neural approach to all thinkers.

John Onians

Yes, that is I why I call the writers I discuss ‘neural subjects’. I want to bring out the fact that their intellectual identities, or ‘subjectivities’, were the result of exposure to all sorts of experiences, not just to words, as many people would have argued a decade or so ago. A conception of subjectivity based on texts can now be seen to be defective, because it excludes consideration of influences of many other kinds. It also, by emphasising the more rational life of the mind, draws attention away from other vital forms of life – the emotional and the visceral. This is the reason why I prefer to think in terms not of the mind, but of the brain. The mind is conceptually monolithic, but the brain is inherently extraordinarily complex. It is made up of one hundred billion neurons, and each of those neurons has up to one hundred thousand connections, changing in response to our experiences from nano-second to nano-second. When you think in terms of the brain, you have to be aware of a much wider range of factors affecting a person’s views. You also may end up thinking that they were more influenced by their life experiences than by books. For example, in the case of Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755), the critical factor behind his recognition of the importance of climate and ecology may have been his experience as a winegrower, and in the case of John Ruskin’s similar perceptions, the critical factor may have been his observation of his father, the wine merchant. Several of the authors I discuss either were the sons of doctors or practised anatomy. Several seem to owe their original ideas to their travels. In each case, thinking of the brain as a physical organ helps us to realise the extent to which even the greatest of intellects were crucially affected by the circumstances of their physical lives.

Eric Fernie

Would it be fair to say that this is why the first of your neural subjects is Aristotle, rather than Plato?

John Onians

Yes, absolutely. While for Plato the mind is the divine within us, for Aristotle it is a material thing and something which we share with the rest of nature. Aristotle is unashamed of treating man as an animal, and this enables him to appreciate the role of nerves in our inner life. The Greek word for nerve, neuron, is originally the word for a sinew. Once you use the same word for a sinew and a nerve, you have the idea that the nerve is actually pulling, compelling the body to make its movements. And if you think of the body in this mechanical way, it becomes easier to understand how the mind and the body are linked. For instance, it allowed Aristotle to understand something of the working of ‘mirror neurons’, that is the neurons that help us to understand and imitate the movements of those we observe. He rightly noted how if we feel or express an emotion, we can communicate it much more effectively. He understood the power of the smile that appears during his life in works such as Hermes bearing the infant Dionysus by the fourth-century Greek artist Praxiteles.

Eric Fernie

In a later chapter you call Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) the first real neuroarthistorian. Why is that?

John Onians

I think that what made Alberti special was that he was not only highly educated in subjects such as literature, mathematics and philosophy, but was also a practising artist. He made paintings and sculptures and designed buildings. This mixture of experience allowed him to write in a new self-conscious way. As he wrote books about each of the three activities, he found himself describing what went on in his mind while he was doing them, and this self-reflection allowed him to come up with perceptions that were extraordinarily acute. When he wrote about how our eye is always taken by a portrait of a familiar face in a painting, or about how we like buildings that share the symmetry of the human body, he was recognising phenomena which we know are neurologically based. Like many of the other figures that I discuss, he shows that you don’t need to know anything about the brain to come up with conclusions that match the findings of neuroscience.

Eric Fernie

Alberti writes about the classical tradition, but Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) three centuries later writes specifically about Greek art. What allows him to do that?

John Onians

The main new feature of his experience was that as a curator of Cardinal Albani’s collection he had examined more works of art more closely than anyone earlier. He felt that what he said was the direct product of his observations. He certainly writes more subtly than anyone earlier of the surface anatomy of the statues he describes. Astonishingly, he also felt that he was recovering the experience of the Greek artists who 2,000 years earlier had first gazed with intensity on the naked bodies of male athletes. Inspired by the winegrower Montesquieu’s idea that the differences between cultures stem from differences in the natural environment, he related the new qualities of Greek art to the warmth and brightness of the Greek climate.

Eric Fernie

Going forward in time, Karl Marx’s (1818–1883) chief contribution to the debate is to stress the fact that humanity is a part of nature. Again, this goes back to Aristotle. What is it about Marx that makes it important for you to draw out his adherence to this view?

John Onians

Marx is one of those people who laid down the basis for a critique of arguments on the basis of nature. For him, nothing is ‘culturally natural’. There is nature which provides a system of constraints and resources that human beings can exploit in all sorts of ways. One should always be aware of the tensions between the natural and the cultural. As he said, the Germans think that the cherry tree is naturally theirs, but in fact it was introduced as part of culture from Asia.

Eric Fernie

You present both Ruskin (1819–1900) and Walter Pater (1839 –1894). I see them as a kind of pair, but with Ruskin having a much more important and wide-ranging relevance to the issues you are talking about.

John Onians

Yes. Ruskin is the first person whose procedures resemble those of a contemporary art historian, who might ask why a particular painter paints in a particular way at a particular place and time. His favourite example is Turner. He was bought up with the art of Turner, and his sensibility to the artist is extraordinary. Ruskin writes about how people should be striving after truth. And yet he notes that when Turner is painting the landscape in Italy, he cannot get it right. The reason he gives is that he had looked with great intensity at the landscape in Yorkshire on his first big drawing expedition. Such looking, he argues, permanently affected his visual apparatus or, as we would say, his neural apparatus. So every view that he painted afterwards took on some of the qualities of a Yorkshire landscape. You might think that this makes him a bad artist, but actually, as he tells us, it makes him a great artist, since it was the intensity of his looking at Yorkshire that caused this effect. A lesser artist would have responded to Yorkshire less strongly. His or her neural networks would have not been reconfigured, and he or she would have gone on to paint Italy more accurately.

Eric Fernie

What about Pater?

John Onians

Pater is interesting because, perhaps under the influence of Ruskin, he became conscious of his own life-changing visual responses, noting how particular experiences had affected him in a very powerful way. As a result he came up with the concept of brain building. He was the son of a doctor and was brought up in a world where neuroscience was advancing and revealing the refinement of the nervous system, so he could think of the brain neurally, in a way that Ruskin, who was a generation older, simply couldn’t. So, having this image of the very fine nerves that were in the brain, he could explain how a single very intense experience of looking at crimson flowers when he was a young man could cause him to have intense relationships with almost any crimson coloured object, perhaps a textile or a painting later in his life.

Eric Fernie

In the book you say that the same discovery about the refinement of our neuro-network inspired Hippolyte Taine’s perceptive views on our susceptibility to purely passive exposure to the environment. This was also an element in the recognition in the 1870s of the movement of Impressionism. Would you like to expand on that?

John Onians

Taine (1828–1893) talks with considerable knowledge about the delicacy of our neural apparatus, and describes it in unprecedented detail. He was teaching at the École des Beaux Arts at the time and was talking to artists. He draws neuroscience into the context of artistic activity, and this made me aware that a painter living in Paris in the 1860s or 1870s could have had a new perception of vision. Their notion of what went on behind the eye might have a new subtlety, so that they could think of vision as being based on light impressions. So when Monet called a painting Impression: Sunrise 1873, and at the same time introduced a term that was to be applied to a whole group of artists, we are finding evidence for an unconscious recognition that the artist’s experience was more fleeting and allusive than could have been imagined earlier.

Eric Fernie

When I was reading the chapter on Adolf Göller (1846–1902), I was very pleased to come across his argument that the eye or the mind becomes jaded over time and this becomes one of the engines of stylistic change, promoting an increase in complexity within a tradition. That makes a lot of sense to me – boredom becoming the driver, as it were. However, he also describes traditions as flowering and decaying, which seems to me to clash with this scheme. The mind becoming jaded is a neuroscientific concept, whereas flowering and decay is simply the misplaced application of biological terminology to a historical process. This illustrates one of the benefits of neuroarthistory.

John Onians

I think that is certainly fair. Jading is, in one sense, a real attribute of our neural apparatus. Nerve cells, such as the cones in our retina, are liable to fire vigorously when first exposed to the colour to which they are sensitive, but then cease to react. Göller, though, is using ‘jading’ more loosely to draw attention to the way forms lose their appeal. And I agree that to use the metaphor of flowering and decay does make the process seem more biological than it is.

Eric Fernie

You have a run of three chapters on Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) and psychoanalysis, John Dewey (1859–1952) and philosophy, and Melville J. Herskovits (1895–1963) and anthropology, and I wondered what benefits there were in treating them as a sequence. You relate all the texts you deal with to the topic of neuroarthistory; but are any of these fields related more easily to neuroscience than the others?

John Onians

I don’t think so. What I realised as I studied these three individuals was the way each offered a different set of acute observations and dealt with a different set of phenomena. Freud is concerned with dreams and reminds us that when we imagine one thing, we may in fact be thinking of another with which it shares some property. He argues this narrowly in relation to concealed sexual imagery in dreams; today we can see that the argument has a much wider validity, as can be seen in advertising. Dewey is concerned with the way daily exposure to an artefact type affects visual preferences and so artistic style. He illustrates this by the way frequent exposure to ‘the shapes typical of industrial products’, such as cars and New York skyscrapers, contributes to the emergence of ‘Modernist’ figures. Herskovits is keen to establish that visual perception is not universal but relative. He demonstrates this by the way people brought up in different environments have different responses to optical illusions. For example, those living in a Western environment, that is one filled with ‘carpentered’ cuboid shapes, will always see the identical lines in the famous Müller-Lyer illusion as being of different lengths because of the acute and obtuse angle at their ends, while a member of the San community living in the South African desert, where there are no cuboid shapes, will have no difficulty in seeing them as having the same length. So each shows how different fields shed light on different aspects of visual art. This means that art historians who are unaware of the questions which are being asked by clinical psychologists, philosophers, or anthropologists are likely to be missing out on important ideas. And since in the above examples all the ideas have a neural basis, it is encouragement for art historians to pay particular attention to neuroscience.

Eric Fernie

How do you see Ernst Gombrich (1909–2001) in relation to neuroarthistory?

John Onians

One has to be aware that at the beginning of his period in England, in the late 1940s and the 1950s, when Gombrich was writing The Story of Art (1950), and even when he is writing Art & Illusion (1960), he is profoundly suspicious of a biological approach to anything. Living in the post-war period, and coming from a Jewish background, he is especially conscious of the dangers associated with it. But it is clear, as we move into the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, that he became more and more aware that he had been suppressing cues in his mechanism which had been alerting him to fundamentally important phenomena. And so he was very glad to start referring to biology…

Eric Fernie

How wide, then, were his biological interests?

John Onians

As I was reading Gombrich, I was at first disturbed by the way he was changing his mind, shifting his ground. But I then found myself changing my own mind. As I realised that this was what set him apart from everyone else in this book, I became conscious that what caused him to shift was the fact that he went through more environmental-cultural settings than any of the other authors in the book. During this process he himself became aware of how his mental inclinations were adapting to these changes. This self-consciousness is beautifully expressed in his observation that ‘when I visit a zoo my muscular response changes as I move from the hippopotamus house to the cage of the weasels’. I think it shows incredible courage for someone who obviously wants to present themselves as an Olympian intellectual to end up treating themselves as an animal, and it certainly shows how instinctively he adapted to changes in his environment.

Eric Fernie

You make Gombrich’s approach sound very physical, whereas with Michael Baxandall (born 1933), a pupil of Gombrich like yourself, you stress the cognitive. Could you comment on this, especially concerning his concept of the ‘period eye’?

John Onians

Baxandall’s idea of the ‘period eye’, the notion that people operating in different social frameworks have different visual preferences, and that these radically affect artistic style, is perhaps the most important idea to emerge in art history in the past 50 years. By systematically relating familiar differences in the styles of the great Renaissance masters to differences in the education and cultural values of their patrons, it provided a model that could be more widely applied to different societies. But I think that today we can recognise the limitations associated with his very useful analytical term ‘cognitive style’. The term cognitive can be used in many different ways, but the core reference of cognition is to the problem of how we know the world: cognition thus concerned Plato and has concerned philosophers ever since. And because Plato obviously wanted to minimise the role of the emotions, moods and visceral needs, the study of cognition is, to this day, often carried on as if we don’t need to consider emotions and moods and visceral needs. Cognition is some sort of higher faculty that is typical of humans, and so one which we should want to understand if we want to understand humanity. This is why thinking in terms of the cognitive is potentially limiting.

Eric Fernie

Is there a parallel here with the mind/brain distinction that we were talking about earlier?

John Onians

It’s certainly very clear that if you’re talking about the mind, you’re talking about cognition. If you’re talking about the brain, it becomes much more difficult to restrict the reference of cognition in this way. So that nowadays there are people in cognitive neuroscience who avoid talking about emotion. Indeed, it is still possible to buy a book about cognitive neuroscience in which the word emotion doesn’t appear in the index.

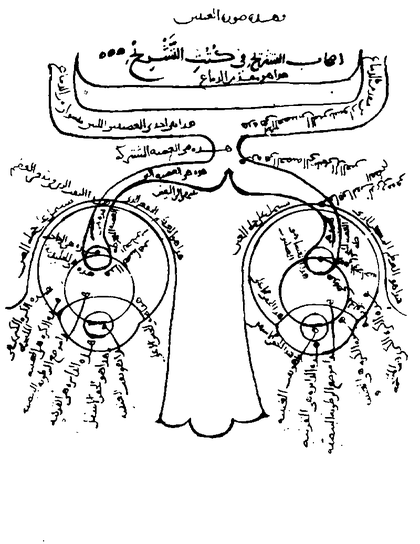

al-Haytham, drawing of eyes, brain and connecting nerves, from Neuroarthistory: From Aristotle and Pliny to Baxandall and Zeki

Published by Yale University Press

Courtesy Yale University Press© Istanbul MS Fatih 3212

Eric Fernie

The last of the texts in your book is about Semir Zeki (born 1940). One of the things he does is to analyse paintings by artists such as Mondrian, asking, for example, how the rectangles relate to one another, how they affect the viewer. Has he conducted what you might call control experiments with non-art objects such as floor patterns, and compared the results with those produced by ‘high’ art?

John Onians

Zeki is extremely unusual as a neuroscientist. Almost all research into the brain relates to the needs of medical science, which is why it is often only incidentally of value to the art historian. Zeki is asking questions that reflect his strong personal interest in the visual arts. Although he has certainly studied the neural response to plain shapes, I doubt whether he has studied responses to paving slabs. I personally have no problem seeing what the brain is doing as being similar – whether it is reacting to paving stones or Mondrian. A lot of people find that a distressing idea, because what makes them feel good about the Mondrian is precisely that they’re not paving stones. They may be rectangular, but they’re not paving stones, and you feel they belong to this higher category. In my view, it is quite clear that there is a greater interest in the Mondrian than there is in the paving stones, because when Mondrian was making a painting, he was looking with extraordinary intensity and moving his brush with great subtlety and alertness to create effects which were extremely dynamic or pleasing, emotionally gripping to his brain, whereas the person laying the paving stones is not doing that. If a lot of neural activity has gone into making something, it is likely that viewing it will elicit comparable activity. Some people may think that studying the responses to paving stones may be degrading ourselves, but it emphasises the significance of the Mondrian.

Eric Fernie

I am not worried about us degrading ourselves. What I want to see is the different results from approaching the paving stones and the Mondrian in the same neuroscientific way, if there is a difference.

John Onians

I suspect that those results would interest Zeki too. He has already explored what makes the difference between an average work of art and a masterpiece. He writes very movingly, for instance, of the way we respond to Michelangelo’s unfinished sculptures, because the brain needs to deal with and resolve the indeterminate. He sees that as being of fundamental importance. If you follow his argument, if Michelangelo had finished those sculptures, their power as masterpieces would have been diminished. That’s a very clear hypothesis.

Eric Fernie

But is it a neurological hypothesis?

John Onians

Yes, in the sense that it can be tested by neuroscientific experiments, comparable with those Zeki has run on the response to Fauvist imagery. If I remember rightly, in a very compelling experiment he shows that if you scan the brain of someone looking at a strawberry that is naturally red or a strawberry painted red, you see neural activity being concentrated in the temporal lobes, the area where strawberries are identified and categorised. If you have a painting of blue strawberries, on the other hand, the brain becomes extremely active looking for a place to categorise them, and also trying to relate it to all sorts of things. A Fauvist painting of a strawberry is much more intellectually engaging than a red strawberry.

Eric Fernie

How does that relate to the unfinished work?

John Onians

In an unfinished Michelangelo we see both anatomical details, such as a beautifully carved elbow, and raw stone, and this presents the brain with a problem, as they are dealt with in different areas of the temporal lobes. Not only are the two categories incompatible, but the areas that deal with them are also associated with connections to other unrelated areas of the brain. This means that the brain is liable to become more active than usual.

Eric Fernie

I can see that, but there is still a great difference between a strawberry painted blue and a work that is conceived to be unfinished. The status of these two things is very different.

John Onians

What they have in common is that the brain has great difficulty resolving their identities.

Eric Fernie

Turning from the authors to general considerations, I know that you have encountered resistance to this project. One of the reasons for this appears to be that critics object that neuroscience introduces determinism into the study of the visual arts. Would you like to comment on that?

John Onians

When people use the word determinism in this context, they are drawing attention to the extent that treating humans as biological organisms necessarily reduces the freedom we credit them with. They don’t like this, because it makes them less godlike, but I am afraid that we have to accept that we are not godlike in our freedom. I happen to be colour blind and that fact has a determining effect on some of my reactions to visual stimuli. We simply have to learn to be intelligent in our determinisms. A neuropharmacologist has to be subtle in assessing the extent to which a drug may have determining effects on a patient’s behaviour, while a neuroarthistorian has to be subtle in assessing the way particular inborn predispositions or later experiences may affect an artist’s production. It’s clear that if you’re brought up surrounded by snow, just as you can’t plant corn and expect it to grow, so you’re not going to have anything like the same response to colour that you would have if you’re brought up in the tropics. You would probably not expect to find a lot of exploitation of colour in the art of the Eskimo or the Inuit.

Eric Fernie

Can you point to specific examples of resistance?

John Onians

Ten years ago I was asked by the guest editor of a journal published in France to contribute an article on the biological origins of art, only to have it turned down by the management. And around the same time two friends at major American universities said ‘we’d love you to give a talk, but you can’t talk about that stuff’. It was only when I made a connection between these reactions that I realised that the French and the Americans both have in common an almost religious belief in the importance of freedom. This means that they have some problem with the idea that we are constrained by our genetic make-up, and that being exposed to different environments unconsciously affects our behaviour. To invoke biology in this way may even seem problematic in terms of these countries’ constitutions. The other point, which people might make in England, is that the biological explanation of culture brings to mind the arguments of the Nazis and those in favour of eugenics and reminds them of all the negative consequences that followed. The situation is rather the reverse. The great thing about modern neuroscience is that it sets us free from those arguments. Whereas someone such as Adolf Hitler would say the brain of this race is absolutely different from the brain of that race, the neuroscientist says that whatever your race, the human brain is essentially the same. The reason why our brains are so different is because of the plasticity we were discussing earlier. Neuroscience brings out all those properties which we celebrate in humanity – flexibility, variability and individuality.

Eric Fernie

How do you see neuroarthistory affecting the concepts of conventional art history, with periods such as the early Renaissance, the Baroque, etc?

John Onians

Let’s imagine an example. Suppose I am living in Florence in the fifteenth century and I am building this big cathedral with pointed arches. I get pleasure out of the pointed arches because I think they are spiritual and Christian. If, however, the Duke of Milan begins an even bigger cathedral with more pointed arches as an expression of the fact that he is the representative of the German emperor and wants to take over Florence as part of a German Empire, I would suddenly realise that these arches are, in fact, emblematic of foreign domination. So the pleasure you got out of them evaporates, and instead you get pleasure out of looking at a round arch which is associated with the period when it was Italians who controlled Germans. What neuroscience says is that everybody in Florence, whether they’re a beggar on the corner of a street, or whether they’re a member of one of the wealthiest families, or whether they’re an architect or painter, is going to have less pleasure in pointed arches and more in round arches. And it seems to me that this helps to explain why, at the time of the Milanese invasion in the 1420s, there is such a rapid and complete abandonment of a Gothic vocabulary. In other words, if you are not aware of these changed neurochemical responses, it’s more difficult to explain why things move so quickly.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Arsenale, Venice, from a Canal below the Walls (1840)

Tate

Eric Fernie

I’m still not convinced. Let me see if I can put my uncertainty in terms of a parallel? Ruskin’s explanation of why Turner’s Tuscan landscapes are not in fact very naturalistic seems to me to be an aperçu from the field of neuroscience which helps to explain a characteristic in Turner’s work that you can’t explain otherwise. At least I can’t think of what you might call a cultural explanation. Whereas what you are describing in the case of the change from the pointed arch to the round arch strikes me as being something which has an historical explanation, where the neuroscientific input has much less explanatory value.

John Onians

I think you’re quite right. And what you bring out is that the use of neuroscience should not lead us to look for explanations in only one area. Any neuroscientific explanation should be fed into existing explanatory models. It may then help us to understand something about the speed, direction or completeness of stylistic change. But, having said that, it is also worth remembering that there is a neural element to lots of influences which we think of as cultural. When a northern artist reads a book about perspective, he will be influenced by it only to the extent that his neural resources are affected by it. When we read a book, we think of ourselves as merely having learned something, but the truth is that our neural networks have been reconfigured by it, just as they might be by passive exposure to the environment.

Eric Fernie

Finally, you mention the origins of art. It seems on the face of it that neuroscience should have a great deal to say about that. Do you agree?

John Onians

Absolutely. It is likely to be particularly helpful in that field because there are so few other ways of getting at what went on in people’s minds 10,000, 20,000 or 30,000 years ago. To give you an example, other available approaches have little to say on why the paintings in the Chauvet Cave in southern France, dating from before 30,000BC, are not only the earliest, but also much the most naturalistic. A knowledge of neuroscience, and especially of neural plasticity and mirror neurons, seems to me to provide answers to both those questions. This will be the topic of the first chapter of my next book, where I apply neuroarthistory to problems from the whole history of European art, right up to the art of Marcel Duchamp at the beginning of the twentieth century and of the YBAs.

Marcel Duchamp

La boite en valise 1949

Private collection © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002

Eric Fernie

What might neuroarthistory add to the discussion of Duchamp?

John Onians

This is not a definitive answer, but in relation to his readymades, it is clear that the objects he introduced – a urinal, a bicycle wheel, a bottle rack and so on – had become so familiar as valuable devices that viewers would necessarily have enjoyed seeing them. They might not have placed them in the category of art, but the response they evoked was one at the centre of artistic experience, an unconscious pleasure, a pleasure enhanced by the additional references associated with title and text and context. It was such a neurally-based response that Duchamp unconsciously exploited.