The camera has always been a socialised instrument, well equipped to describe shifting behaviour, environments and manners. Of course we rely on it to give a specifically factual account of them. Inevitably, situations change, but this testimonial function of photography remains constant. Before the advent of Photoshop, whatever the circumstance or event, be it impromptu or staged, there could be little doubt that the camera recorded it through an act of witness. Its observational power would appear to have served as a fixed, credible reference to realities that fluctuate indefinitely. Over the past few decades, however, we’ve come to understand that a scene may be filtered through photographic motives other than, or at odds with, the purpose apparently intended. The facts are delivered, but their content has to be reckoned with freshly, and on uncertain terms.

As this recognition has dawned, certain earlier guides to the interpretation of photographic images have correspondingly fallen away. Some of them had been based on hierarchical models of technological advance or formal innovation. For a long time a more horizontal scholarship traced the evolution of photography as a chronicle of its genres and modes. These pointed to the original use of an image, whether it was a passport photo, a family snapshot, a celebrity picture, or a street document. Each of them was an artefact designed to satisfy a particular, mundane need. Photographic output was, and still is, an aggregate of corporate or official interests, activist politics, artistic vision and industrial folklore. Photographs were distinguished by their appeal to readily identifiable audiences or publics, who tuned in a genre wavelength to get the designated message.

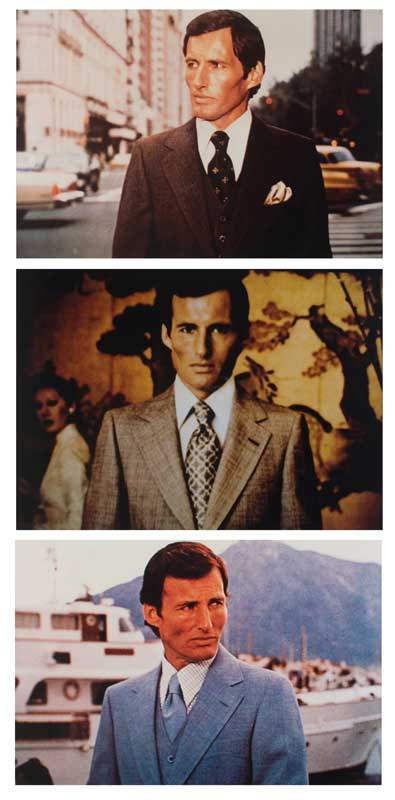

Richard Prince

The same man looking in different directions 1978

Ektacolor photograph

50.8 x 61 cm

Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York © Richard Prince

Yet, even in the nineteenth century, viewers would have been familiar with some degree of overlap among various photographic practices. In developed countries, an ethnographic representation of non-Western tribal life could have tourist overtones. Cartes-de-visite were not just calling cards, they frequently operated as early fashion plates. This doubling function has spread so far nowadays that it’s hard to speak anymore of the genre system as a set of monocultures, each with its targeted clientele. Some fashion work, such as Richard Avedon’s, was affected by sports photography. An impassive, self-conscious work of art by, say, Thomas Ruff might well be intended to mimic a mug shot. Within the miscellany of an urban scene, an individual might stand out, cast as the inexplicable centre of attention of a portrait. Without asking so much as the viewer’s leave, photographers have deprogrammed the genres and tossed media in a juggle of unexpected meanings. They remind us, if only by contrast, of how often our understanding of photographs originates on the basis of their decorum – imagery and style proper to the media occasion. But in consumer society, rules of decorum are chronically redefined or even subverted in the search for novelty. Many of the images we see around us today have no trouble communicating that impulse. Technological advances condensed or interrupted the work of photographic propriety; boredom with formulae deflected it; urgency diminished it. In fact, restless media have affected (if they haven’t exactly shaped) conduct, made it more open to psychological discovery and to epochal disturbance.

This is one story suggested overall by Street & Studio: An Urban History of Photography. As its title indicates, this huge exhibition operates as a survey of portraits tagged by their origin in the marketplace of cities. Within that zone, the show locates two evident portrait traditions – of the street, roughly speaking, and the studio. If considered side by side, they should induce what one might call a double ledger view of portrait genres, one column devoted to action and a spontaneous transparency of expression, the other absorbed by the theatrics of conscious self-proposal. On one hand, we have the rapidity of the photographer’s glimpse, in a heated, fluttering moment, on the other, the weightiness and concentration of his or her stare during a sitting. Between such familiar archetypes, there would seem to be a distinction – and there often is. One has only to consider Cartier-Bresson’s and Irving Penn’s post-war portraits to visualise the polarities at issue. But as they evolved, they also mingled. Nervous crosscurrents stirred the waters underneath, and injected them with confusing rhythms. As for the excited ambience of the city, it acts as a crucible in which the random as well as the formal characteristics of portrait genres are warmed and made volatile.

Meanwhile, a portrait photograph obviously does more than record a social context, it instigates subliminal or conspicuous interactions among those who have put it together. They were people who could not always be counted on to behave as desired, even when given orders. Aside from any utilitarian consideration, their demeanour was in itself inherently dynamic, prone to the opportune and unequal assertions of one or all of the agents involved. Impulsive street work and posed studio portraiture have distinct forms of address, but they can yield equally fugitive, enigmatic and subtle impressions, however different in scale.

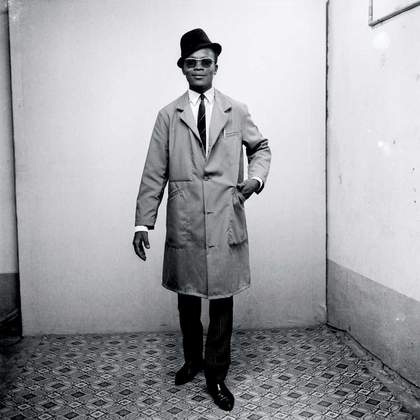

Malick Sidibé

Man in Business-dress, like a pedestrian 1964

Gelatin silver print

45 x 45 cm

Courtesy Association Gwin Zegal © Malick Sidibé

Jacob Holdt

Cross burning in Alabama 1970–5

from American Pictures, a series of 15,000 photographs taken with a pocket-size Canon Dial camera during a trip around America

Courtesy the artist © Jacob Hold

Normally, we think of the street as the locale of figures, not faces; of ‘there’, not ‘here’. Yet a closely observed physiognomy in a studio is the site of as many uncontrollable moods and variables as those available at further range on the street. Of course it matters if the framing is broad or the emphasis is restrictive. But in the end, whether faces are the subject of a consented portrait transaction or a roving, unauthorised and impulsive click, they yield a voyeuristic outcome, constructed within an imaginative space. A good example is Martin Parr’s hybrid Autoportraits, a series he began in the 1990s, using tourist portrait shops around the world. It’s organised as a project with one theme, his repeated presence amidst many variations, the disparate novelty backgrounds of the shops themselves. They have the hokey flavour of old postcards and fairgrounds, while he himself carries on with a solemnity that never gets into their spirit. Whether in Odessa, Amsterdam, or Havana, Parr presents himself as on vacation, wearing sporty clothes not indigenous to the locale. Very well. But you can come away from these pictures sensing that something is evidently – and comically – amiss about them. This reticent and oddly boyish middle-aged man is in the scene, but somehow makes sure you know that he doesn’t belong there. It’s a droll effect brought out by his conceptual humour – his appropriation of a vernacular mode, into which he willy-nilly allows himself to be taken hostage. He’s not so much a client of the photographers as a student of their genre. It holds an anthropological interest for him, even though it requires him to compromise whatever persona he puts on for the occasion. Some of these pictures are dreamy, as if Parr, an urban sophisticate, had wandered into anachronistic Salon portraiture. But it remains the real, tacky thing, still flourishing in provincial districts. In the end he can’t conceal his nostalgia for a genre that he colonises with gentleness and affection.

Out in the street itself, there can’t be a dialogue between then and now – it’s all just one moment – but the notional accents of ‘here’ and ‘there’ may well be switched. Helmar Lerski’s hyper-close examinations of faces in his 1920s studio were impossible to bring off without the prior consent of the subject. But Leon Levenstein made grabbed and surreptitious counterparts of those Lerski pictures 30 years later, among city passersby. In both cases, the face looms at uncomfortably close quarters – so near, in fact, that a viewer is prevented from imagining any social relationship with it. The personal territory of the subject had been violated, along with the decorum of portrait genres, and yet it’s difficult to call such chafing photographs anything but portraits. Even more peculiar, the defenseless subjects exert an almost sinister power over the viewer, who is unable to back off.

In the matter of brusque encounters, consider Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s Heads series (2000), where urban pedestrians have been singled out with the telephoto lens at the moment they were illumined with a hidden flash. Their ambiguous, highlighted proximity lends to these city dwellers the effect of being in a studio or movie set, and under intimate scrutiny, whereas the photographer could only have guessed at the effect, without any chance of seeing it. The Heads series comprises real street shots pretending to be studio portraits. By such means, diCorcia asserts an actually tenuous control over chaotic material, and brings to it an implausible drama.

Whatever their state of preparation, there can be no doubt that contingency also plays a role in such manoeuvres. The cross-fertilisation of genres and their modes might just as well be the result of happenstance as of artistic intent. Jacob Holdt was a penniless Danish hippie wandering in Nixon’s America, whose racism brought him to the boil. Sheltered along his travels by numerous African-Americans, this gifted picture maker took slides in the manner of the family album. Often, in fact, he regarded his fellow down-and-outs as members of his surrogate families. The results were intimate and, with their revelation of gruesome poverty, appalling in equal measure. It was rare for affectionate interludes such as those pictured by Holdt to serve as the indictment of a society. When he showed them later in illustrated lectures, they must have seemed very dissonant pictures indeed.

But contingency might just as well have its way in a straightforward genre where the mood was unquestionably affirmative. Malick Sidibé operated as a commercial studio portrait photographer in Bamako, the capital of Mali, during the 1960s. The young mods he photographed in their dance clubs look like they’re in the throes of jiving, but Sidibé could realise that effect only through the most acute, finical composition. Even though – or maybe because – it had to be a charade, the spontaneity of his subjects is amazing, and wonderfully charming. Holdt was a didactic amateur and Sidibé a scrupulous professional who needed to conceal his craft in order to appear loose. Here were two transgressors of photographic protocols by virtue of their conflicting drives, not by artistic design.

Rineke Dijkstra

The Buzz Club, Liverpool, England, March 11, 1995 1995

C-type print

48 x 35 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery © Rineke Dijkstra

Rineke Dijkstra

The Buzz Club, Liverpool, England, March 11, 1995 1995

C-type print

48 x 35 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery © Rineke Dijkstra

Yet when artistic consciousness does inform genre slippage, the result is often compelling. Levenstein and Lerski were clearly Modernists, while Parr and diCorcia are Postmodernists. From the abstract, graphic energy of the first pair, one moves to the suave, yet perverse displacements of the second. The transition is interesting because it betokens the entrance of a new problem in the history of photography. For some time, we’ve been breathing an atmosphere where photographic media reflect upon themselves, even as some imagists within them claim an artistic vantage outside the media. Modern art is notable for ingesting popular media, either for ironic or topical comment. As media contrive nothing less than our image environment, and therefore convey vital subject matter, they could hardly be overlooked. But they were – and are – appropriated by artists on a “higher” conceptual plane, legislated as long ago as Cubist collage. A kind of internal collage has infiltrated the publicity functions and the industrial folklore of photography. Where portraits are concerned, this process has reflected a humanity at some variance from the way people appear in known genres. Historians like to structure modern art according to its presumed order of movements and phases. That structure is now eroded within the myriad compartments of photographic culture, whose workers are apt to put on more or less convincing airs of artistic consciousness. Undeclared motives now mingle in a traffic of untoward expressions. Innovational modern art never had a strict genre structure to break down and depart from. For want of a new territory to conquer, the fictional energies of art have penetrated into the factual and material basis of photography. Presently, we see that a picture land has appeared, expansive yet uncharted in its shape. We behold acts of witness that are frequently muffled and media messages that are increasingly scrambled. ‘High’ and ‘low’ do nowadays get on with each other, sometimes easily, yet sometimes not. What remains clear is photography’s dependence upon the indispensable constraints that it is leaving behind. Without them, we would be hard put to notice the difference between how things look and the way they are made to look. The generic is too useful to have seen its time, but meanwhile, let us be grateful for the genres.