Better known as the author of The Dong with a Luminous Nose and other classics of nonsense verse, Edward Lear was also an intrepid traveller and accomplished draughtsman.Ill health and a depressive nature forced him to seek the warmer climate of southern Europe, but it was his constant search for new subjects as a “painter of poetical topography” that inspired his journeyings further afield to Egypt, the Near East and even India. While travelling, he kept journals – some of which were published along with his drawings – and wrote extensive and eccentric letters to his friends. Reflecting both his insecurities and his irrepressible humour, these texts add a remarkable – and delightful – extra dimension to the numerous images that he drew and painted. His recognition of this is perhaps suggested in one of the quirkiest of his self-descriptive aphorisms, when he wrote to his close friend Chichester Fortescue that he considered himself the ‘Greek Topographical Painter par excellence’ and aspired to the title of ‘Painter-Laureate and Grand Peripatetic Ass and Boshproducing-Luminary-forthwith’.

For many of the artists during the mid nineteenth century who also ventured east, writing was almost as important as sketching. Some, such as Lear, William Holman Hunt and David Roberts, kept daily journals and wrote letters to friends and patrons at home. Richard Dadd wrote few but poignant letters to fellow artists. Others, such as John Frederick Lewis, are notable for their silence. When their correspondence has survived it affords insights into the artists’ aspirations as well as their diverse motives for travelling east. Most tangible of all, we can gain a sense of what it was like physically to travel in these countries – Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and what are now Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian Territories. Then, as now, the political and religious stability of these places was never certain. Egypt, under the tough control of the Ottoman sultan’s semi-autonomous pasha, Muhammad Ali, was relatively safe, but ‘Greater Syria’, especially the area then known as the Holy Land, was in a state of spasmodic political turmoil, with rivalries between Arab tribes, as well as between Muslim, Christian and Jew.

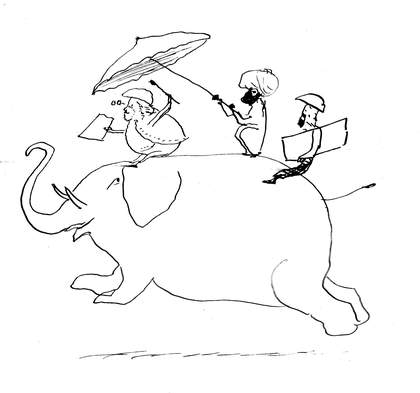

Edward Lear

Drawing of the artist and Giorgio on an elephant, from a letter to Lady Waldegrave, dated 25 October 1873

Sepia ink on paper

21.6 x 29.2 cm

Courtesy Somerset Record Office, Taunton

For all the artists, modes of transport were basic. Travel along the Nile was by slow but leisurely boat, while trips across the desert and in the mountains were either on horseback, or, most uncomfortably, by camels. Accommodation too was unpredictable: for Dadd it was “a ruined house which could scarcely hold its ricketty sides together, a mud hut, or greasy Greek house… and we often were and are the victims of the hungriest fleas that can exist”. Roberts sometimes enjoyed the hospitality of monks in a monastery, but preferred the independence of life under canvas, even though occasionally he was at the mercy of fierce desert storms: “To creep under the belly of a Camel would have been a luxury had I not had to hold on by the polls of the tent, portmantu beds clothing eatables were all deluged.” And sketching their subjects was no easy task either – the excessive heat, dust and flies were bad enough, but sometimes they were pelted with missiles, threatened and robbed. At Petra, Lear’s pockets were emptied of everything “from dollars and penknives to handkerchiefs and hard-boiled eggs, excepting only my pistols and watch.”

Why did these artists go there? David Roberts, among the earliest of British artist travellers, professed himself to be fulfilling an ambition “from earliest boyhood, to visit the remote East”. But he was well aware of the commercial and social rewards that scenes of ancient Egypt and the Holy Land would bring him from a public hungry both for novelty and for apparently true records of biblical places, and he knew that he was bringing back “one of the richest folios that ever left the East”. Occasionally, he encountered difficulties in transferring to paper the size and magnificence of tombs and temples: at Karnak he was “overwhelmed… with astonishment” and was “fearful painting will scarcely convey any notion of what I mean”, but his training as a stage-scene painter had equipped him well for such large-scale challenges. He returned with 272 coloured drawings and three full sketchbooks. By contrast, a few years later Richard Dadd, travelling with his patron Sir Thomas Phillips and covering a greater distance more quickly, was much less prolific, and the 191 closely-drawn sheets from his sketchbook and a handful of coloured sketches probably represent the bulk of his output. He found the unfamiliar sights inhibiting, confessing in a letter to Roberts: “As you promised me before starting the interest of these places is intense and when one enters their streets the quantity of character is distracting, so much so as to hinder me from sketching for I could not make up my mind what to do amidst so much to be done.” There were “a thousand things to arrest the attention”, but “all seemed to slip away from me as if unreal as if they were the pageants of a dream rather than a substantial reality”. His excuse was the speed at which they travelled, “for a body cant very well sketch riding on horseback”, but his confusion may have been an early symptom of the terrifying delusions and insanity from which he subsequently suffered.

Richard Dadd

The Flight out of Egypt (1849–50)

Tate

In comparison, John Frederick Lewis’s experience of the East was almost sedentary. He spent nearly ten years living in a Mamluk-style house in Cairo, with an occasional trip to the Sinai desert and only one known voyage on the Nile. If he wrote a journal or extensive letters home, they have not survived, and we have to rely on the comments of the few English visitors who met him for glimpses of his apparently cross-cultural existence. Dadd reported to Roberts that Phillips had seen his sketches, and that Lewis was intending to return soon and “reap the harvest of his labours”. In fact, he remained another eight years, becoming an elusive and enigmatic figure, whose supposed lifestyle as a pipe-smoking “languid Lotus-eater”, wearing an “embroidered jacket and gaiters, and a pair of trousers which would make a set of dresses for an English family” and as the overlord of a “long, queer, many-windowed, many-galleried house”, was given almost legendary status by his friend William Makepeace Thackeray, who wrote about his visit to Lewis in his Notes of a Journey from Cornhill to Grand Cairo (1846).

William Holman Hunt’s approach was very different. He believed it his Christian duty to paint religious subjects in biblical locations. Both The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple 1854–60 and The Scapegoat 1854–5 were painted from life, the latter at Usdum (Kharbet-Esdoum), the desolate, southern end of the Dead Sea, of which he wrote in his journal, “never was so extraordinary a scene of beautifully arranged horrible wilderness”. Later in Jerusalem he expounded his ideology in a letter to the writer William Michael Rossetti: “I have a notion that painters should go out, two by two, like merchants of nature, and bring home precious merchandise in faithful pictures of scenes interesting from historical consideration, or from the strangeness of the subject itself… It must be done by every painter and this most religiously, in fact with something like the spirit of the Apostles, fearing nothing, going amongst robbers and in deserts with impunity as men without anything to lose, and every thing must be painted even the pebbles of the foreground from the place itself, unless on trial this prove impossible… I think this must be the next stage of the PRB [Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood] indoctrination and it has been this conviction which brought me out here, and which keeps me away in patience until the experiment has been fairly tried.”

William Holman Hunt

The Scapegoat 1854–5

Oil on canvas

33.7 x 45.9 cm

Courtesy Manchester Art Gallery

For the topographical painters, Jerusalem presented problems. A decade and a half earlier Roberts declared that he “never had more uphill work than in sketching the various objects of interest about Jerusalem. The city within the walls may be called a desert, two thirds of it being a mass of ruins and corn fields; the remaining third with its Bazaars and ruined mosques being of such a paltry and contemptible character that no artist could render them interesting”. His Jerusalem subjects, though numerous, are mostly from outside the walls, as were Lear’s, nearly twenty years later. Like many western visitors, Lear was appalled not only by the decay into which the sacred city had been allowed to fall, but also by the internecine strife between the representatives of the various Christian sects supposed to be guardians of the Holy places. “O my nose! o my eyes! O my feet!” he wrote, “how you all suffered in that vile place! – For let me tell you, physically Jerusalem is the foulest and odiousest place on earth. A bitter doleful soul=ague comes over you in its streets – & your memories of its interior are but horrid dreams of squalor & filth – clamour & uneasiness, – hatred & malice & all uncharitableness. – But the outside is full of melancholy glory –: exquisite beauty & a world of past history of all ages: – every point forcing you to think on a vastly dim receding past – or a time of Roman War & splendour… or a smash of Moslem & Crusader years…”

The tendency to historicise both landscape and population of the Near East was commonplace among western travellers throughout the nineteenth century. On a later visit to the Holy Land, Hunt wrote: “I feel as I go about the country, that I pass not merely from a village to a town, and from a town to the desert and an Arab encampment, or to a night’s rest under the unscreened stars, but from one century to another, from the days of Abraham to those of Cambyses, Herodotus, Alexander, Jesus Christ, Mohammed, the Crusaders, and on to and back again from our own day.” And this was reflected in his choice of subjects: he had entitled his painting of a Nile peasant woman The Afterglow in Egypt 1854–63 to indicate “that the light is not that of the sun, and although the meridian glory of Egypt has passed away, there is still a poetic reflection of this in the aspect of life there… the strong second glow which comes in the East when the sun has sunk a few minutes”.

This strong sense of the past informs many of these artists’ portrayals of the Near East and was, in their eyes, a sad contrast to the state of degeneracy that they believed existed in parts of the countries through which they travelled. (For Roberts, Philoe [Philae] was “a paradise in the midst of desolation”.) But while the poverty and misery that they abhorred are vividly described in their journals and correspondence, these harsh facts seldom intrude into their visual records – such realism would be too unpalatable for the audience at home. At Edfou [Edfu], where the temple was all but buried under houses and mounds of rubbish, “the inhabitants appear most wretched in condition”, observed Roberts. And of the people tending the fields near the river, he wrote: “The rags and filth in which they are enveloped absolutely infect the air, true, their hair is not smeared with Oil as is that of the Nubian women but then their skin is beastly, to use too good a word.” At the same time he admired as glorious “the effect of the setting sun upon the distant hills and the banks of the stream”. Lear was equally appreciative of the Nile scenery: “So far it is a magnificent river, with endless villages – hundreds & hundreds on its banks, all fringed with palms, & reflected in the water: – the usual accompaniments of buffaloes, camels, etc. abound, but the multitude of birds it is utterly impossible to describe… The most beautiful feature is the number of boats, which look like giant moths.”

Robert Scott Lauder

David Roberts, 1796–1864. Artist (In Arab dress) 1840

Oil on canvas

133 x 101.3 cm

Courtesy National Gallery of Scotland

While observing the scenery and its inhabitants, several artists were aware that they cut an odd figure in such surroundings, realising, with wry humour, that they too were the subjects of scrutiny. Roberts describes wearing “a straw hat, cocked… a little to one side… a cigar stuck in my mouth, a French blouse and the usual narrow coverings of the lower extremities which after a Turk’s yard wide ones must appear scanty enough”. Hunt uncompromisingly wore western dress at first, ridiculing his friend Thomas Seddon’s attempts at adopting local costume, yet subsequently both Hunt and Roberts found it convenient to don some form of Oriental attire. Many years later Hunt posed for a photograph in which he re-enacted his experience of painting The Scapegoat, with a keffiyeh on his head and his qumbaz suspended from his easel. On their return, both artists, acutely aware of their public image, sat for portraits wearing Oriental costume, keen to stress their roles as artist-travellers in the East. Roberts in his portrait by fellow Scottish artist Robert Scott Lauder is presented in fancy dress turban and robes in a romantic memorial of his epic voyage; Hunt in his Self-portrait 1867–75 wears an authentic qumbaz and, grasping his palette, projects an image of a serious artist with a self-imposed mission.