24 February 1970

Nigel Greenwood Inc. Ltd. opens in London

Barry Le Va installing Extended Vertex Meetings: Blocked: Blown Outward, Nigel Greenwood Gallery, London, 1970

Courtesy Nigel Greenwood Gallery Archive

Tate Archive TGA 20148

Nigel Greenwood, a former student of the Courtauld Institute of Art and employee of the Axiom Gallery, ran his own gallery from 1970 to 1979 in west London, first at 60 Glebe Place and then at 41 Sloane Gardens. Nigel Greenwood Inc. Ltd. was the first gallery in Britain to give one-man shows to Ed Ruscha, Dan Flavin, Bruce Nauman, Keith Sonnier, Barry Le Va and Richard Tuttle.

Greenwood’s activities were not limited to the gallery. The critic Richard Cork recalled that ‘as early as 1971, Greenwood managed, in collaboration with Anthony de Kerdrel, to invade the West End and enable Barry Le Va to make a spectacular floor-piece with blown white flour, transforming a monumental space in Old Burlington Street’.1

5–31 May 1970

Installation view of the exhibition Larry Bell / Robert Irwin / Doug Wheeler, Tate Gallery, London, 1970

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Larry Bell/Robert Irwin/Doug Wheeler 1970

Installation view of the exhibition Larry Bell / Robert Irwin / Doug Wheeler, Tate Gallery, London, 1970

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Larry Bell/Robert Irwin/Doug Wheeler 1970

In his foreword Sir Norman Reid, the Tate Gallery’s director from 1964 to 1979, described the exhibition in his foreword to the catalogue as ‘in several ways an unprecedented one in the history of the Tate’.2 Rather than present individual works, the three artists created ‘complete environments’ in the Sculpture Halls (now the Duveen Galleries). Reid also claimed that the exhibition was ‘the first large scale demonstration in London of art from Los Angeles’, and that it was unusual for the gallery to give such prominence to artists ‘relatively unknown in this country’.3

Critics remarked on the exhibition’s disorientating effects. Marina Vaizey claimed that ‘many visitors were uneasy to the point of asking where the exhibition was when they were in it’.4 Robert Melville in the New Statesman described Larry Bell’s installation as ‘the blackest darkness I have ever seen’.5 Guy Brett, by contrast, saw the exhibition’s distinctive aesthetic as indicative of broader differences between Britain and America: ‘the cool precision of these rooms, the easy way electricity is handled, is very seductive and exciting, especially in Europe where it sometimes feels as though we are still sweating in the age of steam’.6

24 June – 16 August 1970

Claes Oldenburg

Tate Gallery

Claes Oldenburg

Soft Drainpipe – Blue (Cool) Version 1967

Tate T01257

© Claes Oldenburg

Oldenburg’s work had been shown previously at the Robert Fraser Gallery in London in 1966 and in group shows such as Pop Art at the Hayward Gallery, London. As with many other American artists, however, it was with a touring exhibition organised by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, that Oldenburg had his first solo show at a prominent UK institution.

Marina Vaizey, a critic writing in the Financial Times, was impressed: ‘Oldenburg is not only an artist, but the artist that at the moment our society deserves most’.7 His Soft Drainpipe-Blue (Cool) Version 1967, shown in the exhibition, was bought by the Tate later that year.

25 July – 31 August 1970

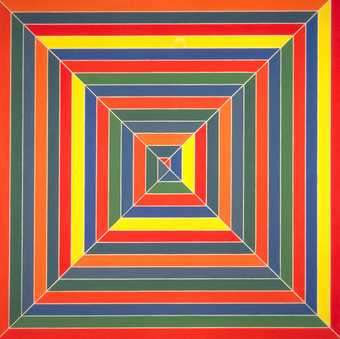

Frank Stella: A Retrospective Exhibition

Hayward Gallery, London

Frank Stella

Hyena Stomp 1962

Tate T00730

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017

Stella’s work had previously been shown in London by John Kasmin and in the Tate Gallery exhibition Art of the Real. This exhibition, organised by the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, signalled institutional recognition, but his art was not universally admired in Britain.

The critic Marina Vaizey, writing in the Financial Times, considered Stella to be ‘on the side of the decorators’ and lacking the gravity of Mark Rothko, whose recent gift to the Tate Gallery of a suite of paintings had been installed in a dedicated room. She concluded: ‘at the Hayward at the moment there is a collection of paintings which aspire to grandeur and fall memorably short, and a playfulness that is masquerading with the aid of the critics as real art’.8 In the Times Guy acknowledged the enduring power of the artist’s early work but felt that his recent work was ‘bombastic’ and showed him to be ‘cultivating a field of stylish taste’.9

Named after a fast-paced jazz composition by Jelly Roll Morton, Stella’s Hyena Stomp 1962 was purchased by the Tate Gallery in 1965.

14 January 1971

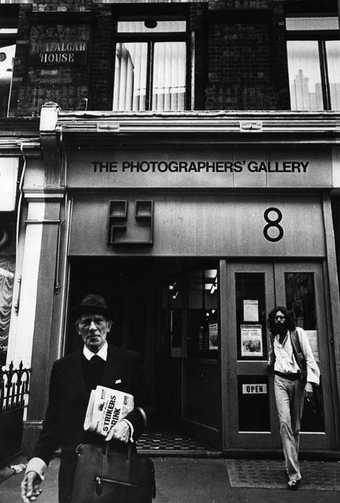

Opening of The Concerned Photographer, the inaugural exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery, London

Dorothy Bohm

The facade of The Photographers’ Gallery, London 1971

© Dorothy Bohm

The Photographers’ Gallery, established in 1971 in a converted Lyons Tea Shop in Covent Garden, London, was the first gallery in the world to be devoted solely to photography. Beginning with The Concerned Photographer, curated by the photojournalist Cornell Capa and previously shown in New York, the gallery exhibited the work of numerous American photographers. During the gallery’s first decade these included: New Photography USA (30 March – 30 April 1972) which featured Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand; Young Americans: Frederick Cantor, Paul Diamond, Robert d’Alessandro (25 April – 25 May 1972); Nina Howell Starr: Pictures of American Folk Art (14 September 1972 – 30 September 1972); Ten American Photographers (6 February-3 March 1973); The f/64 Group (28 May 1975 – 28 June 1975); an Irving Penn retrospective (1–31 October 1975); a Lee Friedlander exhibition (11 February – 6 March 1976); William Klein: Photographs 1954–1964 (15 January – 18 February 1978); Ken Josephson and Joel Meyerowitz (7 June – 7 July 1979); and Weegee the Famous (9 April – 4 May 1980). In 1980 the gallery was able to expand after purchasing a second site on the same street; it relocated to Ramillies Street, off Oxford Street, in 2012.

17 February – 28 March 1971

Andy Warhol

Tate Gallery

Andy Warhol

Marilyn Diptych 1962

Tate T03093

© 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ Artists Right Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

Like the Roy Lichtenstein exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1968, this exhibition was originally selected and organised by John Coplans for the Pasadena Art Museum. It was also shown in Chicago, Eindhoven, Paris and New York. Tate director Norman Reid described the show as ‘a survey of Warhol’s work (as painter and sculptor) as a whole’, but at the artist’s request the show omitted all of his work prior to 1962 and limited his compendious output to five themes (soup cans, Brillo boxes, portraits, disasters and flowers).10 ‘This produces the desired cumulative impact’, wrote the critic John Russell, ‘but its final effect is unduly monolithic’.11

For this reason, it was useful that other Warhol exhibitions could be seen at the same time: early drawings at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Polaroid photographs at the Photographers’ Gallery and a variety of graphic works from 1961 onwards at the Mayfair Gallery, priced from £85 to £13,000. Critics were puzzled that none of these galleries had organised screenings of Warhol’s films.

For Guy Brett, Warhol’s detachment and ‘remarkably melancholy paintings’ reflected a ‘collective American feeling’.12 Marina Vaizey asked, ‘who can forget or dismiss Warhol’s electric chair, mushroom cloud, Jackie, Liz, Marilyn, Elvis, or deny that these terrifyingly beautiful icons are integral to our transatlantic life and times?’.13 Warhol also gave his own opinion of the exhibition: ‘It’s good.’14

Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych 1962 was included in this show and acquired by the Tate Gallery in 1980.

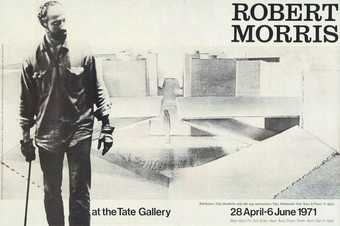

28 April – 6 June 1971

Exhibition poster for Robert Morris, Tate Gallery, 1971

Tate Public Records: Tate Gallery and Tate Britain Exhibition Posters: Robert Morris TG 106/152

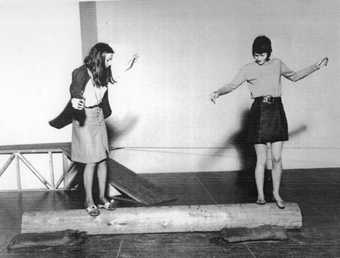

Visitors engaging with works in the Robert Morris exhibition at the Tate Gallery, 1971

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Robert Morris 1971

For his first solo exhibition in Britain, Robert Morris filled the length of the Tate Gallery’s sculpture hall with a series of interactive sculptures. It was the first show of this type in a major art museum. In the Evening Standard, the critic Richard Cork described the installation as ‘an aesthetic gymnasium’.15 The exhibition (mistakenly called ‘Action Sculpture’ in some quarters) was popular but following several injuries to members of the public it was closed after only four days on health and safety grounds and subsequently reopened as a more conventional exhibition.

In 2009 Tate curators worked with Morris to restage the exhibition at Tate Modern as Bodymotionspacethings in recognition of the significance of the exhibition as an early example of participatory art.

30 September – 7 November 1971

Installation shot showing Newton Harrison, Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece #3 1971 in 11 Los Angeles Artists, Hayward Gallery, London, 1971

© John Webb and Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre

Curated by Maurice Tuchman and Jane Livingston of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, this large exhibition built on shows such as West Coast Hard-Edge and the Tate Gallery’s Larry Bell / Robert Irwin / Doug Wheeler to provide the most expansive display of West Coast art yet seen in London. The exhibited artists were John Altoon, Larry Bell, Richard Diebenkorn, Newton Harrison, Maxwell Hendler, Robert Irwin, John McLaughlin, Bruce Nauman, Kenneth Price, Ed Ruscha and William Wegman.

In their catalogue essay Tuchman and Livingston noted that the show represented three separate generations of Los Angeles artists but was highly selective: major figures such as Sam Francis, Edward Kienholz (who had a large show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts the same year), John McCracken and James Turrell were missing.16 Tate purchased Larry Bell’s glass units Untitled 1971, which were made especially for the exhibition.

The exhibition generated controversy when Newton Harrison’s work Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece #3 was protested by the RSPCA and the poet Spike Milligan (who smashed a gallery window), leading to the temporary closure of the exhibition.17 As with the Robert Morris exhibition earlier that year, Tate had to engage with challenging questions about the art it was willing to show in relation to this show.

30 December – 6 January 1972

Jack Wendler Gallery opens in London with exhibition of work by Lawrence Weiner

Invitation card (exterior) to the opening of the Jack Wendler Gallery, London, 1971 with an inaugural exhibition by Lawrence Weiner

Tate Archive TGA 200911/2/16

Invitation card (interior) to the opening of the Jack Wendler Gallery, London, 1971 with an inaugural exhibition by Lawrence Weiner

Tate Archive TGA 200911/2/16

In October 1971 Jack Wendler, an American who was involved in conceptual art circles, moved from New York to London. The first exhibition at his new gallery was of the work of Lawrence Weiner, and the invitation to the opening took the form of a folded card by the artist.

Wendler’s short-lived London gallery at 164 North Gower Street focused on dematerialised art which could be created on location and did not require transportation. He presented John Baldessari’s first solo exhibition in Britain in April 1972, and early showings of American conceptual artists Robert Barry and Douglas Huebler.

1972

Tate acquires Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII 1966

Tate Gallery visitors viewing Carl Andre’s sculpture Equivalent VIII 1966

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: TG/PH/Andre/3

Artwork © Carl Andre / VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

Andre’s minimalist sculpture Equivalent VIII 1966 attracted little publicity when it was acquired by Tate in 1972, and again when exhibited in 1974 and 1975. However, an article in the Sunday Times about recent Tate acquisitions sparked a debate about the merits of the work, which consisted of a low stack of 120 firebricks.18 Other recent acquisitions highlighted by the writer included Claes Oldenburg’s Lipsticks in Piccadilly Circus, London 1966.

The Daily Mirror ran the story on its front page the following day with the headline ‘What a Load of Rubbish’, and other tabloids followed suit. Andre’s sculpture was put back on display soon afterwards but it was vandalised when a visitor threw blue vegetable dye onto the work. In 1978 the work was included in the artist’s most important British exhibition to date, Carl Andre: Sculpture 1959–1978 at the Whitechapel Gallery, and has been a regular feature of displays at Tate since.

1972

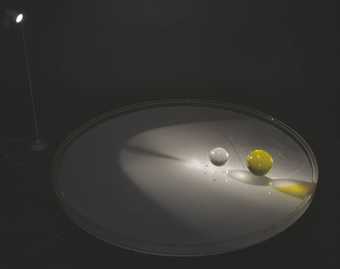

Liliane Lijn’s White Koan 1972 is installed on Armada Way, Plymouth

Liliane Lijn

White Koan 1972, installed outside the Warwick Arts Centre, Warwick

© Liliane Lijn

Liliana Lijn

Liquid Reflections 1968

Tate T01828

© Liliane Lijn

In 1972 the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation launched City Sculpture Projects. This led to the installation of fourteen public sculptures in the centre of eight cities in England and Wales for a six-month period. Among these was White Koan, a rotating conical sculpture illuminated at night, by the American artist Liliane Lijn who had moved to London in 1966.

None of the works were purchased, except White Koan, to the disappointment of the artists and organisers. The work was then exhibited in London and eventually purchased by the University of Warwick, where it was installed outside the Mead Art Gallery. The Tate Gallery went on to purchase Liquid Reflections 1968 in 1973 directly from the artist.

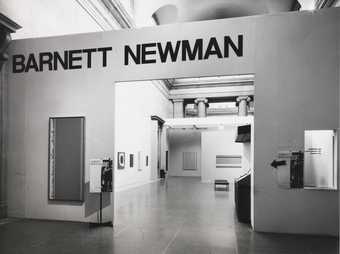

28 June – 6 August 1972

Barnett Newman

Tate Gallery

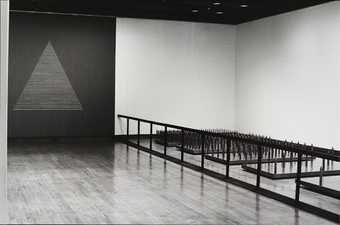

Installation view of the Barnett Newman exhibition at the Tate Gallery, London, 1972

Tate photographic collection location: TAPC list no.11, Tate Exhibitions, Barnett Newman (1905–70): Paintings and Prints, 28 June – 6 August 1972

Installation view of the Barnett Newman exhibition at the Tate Gallery, London, 1972

Tate photographic collection location: TAPC list no.11, Tate Exhibitions, Barnett Newman (1905–70): Paintings and Prints, 28 June – 6 August 1972

Barnett Newman

Adam 1951–2

Tate T01091

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Purchased in 1968 and included in the 1972 exhibition

Despite his renown, Barnett Newman (1905–70) did not have a solo exhibition outside America during his lifetime. Just before he died, however, he was engaged in discussions with the Tate Gallery about a show, which was also held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. As Tate Director Sir Norman Reid explained in his catalogue introduction, Newman was eager to exhibit at the Tate Gallery owing to his long friendship with the collector and Tate Trustee E.J. (Ted) Power, who had been one of Newman’s first collectors outside the US. The gallery had also become one of few institutions to purchase Newman’s work during the artist’s lifetime when it acquired Adam 1951–2 from the collector Ben Heller in 1968.

Critic Marina Vaizey noted that the exhibition was held at a time of ‘critical backlash’ against the American abstract artists of the post-war generation.19 Nonetheless, the critic John Russell came away from the exhibition ‘convinced all over again of two very important things: that abstract painting has as much to say to us as any other kind of painting, and that painting is above all a moral activity’.20 Of all the American painters of his generation, Newman had been perhaps the most admired by younger artists such as Frank Stella, and the critic Guy Brett summarised Newman’s distinctiveness, writing in his review that ‘in his desire to “begin again” Newman held out the longest. He rejected the most, and finally he came forward with the boldest and starkest expression of the new American painting’.21

29 March – 23 April 1973

Made in California

Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield

Cover of Made in California, exhibition catalogue, Mappin Gallery, Sheffield 1973

The introduction to the catalogue for this exhibition claimed that ‘an exhibition of contemporary American Art in Great Britain is something of a rarity, especially outside the premises of a few London dealers’.22 All but three of the fifty-three exhibits in this show were lent by the Felicity Samuel Gallery at 16 Saville Row, London, a gallery specialising in West Coast art.

The show was noteworthy for bringing the art of Ed Ruscha, Larry Bell and others to the north of England for the first time. It was also broader than its precursor, 11 Los Angeles Artists, including artists absent from the earlier exhibition, notably Billy Al Bengston.

Soon after the exhibition, the organiser of the exhibition, Graham W.J. Beal, moved to the United States, where his career included periods as director of the Los Angeles Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

4 April – 6 May 1973

Photo-Realism: Paintings, Sculpture and Prints from the Ludwig Collection and Others

Serpentine Gallery, London

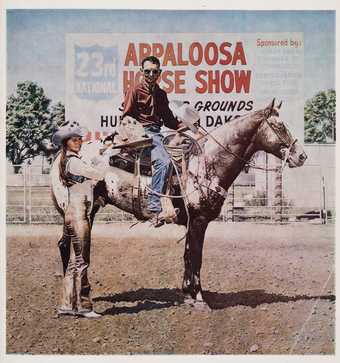

Cover of Photo-Realism: Paintings, Sculpture and Prints from the Ludwig Collection and Others, exhibition catalogue, Serpentine Gallery, London 1973, featuring Richard Mclean’s Rustler Charger 1971, mumok, Vienna / Austrian Ludwig Foundation © Richard McLean 2019

As Robin Campbell and Norbert Lynton noted in their preface, this exhibition, largely borrowed from the vast collection of German collector Dr Peter Ludwig, was the first in Britain to represent ‘the new realist trend in the United States’.23 It was also the first international exhibition held at the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens, a former tea-room which had opened as a gallery in 1970 with a focus on young British artists.

The artists in the show were John de Andrea, Robert Bechtle, Chuck Close, Robert Cottingham, Don Eddy, Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, Nancy Stevenson Graves, Duane Hanson, Howard Kanovitz, Richard McLean, Malcolm Morley and John Salt. The catalogue introduction was by the British critic Lawrence Alloway, then resident in the US.

On the whole, London critics were more enthusiastic about the gallery space than the exhibition, with the Guardian critic Caroline Tisdall reflecting the general consensus that photo-realism was ‘elaborate wasted effort’.24

1973

James Mayor takes over Mayor Gallery, London

Installation view of work by Agnes Martin on the Mayor Gallery stand at Art Basel 1974, the year that James Mayor took over the running of the gallery

London’s Mayor Gallery was founded by Fred Mayor in 1925 and was the first gallery to exhibit American sculptor Alexander Calder in Britain. When Fred Mayor’s son James took over in 1973, having set up the Post-War and Contemporary department at Sotheby’s New York, he quickly placed an emphasis on showing American artists. In 1973 and 1974 alone the gallery held solo shows of work by Andy Warhol (twice), Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Dennis Oppenheim, Roy Lichtenstein, Agnes Martin (at Art Basel), Man Ray, Eva Hesse and James Rosenquist, along with a group show, USA on Paper.

8–26 April 1974

c.7,500

Garage Gallery, London

Installation view of c.7,500, Garage Gallery, London, 1974

c.7,500, the last of the influential ‘Numbers Shows’ organised by the American writer and curator Lucy Lippard, was first shown at CalArts in Valencia, California, in 1973 before touring to several other venues in the US, and eventually to London. Here it was ‘hung, supervised and publicised by volunteers with minimal support from the Arts Council’.25 The exhibition included work by twenty-six women artists including Nancy Holt, Christine Kozlov and Adrian Piper, and was accompanied by a series of workshop discussions addressing topics raised by the exhibition.

Guardian critic Caroline Tisdall was scathing in her criticism of the exhibition, writing that it ‘stinks of the ghetto’ and that ‘the overall impression ... is of a long, tedious gripe related to a downtown shrink’.26 In a published response the art historian Griselda Pollock saw Tisdall’s review of the show as demonstrating ‘the male norm of culture’, and suggested Tisdall ‘should examine her strong reactions against it and ask why women's work should provoke such hostility in the context of the art world in which she practices as a critic’.27 Lippard’s work in London during this period also included the 1980 exhibition Issue.

29 May – 13 July 1975

The Condition of Sculpture: A Selection of Recent Sculpture by Younger British and Foreign Artists

Hayward Gallery, London

Installation view showing Larry Bell, Untitled 1971–2 (right) and David Evison, Number Six 1975 in The Condition of Sculpture: A Selection of Recent Sculpture by Younger British and Foreign Artists, Hayward Gallery, London, 1975

© Heini Schneebeli and Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre

The sculptor William Tucker, who had proposed this exhibition, insisted in his catalogue introduction that ‘this is an exhibition of sculpture, not of sculptors. Nor is the exhibition either polemic or programmatic in intent’.28 Several American sculptors were included, notably Carl Andre, Larry Bell (familiar to London audiences by this point), and Richard Serra (less familiar).

The show, and particularly Tucker’s catalogue introduction, attracted substantial criticism within the mainstream media, though a number of critics singled out works by American artists as among the best in the exhibition. Marina Vaizey, for instance, wrote that ‘Mark di Suvero’s remarkable steel creature [Untitled 1974] is both aggressor and sentinel’.29 William Packer applauded Bell’s ‘lovely glass structure’.30 Caroline Tisdall in the Guardian included Andre and Serra among the artists ‘whose feel for their materials is more central to their work than formal jugglings’ but lamented, ‘It’s sad to see the artist, with his open brief, so blinkered to the rest of the world’.31

18 September – 31 October 1976

Walker Evans: Photographs

Museum of Modern Art, Oxford

Installation view of Walker Evans: Photographs at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1976

© Modern Art Oxford

John Szarkowski, Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, selected the works for this circulating exhibition organised by the museum’s International Council. The show comprised eighty photographs, mostly of Evans’s work for the Farm Security Administration immediately before and during the Second World War, drawn from the holdings of MoMA and the Walker Evans estate.

Guardian critic Caroline Tisdall saw Evans’s career as epitomising the development of the USA in the twentieth century. According to her, Evans ‘captured the old austere spirit more succinctly than any other realist photographer’ but his later work photographs looked ‘more like symbols of America fossilised in furniture than records of life’.32 At the same time the Institute of Contemporary Arts showed Images of an Era: The American Poster 1945–1975, organised by the Smithsonian Institution, about which Tisdall wrote, ‘it’s as paradoxical as the country itself: social concern rubbing shoulders with frontal opportunism, and all under the auspices of Mobil Oil’.33

23 September – 16 October 1976

Mary Kelly: Post-Partum Document

Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Mary Kelly

Post-Partum Documentation III: Analysed Markings and Diary Perspective Schema (Experimentum Mentis III: Weaning from the Dyad) 1974

Tate T03925

© Mary Kelly

The American artist Mary Kelly moved to England to undertake postgraduate study at St. Martin’s School of Art. Post-Partum Document 1973–9, an exploration of the mother-child relationship over six years, consists of six sections, the first of which was shown at the Northern Arts Gallery, Newcastle, in 1975. Parts I–III of the work were first shown together at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, where the stained nappy liners included as documentation of Kelly’s relationship with her child provoked tabloid outrage.

A seminar titled ‘Psychoanalysis and Feminism’ was organised during the exhibition, indicating the relevance to the work of Juliet Mitchell’s 1974 book of the same title.

While Kelly had participated in various collaborative projects during the 1970s, this was her first British solo exhibition. It was followed by a show at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, in 1977.

1976

Nicholas Serota is appointed director of Whitechapel Gallery, London

From 1976 to 1988, under the directorship of Nicholas Serota the Whitechapel Gallery held a number of important shows of American artists, including the first British exhibition of work by Robert Smithson (18 May – 26 June 1977) and solo shows of Robert Ryman (21 September – 23 October 1977), Carl Andre (17 March – 23 April 1978), Joan Jonas (9–16 February 1979) and Eva Hesse (4 May – 17 June 1979).

10 May – 18 June 1977

Jubilation: American Art during the Reign of Elizabeth II

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

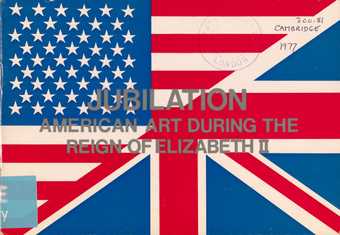

Cover of Jubilation: American Art during the Reign of Elizabeth II, exhibition catalogue, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge 1977

Michael Jaffé, director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, declared this exhibition ‘a special, unprecedented treat for Cambridge’.34 With the exception of Jasper Johns’s painting Target 1958 (which was lent by the artist), all works in the exhibition were drawn from British galleries (such as Mayor and Kasmin) and private collectors. Jubilation was one of the earliest exhibitions to show the work of Vito Acconci in Britain.

6–26 July 1980

American Art at Home in Britain: The Last Four Decades

American Embassy, London

Installation view of American Art at Home in Britain: The Last Four Decades, American Embassy, London, 1980; on the wall (left-to-right) Robert Rauschenberg, Bait 1963; Franz Kline, Untitled 1959; Willem de Kooning, Woman-Torso 1965–6; on floor Carl Andre, Sorts 1972

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: American Art at Home in Britain: The Last Four Decades 1980

Installation view of American Art at Home in Britain: The Last Four Decades, American Embassy, London, 1980

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: American Art at Home in Britain: The Last Four Decades 1980

In his catalogue foreword, USIS Cultural Affairs Officer Irving Sablosky emphasised the value of this exhibition as a succinct overview of post-war American art. Perhaps more significant, however, was the fact that the works in the exhibition, organised to coincide with Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee, were drawn exclusively from the collections of members of the Contemporary Art Society, a charity founded in 1910 to purchase and donate works of art to British museums and galleries. Thus, unlike many earlier exhibitions, which were organised by or drawn from the collections of American institutions, notably the Museum of Modern Art in New York, American Art at Home in Britain showed the growing strength of holdings of American art among British collectors.

8 May – 22 June 1980

Pier + Ocean: Construction in the Art of the Seventies

Hayward Gallery, London

Installation view showing Walter De Maria, Bed of Spikes 1968–9 in Pier + Ocean: Construction in the Art of the Seventies, Hayward Gallery, London, 1980

© Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre

Taking its title from the ‘pier and ocean’ paintings of the Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian, this exhibition, selected by the artist Norman Dilworth and curator Gerhard von Graevenitz, was divided into three sections: ‘Concepts of Space’, ‘Chance System Endlessness’ and ‘Gravity’.

The American artists represented in the exhibition were Carl Andre, John Baldessari, Bill Beckley, Walter De Maria, Douglas Huebler, Will Insley, Donald Judd, Sol Lewitt, Bruce Nauman, George Rickey, Ed Ruscha, Fred Sandback, Richard Serra, Joel Shapiro, Charles Simonds, Robert Smithson, Kenneth Snelson, Richard Tuttle, William Wegman and Lawrence Weiner. The exhibition toured to the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, in the Netherlands.

Later director of the Camden Arts Centre, Jenni Lomax recalled that the exhibition ‘pulled aspects of contemporary British and American art towards Northern Europe, making connections that were both revealing and liberating’.35

14 November – 21 December 1980

Issue: Social Strategies by Women Artists

Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

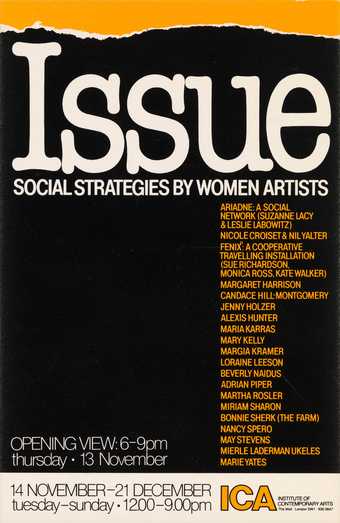

Cover of Issue: Social Strategies by Women Artists, exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1980

Lucy Lippard, the exhibition’s organiser, described this as ‘the first establishment-approved women’s show in London’.36 She conceived it as ‘a framework for a transatlantic and cross-cultural dialogue’ about feminist art practice, and responses to various issues including ecology, unemployment, war and violence against women.

The exhibition included many American women artists, including: Ariadne: A Social Art Network (Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz), Candace Hill-Montgomery, Jenny Holzer, Maria Karras, Mary Kelly, Margia Kramer, Beverly Naidus, Adrian Piper, Martha Rosler, Bonnie Sherk, Nancy Spero, May Stevens and Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Kelly, an American artist resident in England for many years, sensed that ‘in most of the work by American artists ... any emphasis on the “personal” appeared to detract from what they would consider “wider social issues”’.37 In this she distinguished it from European feminist work in which ‘the social and the psychic haven't been seen as necessarily antagonistic or contradictory’.

The exhibition toured to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland Gallery in Belfast in 1981.