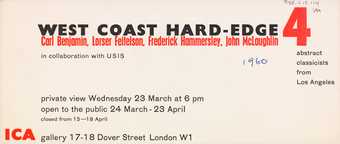

24 March – 14 April 1960

West Coast Hard-Edge: Four Abstract Classicists from Los Angeles

Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Invitation to the private view of West Coast Hard-Edge: Four Abstract Classicists, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1960

Tate Archive TGA 955/1/12/114

The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) regularly exhibited recent American art in the late 1950s and 1960s. In 1959, for example, it held shows of the work of Man Ray and Adolph Gottlieb. Organised with the United States Information Service, West Coast Hard-Edge included works by Karl Benjamin, Lorser Feitelson, Frederick Hammersley and John McLaughlin. A revised version of Four Abstract Classicists, curated by Jules Langsner and first shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, it was notable for its foregrounding of ‘hard-edge’ painting and emphasis on West Coast artists, foreshadowing other exhibitions in London later in the decade. Shortly afterwards, Morris Louis: Recent Painting, also at the ICA (18 May – 4 June 1960) allowed British audiences to see Louis’s work for the first time.

The ICA’s endorsement of American art very much reflected the interests of Lawrence Alloway who served as the Institute’s Deputy Director from 1957 to 1961. Alloway subsequently moved to the US, taking up a short-lived curatorial position at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in January 1962 before becoming an academic and prominent critic.

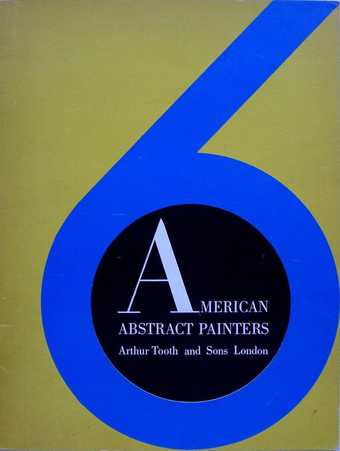

24 January – 18 February 1961

6 American Abstract Painters

Arthur Tooth and Sons, London

Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition 6 American Abstract Painters at Arthur Tooth and Sons Gallery, London 1961

This was the second exhibition of hard-edge painting in Britain after the 1960 West Coast Hard-Edge at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. In his review the critic Roger Coleman emphasised the differences between the six artists in the exhibition (Ellsworth Kelly, Alexander Liberman, Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt, Leon Smith and Sidney Wolfson). Coleman saw this variety as evidence that hard-edge amounted to more than merely ‘a hardening … of the Rothko arteries … in a search for something new’.1 Kelly had a one-man exhibition at Tooth’s the following year.

All six exhibiting artists were represented by Betty Parsons, whose gallery in New York held seminal exhibitions by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and Barnett Newman early in their careers. 6 American Abstract Painters featured a catalogue text by Lawrence Alloway, a leading British commentator on American abstract painting.

For information about Ad Reinhardt’s involvement in the exhibition and presence in the UK, see Moran Sheleg’s essay ‘An “Outcast“ Abroad: Ad Reinhardt in London’.

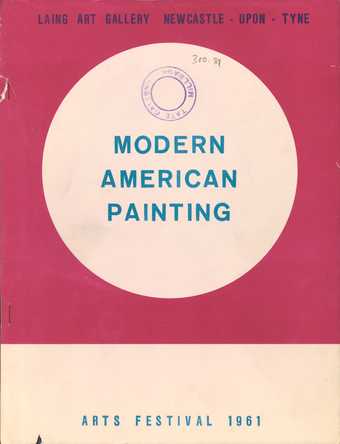

April – May 1961

Modern American Painting

Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle

Cover of Modern American Painting, exhibition catalogue, Laing Gallery, Newcastle 1961

Ray Parker

Untitled 1959

Tate T00441

© reserved

In the catalogue introduction critic Lawrence Alloway noted that while ‘no well-attended exhibition of American painting was seen in London until 1956 ... that the United States Information Service can now, in 1961, present this exhibition drawn wholly from English sources, shows how recognition of the American post-war achievement in art has spread’.2 Artists exhibited ranged from Mark Tobey and the ‘1903 – 1913 generation’ (in Alloway’s words) of first-generation abstract expressionists, to younger artists including Helen Frankenthaler and Jim Dine. Ray Parker’s painting Untitled 1959, included in the exhibition, was purchased by the Tate Gallery in the same year.

The exhibition was organised as the Laing Art Gallery’s contribution to Newcastle’s first arts festival, in collaboration with the American Embassy in London, where it was subsequently shown.

October – November 1961

New New York Scene

Marlborough New London Gallery, London

Lee Bontecou

Untitled 1961

Tate T00506

© Lee Bontecou

Marlborough Fine Art in London held a Jackson Pollock exhibition in June 1961, and followed up with this show at its recently established New London Gallery, situated a stone’s throw further north on Old Bond Street. New New York Scene included artists such as Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, who typified the new tendency for stained fields of colour.

Ironically, the exhibition indicated the direction that the gallery’s former director John Kasmin, who had left in the summer of 1961, was to take when opening his own gallery in 1963.3

This exhibition was also the first in Britain to show the work of Lee Bontecou, whose drawing Untitled 1961 was presented to the Tate Gallery by Leo Castelli in the following year. The exhibition was organised in association with David Gibbs.

December 1961

Tate Gallery acquires Jasper Johns’s painting 0 through 9 1961

Jasper Johns

0 through 9 1961

Tate T00454

© Jasper Johns

The work of Jasper Johns (born 1930) was first seen in Britain when White Numbers 1958 was exhibited in the group exhibition The Mysterious Sign (Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 23 October – 3 December 1960). The acquisition by the Tate Gallery of 0 Through 9 was unusually early in the career of an American artist, although Lee Bontecou (born 1931) was of a similar age when one of her drawings entered the collection in 1962.

Johns had to wait another three years for his first solo exhibition in the UK. The critic David Sylvester concluded a 1964 broadcast on the artist by comparing him with Picasso and Braque, and declaring: ‘at 30 one can be a master. I believe Johns is one’.4

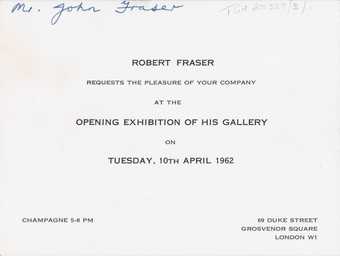

10 April 1962

Opening of Robert Fraser Gallery, London

Invitation to the opening of the Robert Fraser Gallery on 10 April 1962

Tate Archive TGA 200329/3/1

The gallerist Robert Fraser spent time working in New York, where he befriended a number of artists including Jim Dine and Ellsworth Kelly, before returning to London to open a gallery. His gallery held a number of important exhibitions of American artists, including: John Chamberlain and Richard Stankiewicz (14 May – 8 June 1963); Bruce Conner (16 December 1964 – 9 January 1965); Jim Dine (June 1965), from which Tate acquired Dine’s painting Walking Dream with a Four Foot Clamp 1965; Los Angeles Now (26 January – 19 February 1966), including works by Ed Ruscha, Dennis Hopper, Larry Bell, Wallace Berman, Jess Collins, Bruce Conner, Llyn Foulkes and Craig Kauffman; Jim Dine (13 September – 15 October 1966); Claes Oldenburg (22 November 1966 – 15 January 1967); and The American Scene (8 August – 30 September 1967), including works by Dine, Roy Lichtenstein, Oldenburg and Andy Warhol.

May 1962

Rivers

Gimpel Fils, London

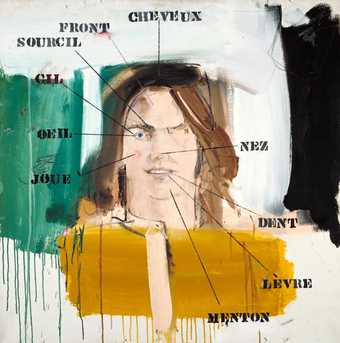

Larry Rivers

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961

Tate T00522

© The estate of Larry Rivers

In 1962 the Mayfair gallery Gimpel Fils began to place increasing emphasis on American art, starting with the exhibition A Selection of East Coast and West Coast American Painters (March 1962). This was followed by the first British exhibition of Larry Rivers, then living in Paris. Rivers had visited England the previous year, when he lectured at the Ealing School of Art.

The catalogue included texts by poet John Ashbery and Art News editor Thomas B. Hess, who proclaimed Rivers ‘one of the leaders of the second wave of New York school painting’.5 Rivers’s playful figurative art generated substantial interest as part of the movement towards a ‘return to the image’, although its spontaneity owed as much to abstract expressionism as to pop art.

Rivers’s 1962 Gimpel Fils exhibition included Parts of the Body: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961, which was purchased that year by the Tate Gallery.

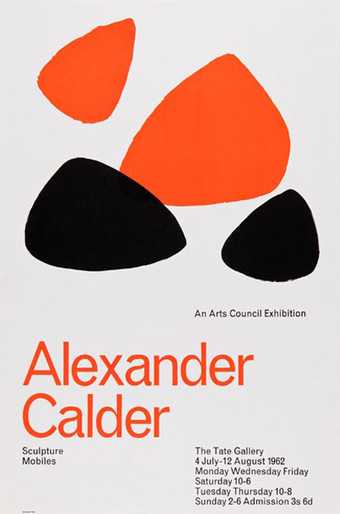

4 July – 12 August 1962

Alexander Calder: Sculpture, Mobiles

Tate Gallery

Poster for Alexander Calder: Sculpture, Mobiles, Tate Gallery, 1962

Tate Archive TG 92/169

© ARS, NY and DACS

Alexander Calder first exhibited in Britain at the Mayor Gallery in London in 1937, and thereafter exhibited regularly during the 1950s at the Lefevre Gallery, also in London.

The idea for a Calder exhibition was suggested by the artist and Tate Trustee John Piper in 1960.6 Organised by the curator and writer James Johnson Sweeney, the 1962 retrospective was the first time that much of Calder’s larger work could be seen in the United Kingdom. Critics enthusiastically recommended the Tate exhibition as an antidote to ‘difficult’ modern art. The Times art critic saw it as proof that art ‘can make the spirit dance and sing and laugh’, and observed that Calder’s work had ‘never made the Tate’s great vaulted halls look more airy’.7

When the artist Bridget Riley visited the exhibition, she complained that Calder’s work was rather too popular with Tate visitors: ‘I was absolutely horrified to see the attendants setting an example by touching the mobiles obviously in order to demonstrate the movement – this resulted in the public touching, banging and hitting these works in an unbelievable manner.’8 In all, the exhibition attracted 14,479 visitors.9

25 September – 20 October 1962

Milton Avery: Exhibition of Paintings

Waddington Galleries, London

Milton AveryYellow Sky 1958Tate T00575© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

The Waddington Galleries began showing American artists in the early 1960s, notably Richard Diebenkorn and ‘colour field’ painters such as Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland and Helen Frankenthaler, and the figurative artist Milton Avery. Isolated examples of Avery’s work had been seen in group shows before, but this was the first British one-man exhibition of his landscapes and figure studies. These were lauded by critics, one of whom began his review by writing, ‘to walk into the Waddington Galleries, 2, Cork Street, this month is to feel an immediate lift of the heart, an easeful enjoyment of visual beauty’.

A 1957 essay by Clement Greenberg was reprinted in the catalogue, in which the American critic predicted an end to the ‘unexportability’ that had seen Avery receive little attention outside the US for much of his career. Greenberg believed that: ‘there are certain seascapes Avery painted in Provincetown in the summers of 1957 and 1958 that I would expect to stand out in Paris, or Rome or London just as much as they do in New York’.10

The year after this exhibition, Tate acquired Avery’s Yellow Sky 1958 as a gift through the American Federation of Arts. The painting had featured in an Avery retrospective organised by the Whitney Museum but not in the Waddington Galleries show.

1962

The Tate Gallery acquires Black Wall 1959 by Louise Nevelson

Louise Nevelson

Black Wall 1959

Tate T00514

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Louise Nevelson rose rapidly to international prominence in the late 1950s and early 1960s. A colourful personality, she was the subject of a feature in Life magazine in 1958, and won the sculpture prize at the Art USA 1959 exhibition at the New York Coliseum and shared the Art Institute of Chicago’s Logan Medal with fellow New York sculptor Isamu Noguchi. In 1962 she was announced as the US representative for that year’s Venice Biennale.

Tate Director Sir Norman Reid identified Nevelson as a priority for acquisition in late 1961 following a trip to the US, and the gallery was able to secure Black Wall from the artist when it was exhibited at the Hanover Gallery in London.11 In response to a letter about the work from Ronald Alley, Keeper of the Modern Collection, Nevelson wrote in characteristically mystic and inscrutable language:

My black wall in the Tate collection was indeed the first finished wall. However, in answer to your question concerning my original intention and whether or not the stacking of the boxes was an afterthought, I am compelled to tell you that I do not think in afterthoughts.

I am cloaked in psychic phenomena so how can I answer your question? My creative life is creative energy plus physical energy: our question is primate and factual – a mathematical problem. I appreciate your concern but I cannot answer your question.12

15 February – 17 March 1963

Art: USA: Now

Royal Academy of Arts, London

This exhibition showcased the collection of contemporary American paintings belonging to Herbert Fiske Johnson, chairman of American company S.C. Johnson & Son (commonly known as Johnson Wax), and his wife Irene Purcell Johnson, assembled at a cost of around $750,000. Johnson purchased recent works by 102 American artists and exhibited them internationally before donating the collection to the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., in 1966.13

Lee Nordness, the gallerist who organised the tour, wrote that the exhibition was distinguished from other recent shows of American art by its breadth, although it favoured well-established artists: ‘Since World War II many countries have expressed interest in American art, and while a number of exhibitions have been sent abroad, few have been surveys and none has been broad enough to indicate all the existing schools. ART: USA: NOW should provide an opportunity for the artists and public of the world to see the widest range of American painting’.14

Unsurprisingly, several significant artists were absent from the collection (including Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman and Helen Frankenthaler). The exhibition strained to balance abstract and figurative painting, with the Times critic writing of the hanging ‘alternating between the two with every picture’.15 The same critic felt that, given the dominance of abstract painting in post-war America, the collection tended ‘to obscure essential issues by falling over backwards to be fair’. An alternative view was offered by Edward Lucie-Smith in the Listener, who wrote that while the abstract artists were mostly familiar to the British public, the exhibition was ‘worth visiting for the insight it gives into American realist art’.16

May – September 1963

Sculpture: Open-air Exhibition of Contemporary British and American Works

Battersea Park, London

David Smith

Cubi IX 1963

Walker Art Center

© David Smith Estate/VAGA, New York, NY

Open-air sculpture exhibitions were held regularly at Battersea Park in the post-war period. The distinctive feature of this particular exhibition was a strong presence of American art, with work by twenty US sculptors – including John Chamberlain, David Smith and Richard Stankiewicz – selected by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The show gave the public a rare opportunity to view American sculpture in an open-air setting, as well as to compare recent British and American sculpture. The critic Nigel Gosling in the Observer approved of the installation, noting how ‘David Smith’s nine shimmering steel cubes [Cubi IX] serenely mirror the lake beside which they stand’. Gosling wrote that ‘the American contribution is more sophisticated and urban than our own’, noting a tendency to ‘explore the intricate gothic space-patterns formed by machinery or metal scrap’.17

18 April – May 1963

Photograph of the façade of Kasmin Gallery, 1971–2

Tate Archive Photographic Collection

Photograph of John Kasmin at the desk in his gallery during an exhibition of paintings by Kenneth Noland in 1967

Artwork © Kenneth Noland

Photo © David Hockney

Kasmin Ltd, run between 1963 and 1973 by the former Marlborough New London Gallery director John Kasmin, was the main British outpost for American post-painterly abstraction, exhibiting the work of such artists as Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Larry Poons and Frank Stella. In his exhibitions of British artists Kasmin’s taste ranged widely, and he also exhibited Indian miniatures, but with American art he focused on a specific type of practice. According to the critic David Sylvester, Kasmin selected only those artists who had the critic ‘Clement Greenberg’s seal of approval or some hope of being granted it’.18 Greenberg was strongly associated with ‘colour field’ painting in the 1960s, as opposed to pop art or other tendencies.

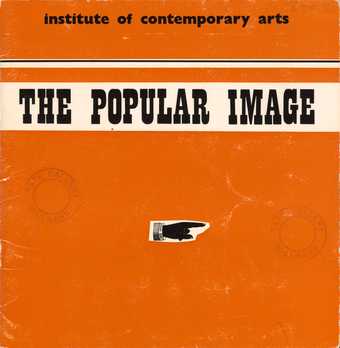

23 October – 23 November 1963

Cover of Popular Image USA, exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1963

Organised by the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in collaboration with the Ileana Sonnabend Gallery, Paris, Popular Image USA was the first comprehensive exhibition of American pop art in Britain. Jasper Johns’s work was singled out for particular praise.

Summing up responses to the exhibition, the ICA’s director Julie Lawson wrote to Sonnabend: ‘reactions from visitors are rather mixed – either they rave about it or don't care for it. But even those who don’t like it personally consider it interesting’.19 Observer critic Nigel Gosling reflected the divisiveness of the exhibition, writing that it ‘presents us for the first time with a peep at the American pioneers of what in this country became known as Pop Art, and it is a disturbing sight’.20

The artists exhibited were: Allan D’Arcangelo, Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Mel Ramos, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Wayne Thiebaud, Andy Warhol, John Wesley and Tom Wesselman.

15 November – 22 December 1963

Dunn International

Tate Gallery

Sam Francis

Around the Blues 1957, 1962–3

Tate T00634

© Estate of Sam Francis/ARS, NY & DACS, London

The Dunn International exhibition, first shown at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, Canada, took its name from its sponsor, the Sir James Dunn Foundation. It claimed to include ‘a key work by virtually every living artist of fame and promise’.21

The Tate Gallery exhibition was organised by British art historian and reviewer John Richardson, and a three-man jury awarded six prizes of $5,000 to exhibited works. Winning artists included the Americans Ivan Albright (Poor Room c.1952–62) and Sam Francis (Around the Blues 1957, 1962–3, which the Tate Gallery purchased from the artist in the following year). Other Americans exhibited were: Edwin Dickinson, Richard Diebenkorn, Leon Golub, Adolph Gottlieb, Morris Graves, Edward Hopper, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, R.B. Kitaj, Willem de Kooning, Jack Levine, Loren Maciver, Conrad Marca-Relli, James McGarrell, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, James Rosenquist, Ben Shahn, Mark Tobey and Andrew Wyeth.

4 February – 8 March 1964

Installation view of Robert Rauschenberg's exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, from 4 February to 8 March 1964

Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, Whitechapel Gallery Archive

Part of the important series of shows by American artists organised at the Whitechapel Gallery by Bryan Robertson, this exhibition took place shortly before Rauschenberg was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. In the catalogue preface Robertson explained that Rauschenberg was an important influence ‘for young artists especially, because they are on his wave-length, they speak his language, and although they do not always share his American experience they understand his references’.22 The critical response to the exhibition was almost unanimously enthusiastic, with Guy Burn in Arts Review concluding that Rauschenberg represented ‘a revolution against established modern art, as when Picasso painted the Demoiselles d’Avignon’.23

The exhibition included Rauschenberg’s series of thirty-four Dante Drawings 1959–60 (one for each Canto of Dante’s Inferno), which the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA) had acquired in 1963. After forming part of the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition, the Dante Drawings travelled to nineteen further venues in an extensive European tour organised by MoMA’s International Council. This included four more venues in Britain: the USIS Gallery, London; Hatton Gallery, Newcastle; the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; and the Arts Council Gallery, Cambridge.24

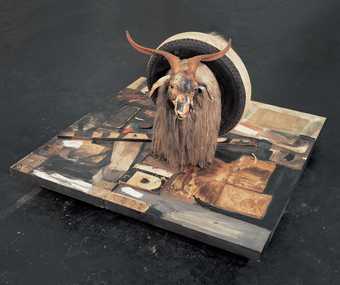

22 April – 28 June 1964

Installation view of 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, Tate Gallery, London, 1964

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade 1964

Robert Rauschenberg

Monogram 1955–9

Moderna Museet, Stockholm

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Comprising 354 works, this exhibition looked back at art over the last decade. According to the catalogue, this exhibition was ‘chiefly concerned with kinds of painting and sculpture that have seemed to increasing numbers of people in many countries to be particularly characteristic of these years’.25

Installed within a ‘maze of screens and lights’ designed by architects Alison and Peter Smithson, the show included a large proportion of Americans (both of the first abstract expressionist generation and younger pop and abstract artists), as well as artists mostly working in London and Paris.26

Critic John Russell in the Sunday Times detected a particular admiration among the organisers for American art, writing, ‘we may take it ... as a mark of affection for a New-Found Land that Stuart Davis, [Robert] Rauschenberg and [Jasper] Johns are treated in the catalogue with a deference accorded to none of the Europeans in the show’.27 Some were awestruck: the critic Edward Lucie-Smith highlighted Rauschenberg’s Monogram 1955–9 in his review, writing, ‘One goes deliberately to see it, hoping for some kind of transformation in oneself’, and praising Rauschenberg for ‘gambling for high stakes’.28

In her essay in this publication, Moran Sheleg writes:

Although marred by a ‘harrowing … hang’, an error-filled catalogue that needed reprinting and regrettable damage to some artworks, the show prompted some fundamental questions. Foremost amongst these was what shape the recent past and immediate present was taking in art, and who exactly was doing the shaping … Although the display began with works by Picasso and Matisse, many critics noted that there seemed to be an unfair ‘bias’ towards recent work made by young American – and to a certain extent British – painters with little room left for that of their elder – and French – counterparts.

27 May – 27 June 1964

Ad Reinhardt

Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Installation view of the exhibition Ad Reinhardt, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1964

© 2019 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Reinhardt’s modest but intense display of his recent square canvases at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) offered a stark contrast to the mood and approach of the concurrent 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade at the Tate Gallery, in which examples of his earlier work featured. Owing to the ICA’s limited resources, the artist had to pay for the transport of his works himself, and to help garner publicity for the show gave a lecture in which he described himself as an outcast from the contemporary art scene.

In her essay in this publication Moran Sheleg shows that the presentation of Reinhardt’s works was generally well received. According to Sheleg, the exhibition tested the views of some – exemplified by her quotation of the critic and novelist Anita Brookner in the Burlington Magazine – that abstract geometric painting was ‘now little more than “one failed strain of the school of Paris”, which was being further degraded by its American successors either through “active plagiarism” or thinly-veiled pastiche’.29

8 June 1964

Carolee Schneemann performs Meat Joy at Dennison Hall, London

Carolee Schneemann

Still from Meat Joy 1964

© Carolee Schneemann

Marking an important moment in the early history of performance art, Carolee Schneemann first performed her work Meat Joy at the Festival de la Libre Expression in Paris on 29 May 1964, bringing it to London shortly afterwards. She later said of this piece for four men and four women, ‘Meat Joy has the character of an erotic rite: excessive, indulgent, a celebration of flesh as material: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, transparent plastic, rope, brushes, paper scrap’.30

Her subsequent work in London included a kinetic theatre performance in 1967 at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress, an international conference whose participants included Stokely Carmichael, Allen Ginsberg, Lucien Goldmann, R.D. Laing and Herbert Marcuse.

July – August 1964

Merce Cunningham Dance Company and Robert Rauschenberg in Britain

John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg (left to right), London, 1964

© Douglas H. Jeffery / Victoria and Albert Museum London

Cunningham’s company undertook a world tour in 1964, which included a stay of several weeks in Britain performing at Dartington College of Arts in Devon and, in London, at Sadler’s Wells Theatre and the Phoenix Theatre. The audience for the company’s performances included many artists and art students attracted by the participation of the artist Robert Rauschenberg who contributed set, costume and lighting designs.

An exhibition of Rauschenberg’s work had taken place at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, earlier in the year (Whitechapel Gallery director Bryan Robertson had regretted the absence of Rauschenberg’s work with Cunningham from the exhibition).31 Rauschenberg’s reputation was further elevated when he won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in June 1964.32 In one of the London performances Rauschenberg created onstage a combine (a work blending painting, sculpture and assemblage of found objects), titled Sorry.33

To coincide with the London performances, an exhibition of photographs of Cunningham’s company by Jack Mitchell was held at the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square.

2 April – 2 May 1965

Arshile Gorky: Paintings and Drawings

Tate Gallery

Arshile Gorky

Waterfall 1943

Tate T01319

© ADAGP Paris and DACS, London

The work of Arshile Gorky (1904–48) was included in the touring exhibitions Modern Art in the United States and The New American Painting, as well as a 1964 exhibition of The Peggy Guggenheim Collection (all at the Tate Gallery). This 1965 show, however, was the first full retrospective of his work in Britain. His paintings had never been seen in Britain while he was alive, and in the introduction to the exhibition catalogue the critic Robert Melville remarked on the discrepancy between the significance of Gorky’s work and its lack of international exposure during his lifetime: ‘Gorky made the first major American contribution to twentieth-century painting, yet before his death in 1948 I came across his name, so conspicuously un-American, only in a gallery announcement in the New York magazine View’.34

Waterfall 1943 was included in the Tate retrospective, and it remained on loan at the gallery from the artist’s estate until it was formally acquired in 1971.

14 July – 18 August 1965

Six Decades of American Art

Leicester Galleries, London

Ben Shahn

Lute and Molecules 1958

Tate T00314

© Estate of Ben Shahn / VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

This exhibition was organised in association with the Downtown Gallery, New York, founded by Edith Halpert in 1926, and showcased works from her collection by twenty-two modern American artists including Stuart Davis, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe and Ben Shahn.

The catalogue introduction was written by Bryan Robertson, director of the Whitechapel Gallery, who believed the exhibition to be ‘of special consequence and long overdue in London’ given that ‘in England, there is still a slight danger of the layman assuming that American art as we know it began with Pollock, Rothko, de Kooning, Newman, and one or two others in the 1940s’.35

Robertson also used his introduction to criticise the purchasing policy of the Tate Gallery with regard to this generation of American artists, although by this time works by Shahn and Marin were in the Tate collection. Shahn’s screenprint Lute and Molecules 1958 was acquired from the Leicester Galleries after it was included in an exhibition of Shahn’s graphic work in 1959, while Marin’s watercolour Downtown, New York 1923 was purchased from the Downtown Gallery, New York, in 1956.

November 1965

Peter Townsend becomes editor of Studio International

Cover of Studio International, January 1966

Under the editorship of Peter Townsend (1919–2006), Studio International (founded as The Studio in 1893 and renamed in 1964) became a crucial platform for discussion of contemporary international, and particularly American, art. In 1969, for example, the magazine published Joseph Kosuth’s important essay ‘Art After Philosophy’. The magazine also presented new work in innovative ways: the July – August 1970 issue was an exhibition in magazine form, curated by Seth Siegelaub and other international critics.

Townsend left the magazine in 1975 and soon after co-founded Art Monthly with Jack Wendler.

18 August – 25 September 1966

David Smith 1906–1965

Tate Gallery

Sculptures by David Smith outside the Tate Gallery during the exhibition David Smith 1906–1965, Tate Gallery, London, 1966

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: David Smith 1906–1965, 1966

As with many major American artists of his generation, David Smith’s work was not shown extensively in Britain until after his death. Waldo Rasmussen, director of Circulating Exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, wrote the preface to the exhibition catalogue, which began by describing the show’s context:

The present exhibition of David Smith’s sculpture had been planned with the artist for over two years before his tragic death in May 1965. David Smith was a man of great pride and energy, and he looked upon a European tour of his work as both an honour and a challenge. He was enormously pleased and gratified by the invitation of the Tate Gallery to present his work in London, and the prospect of the exhibition was a great stimulus to him. It was to be his first opportunity to show a large body of his work in Europe.36

The exhibition favoured Smith’s late works such as the Cubi and Voltron series of sculptures, with half of the works in the exhibition having been produced in the last five years of the artist’s life. Critic John Russell in the Sunday Times noted that many aspects of Smith’s work were not represented but concluded that nonetheless the show produced ‘an irresistible effect of exhilaration and generosity and manifold fulfilment’.37

13 September – 15 October 1966

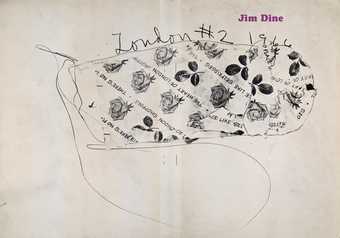

Cover of Jim Dine: London 1966, exhibition catalogue, Robert Fraser Gallery, London 1966

The Robert Fraser Gallery in London was prosecuted and fined for holding this exhibition of Dine’s works. A few days after the opening of this exhibition of works on paper, police removed several of the exhibits with a warrant issued under the Obscene Publications Act. The works were subsequently ruled to be indecent, though not obscene.

In advance of the trial Fraser enlisted as potential expert witnesses the Whitechapel Gallery director Bryan Robertson, artist Roland Penrose and critic David Sylvester. As Sylvester recalled: ‘the only one of us to be called was Robertson. He proceeded to give a speech which was stunning in its authority and lucidity, a quiet, patient, courteous, relentless demolition of philistinism. It turned the occasion into a moral victory. I don’t know what effect it had on the judgment: the gallery was fined 20 guineas and ordered to pay 20 guineas costs’.38

1966

Tate Gallery acquires Roy Lichtenstein’s painting Whaam! 1963

Roy Lichtenstein

Whaam! 1963

Tate T00897

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Painted in 1963, Whaam! had already been shown in several prestigious international exhibitions before it was acquired by the Tate Gallery from the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1966. Tate went on to stage a Lichtenstein show in 1968. In the catalogue, Director Norman Reid claimed that this acquisition ‘aroused more public interest than almost any purchase since the war’.39

The painting is one of a series of ‘war paintings’ Lichtenstein made in 1962–3, and was based on an image from the comic All-American Men of War published by DC Comics in 1962.

29 October – 19 November 1966

American Painting and Sculpture

Midland Group Gallery, Nottingham

Cover of American Painting and Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Midland Group Gallery, Nottingham 1966

During the 1960s the Midland Group (1943–87), an important organisation for the presentation of new art in Nottingham, staged increasingly ambitious exhibitions of international art at its gallery on East Circus Street. One of the first of these was American Painting and Sculpture, which included works lent by gallerists such as John Kasmin as well as by the art dealer Peter Cochrane (1913–2004), by artists including Alexander Calder, Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol.

Another significant exhibition was Visions, Projects, Proposals (11 July – 2 August 1970), which included a wall drawing by Sol Lewitt along with documentation of Robert Smithson’s famous earthwork Spiral Jetty 1970, constructed only a few months earlier.

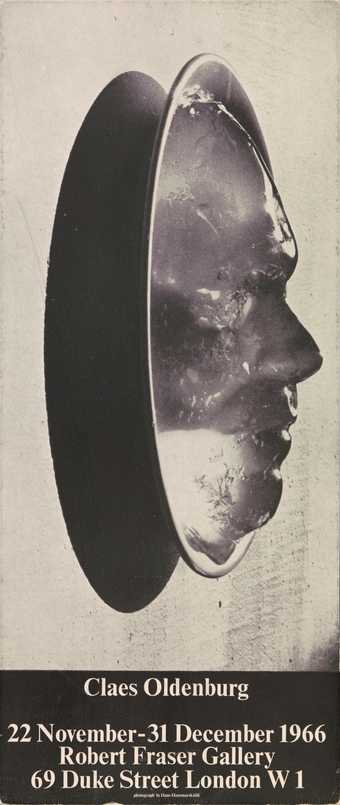

22 November – 31 December 1966

Claes Oldenburg

Robert Fraser Gallery, London

Cover of Claes Oldenburg, exhibition catalogue, Robert Fraser Gallery, London 1966

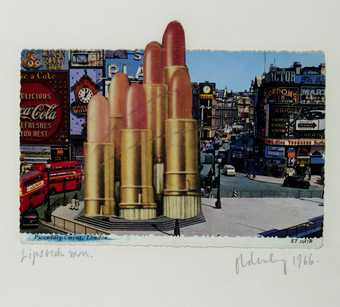

Claes Oldenburg

Lipsticks in Piccadilly Circus, London 1966

Tate T01694

© Claes Oldenburg

In advance of this exhibition, the first Oldenburg show in Britain, the artist visited London for the first time, where he collaborated with Editions Alecto on multiples inspired by his experience of the city. One of these was London Knees 1966, an editioned portfolio consisting of a pair of knees made of latex and lithographs which imagined them as colossal monuments on the London skyline. It responded to the recent inventions of the miniskirt and go-go boots, and Oldenburg later recalled that ‘London’s Oxford Street was a sea of knees’.40

Seven of the sketches for imaginary monuments were shown in the exhibition, and Oldenburg drew further proposals and pasted them onto postcards of the city. Lipsticks in Piccadilly Circus, London 1966, which Tate acquired in 1972, showed an array of overtly phallic lipsticks in place of the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus.

4 April 1967

Opening of the Lisson Gallery, London

Photograph of the facade of the Lisson Gallery, Bell Street, London, 1973

Photographer unknown

After initially showing mostly British artists, the Lisson Gallery went on to play an important role in making American minimalist and conceptual artists better known, giving many of them their first solo shows in Britain. These included: Sol LeWitt: Walldrawings, Drawings, Prints (14 June – 24 July 1971); Carl Andre (10 October – 27 November 1971); Dan Graham (25 February – 18 March 1972); Mel Bochner (6–29 April 1972); Robert Ryman (5 December 1972 – 2 January 1973); Robert Mangold (27 February – 24 March 1973); Dan Flavin (20 November – 22 December 1973); and Fred Sandback: Constructions and Drawings (13 October – 19 November 1977).

6 January – 4 February 1968

Installation view of the exhibition Roy Lichtenstein, Tate Gallery, London, 1968

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Roy Lichtenstein 1968

This exhibition was organised by the critic, curator and artist John Coplans for the Pasadena Art Museum, after which it toured to the Tate Gallery in London, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Kunsthalle Bern and the Kestnergesellschaft in Hanover.

During the Tate Gallery exhibition, a film Lichtenstein in London was made which recorded viewers’ diverse responses. The first show of pop art at the Tate Gallery, it attracted a range of new audiences. Sunday Times critic John Russell observed, ‘to see some of them marching through the entrance hall, looking neither to left nor to right, you would think that all older art was contaminated’.41 In the Annual Register the Courtauld lecturer and future Tate director Alan Bowness praised the exhibition’s ‘spectacular success’.42

8–28 March 1968

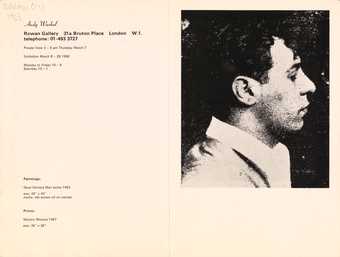

Andy Warhol

Rowan Gallery, London

Spread from Andy Warhol, exhibition catalogue, Rowan Galley, London 1968

© Warhol Estate

Warhol’s work was first shown in Britain as part of Popular Image USA in 1963, but surprisingly it took several more years for a British gallery to organise a solo show of his work.

The Rowan Gallery opened in Belgravia in 1960 and initially specialised in British abstract art. Andy Warhol was one of its first exhibitions after it moved to Bruton Place in London’s Mayfair, for which the list of works consisted of only two entries: ‘Paintings: Most Wanted Men series 1963’ and ‘Prints: Marilyn Monroe 1967’.

Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men paintings were originally executed as a mural for the 1964 New York World’s Fair but were deemed unsuitable and painted over, leading Warhol to make a new set of paintings of the images for exhibitions. The Times critic Guy Brett, who was disappointed by the London exhibition, judged that whereas Warhol’s original decision to exhibit the work at the World’s Fair was ‘a brilliant choice of context’, an exhibition ‘where works are merely sent over and hung’ failed to incorporate the collaborative and site-specific element which he believed characterised Warhol’s best work.43

11 April – 29 May 1968

The Obsessive Image 1960–1968

Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Cover of The Obsessive Image 1960–1968, exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1968

Paul Thek

The Tomb (interior view), Stable Gallery, New York 1967

© The Estate of George Paul Thek; courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Photo © John D. Schiff

The Obsessive Image was the first exhibition held by the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) after it moved from its original home on Dover Street to its present site on the Mall. A survey of images of the human figure in 1960s art, the exhibition featured a number of American artists. It included the sculpture of George Segal, seen for the first time in London, and the first European screening of Andy Warhol’s six-hour-film Sleep that ran non-stop throughout the show.

The show also included Paul Thek’s The Tomb, which the ICA’s press release described as ‘a tomb in which reposes a life-sized dead Hippie’.44 This famous work, now lost, was exhibited for only the second time at the ICA, following its inaugural showing at New York’s Stable Gallery the previous year. On the BBC discussion forum The Critics, writer Marghanita Laski described the show as ‘the best exhibition of contemporary art that I think I've seen’.45

1968

Rothko presents Black on Maroon 1958 to the Tate Gallery

Mark Rothko

Black on Maroon 1958

Tate T01031

© Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/ DACS

Maquette for the installation of Rothko’s Seagram murals at the Tate Gallery

Tate Archive Photographic Collection

© Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko / DACS 2019

Photo © Tate

Rothko’s relationship with the Tate Gallery deepened following its early purchase of his work in 1959. In 1965 he began discussing the possibility of making a gift to the gallery with its director Norman Reid, and eventually presented Black on Maroon in 1968, with Reid and Rothko settling on eight further paintings when Reid visited him in New York in late 1969.

The works were originally executed as part of a commission to paint a series of murals for the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building in New York, but Rothko withdrew from the project, feeling that the works would not be suited to the opulent restaurant setting. The group was hung together in a dedicated ‘Rothko room’ at the Tate Gallery, planned in consultation with the artist (Reid made Rothko a small model of the planned room to facilitate this), and has mostly been shown together ever since.46 In a letter to Reid dated 15 July 1968, when faced with short-lived delays in moving the project forward, Rothko wrote wistfully, ‘I still hold the room at the Tate as part of my dreams’.47

8 December 1968 – 26 January 1969

Willem de Kooning

Tate Gallery

Installation view of the exhibition Willem de Kooning, Tate Gallery, London, 1968–9

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Willem de Kooning 1968–69

Of the main protagonists of the New York School, Willem de Kooning was one of the last to have a solo show in Britain. (Barnett Newman, whose work was shown at the Tate Gallery in 1972, and Clyfford Still were the other exceptions.) Tate’s exhibition proved to be the most comprehensive show of de Kooning’s work to date. Like many others, it was organised by the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The exhibition’s curator, the critic and editor Thomas Hess, noted: ‘This is Willem de Kooning’s exhibition. He made an initial selection of pictures that he thought would best represent him. Whenever possible this was followed’.48

24 April – 1 June 1969

Installation view of the exhibition The Art of the Real: An Aspect of American Painting and Sculpture 1948–1968, Tate Gallery, London, 1969

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: The Art of the Real: An Aspect of American Painting and Sculpture 1948–1968 1969

This touring show, organised by E.C. Goossen for the Museum of Modern Art, was the first exhibition in Britain to foreground the minimalist sculpture of artists such as Carl Andre, Donald Judd and Tony Smith. While many commentators took issue with the show’s title, which they saw as misleading, most were grateful to have the opportunity to see these new works (and called for more sustained presentation of the artists). The critic Nigel Gosling saw it as proof that ‘in America today many fine artists are working in an idiom which makes most European art look fussy, illustrative, sentimental and frivolous’.49 Gosling also detected in the works ‘an almost ostentatiously masculine flavour, wary of prettiness, sentiment or little every day consolations’.

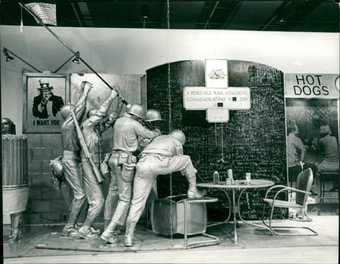

9 July – 3 September 1969

Installation view of Edwards Kienholz’s Portable War Memorial 1968 in the exhibition Pop Art, Hayward Gallery, London, 1969

In their catalogue introduction the exhibition organisers John Russell and Suzi Gablik emphasised that owing to space restrictions the exhibition consisted of ‘Anglo-American Pop only’, and confessed that it was also ‘weighted in favour of American Pop, of which the English public has had almost no first-hand experience’.50 Several leading pop artists had been exhibited in London in the preceding years but the Hayward show was the largest and most comprehensive pop art exhibition in Britain to date.

The critic and curator Guy Brett wrote that ‘two environmental works dominate the show: Edward Kienholz‘s “Portable War Memorial” and Claes Oldenburg’s “Bedroom”’.51 Oldenburg’s work was, in the words of the curator Bryan Robertson, ‘a reconstruction of a sort of Ann Sheridan-Lana Turner bachelor girl bedroom of the 1940s: bed and chest of drawers at a treacherous slant, replete with equally disturbing echoes in the form and finish of detail and materials’.52 Kienholz’s tableau had been constructed the previous year at the height of the Vietnam War. When first shown in San Francisco it was described by Rolling Stone writer Thomas Albright as a ‘mammoth sculptural assemblage ... an epic masterpiece, comparable in its way to “The Last Supper”’.53 Kienholz received further exposure in Britain in 1971 when the important travelling exhibition of his work, organised by Pontus Hulten for the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, was shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA).

The response to the Hayward Gallery exhibition showed that pop art retained its appeal among the young. The critic John Russell wrote to curator and critic Lawrence Alloway that pop was still controversial and only young people were visiting the show.54 Meanwhile Robertson, whose exhibitions of artists including Rauschenberg and Johns at the Whitechapel Gallery a few years earlier had been so important in bringing new American art to Britain, described the exhibition as an ‘ordeal’ and concluded in his review that pop art was ‘essentially for disenchanted millionaires … a bland art from which any possible sting has been removed’.55

28 August – 27 September 1969

Live in your Head: When Attitudes Become Form (Words-Concepts-Processes-Situations-Information)

Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Cover of Live in your Head: When Attitudes Become Form (Words-Concepts-Processes-Situations-Information), exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1969

This seminal exhibition of arte povera, minimalist and conceptual art was first curated by Harald Szeemann for the Kunsthalle Bern, from where it toured to Museum Hause Lange in Krefeld, Germany and then to the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. Here it was curated by the art historian and critic Charles Harrison.

The critic Guy Brett wrote in his Times review that the exhibition, consisting of ‘fragmentary and casual objects which scatter the floor or lean against the wall’, looked ‘different from any international mixed exhibition of new art I have seen before’.56 Many of the works were by American artists including Carl Andre, Richard Artschwager, Robert Barry, Mel Bochner, Michael Heizer, Douglas Huebler, Edward Kienholz, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Walter de Maria, Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman, Claes Oldenburg, Dennis Oppenheim, Robert Ryman, Fred Sandback, Richard Serra (listed, but Harrison later doubted his work was included), Robert Smithson, Keith Sonnier, Richard Tuttle and Lawrence Weiner.57 Some of the artists, including Smithson and Artschwager, travelled to London for the exhibition.58

1969

The Tate Gallery publishes Recent American Art by Ronald Alley

Cover of Ronald Alley, Recent American Art, London 1969

Ronald Alley, Keeper of the Modern Collection at the Tate Gallery, began his introduction to Recent American Art:

That it has been possible to draw all but four of the illustrations to this book from the Tate Gallery’s own collection is indicative of the enormous international interest in recent American art. British artists were among the first outside the United States to recognise the importance of the new American painting and to be influenced by it; and since about 1950 New York has tended to supersede Paris as the principal creative centre for painting.59

He went on to attribute the rapid change in status of American art to the formation of several superb private and public US collections of modern art, and to the influx of leading European artists as visitors and as refugees, during the war, before discussing the stylistic developments in post-war American art.

In his foreword to the volume Director Sir Norman Reid pointed out with some pride that from a ‘modest beginning in 1959 with the purchase of paintings by Rothko, Guston and Brooks the post-war American collection has grown until it now numbers more than fifty works’.60 He also went on candidly to list the artists that the collection still lacked: Gorky, Still, Reinhardt, Gottlieb, Motherwell, Rauschenberg and Oldenburg.