In January 1956 the American artist Ben Shahn arrived in London with his wife, the painter, printmaker and photojournalist Bernarda Bryson. It was Shahn’s second, and last, visit to the city (the first was when he passed through as a boy of seven, fleeing the anti-Jewish pogroms in this native Lithuania for a new life in New York).1 The trip was occasioned by the inclusion of five of his works in the exhibition Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the first major show at the Tate Gallery devoted exclusively to contemporary American painting, sculpture and printmaking. It was during his two-week stay in London that Shahn delivered a lecture to a packed house at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) called ‘Realism Reconsidered’, the focus of this essay.

Shahn might have used this opportunity to commend the curatorial aims of the exhibition in which he was currently featured; or to publicly extend his gratitude to its organiser, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which had also arranged his acclaimed retrospective at the Venice Biennale two years earlier. In his lecture, however, he instead took aim at the canonisation of abstract tendencies in the United States, and criticised the control of museum curators and art critics over the reception of American art. As will be seen, his analysis exemplified the spirited debate among post-war American artists, who advocated competing narratives about modern art and its aims, values and significance.

Scholarship of early Cold War cultural diplomacy has tended to emphasise America’s pursuit of global hegemony through the exhibition of abstract expressionism.2 Yet Shahn’s visit to London highlights the role played by diverse practices in strengthening the US’s international standing in competition with the Soviet Union, and reveals how pluralism in American art was, just as much as abstraction, associated with a prevalent rhetoric of freedom and democracy. It is also perhaps surprising to learn that the artist’s transatlantic trip was partly funded by the United States Information Agency (USIA), the US government’s overseas propaganda organisation, given that Shahn’s left-wing political activism was the subject of an FBI investigation in the mid-1950s when the McCarthyite witch-hunts reverberated through American cultural life. Shahn’s visit also shows the US government’s sensitivity to current political circumstances in other countries when considering what view of America to present in its overseas propaganda activities. Challenging the binary narratives that dominate discussion of the politics of American art at mid-century even today, this essay will look at the significance of Shahn’s visit to London at a moment of profound shift in the Cold War, and the impact of his reception on both sides of the Atlantic.

A warm reception

Although Shahn’s time in London in 1956 marked his first visit to Britain as an established artist, he had already made two extended trips to Europe in the mid- and late 1920s. He had travelled to Italy, Spain, Austria, Holland and France, remaining in Paris for a prolonged period to study at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Later Shahn recalled how his formative artistic experiences were European, and that American influences affected the development of his work only after he had travelled extensively in the US as a photographer for the Farm Security Administration in the late 1930s during the New Deal – the programme of initiatives instituted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt aimed at rejuvenating the American economy during the Great Depression.3 Shahn professed to having been influenced by fauvism and expressionism, as well as the social commentary found in the works of British artist William Hogarth (1697–1764) and French artist Honoré Daumier (1808–1879); Bryson also recalled her husband’s lasting appreciation for the ‘implied surrealism’ of contemporary artists such as Balthus.4

Fig.1

Ben Shahn

Handball 1939

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

Fig.2

Ben Shahn

Liberation 1945

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

Shahn’s enthusiasm for Europe was warmly returned by its audiences, and his visit to London happened when his reputation was at its pinnacle in Britain. Three of his paintings had been shown at the Tate Gallery in the 1946 exhibition American Painting from the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day, the first major British display dedicated to the art of the United States.5 The show had included one painting from Shahn’s Sacco and Vanzetti series, which in total consists of twenty-three small paintings and two large panels honouring the Italian-born anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. Sacco and Vanzetti’s presumed innocence of the crime of double homicide, for which they were executed, had been a cause célèbre among left-wing artists and intellectuals in the 1920s. The Tate exhibition had also included Handball 1939 (fig.1), a muted and ambiguous depiction of blue-collar workers, and Liberation 1945 (fig.2), which recalled the devastation wrought on Europe by the Second World War. In the following year a small display of sixteen paintings by Shahn was shown at the F.H. Mayor Gallery in London before travelling to galleries in Brighton, Cambridge and Bristol under the auspices of the Arts Council of Great Britain. However, Shahn’s work remained little-known to British viewers until later in 1947, when James Thrall Soby’s monograph of the artist was published in both New York and London to coincide with his retrospective at MoMA.6 The volume became one of the best sellers in the Penguin Modern Painters series, and was lauded by the Sunday Times for the high quality of its sixteen colour plates, which were said to have had a ‘remarkably strong’ influence on British art students.7 By 1954 Guardian art critic Stephen Bone noted frequent references to Shahn’s pre-1947 style in the works on display in graduate art shows across the United Kingdom:

Constantly in students’ sketch-clubs or in such exhibitions as ‘Young Contemporaries,’ or ‘Paintings for Schools’ one sees the neat, expressive, coloured silhouettes that often look as if cut out with scissors; the accurate but very selective painting of detail; the slight deliberate awkwardness in the composition; the choice of subjects from the garage, the poor street, the cheap shop, the railway station. Sometimes one finds also something of Ben Shahn’s great compositional inventiveness and his dry wit.8

That summer, the ‘Shahn School’ that was burgeoning in Britain’s art academies was bolstered by the artist’s inclusion in the twenty-seventh Venice Biennale.9 With thirty paintings and six drawings, Shahn had the highest number of works of all the artists in the US pavilion, although the larger scale of the twenty-six paintings and single drawing by his compatriot, Willem de Kooning, shifted the balance visually. At the time, press reports claimed that Shahn’s paintings had ‘done more for the prestige of the United States than any other exhibition of American art sent to Europe’.10 According to the Sunday Times, the event confirmed Shahn’s reputation as ‘the first American to have had any considerable impact upon European painting’, as well as ‘one of the world’s few great artists’.11

Many of Shahn’s young admirers were said to have attended his talk at the ICA on 2 February 1956. Perhaps this explains his decision to use this platform to express his frustration at what he saw as the restrictions imposed on early-stage artists, who were increasingly driven towards abstraction:

To be taught it is necessary that art be highly departmentalized. Thus is it thrust into all sorts of classes and categories: of meaning, of era, of place, of good and bad, of aesthetic persuasion, and often of the finer points of scholarship. Such categories, at first devised, no doubt, merely to provide some sort of geography by which the student or art lover may find his way about, tend to become fixed; to be regarded as fact rather than theory.12

Later in the talk, Shahn returned to the increasing inability of art schools to support experimentation and diversification in the work of students. Commenting on professional scholarship, he claimed that for the most part it ‘likes to arrange its world as neatly as possible so that it will operate satisfactorily, and not require any painful readjustments in established theory; that this year’s curriculum may be substantially the same as that of last year, and the even flow of intellectual life remain undisturbed’.13

Shahn censured Western art historians, curators and critics for forcing artists to produce work that conformed to one of a small number of easily identifiable categories, thereby preventing them from seeking their own creative path. To illustrate this strict departmentalisation, Shahn presented a detailed account of a book he did not identify by name but which was, in fact, the catalogue to MoMA’s 1951 exhibition Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, authored by its Director of Painting and Sculpture, Andrew Ritchie. Here the author identified two ‘waves’ of abstraction: the first dating from the 1913 Armory Show to c.1925, in which the influence of cubism and futurism was seen in the work of such artists as Max Weber, Joseph Stella, Lyonel Feininger, Marsden Hartley and Man Ray; and the second ‘wave’ dating from the onset of the Great Depression in late 1929 and continuing to the present day. Ritchie then divided the abstract art of this second period into five categories, each of which he illustrated with full-page artworks: ‘Pure Geometric’ (including Josef Albers, Sue Fuller and Theodore Roszak); ‘Architectural and Mechanical Geometric’ (the precisionism of Niles Spencer, Edmund Lewandowski and Ralston Crawford); ‘Naturalistic Geometric’ (Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, Norman Lewis and John Marin); ‘Expressionist Geometric’ (paintings by Stuart Davis, Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell, and sculptures by Alexander Calder and David Smith); and ‘Expressionist Biomorphic’ (William Baziotes, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, Isamu Noguchi, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko). Reviewing Ritchie’s list, Shahn observed acerbically that this level of categorisation was ‘practically eliminating the need to look at the paintings at all’.14

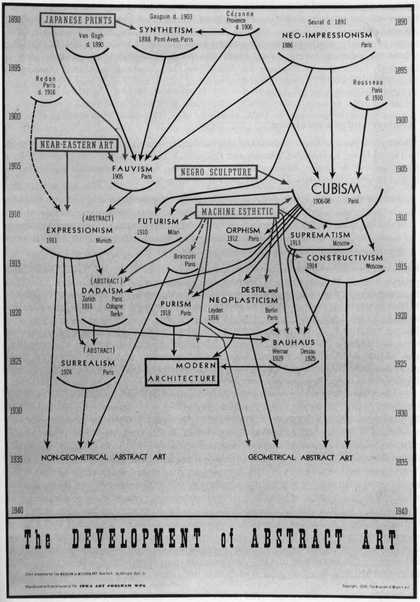

Fig.3

Alfred H. Barr Jr

‘The Development of Abstract Art’, in Cubism and Abstract Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1936

Fig.4

Ben Shahn

Willis Avenue Bridge 1940

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

Fig.5

Ben Shahn

Pacific Landscape 1945

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

The detailed classification of art by MoMA in the 1950s had its origins two decades earlier in the formulations of the museum’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr Jr. For the 1936 exhibition and publication Cubism and Abstract Art, Barr produced his now famous flowchart titled ‘The Development of Abstract Art’ (fig.3). Through this, he instilled in a generation of American art critics, artists and historians the idea that contemporary geometric and non-geometric abstraction was the outcome of fifty years of European avant-garde experimentation. Tate‘s 1956 exhibition Modern Art in the United States, organised by MoMA’s International Program and composed almost entirely of works drawn from its own collection, similarly demonstrated the American museum’s efforts to categorise recent developments in American art. The paintings were divided into five sections: ‘Older Generation of Moderns’; ‘Realist Tradition: Fact, Satire, Sentiment’; ‘Romantic Painting’; ‘Contemporary Abstract Art’; and ‘Modern “Primitives”’. Shahn was assigned to ‘Realist Tradition: Fact, Satire, Sentiment’, alongside such artists as Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth. Handball (fig.1) was shown again, alongside another painting from the Sacco and Vanzetti series. In addition, Willis Avenue Bridge 1940 (fig.4) was shown as a typical example of Shahn’s New Deal-era social realism, depicting two smartly dressed African American women sitting on a bench, one of whom is holding crutches. However, Pacific Landscape 1945 (fig.5) represented a departure from Shahn’s earlier style and was more in keeping with his work of the 1950s. On an almost abstracted landscape of pebbles and sea, Shahn painted a prostrate figure, partly based on a found photograph of a dead American soldier on a beach in northern France.15

The painting was reproduced in black and white in the exhibition catalogue. Significantly, all of Shahn’s paintings in the exhibition dated from before the end of the Second World War, and so did not challenge the conclusion in the catalogue’s introductory essay by former MoMA acting director Holger Cahill that over the course of the 1940s abstraction ‘had become the dominant trend in American painting’.16

Cahill mirrored Barr and Ritchie in expounding a rigid stratification of art trends and detailing multiple categories of abstraction. Despite his earlier directorship of the New Deal-era Federal Art Project, Cahill also downplayed the importance of social realist art in the US, save for his discussion of the work of Shahn and Jack Levine.

In his talk at the ICA, Shahn expressed unease at the increasing marginalisation of realism as an artistic style, with concepts of ‘beauty’ and ‘truth-to-nature’ similarly seen to be outmoded. Instead, ‘the new aesthetics of the isms’ had gained popularity, supported by an unprecedented body of scholarship and art criticism. At the same time, a conservative backlash against modernism meant that representational modern art was being squeezed in the middle, with ‘academic art on the one hand, and Non-objectivism or abstraction on the other constituting those opposite extremes of subject-matter and functionalism from both of which content has been excluded’.17

Shahn lamented that, in particular, social realism was despised, with the term increasingly used by critics ‘to write off the intransigent movements in art, and it is not infrequently used to disparage all art which shuns the Abstract-Non-Objective aesthetic’. The artist also noted how diminished appreciation for social realism in the United States had coincided with the codification of socialist realism as the official artistic doctrine of the Soviet Union. However, while acknowledging a tendency towards ‘academic rigidity’ in the production of much realist art on both sides of the Cold War divide, Shahn argued that a similar blinkeredness affected those ‘dictating the modern aesthetic, proscribing from art any deviation from the present convention’. Shahn mischievously identified this tendency through the introduction of his own ism: ‘If Social Realism seeks to impress upon art a rigid aesthetic of subject matter and point of view, there also exists another opposite camp which seeks with equal rigidity to exile from art all meaning – to keep it free from any content whatsoever. This is the camp of Pedantism.’18

A Tepid Relationship

Fig.6

Installation view of Ben Shahn’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, showing works from the Sacco and Vanzetti series 1948

Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Fig.7

Ben Shahn

The Red Stairway 1944

Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis

© Estate of Ben Shahn/Licensed by ARS, New York, NY

Shahn’s apparent animosity towards MoMA in his ICA talk evidenced a fluctuating relationship between the artist and the museum that was never resolved. In 1949, during one of his series of infamous congressional diatribes against American modern art, Michigan Representative George Dondero disparaged Shahn as ‘one of the pets of the Museum of Modern Art’, while accusing the institution of being at the centre of a communist conspiracy.19 Indeed, the New York museum proved to be a steadfast supporter of the artist throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Shahn’s works were first exhibited at MoMA in 1932, three years after its foundation, and he was once again featured in its fifth anniversary exhibition in 1934. Following the inclusion of eleven of his paintings in the 1943 exhibition American Realists and Magic Realists, Shahn was granted a retrospective that opened on 30 September 1947. Although dominated by fifty-five paintings, the exhibition also included sketches for murals that Shahn produced during his ten years contributing to the New Deal art programmes, as well as drawings, book illustrations, a small group of photographs, and posters he designed for the US Office of War Information and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a federation of trade unions. Special attention was paid to a selection of gouaches from Shahn’s Sacco and Vanzetti series (fig.6). Other works focused on the persecution of the San Francisco labour leader Tom Mooney, and the show also included preparatory paintings from Shahn’s satirical series Prohibition, produced under the auspices of the Public Works of Art Project for an unrealised mural. The following year, the success of Shahn’s retrospective led him to be appraised as America’s fifth best painter in an anonymous poll of museum directors, curators and art critics that was carried out by Look, a popular biweekly general interest magazine. Shahn appeared below John Marin, Max Weber, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Stuart Davis in a list that Look noted had eschewed both ‘surrealists and very abstract work’ as well as ‘old-fashioned, ultra-realistic painting still favored by large sections of the public’, to instead celebrate ‘a high quality, middle-of-the-road selection that will be questioned both by arch conservatives and by the most advanced abstractionists’.20 The feature was illustrated by Shahn’s disturbing and surrealistic painting The Red Stairway 1944 (fig.7), which was said by Look to symbolise the ‘helplessness of life in Europe’s rubble’.

Despite these tributes, Bryson recalled that, by the late 1940s, Shahn had become increasingly vocal against what he saw as an attempt ‘to turn artists into an army of sycophants’, whom he envisaged as ‘barricaded on one side or the other of some unspecified no-man’s land, never venturing across the forbidden terrain’.21 This position brought him into conflict with advocates for American abstract art. In a particularly acrimonious episode, Shahn provoked the ire of painter Robert Motherwell, the de facto spokesman for the disparate circle of artists designated ‘abstract expressionists’. In a lecture to the College Art Association in 1950, which constituted the first attempt to publicly define the New York School, Motherwell called Shahn ‘the leading Communist modern artist in America’. Retaliating against Shahn’s accusation in 1949 that Motherwell created decorative art without content, Motherwell went on to describe Shahn’s paintings as containing ‘no feeling for real humanity and its capacity for self-realization. Instead his art seems to me to be cold, empty, mechanical, and alienated from the world.’22

In the aftermath of Motherwell’s attack, Shahn’s relationship with MoMA soured. In 1951 Shahn wrote an open letter to director René d’Harnoncourt criticising the museum’s disproportionate display of non-representational tendencies. Portraying MoMA as the major exponent of ‘the fast-spreading doctrine that non-objectivism has achieved some sort of esthetic finality that precludes all other forms of expression’, the letter called on the museum to recognise a ‘humanistic reawakening’ in the US.23 But Shahn chose to hide his authorship of the letter, allowing it to be attributed to fellow left-leaning painter Raphael Soyer and only undersigned by Shahn, along with twenty-one other artists.24 Shahn joined Soyer, Jacob Lawrence and Jacob Hirsch, however, in attending a meeting with MoMA’s directors in which the artists demanded an opportunity to present their work in the museum in an exhibition that would challenge the ascendancy of abstract expressionism. MoMA declined the proposition and, in private, Alfred Barr railed against the group as ‘party-liners (hence the emphasis on reality and humanism)’ and naïve fellow travellers ‘unaware of the political and ideological motivations of many of the others’.25

Fig.8

Front page of Reality: A Journal of Artists’ Opinions, no.1, Spring 1953

Moses Soyer Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Fig.9

Ben Shahn

Age of Anxiety 1953

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

Fig.10

Ben Shahn

Helix and Crystal 1957

San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

The meeting proved the catalyst for the establishment of the short-lived publication Reality: A Journal of Artists’ Opinions, of which three issues were published in 1953 (fig.8). Claiming to uphold the value of humanism within art, the magazine also provided a forum for opposition to the ‘esoteric cult’ over which MoMA was repeatedly accused of presiding.26 The first issue included an excerpt from ‘Paragraphs on Art’, a free pamphlet written by Shahn and published in 1952. Using similar language to that which would feature in his 1956 ICA lecture, Shahn defined the ‘search for truth’ as the most important quality in art and linked the prominence given to ‘mechanics’ in non-objective painting to the present ‘era of almost total mechanization and H-bombs’.27 In his talks and works of the period, Shahn often conflated his concerns about the dominance of abstraction in the American art scene and the threat posed by the nuclear arms race. At Smith College in 1949, the same year that the USSR exploded its first atomic bomb, he lamented ‘the great and tragic characteristics of the atomic age’, noting that ‘human values – morality, if you will, have not kept pace with scientific achievements’.28 Meanwhile, allegorical references in works such as Age of Anxiety 1953 (fig.9) and Helix and Crystal 1957 (fig.10) reaffirmed Shahn’s unease about nuclear armament.

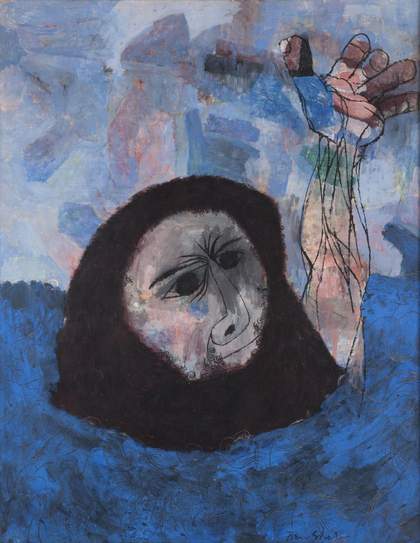

Fig.11

Ben Shahn

Caliban 1953

Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

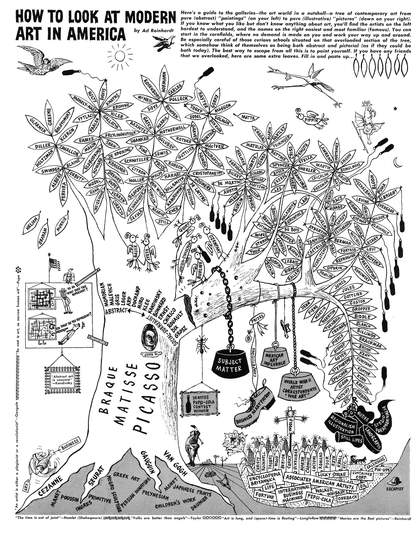

Fig.12

Ad Reinhardt, ‘How to Look at Modern Art in America’, PM, 2 June 1946, p.13

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Despite Shahn’s contributions to Reality, Bryson would later recall that he had an ‘ambivalent’ position towards non-objective art, as he admired the work of a number of abstract artists including Franz Kline, Pierre Soulages and Henri-Georges Adam.29 Indeed, by the mid-1950s Shahn was himself experimenting with abstract and semi-abstract imagery in prints such as Caliban 1953 (fig.11). However, Bryson remembers that Shahn resented the way that abstraction had come to monopolise artistic debate, and he was ‘in violent disagreement with its aesthetic view, which he believed dismissed all other forms of painting as spurious and as non-art’.30 According to his wife, Shahn was particularly uneasy with what he saw as the ‘artificially stimulated’ schism between abstract and figurative painting, fostered, he felt, by art critics and galleries rather than artists.31 Bryson’s recollections mirror Shahn’s testimony at the ICA. There, the artist admitted that ‘many visually exciting, even intellectually exciting works, have emerged from the great volume of Non-objective art,’ although he concluded that ‘today it has reached what might generously be called a plateau. Despite the best efforts of its artistic horticulturalists, the fruit hangs limp upon the branch.’32 Shahn’s botanical imagery is surely a veiled yet characteristically sarcastic allusion to How to Look at Modern Art in America, a 1946 illustration by abstract painter Ad Reinhardt (fig.12). In this antagonistic yet entertaining allegorical sketch, Reinhardt equates the contemporary art scene to a tree, its roots and trunk emblazoned with the names of European avant-garde artists of the early twentieth century. Each leaf then represents a modern artist working in the United States. While the leaves of Reinhardt’s own circle of abstract artists grow tall and strong directly above the tree trunk, the names of Shahn and other social realist and surrealist artists are relegated to leaves on a distant branch that appears about to snap under the weight of ‘subject matter’. In the introductory text, Reinhardt cautions readers to ‘be especially careful of those curious schools situated on that overloaded section of the tree, which somehow think of themselves as being both abstract and pictorial (as if they could be both today)’. Speaking at the ICA, Shahn rebuked this kind of excessive rhetoric and the theoretical pretensions employed by New York critics and curators in particular to claim:

As the new aesthetics of the isms gained popularity through the most prolific and passionate body of exegesis that art has ever known, the once-unassailable catch-words of the Academy fell low, and were ostracized from the society of the polite and the well-informed … Not only does Non-objectivism invite colourful rhetoric, but it also provides interesting material for scholarly speculation. I have been assured by one avante-garde [sic] critic that the austere horizontal-vertical discipline of Mondrian’s painting might be attributed to the celibate’s aversion to the roundness of a woman’s breasts … A very serious art historian has explained to me that the real significance of such work as that of Jackson Pollack [sic] lies in a space-time continium [sic], of which the work is a manifestation. ‘Any effort of will on the part of the artist,’ my historian explained, ‘any exercise of thinking of intention would interfere with the free flow of cosmic forces.’33

Shahn denounced what he saw as the unbridled authority of art critics, which he felt forced some artists to create according to the whims of fashion: ‘the critic is almost the only link between artist and public (a lamentable situation, in itself) and his power over the artist is heliotropic; whatever his aesthetic position, the artist turns that way.’34 Shahn also repeatedly condemned the suggestion by critics and theorists that ‘it is not within the scope or function of the artist to understand the meaning of his own work’, reiterating that

the formulation of an aesthetic is peculiarly and exclusively the task of the artist – and that is, the artist in any field. Only he can possibly know what sort of plastic means will realize his own peculiar kind of enlightenment. There are the implied truths, the deeper-than-surface meaning in every possible facet of reality whether grave or trivial, and only the man behind the eye can determine which way the eye shall see.35

A cold warrior

In a robust defence of MoMA’s reputation, after scepticism about its Cold War record and allegations of CIA funding had surfaced in the 1970s,36 the critic Michael Kimmelman reasserted the museum’s support for diverse practices during the 1950s. He framed the alleged links between the museum’s support for abstract expressionism and Cold War ideology in the context of contemporaneous anti-war protests and the civil rights movement.37 Reviewing why MoMA chose Shahn to represent the US at the Venice Biennale in 1954, art historian Frances Pohl argued that the left-wing artist was promoted as much for his political beliefs as for his art.38 Here it is also important to consider the extent to which MoMA’s interest in Shahn was related to his politics. After all, his political statements and artistic style enabled him to be employed as a propagandist for Cold War liberalism through representing an acceptable level of deviation from both mainstream anti-communism and the American avant-garde. The promotion of Shahn was in line with diplomatic efforts to associate the moral implications of pluralism with the twin ideologies of freedom and democracy, an aspect of US artistic rhetoric during the early Cold War that is often neglected in scholarship.

Fig.13

Ben Shahn

Hunger 1946

Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, Auburn University, Auburn

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

As a first generation immigrant from a country that had been subsumed into the Soviet Union, Shahn was an obvious subject for suspicion as anti-communist paranoia gripped the United States in the first decade of the Cold War. Although Shahn defined himself as a social democrat, the artist had a long history of contributing to radical left-wing causes and many in his social circle, including his wife Bernarda Bryson, had been one-time members of the Communist Party. As Senator Joseph McCarthy used accusations of communism to attack public figures, educators and government officials who were seen as a challenge to conservative values, the dangers posed by ‘McCarthyism’ were first revealed to Shahn in the furore surrounding the 1946 exhibition Advancing American Art. This two-part overseas propaganda show was organised by the US State Department, which intended for it to tour Europe and Latin America for the next five years. Yet soon after it was first shown, conservative groups and politicians probed the political records of featured artists and claimed the exhibition had been infiltrated by communists. Look magazine reproduced Hunger 1946 (fig.13), one of three works by Shahn in the exhibition, to illustrate a hostile editorial provocatively titled ‘Your Money Bought These Paintings’.39 The work had also been reproduced that year on a CIO poster encouraging voter registration, with the caption ‘We Want Peace’. The conservative backlash against this and other works of social commentary would bring about the early closure of the exhibition in 1947.40

Fig.14

Ben Shahn in his studio, Roosevelt, New Jersey, 1940

Ben Shahn Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Two years later, George Dondero decried Shahn’s membership of left-wing artistic organisations, said to be communist front groups. As part of his McCarthyite campaign against a supposed communist conspiracy undermining American art, Dondero condemned Shahn in particular for his illustrative contributions to New Masses, a cultural magazine associated with the US Communist Party. The politician also viewed with suspicion Shahn’s apprenticeship to the famous Mexican muralist Diego Rivera in the early 1930s. Shahn had assisted Rivera in producing frescoes in the Rockefeller Center which were subsequently covered over and destroyed because they included a picture of Lenin, leader of the 1917 Russian Revolution.41 Dondero later accused Shahn of having ‘revolutionary aims’, calling a broad grouping of socially engaged artists ‘soldiers of the revolution – in smocks’.42 The FBI had started a file on Shahn in 1940, noting that his ‘work in the modernistic art field has shown a tendency to play up the lower class’.43 In the aftermath of Dondero’s speeches, Shahn’s home and studio in Roosevelt, New Jersey (fig.14) were put under surveillance, and in 1952 the FBI went so far as to explore the possibility of deporting the artist, upon finding no record of his application for American citizenship following his childhood emigration.44

The politics of the Cold War became more nuanced in the mid-1950s, as the USSR re-engaged with the international community after the death of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, and invested in propaganda to improve its reputation abroad. Western Europeans were encouraged to view the country with greater sympathy during this brief period of cultural liberalisation known as ‘Khrushchev’s Thaw’, named after Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s replacement as leader. Following the first post-war meeting between Khrushchev, US President Dwight Eisenhower, UK Prime Minister Anthony Eden and French Prime Minister Edgar Faure in the summer of 1955, the Soviet authorities announced their intention to revive international cultural exchange.45 In the following year, the USSR pavilion reopened at the Venice Biennale, marking the country’s first participation in a western cultural exhibition since the Second World War. These developments unnerved many in the United States, who saw them as a ploy to undermine the success of the US’s tactic of using cultural engagement to improve its relationship with other countries. On the occasion of MoMA’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1954, President Eisenhower acclaimed the New York institution as ‘a great museum of art in America’ that was leading the fight for ‘freedom of the arts’ in the face of the communist threat. With a board that included Nelson Rockefeller, John Hay Whitney, and other extremely wealthy patrons who held positions on government-sponsored committees, MoMA was already well placed to contribute to America’s Cold War strategy. This allowed the US government to circumvent the censure of McCarthyite factions by outsourcing cultural diplomacy.46

The International Program, launched in 1952 with financial backing from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, consolidated the museum’s position at the forefront of the international promotion of American modern art. With MoMA’s purchase of the US pavilion in Venice in 1953, making it the only non-governmental organisation to own a national pavilion in Venice, the museum confirmed its central role in disseminating American art as a Cold War ‘weapon’.47 Due to his political record, in 1953 the State Department vetoed Shahn’s nomination by a committee of leading US museum officials as the American painter most worthy of being represented in an important foreign exhibition.48 In the new political climate, however, both MoMA and the newly formed USIA, which took over responsibility for many cultural initiatives from the State Department, recognised Shahn’s potential in advancing the international reputation of American art.

Shahn’s work was much in evidence in the first exhibitions organised by MoMA’s International Program. Andrew Ritchie chose Shahn to appear in Twelve Modern American Painters and Sculptors, a touring exhibition that travelled to Paris, Zurich, Dusseldorf, Stockholm, Helsinki and Oslo between April 1953 and March 1954. Shahn was also one of fifteen painters and graphic artists to feature in the official US exhibition at the second São Paulo Biennial, which opened in December 1953. In Brazil he was awarded the Purchase Prize for Drawings, before also receiving the Purchase Prize in Venice in 1954, vindicating the museum’s faith in the artist. Following the MoMA directors’ selection of Shahn to be included in the Modern Art in the United States exhibition, Shahn’s visit to speak in London was sponsored by the International Council of MoMA and USIA. During his visit, the United States Information Service (the USIA’s international wing) arranged a dinner in Shahn’s honour with ICA director Roland Penrose and Tate deputy director Norman Reid, and subsequently arranged the publication of his talk in an issue of Perspecta in 1957.49

The investment made by MoMA and the US government in promoting Shahn in Europe, despite his record of radicalism, calls into question the polarising narratives of American art of this period. In his 1947 monograph of Shahn, James Thrall Soby – then chair of MoMA’s department of painting and sculpture – positioned Shahn as a cypher of political pluralism: ‘Shahn, who belongs to the Left, is appreciated by both Left and Right; his work has been published in conservative magazines as often as in liberal; he has fulfilled commissions for labor unions and for industrial corporations; his paintings are bought on completion by collectors of every political hue.’50 Dondero’s speeches of 1949 were said to have forced modern artists and their proponents into what Aline Louchheim, assistant art editor of the New York Times, described as a ‘common, courageous front’.51 The following March, the directorate of MoMA, the Boston ICA and the Whitney Museum of American Art released a joint statement in defence of modern art. Resolutely political, the statement equated artistic plurality and ‘freedom of expression’ with democratic society, and conflated the anti-communist campaign against modern art with creative repression in Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany.52 Alfred Barr also recognised the value of artistic pluralism as a Cold War policy, recommending in 1952 that the process of selecting artworks for overseas exhibitions organised by MoMA’s International Program should consider not solely their quality but also an ability to convincingly demonstrate the country’s ‘tolerance for self-criticism and diversity of social attitudes’.53

In both Soby’s book and MoMA’s press release for Shahn’s 1947 retrospective, the artist was commended as a ‘propagandist’.54 This language supports the claim that it was Shahn’s politics as much as his art that made him a favoured choice for MoMA’s exhibitions. However, despite the museum’s professed ability to tolerate diverse political viewpoints, it did not support many other American artists on the left, who were increasingly marginalised during the 1950s. It would seem therefore that Shahn’s vocal criticism of art from the USSR was also key in making the artist an appealing cultural ambassador for the US.55 Evidence for this supposition is found in a 1956 letter from Alfred Barr to the editors of the College Art Journal, in which the curator wrote in defence of Shahn, as an example of a modern artist who had faced unfair discrimination because of his supposed ‘subversive’ record. Barr instead reproached him merely as one of many ‘gullible liberals’ who had continued to believe that peaceful relations were possible with the Soviet Union, soon after the countries’ Grand Alliance. As evidence of Shahn’s innocence, Barr stressed that the artist had since spoken ‘with extreme bitterness of the communist infiltration and corruption of liberal movements and with equal vigor against Soviet art policies’.56 Barr quoted from a lecture Shahn gave in 1952 at the University of Buffalo, where he had spoken alongside Andrew C. Ritchie at a symposium on ‘The Future of the Creative Arts’ – perhaps an occasion that fuelled Shahn’s disregard for the curator’s categorisation of modern art which would find expression in his talk in London. In Buffalo, Shahn espoused his politically acceptable opinion of art in the USSR by equating it with art under the Nazi regime:

Communist doctrine, again, holds art to be a weapon, and has harnessed it to the uses of the State. Neither the formulae of commissars, nor inducements of honor, nor pretentious awards have yet succeeded in breathing life into Soviet art. Its deadly procession of over-drawn generals and over-idealized proletarians bears sharp testimony to the fact that there is no conviction in the artists’ hearts, and that the search for truth has been stalled.57

Soon after Shahn’s lecture, Barr took a similarly anti-Soviet position while defending modern art in the New York Times, suggesting that Shahn’s words had inspired the curator’s attention-grabbing op-ed. By again conflating socialist realism with art produced to glorify the Nazi regime, Barr persuasively reinforced the links between American art, democracy and political freedom.58 Shahn would return to the theme in his talk in London, once again dismissing Soviet socialist realism as ‘singularly unproductive’ and arguing that ‘until the Soviet artist is free to seek truth and create reality wherever he happens to see it … his art will present the same degree of emotional grayness and unconvinced socialism as it does today’.59

MoMA’s faith in Shahn proved to be well placed. Despite presenting the US art establishment in less than glowing terms in his lecture at the ICA, Shahn’s candid view of art across the Atlantic resonated in Britain more than the triumphant tales of America’s supremacy in the visual arts. In turn, this persuaded commentators to see American artistic culture as diverse and liberal, achieving the diplomatic aims of MoMA and the USIA. In 1953 Shahn had been forced to defend himself against accusations of communism in an interview with the FBI, arguing that ‘he was interested in peace and would offer his assistance to any group that he thought was working for a good cause’.60 The artist would find that this defence was more readily accepted in Britain, where left-wing views continued to gain more traction than on the other side of the Atlantic. In an article in the Sunday Times, Shahn was warmly characterised as a ‘liberal radical’ and ‘one of the most gentle and pugnacious artists alive, a quiet-speaking man of peace invariably involved in battle’.61 It was perhaps the favourable conditions in London that empowered him to criticise openly the effects of anti-communism on American art. The Sunday Times expressed equal admiration for Shahn’s controversial stance against ‘the essential sterility of abstract and non-objective painting’, and appeared to revel in his disrepute among avant-garde critics.

The response in Britain to Shahn’s work mirrored his success at the Venice Biennale two years previously. Frances Pohl has argued that Shahn’s public political statements ideally suited the US government’s attempts to shore up liberal democracy in Italy at a time when communism and neo-fascism were on the rise. In his public endorsement of the policies of Truman and Eisenhower, his commitment to democracy as ‘the most appealing idea that the world has yet known’,62 and his fierce denunciation of both communism and McCarthyism, Shahn represented, Pohl has argued, ‘humanism, free speech, anti-communism, and anti-fascism, aspects of America’s liberal democratic ideology that, in 1954, contributed to the improvement of the American image in Europe, and particularly in Italy, much more effectively than the aggressiveness of abstract expressionism’.63 In his talk at the ICA, Shahn’s self-characterisation as an outsider taking a brave stand against the mighty US art establishment likewise cast him as an ally to British and European artists, whose work was being eclipsed in international exhibitions by the rapid ascendancy of the New York School. Thus, in Britain as well as in Italy, Ben Shahn proved to be an appealing face of modern American art and an effective ambassador for its representation as an art worthy of the leader of the ‘free world’.

Epilogue

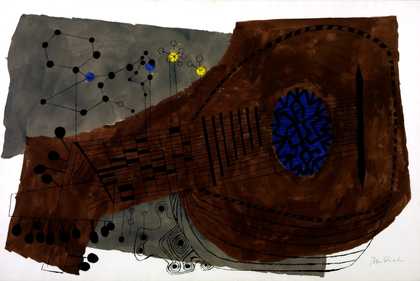

Fig.15

Ben Shahn

Lute and Molecules 1958

Tate T00314

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

Although Ben Shahn would not return to London, his work was exhibited in the city twice more during the artist’s lifetime, in 1959 and 1964 at the Leicester Galleries. It was at the first of these exhibitions, dedicated to Shahn’s graphic work, that Tate acquired the print Lute and Molecules 1958 (fig.15), ensuring his work found a permanent home in Britain. Meanwhile, in the United States, Shahn continued to enjoy a more successful career in the early Cold War than most of his left-leaning artist friends. In 1956 alone, he was awarded a gold medal at the annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and had a retrospective at the Fogg Museum at Harvard University, where he was also given an honorary professorship.

Fig.16

Ben Shahn

Parable 1958

Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica, New York

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

Despite the ongoing support of MoMA and the USIA, however, Shahn continued to be targeted by the anti-communist crusade. In 1959 his painting Parable 1958 (fig.16) was one of forty-nine paintings and twenty-three sculptures chosen to represent the art of the US at the American National Exhibition in Moscow, a major episode in the history of the cultural Cold War. Shahn’s work was selected by a jury of four specialists that included the realist painter Franklin Watkins and the abstract sculptor Theodore Roszak, while the exhibition was jointly organised by the USIA and the State Department. Once again, a plurality of artistic styles was identified as key to the success of the exhibition in terms of its propaganda goals. Rather than tailoring the display towards Russian or American tastes, it instead aimed to ‘needle’ Soviet visitors and make their ‘mouths water’ through the exhibition of freedom of expression in contrast to the formulaic nature of socialist realism.64 Yet although the exhibition was regarded as another victory for US cultural diplomacy, the controversy stirred up by conservative artist groups would have long-term consequences back home. Suspicion over the political records of some of the artists featured in that exhibition led Shahn to be subpoenaed in 1959 to appear, along with Philip Evergood and Jack Levine, before the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee. While the American National Exhibition would continue in Moscow with Parable in place, the committee’s attempt to foil the government’s promotion of modern art would not be in vain. By pleading the fifth amendment before congress, Shahn automatically became ineligible to be included in future state-funded international exhibitions, bringing an end to his brief but successful career as an unwitting propagandist for America’s Cold War.