To me, one of the most fascinating aspects of a painting which I like is that it is an unique expression or statement of an artist’s ideas and emotions communicated through colour, shape and texture, by him to me, in a form which I can hold, and keep, and own, and live with, and use, and enjoy, and perhaps with time to get to know and understand. This knowing of a picture should always be a challenge …

E.J. Power, 19591

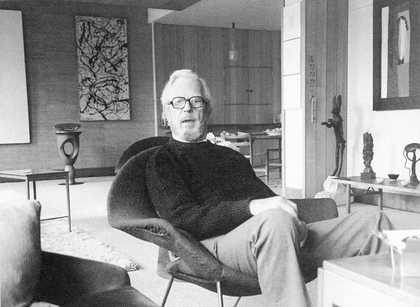

Fig.1

E.J. Power in his flat at 37 Grosvenor Square, London, c.1979. In the background can be seen part of White Fire III 1964 by Barnett Newman, Fish 1963 by Constantin Brancusi, and Untitled 1948 by Jackson Pollock. On the side wall can be seen part of Interior 9AG 1972 by Howard Hodgkin, as well as a standing hare by Barry Flanagan.

Photo © Ian McIntyre

E.J. Power (1899–1993) (fig.1), known always to his friends as Ted, was one of the great collectors of post-war international art. From the mid-1950s, when Britain was slowly emerging from years of austerity and isolation from developments in art abroad, Power sought out the newest and most radical art he could find, in Paris, New York and London. Teaching himself to discern what moved him and refining his eye for quality, he bought great works by such artists as Dubuffet, Jorn, Tàpies, Rothko, Pollock, Kelly and Barnett Newman, at a time when other British collectors and most museums and commercial galleries knew next to nothing about them. He kept abreast of the latest trends, and was a friend to many artists. He bought with passion: of Dubuffet, a painter he admired enormously, he acquired over eighty works in the period 1955–60 alone. Above all, he bought in a spirit of enquiry. As early as 1956, in the catalogue of an Arts Council exhibition of works from Power’s collection presented anonymously as New Trends in Painting: Some Pictures from a Private Collection, curator and critic Lawrence Alloway wrote of Power’s ‘experimental’ attitude towards art: ‘This collector … may buy a picture to find out what he really thinks about it. He buys new work while the paint is still wet, while the aesthetic with which to describe and evaluate it is still in the making … This anonymous collector works, one cannot help guessing, in the spirit in which his artists paint – impulsively, experimentally, to see what will happen.’ The result, Alloway said, was a collection that was ‘unique in England and impressive anywhere.’2

Nothing in Power’s early life can be said to have foreshadowed his later passion for art – except perhaps his determination to be at the forefront of his chosen field. He was born to Irish parents in Clonfort, County Galway, and lived on the family farm until 1907 when his father, an army sergeant, was transferred to mainland Britain. His parents separated, and in 1910 his mother took the family of four children to Manchester. It seems that the use of Morse code to arrest the infamous Dr Crippen on board a transatlantic liner in the summer of 1910 sparked the young boy’s imagination, and helped shape his conviction that radio was the thing of the future. As soon as he left school he enrolled on a short private course to study radio, and then, still aged only sixteen, joined the navy as a wireless operator. Over the next few years he continued to study and gain practical experience of radio while at sea, before setting up as a manufacturer of crystal sets and transformers. In 1924 he married a young wigmaker and apprentice hairdresser named Irene Bevan, known always as Rene, with whom he was to have four children. For a period he worked as chief engineer for McMichael Radio, but then left to establish his own business in Slough, repairing wirelesses and manufacturing inexpensive radio receivers.

In 1929 Power decided to join a family friend named Frank Murphy in setting up a new manufacturing firm. Unlike Power, Murphy had a little practical experience of radio manufacture but believed that he could break into the market by producing reliable, competitively priced sets that performed well and were, above all, simple to operate. Murphy Radio, in which Power was a partner and chief engineer, was pioneering in its business philosophy, engineering and cabinet design: every aspect of the company’s activities – from the layout of the factory at Welwyn Garden City to the design of the cardboard boxes used to package the wirelesses – was scrutinised and evaluated afresh by Murphy and Power in the firm’s early years. Following Murphy’s resignation, Power became chairman of the company in early 1937, and under his guidance, the firm prospered and retained its reputation for good-quality engineering and innovative design. During the Second World War, Murphy Radio entered the field of military communication, developing high-performance radar valves. Thereafter, its electronic division continued to produce military, as well as medical and acoustical equipment. Expanding into the field of television manufacture, Murphy Radio enjoyed a boom period in the 1950s. The company had been floated on the stock market in 1949 and Power was now a wealthy man. By 1962, however, he was convinced that television manufacturers had to combine into fewer, larger units, and he allowed Rank Organisation to buy control of the company. In his retirement, Power was able to devote more time to collecting art, already an absorbing passion.

Power acquired his first modern paintings in 1951. In Ireland on a golfing holiday he visited Victor Waddington Galleries in Dublin, and there bought paintings by Daniel O’Neill and Jack Yeats.3 Advised by Waddington the following year that there was to be an exhibition of O’Neill and another Irish painter named Colin Middleton in London, Power duly went and bought four more works at the gallery Arthur Tooth & Sons.

It was on this occasion that he met one of the young directors of Tooth’s, Peter Cochrane, who was to become a life-long friend and play an important role in helping him build his collection. Cochrane would discuss possible purchases with Power, sometimes accompany him on trips to galleries abroad, and deal with the many practical matters relating to the payment and transport of works. When buying for Tooth’s in Paris or New York, Cochrane and another partner named David Gibbs were keenly aware of what might interest Power, and often bought with him in mind. Power would be invited to see the best of the gallery’s purchases as they arrived, and paid only 10 per cent above what the gallery itself had paid. Power bought from other galleries, notably Gimpel Fils, but Tooth’s was, in effect, his main agent for buying paintings from abroad through the most important phase of his collecting.

Tooth’s records show that Ted Power’s early buying was catholic. In 1953, for example, he bought two more O’Neills, a Sickert, a Sisley and a flower piece by Matthew Smith. However, towards the end of that year he wished to try newer art and asked Cochrane to buy some abstract works for him. By 1954 Power was beginning to buy in large numbers: the Tooth records alone reveal fifty-four purchases made in that year.4 Although they included works by great names – a Vuillard of 1890, and a Picasso of 1953 – the majority were by lesser-known contemporary French artists.

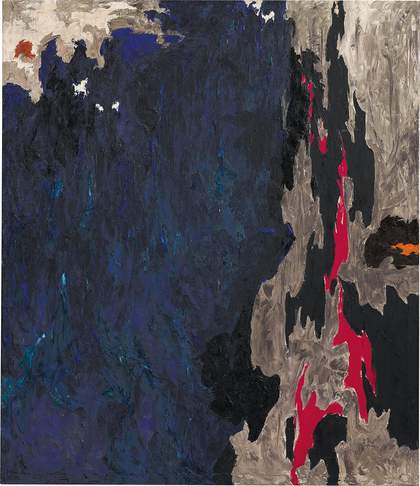

Fig.2

Clyfford Still

No.21 1948

Private collection

Purchased by E.J. Power in January 1957

© ARS, New York 2019

Fig.3

Jackson Pollock

Unformed Figure 1953

Private collection on loan to Museum Ludwig, Cologne

© ARS, New York and DACS, London 2019

Photo © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

The shift in Power’s tastes towards American abstract expressionism began after the important exhibition of modern American art held at the Tate Gallery in January–February 1956. The show contained relatively few truly contemporary works but it did have some major pieces by de Kooning, Still, Rothko and Pollock, and had a great impact on British art.5 In 1956 Power bought works by Sam Francis, an American artist then living in Paris, and also a Rothko of 1949. In January 1957 he bought Banners of Spring 1946 by Jackson Pollock and No.21 1948 by Clifford Still (fig.2). In August he bought de Kooning’s Woman of 1955, two Rothkos and a Kline. In January 1958 he acquired another Still, two Klines and two more Pollocks, including the magnificent drip painting Unformed Figure 1953 (fig.3). Power himself did not go to New York until 1964, and his American paintings were, with very few exceptions, bought by Peter Cochrane or David Gibbs, who acquired them in order to sell on to Power.6

Power had no interest in self-publicity, and preferred not to draw attention to his collecting. From the mid-1960s he lent works to exhibitions only anonymously, and although he welcomed many artists and collectors to his home to see his paintings, the full scale and importance of his collection was not appreciated even inside the circle of his friends and acquaintances. In the mid to late 1950s, however, he allowed parts of his collection of contemporary art to be exhibited, first in a touring show organised by the Arts Council in 1956–7, then at the ICA in 1958, and finally in a small display at Norwich in 1959. (Only in the case of the ICA show, however, was his name revealed.) Power agreed to these exhibitions in order to help make the radically new type of art he liked better known – or, as he wrote in the Norwich catalogue, ‘in the hope that there may be some among those who come to see them who will be receptive, rather than intolerant, and will allow the pictures themselves a chance to exert their real authority, and thereby share with me some of the exhilaration and pleasure I have found in them’.7 He may also have felt it important to support the efforts of those relatively few institutions prepared to champion contemporary international art. He later commented, ‘I did those early exhibitions because I was the only modern collector in England. It sounds terribly vain. I don’t like the “I’m first” business. I’m only saying it because in those days it was important for the ICA and the Arts Council to be recognised as having a modern outlook’.8

Power’s recent American acquisitions were among the stars of the show organised by Lawrence Alloway for the ICA in March–April 1958, Some Paintings from the E.J. Power Collection – a show that consisted of eleven works in total by de Kooning, Dubuffet (represented by the recently acquired Large Black Landscape 1946), Tàpies, Kline, Pollock, Rothko and Still. These were the artists that Power and Alloway evidently felt were the most important in the contemporary scene. The show predated by a year the exhibition The New American Painting – organised by the Museum of Modern Art and held at the Tate Gallery – which signalled the supremacy of New-York based art over the School of Paris, and to which Power was the sole British lender. He also made an important, but, as ever, anonymous, contribution to the costs of the fully illustrated catalogue.9

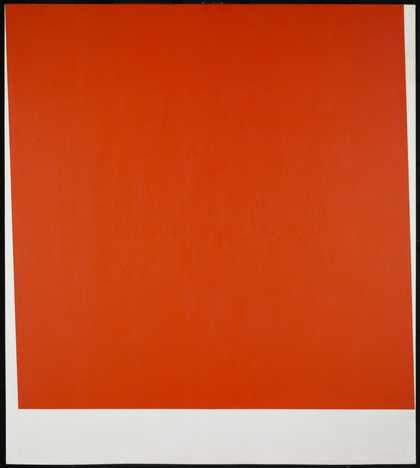

Fig.4

Ellsworth Kelly

Broadway 1958

Oil paint on canvas

1982 x 1767 x 28 mm

Tate T00511

© Ellsworth Kelly

Not included in the 1959 Tate exhibition but already strongly represented in Power’s collection was an American hard edge abstract painter named Ellsworth Kelly. Kelly – who lived in Paris between 1948 and 1954, and had exhibited at the Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in 1956 and 1957 – had sold a few paintings, including one to the Whitney Museum of American Art; but nothing anticipated the success of his show at the Galerie Maeght, Paris, in November 1958. Power happened to be in Paris with Peter Cochrane at the time, and together they chose no less than eight canvases by this relatively unknown artist, including Broadway 1958 (fig.4). According to the story told to Kelly by Alloway, Power was so excited by the show that he invited Alloway and his wife to come to Paris and see the works at Power’s expense. On his return to London, Power was still not satisfied, and attempted to acquire three more works from the show.10

Fig.5

Barnett Newman

Adam 1951, 1952

Tate T01091

© ARS, New York and DACS, London 2019

An American artist with whom Power developed a particularly close friendship was Barnett Newman. Newman was represented in the 1959 Tate exhibition by three works, one of which was Adam 1951, 1952 (fig.5), which was acquired by the Tate in 1968. In December 1959 David Gibbs, then an independent dealer, bought the companion work Eve 1950 directly from Newman with a view to selling it to Power. A little later, in March 1961, he also bought for Power White Fire I 1954. Power’s son Alan, who visited New York on business, had in the meantime become friends with Newman; and in 1964 bought Uriel 1955, from him. After the painting had been shipped to England, Newman became nervous about the necessary restretching of the eighteen feet wide canvas, and Alan persuaded him to come to London to oversee the work. Newman and his wife Annalee then med Ted and Rene, who threw a party for them and showed them London.11 Shortly afterwards the Powers went to New York on what was their only trip to the city, and spent time with Barnett and Annalee. Power admired the newly completed painting White Fire III 1964 in the studio, and prevailed upon the artist to let him buy it, even though no one else had yet seen it. Although Power and Newman met each other only on a few occasions thereafter, they corresponded frequently and had the highest regard for each other.12

In 1959 Power and his wife moved from Welwyn Garden City to a large flat in Grosvenor Square, London, which they had refurbished by Dick Russell. With its hidden lighting system, plain wooden panelling and large open spaces, it was designed to suit Power’s modern collection. Relatively few works could be displayed there, but artists who visited the flat in the early days recall the impact made upon them by seeing there single works occupying whole walls in a domestic environment.13 Power experimented with different arrangements of works in his flat (see fig.1) but in his last years visitors could expect to see at the far end of the living room a stunning grouping of Newman’s White Fire III, Untitled 1948 by Pollock, and Brancusi’s Fish, one of the very few major pieces by the Romanian sculptor held in private hands in England.

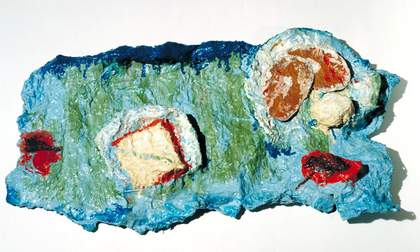

Fig.6

Claes Oldenburg

Counter and Plates with Potato and Ham 1961

Tate T01239

© Claes Oldenburg

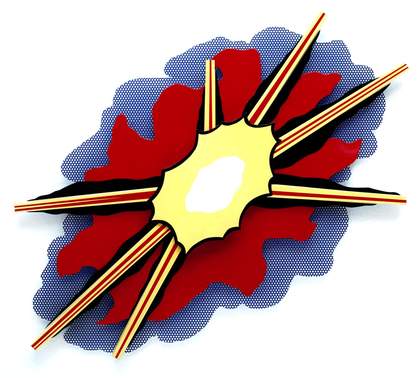

Fig.7

Roy Lichtenstein

Wall Explosion II 1965

Tate T03083

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

During the 1960s, Power continued to buy modernist works of an earlier period; but, with a few notable exceptions, he tended to avoid the great names from the first part of the twentieth century, focusing instead on lesser known and relatively undervalued artists such as the Italian Futurist Giacomo Balla and the Russian Natalya Goncharova. Increasingly, however, Power’s collection centred on contemporary American art. In terms of both quality and quantity, it was by and far away the most distinguished collection of its kind in Britain. It is difficult to establish now exactly what he acquired, but it is known that in 1964–5 he bought Counter and Plates with Potato and Ham 1961 (fig.6) by Oldenburg, Tex! 1962 and Wall Explosion II 1965 (fig.7) by Lichtenstein, The Space that Won’t Fail 1962 by Rosenquist and Soup Can 1964 by Warhol.14 He was to own a number of major early Warhols, including Troy 1962, Blue Electric Chair 1963, Flowers 1963, and Merce 1963. As ever, his purchases revealed the catholicity of his taste, and he bought not only pop art but also such colour field painters as Morris Louis and Ad Reinhardt, and the hard edge painters Josef Albers and Kenneth Noland.

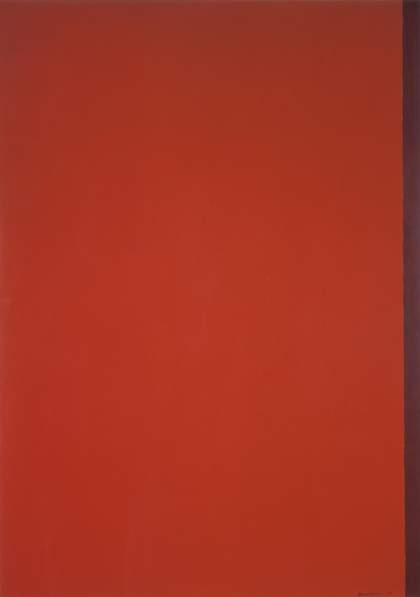

Fig.8

Barnett Newman

Eve 1950

Tate T03081

© ARS, New York and DACS, London 2019

Although Power continued to buy until the very last years of his life, and kept up to date with the latest movements in art, he no longer seriously attempted to collect the best of current work. The ending of his phase in collecting coincided with his appointment in 1968 as a Trustee of the Tate Gallery. As early as 1962 Power had attempted to strengthen the Tate’s holdings of avant-garde British art by donating a group of works by Turnbull, Stroud and Plumb, artists who had taken part in the 1960 Situation exhibition, together with Broadway by Ellsworth Kelly. During his seven-year trusteeship, Power argued with fellow Trustees twenty years his junior for a more adventurous acquisition policy, and continued to supplement the Tate’s purchases by gifts of work by young artists. In 1980 he allowed the Tate to purchase at a reduced price a group of important works including Monsieur Plume with Creases in his Trousers (Portrait of Henri Michaux) by Dubuffet and Barnett Newman’s Eve (fig.8), which are among the highlights of the post-war collection.

When Power was asked, near the end of his life, what he thought art was, he replied using a scientific vocabulary that came naturally to him ‘transmission of energy’.15 Certainly, he expected art to move him both emotionally and intellectually, and he sold works that failed to do so or which he felt had no more to offer him. Artist friends recall with affection not only his ability to discriminate the good from the bad, but also his unwavering belief in the vital importance of contemporary art. Why such discrimination and belief were so rare among British collectors at the time is hard to explain;16 but the fact remains that Ted Power was a pioneer in his collecting, whose adventurous purchases of avant-garde international art and quiet support of younger British artists, and determination to trust his own judgement and not to be bound by conventional tastes, made him an unique figure in the history of post-war British collecting.