In 1941 Tate Gallery Director John Rothenstein published his short essay ‘Painting in America’ in the British literary journal Horizon.1 It appeared alongside a poem by English-American writer W.H. Auden about the American novelist Henry James, giving the issue something of an Anglo-American theme. The journal’s Editor, Cyril Connolly, used his editorial to call for ‘better communication between the artists and intellectuals of the two countries’.2 Rothenstein’s article, however, begins with a rather more equivocal anecdote. He recalls discussing the state of American art with a group of artists in upstate New York two years earlier. ‘We were leaning over the parapet of the Groton Dam, New York, four painters, of whom [artist] George Biddle was one,’ he recounts.3 Biddle had claimed that American art was ‘so vital and abundant, it could get along without the best American artists’. Rothenstein reply was typically quick-witted. ‘And no doubt the best American artists manage equally well without American art,’ he replied.

It was a response that, on reflection, Rothenstein regretted: ‘My observation was approvingly received by all except George Biddle; naturally enough, seeing as they had claim to be counted among the best American artists,’ he recalled. ‘As soon as I had spoken I knew that George Biddle was right.’4 The anecdote signals Rothenstein’s enthusiasm for American work in the years before the Second World War. He understood interwar America to have experienced nothing less than ‘the vast awakening of an entire, vast people to art’.5 The mass audience achieved through the Works Projects Administration (WPA), conceived as part of the Federal Art Project to provide work for artists during the Depression, was one development that he especially admired. He also understood American art to have manifested, in these years, a more profound social transformation, and to point towards its future possibilities: ‘During the nineteen thirties a great and legitimate pride in American achievement became tempered by a clearer recognition of the immensity of the obstacles which she had still to overcome.’6 This new ‘national outlook’, Rothenstein believed, prompted artists to understand ‘themselves as Americans, and [they] sensed their destiny from then onward to be part of the American destiny’.7

Rothenstein’s Horizon essay appeared at a moment when strengthened cultural relations were a matter of urgent political significance. Connolly’s own introduction to the Horizon issue emphasised the mutual nature of such relations, noting that ‘there is something to be gained by sending some of our nightingales to America, but far more by inviting some Americans here’.8 To this end, he suggested that the British government invite about one hundred ‘representative American writers, painters, photographers, editors and artistic directors to visit England’. Connolly was even ready with a list of suggestions, which included such diverse figures as Anglo-American comic actor Charlie Chaplin, writer and cultural philanthropist Lincoln Kirstein, historian and philosopher Lewis Mumford, photographer Walker Evans and writer John Steinbeck. As Connolly explained, such a campaign would further mutual understanding in the darkening context of the current war. ‘An island fortress must always be on guard against provincialism,’ he explained. ‘The visit of such Americans would not only bring friendship and hope to our garrison, but would let some daylight in.’9

Rothenstein’s own involvement in American art was also shaped by the politics of international relations, both during the war and in its wake. This essay will explore the origins and development of Rothenstein’s distinctly national view of American art, and how his unique point of view helps contextualise the American works acquired by the Tate Gallery during his directorship, from 1938 until his retirement in 1964. Rothenstein’s agency here was, it should be said, far from complete. He had limited influence over the content of touring exhibitions, was often beholden to the preferences of the museum’s trustees for major acquisitions, and benefitted from the astute input of trusted colleagues.10 Yet I would argue that Rothenstein’s expansive American networks and serious engagement with the art of the United States still had a considerable – and seldom acknowledged – impact on the Tate collection that set its direction for decades to come.

The Tate Gallery’s turn to abstract expressionism was understood to be central to Rothenstein’s achievement by those across the Atlantic. According to Art Institute of Chicago director Daniel Cotton Rich, Rothenstein had ‘completely knocked the stuffiness out of that veritable institution, staging a series of brilliant exhibitions, and acquiring excellent contemporary works, including examples of American Abstract Expressionists.’11 The stature of abstract expressionism was clear by the mid-1950s, but hardly secure – and the Tate Gallery’s acquisition of works by Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock in 1959 and 1960 respectively was undoubtedly progressive, if not quite pioneering. Given the museum’s historically paltry acquisitions budgets, limited gallery space and the escalating prices of international modernism in the late 1950s, the efforts of Rothenstein and his colleagues to acquire work by key figures of American painting confirmed the museum’s commitment to post-war abstraction.

Art historian Lisa Tickner has claimed that it was only after Rothenstein retired that the museum developed an ‘increased identification with recent and contemporary art’.12 Yet I suggest that the broader range of styles and movements seen in the artworks acquired by Tate in the years after Rothenstein’s retirement reflects less the changing visions of its directors than it does their desire to build on the foundations of his tenure, and to continue Tate’s commitment to assembling a representative collection of modern painting and sculpture. There is some truth to Tickner’s characterisation of Rothenstein’s ‘views on modern and abstract art’ as ‘conservative’, but it should not obscure his role in the acquisition of many of the museum’s most important works of post-war modern and abstract art from the United States.13 As Adrian Clark has shown in his landmark study of Rothenstein’s career, he was ‘the first Director of Tate to have a serious interest in and understanding of modern art’.14 These were perspectives that he had developed over several decades of engagement with American art through a uniquely British prism, viewpoints far more complex and expansive than the apparent ‘triumph’ of New York School abstract painting.15

Learning American: Rothenstein before Tate

At the age of twenty-five, four years after graduating from the University of Oxford, Rothenstein moved to the United States. He accepted an appointment as a lecturer in the department of art history at the University of Kentucky, Lexington in 1927, and stayed there for one academic year. In his autobiography Rothenstein recalls being told soon after his arrival that he had ‘sure learnt American fast’.16 Despite succumbing to such hillbilly clichés, Rothenstein became a keen student of American art. According to the press coverage of his arrival, it was his ‘interest in America and Americans’ that was ‘principally responsible for his coming to this country’.17 Under the influence of his painter colleague Edward Fisk, Rothenstein discovered the work of American modernists, including Fisk’s friend Charles Demuth.18 Painters Albert Pinkham Ryder and Thomas Eakins also caught his attention, and in a 1927 lecture Rothenstein praised these two artists for showing ‘less foreign influence than others of their class’.19 Despite his own primary expertise in English art, and perhaps because of English art’s own distinction from the dominant canons of French modernism, Rothenstein’s understanding of American art equally emphasised its capacity to express the particularities of national character.

In his little-known 1930 article ‘A Note on Thomas Eakins’, which was probably based on such lectures, Rothenstein differentiated the unjustly ‘disregarded’ Eakins from those ‘American painters with European reputations [who] have been exalted by their own countrymen rather to the detriment of those who have stayed at home’.20 His interest in American artists such as Eakins and Ryder was refracted through the prism of parochialism that Rothenstein understood to be diminishing the reputation of American artists among Americans themselves. In ‘Painting in America’ he reflected:

My audiences were evidently pleased by the news – for it was news to many of them – that American painters had flourished who remained in their own country, and whose work merited, nevertheless, the most serious consideration. Yet these audiences also found delicate means of making me aware that since ‘art’ was understood to be my subject they regarded my eulogies of these two American painters as digressions, needlessly polite.21

Another anecdote reinforces the same widely held prejudices. ‘We signed on for your course to learn about artists, not Americans’, he recalls a group of his students complaining.22

In Lexington, Rothenstein’s ties with the United States also found a more permanent, personal bond: there he met and later married Elizabeth Kennard Smith, a student at the University of Kentucky who had also studied at the Art Students League in New York. In 1928 Rothenstein accepted a role as Assistant Professor in the newly established Department of Fine Arts at the University of Pittsburgh. Yet Rothenstein was unhappy in Pittsburgh, complaining that the booming industrial city was ‘odious’ and that his employer was like an ‘office which students attended for the sole purpose of securing the degrees necessary for their several careers’.23 Reflecting later on his time at the university, he explained that he was also ‘disquieted at the thought of teaching a course in which he had no degree’ – and returned to London to begin his doctorate after only a year in the department.24

Rothenstein’s time in the United States fostered a vision of American art that always extended beyond the galleries and museums of New York City. ‘There exists no centre, such as London,’ Rothenstein claimed in 1941; instead, ‘artists are widely distributed over an immense country’.25 In Pittsburgh, Rothenstein attended the Carnegie International, the major international survey exhibition, and here he again noticed that the contributions of international artists were of much greater interest to local audiences than those of the Americans.26 His focus on a distinctly American tradition developing independently of European movements meant that he was especially attentive to the nation’s folk traditions, and he visited the studio of self-taught artist John Kane, and even drafted an article on his work – though it failed to be accepted for publication.27

Fig.1

John Kane

Old Clinton Furnace no date

Private collection

Rothenstein singled out Kane’s undated oil painting Old Clinton Furnace (fig.1) for special attention in his review of the 1928 Carnegie International.28 He observed, ‘The present exhibition shows that American painting still tends to express itself in the European tradition’.29 Old Clinton Furnace was, for this reason, ‘the most striking exhibit in the American section’, and Rothenstein praised its ‘directness of perception and the entirely unaffected simplicity of outlook that belong to the primitives of all ages’. He observed further that ‘The perspective is faulty, the drawing is weak in parts, the colour obvious. But this striking directness and an absence of the truculence which pervades so much contemporary art gives Old Clinton Furnace a large measure of significance and charm.’30 Rothenstein’s account of Kane’s work confirms his efforts to see in American art the archaic, primitivising qualities that English critics had identified as the most praiseworthy properties of European modernism.31

Rothenstein’s efforts to draw American art into the histories of international modernism intersect with his more straightforward engagement with transatlantic geopolitics.32 In Lexington, Rothenstein would speak publicly about Anglo-American relations. In a 1927 lecture titled ‘Great Britain’s Foreign Policy’, he sought to defend to his American audience allegations of negative British attitudes towards the United States: ‘Some of England’s former world powers have passed from her to this country … Naturally this would cause some dissatisfaction among a certain group of English, yet this group is so small when compared to the number who hold a good and sympathetic attitude towards your country.’33

Rothenstein and his wife returned to England in 1929, and Elizabeth began to demonstrate her own commitment to such efforts too. ‘I believe that friendship between England and America really is the only sure foundation of world peace,’ she told a Leeds newspaper at the height of the Depression, ‘and so I wish that people here would bear with America in her hour of crisis’.34 In 1937 Rothenstein presided over a meeting of the League of Nations’ Union in Sheffield, chairing discussions about the responsibility of Britain and the United States to support China in the Second Sino-Japanese War.35 A more populist gesture towards American culture might be detected in Rothenstein’s organisation of an exhibition of Walt Disney’s drawings and animation cels in 1935.36 Whether dabbling in transatlantic politics or validating American popular culture, such interests would colour Rothenstein’s work with American art in the years ahead.

Rothenstein and the special relationship

Rothenstein’s engagement with American art in the context of transatlantic cultural diplomacy persisted through the 1930s, and would eventually acquire more urgent political significance in the shadow of the Second World War.37 After stints as director of Leeds City Art Gallery (1932–4) and the Graves Gallery in Sheffield (1934–8), Rothenstein’s formative engagement with American art was able to find expression when he was appointed director of the Tate Gallery in May 1938. Among Rothenstein’s first changes at the museum had been to rehang the displays in rooms XXI, XXII, XXIV and XXV, adding work by the American-born James Abbott McNeill Whistler and others, such that the galleries would reach a ‘proper climax of the contemporary modern painters’, as a critic for the Observer described it.38 Even if this critic thought that the selection still revealed Tate’s modern collection to be ‘cautiously conservative’, Rothenstein’s tilt towards the modern indicated his future ambitions for the collection and its display.39

American art had a limited presence in London in the 1930s, but it was not invisible. Many of the artists Rothenstein knew from his time in the United States were included, for instance, in Contemporary American Painting at Wildenstein & Co. in May and June 1938. The exhibition included works by artists including Biddle, Kane, Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, Edward Hopper, Reginald Marsh, Leon Kroll, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, John Sloan and Max Weber. As its catalogue essay by critic Henry McBride emphasised, the exhibition’s works presented London with an image of modern American life, postcards from a place not yet threatened by war. Rothenstein had met several of the artists that were featured in the exhibition, and many others would have been familiar to him from the Carnegie International ten years earlier.

Fig.2

George Inness

The Delaware Water Gap 1857

National Gallery, London

Although it was later transferred to the National Gallery, in 1939 Tate accepted a gift of George Inness’s The Delaware Water Gap 1857 (fig.2), a misty landscape whose luminous, proto-impressionist tendencies sat comfortably with the museum’s collection of works by English artist J.M.W. Turner.40 Publicising the acquisition, Rothenstein stressed how much he ‘admired American art’, and lamented that there was ‘“next to nothing” of American painting’ in the Tate collection.41 But American newspapers also covered Tate’s contemporary refusal of a portrait of the Duke of Windsor by ‘famed American painter John Sargent’, a decision that Rothenstein explained was reached ‘purely on its merits as a portrait’ rather than for any ‘political motives’.42 In 1931 Tate Gallery’s trustees had declined two works by Arthur Davies left to the museum by Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) co-founder Lillie P. Bliss, a decision that the New York Times reported as ‘an implied aspersion on one of the best loved of modern American painters’.43 American interest in such decisions as a sign of validation – or otherwise – would persist as the Tate Gallery pursued American works more actively in the post-war years.

Rothenstein’s new orientation towards American art acquired particular relevance during the Second World War. As Tate packed up its collection for safe wartime storage in late 1939, Rothenstein headed to North America. His trip was prompted by an invitation to speak at the National Gallery of Canada, but he also used it to embark on a lecture tour across Canada and the United States.44 The topics of his lectures varied, and included presentations in museums in Chicago, Detroit and New York.45 While on this trip Rothenstein also proposed a scheme for Canadians and Americans to undertake six-month work placements at the Tate Gallery. According to the New York Times, it was hoped that the programme would benefit ‘the scholarly tradition of transatlantic museums’, emphasising the bonds and continuities that – whatever the limited realities of inter-institutional relations across the Atlantic – acquired new importance in the context of wartime cultural diplomacy.46

Adrian Clark has emphasised the internal unrest that Rothenstein’s seven-month absence from the museum provoked.47 But Rothenstein’s extended tour can be understood to have helped demonstrate shared cultural values between Britain and the United States, especially in the context of Britain seeking to persuade America to intervene in the Second World War.48 A letter from Museum of Fine Arts Boston director George Edgell introducing Rothenstein to Frederic Delano, Chairman of the Smithsonian Gallery of Art Commission (and uncle of President Roosevelt), outlines another unfulfilled initiative designed to foster transatlantic cultural diplomacy:

I had a talk with him today and he had a most interesting scheme, purely, of course, in the tentative stage, of possibly Britain’s lending to this country some of the great masterpieces that normally would be in the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery but are now hidden away for safety’s sake during the war. Of course, what American museums would not shout with joy at the prospect. What, however, would be the reaction of the Government? Is it a thing in which the Government itself might be interested?49

Although this plan did not come to fruition, Rothenstein actively used the trip to promote transatlantic cultural bonds. While in New York, Rothenstein took responsibility for overseeing the installations of Henry Moore’s Recumbent Figure to the Contemporary British Art exhibition at the New York World’s Fair of 1939.50 The Contemporary Art Society in London had also charged Rothenstein with presenting a work by British painter Stanley Spencer to the city’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. When a curator at the museum indicated that it was ‘not at all the kind of thing we are acquiring’, the work was instead offered to and accepted by MoMA.51 The Metropolitan Museum’s refusal is a reminder that, no less than was the case for American art, British art occupied a secondary position in the emerging modernist canon.

Rothenstein’s visit to North America allowed him to engage with several significant American artists. In New York he met with Kenneth Hayes Miller, artist and teacher at the Art Students League of New York, whom Rothenstein regarded as having exerted an influence ‘quite disproportionate to the smallness of his talent’.52 He approved, on the other hand, of the work of John Sloan, whom he regarded as a ‘fuller-blooded, less capricious, less sardonic [Walter] Sickert’.53 Rothenstein recalls that he reserved one of Sloan’s paintings of New York’s Sixth Avenue for the Tate collection, although he does not state which painting it was and there is no record of such a work being considered for acquisition in London.54 Elsewhere, Rothenstein had expressed his surprise that Sloan’s practice had developed without the artist ever having travelled abroad, indicating that he was as attentive to the central position of expatriate experience in the development of American painting as he was to its exceptions.55

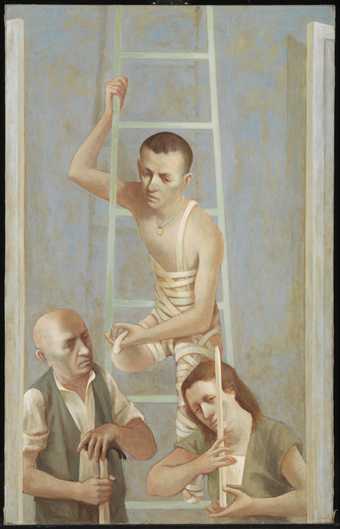

Fig.3

Charles Burchfield

Freight Cars in March 1933

Tate N04833

© reserved

In Buffalo, Rothenstein visited the studio of American scene painter Charles Burchfield, where he again ‘earmarked two fine water-colours for the Tate’.56 Tate had accepted Samuel Courtauld’s gift of a work by Burchfield in 1936 (Freight Cars in March 1933; fig.3), but there is again no record of these watercolour works being considered for acquisition in London. ‘Burchfield is a more various John Nash’, Rothenstein later explained to a British audience.57 Elsewhere, he cast Thomas Eakins as a ‘Pennsylvanian [Gustave] Courbet’.58 In understanding American painting from the vantage point of European art, Rothenstein’s efforts to validate American art could occasionally fall victim to the same parochialism that he understood to be limiting its recognition.

Fig.4

Winold Reiss

The History of Cincinnati 1931

Union Station, Cincinnati

Photo © Meg Vogel, Cincinnatti Enquirer

Rothenstein had arrived in Cincinnati to the sight of Winold Reiss’s 1931 mosaics at Union Station (fig.4), an example of art deco muralism depicting the triumphant progress towards modern industrial America.59 Such public projects had a powerful impact on Rothenstein’s view of the American artistic scene. ‘Art seemed to have escaped from the studio into the railway station, the law court, the town hall, and the post office,’ he wrote.60 On his return to Britain, Rothenstein actively promoted Roosevelt’s cultural policies, writing in 1941: ‘President Roosevelt’s legislation – perhaps the most momentous art legislation in history – represents a very striking attempt by a great modern state to assume responsibilities towards the arts on a scale in any way commensurate with its resources.’61

Fig.5

Symeon Shimin

Contemporary Justice and the Child 1940

Great Hall, Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

Photo © Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Rothenstein’s interest in British mural painting extended to the American context.62 In addition to his visit with muralist George Biddle in Croton-on-Hudson, he saw Symeon Shimin’s new mural for the Justice Department in Washington D.C. (fig.5), and was ‘particularly impressed by the mastery’ of its creator.63 He attended the Corcoran Museum’s Forty-Eight States Competition, for which post office mural designs were submitted for sites across the United States. Writing a few years later, Rothenstein described the show as ‘one of the most inspiring exhibitions I had seen’.64 Although he thought that the works on display were of varying quality, Rothenstein saw in this exhibition an emerging national school:

Even the least study there, gave utterance, however faltering, to what the best so resoundingly proclaimed: that there was a new spirit abroad in America, a spirit by which artists were also moved and willingly expressed in terms which all could understand … It would be absurd to claim success for the artists represented in the Forty-Eight States Competition where Hogarth, Reynolds, Gainsborough, Lawrence, Whistler, Eakins and Ryder failed, but they are, I believe, attempting to interpret with a more conscious purpose their country’s sense of its past, present and future.65

Rothenstein selected a group of Federal Art Project mural studies for Tate, but upon his return, the Treasury refused to provide the ‘no more than a hundred dollars’ needed for their purchase.66 It was an acquisition that Rothenstein evidently understood in relation to transatlantic relations on the cusp of the Second World War.67 He later recalled that ‘United States Government agencies were ready with nation-wide announcements in the press and over the radio that direly threatened Britain had made this generous gesture to American art’.68 Federal Art Project staff wrote to Rothenstein to acknowledge his efforts. ‘I am taking the liberty of forwarding a copy of your letter to each of the artists concerned’, wrote Edward Rowan from the Federal Art Project in relation to the failed art acquisition, ‘A problem of this kind seems very small and insignificant in comparison with the real distress which all of us are feeling for democracies.’69

Rothenstein’s autobiography claims that he visited the White House while in Washington, and although Roosevelt’s papers do not indicate that he met with Rothenstein, the latter’s work certainly came to the attention of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. In August 1941 her widely syndicated ‘My Day’ column cited Rothenstein’s views on American art from his Horizon article, quoting it at length.70 Reporting on American cultural policy to a British audience that same year, Rothenstein praised ‘the vision and courage of President Roosevelt’ in supporting the arts through public commissions, claiming that:

The next step … is likely to be the evolution of a coherent continental style. Whether it will call great masters into being is another question. But it seems more probable that in the arts as in other spheres of recreation, the American genius is adapted rather to tremendous collective achievements than to the studied expression of the individual spirit.71

Again, Rothenstein’s interest in American art understood its achievements in national, collective terms. His enthusiasm for the cultural policies of the New Deal, the series of projects and programs instituted by Roosevelt during the Great Depression with the aim of simulating nationwide employment and growth, was maintained throughout the 1940s. In April 1944 he gave a slide lecture on American painting at London’s Churchill Club, introduced by Sargeant Olin Dows, and in June delivered a paper entitled ‘State Patronage of Wall Painting in America’ at the Royal Institution.72

Such interests also had an impact on the Tate exhibition programme: in 1950 the gallery exhibited samples from the Index of American Design, a collection of watercolours of furniture, ceramics, metalworks, textiles and costumes that was borrowed from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.73 Compiled from 1936 until 1942, the Index had been another product of the wide-ranging cultural impact of the Roosevelt administration.

Building on his formative exposure to American art in the 1930s, Rothenstein’s efforts to engage with American art on the cusp of the Second World War show a museum director attentive to the national tendencies of interwar modernism in the United States, and interested in the possibilities of cultural diplomacy. Although the Tate Gallery’s limited budgets precluded substantial acquisitions, this history also indicates Rothenstein’s orientation towards the art of the United States long before New York School painting began to occupy a central position in international modernism in the 1950s. Rothenstein’s more diverse understanding of American art helps explain some of the idiosyncrasies of Tate Gallery’s early engagement with American art, peculiarities that speak to a more pluralistic characterisation of post-war practice than its canons would later permit.

Post-war opportunities

In 1945, New York’s Artists for Victory group sent the Goodwill Exhibition of Contemporary American Art to Britain, to be displayed at the Tate Gallery. Invited to select one painting from this exhibition to be donated to the museum with the support of Chicago philanthropist and department store mogul Marshall Field, Rothenstein passed over works by Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis and Andrew Wyeth, and instead chose to acquire Maurice Sterne’s Mexican Church Interior 1934–5 (fig.6).74 Although the choice may now seem unlikely, Sterne was a respected American painter whose eclectic expressionist works had secured a MoMA retrospective in 1933, among other high-profile accolades. Sterne’s Mexican Church Interior undoubtedly appealed to Rothenstein’s taste for the moderate strains of modern painting, and perhaps also his Catholic faith. It is also difficult to imagine that Rothenstein was not reminded of Edward Burra’s Mexican Church c.1938 (fig.7), acquired by the Tate Gallery five years earlier.75

Fig.8

Theodore Roszak

The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952

Tate N06163

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

It was not until 1946 that Tate began receiving an annual purchasing grant of £2,000 – funds that made it possible for Tate to acquire, in 1949, its first cubist picture (Picasso’s Bust of a Woman 1909, Tate N05915). The purchasing grant was increased to £6,250 in 1953, and then £7,500 in 1954. Few works of American art were acquired over these years. Tate accepted the gift of Bernard Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948 (Tate N05956) from Lincoln Kirstein in 1950, and used the occasion of the International Sculpture Competition, which invited proposals for a sculptural monument to the unknown political prisoner, to acquire maquettes for Theodore Roszak’s Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952 (fig.8). As with his interests in mural painting, the public ambitions of the maquettes were in line with kind of social engagement that Rothenstein favoured in modern art. The Guardian reported that the expansion ‘in the representation of works of the twentieth century’ was focused on ‘British artists’ and the ‘school of Paris’ – making it ‘difficult to represent other movements as fully as was desired’.76 The Tate Gallery had built the ‘foundations of a collection of modern foreign paintings’, Rothenstein explained in 1954, but he also emphasised that the breadth of these holdings was ‘still very inadequate’.77

Even given the museum’s paltry budgets, Rothenstein’s generally cautious attitude towards abstraction must have impacted the museum’s acquisitions of New York School painting. He told an audience in 1953 that he could not see much of a future for the fine arts ‘unless something in the way of a common stock of imagery unites artist and layman once again’.78 However, Rothenstein’s views on abstraction do seem to have shifted in the mid-1950s: ‘Whatever one may think of it, abstract art is probably the most characteristic art of our time, and it is one which draws, like some mysterious magnet, many of the most considerable talents,’ he explained in a March 1955 lecture.79 Such sentiments were repeated to an audience in Florida the following year. ‘Whether one likes abstract art or not, it is the characteristic art form of the twentieth century’, he explained. ‘I think students of today have learnt more from the great abstract painters than from any others.’80

Rothenstein’s views on abstraction were equivocal: he seems to have regarded it both as a trend perpetually on the cusp of decline, and as the most representative art of the modern age. He would later explain:

Abstract art is a logical manifestation of the division of function which is industrial society’s greatest law. It is therefore not, as many hold, esoteric; it is on the contrary, a conspicuous example of specialisation. It is not only in close harmony with the procedures that distinguish most of the collective activities of modern man, but – and perhaps for this reason – it attracts a high proportion of outstanding talent.81

This alignment between industrial and artistic production meant that Rothenstein understood abstraction to be especially suited to the cultural character of the United States. ‘Your action painting requires high-strung temperaments’, he told American critic Dore Ashton in 1956, whereas ‘generally speaking, the British are more phlegmatic and work in a more relaxing atmosphere.’82

Such an estimation of the national character of contemporary American painting might well have been informed by Modern Art in the United States, the exhibition of some 125 works of twentieth-century American painting, sculpture and printmaking from the collection of MoMA in New York that was presented at the Tate Gallery in January 1956.83 The strong showing of abstract expressionist paintings in the exhibition represented, as a critic in the Times proposed, the ‘shock troops in the American invasion of painting’.84 Rothenstein was absent from the opening as he was embarking on another speaking tour across North America. The trip saw him visit more than a dozen museums, and he presented a lecture on ‘Anglo-American cooperation in the fine arts’ that was reportedly broadcast on more than 150 radio stations around the country.85 Rothenstein’s emphasis was firmly on providing international validation to American art, as a Florida newspaper report confirms:

In a thick English accent, the small man, armed with an umbrella stick, said that he thought that there was ‘quite as much’ interest in art in America as in England. ‘One of the most striking things about the United States,’ he said, ‘is the fabulous progress made by the art museums over the country. It is difficult to say who is your greatest living artist, but I think among the outstanding are Morris Graves and Birchfield [sic].’ Sir John said that there aren’t many American paintings at the Tate, though at present one exhibit from this country is being shown. ‘There is a great deal of energy and variety in modern American art,’ he said. ‘I hope to buy at least one American painting or piece of sculpture while I’m here. After I speak in New York … I plan to look around [for art objects].’86

Rather than acquiring a work by Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning – both suggestions from his colleague Ronald Alley – Rothenstein focused his attention on the work of John Marin and Arthur Dove at New York’s Downtown Gallery. The gallery’s director Edith Halpert wrote to Rothenstein in a follow-up note: ‘we are so pleased with the prospect of placing American art in the Tate Gallery that we are prepared to make a tremendous concession’.87 Marin’s Downtown, New York 1923 (fig.9) was offered at almost half price – $1,800 rather than $3,500. The work by Dove was reduced from $1,400 to $900, but ultimately not acquired. Halpert had herself publicly criticised the museum’s refusal of the Arthur Davies gift from Lillie Bliss two decades earlier, and her discount unapologetically sought to capitalise on, as she put it, ‘the prestige value of an announced purchase by The Tate Gallery of an American work of art’ for the artists she represented.88

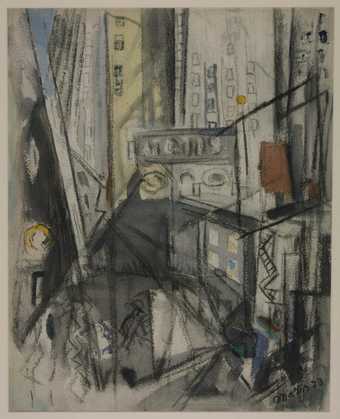

Fig.9

John Marin

Downtown, New York 1923

Tate T00080

© reserved

Rothenstein arrived back in London in late February 1956.89 As the board minutes from a meeting of the trustees in March 1956 record, he presented ‘a number of photographs and other reproductions of modern American painting which the Director had assembled in the course of his recent visit, including those of works by Marin, Burchfield, Hopper, Dove and Morris Graves’.90 Claiming Marin as America’s ‘most important modern native-born artist’, Rothenstein’s perspective coheres with the view of the field he had developed before the war, a view that was reinforced by the American emphasis of Halpert’s gallery.91 In institutional terms, this reflected less the influence of MoMA than it did the collecting focus of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, where a Burchfield retrospective had opened that January and a Morris Graves show was due to open the following month. Rothenstein’s high estimation of Marin was bolstered by the Arts Council’s presentation of an exhibition of Marin’s work at its gallery later in 1956.92

At the end of February 1956, Rothenstein wrote to Halpert: ‘I derived enormous encouragement from your interest in the possibility of laying the foundations of a collection of American paintings at the Tate.’93 He also thanked Halpert for helping him to meet American painters and sculptors, but advised that only $1,500 was available for the purchase of Marin’s Downtown, New York – and even this amount would only be available if the transaction could be deferred until March.94 Halpert agreed to the further price reduction and delay in payment.95 The cost of the work was met not from Tate’s own funds, but from those of the Bruern Foundation, a New York-based philanthropic organisation run from the Fifth Avenue offices of the Astor family.96 At the time Downtown, New York was on display at the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston, and its acquisition forced it to be removed from the exhibition to be sent to Tate.97

With the Marin acquisition confirmed, Halpert geared up to announce the purchase. ‘I should like to know whether or not this is the first official purchase of a contemporary work of American art by the Tate Gallery,’ she wrote.98 Tate advised that the museum itself would announce the acquisition in the New York Times once it went on display, but also clarified that Downtown, New York was not, in fact, the first work of post-war American art purchased by the museum.99 Interviewed by Associated Press arts editor W.G. Rogers in late 1956, Rothenstein was conscious enough of the limited presence of American art at the Tate to be able to name the four American artists (Marin, Perlin, Sterne and Roszak) whose works were acquired under his tenure. Asked to state which artists he regarded as the most distinctively American, Rothenstein resisted the idea that there was a unified American style, and rejected the idea that New York City was its headquarters. ‘But I think if I had to name names,’ he offered, ‘I’d look to the Northwest and such painters as Morris Graves and Mark Tobey.’100

Rothenstein’s distinctly national image of American art, formed through his own institutional commitments to the category of British art – and certainly at the expense of what we might now understand as the incipient internationalism of post-war painting – was shaped not only by Halpert but also by his first-hand experience with American art in the 1920s. When the Tate Gallery rehung its modern galleries in mid-1956, Rothenstein borrowed Elie Nadelman’s The Hostess 1918–23 from Sir Osbert Sitwell, one of several instances where Rothenstein used loans to supplement the museum’s meagre holdings of American art.101 But a review of these new displays in the Times noted that ‘the youthful school of abstract expressionists’ were ‘as yet unrepresented at Millbank’, and that although ‘no Jackson Pollock or de Kooning has so far been acquired by the Tate, the Director and the Trustees are unlikely to be called to account by anyone for timidity or undue caution’.102

New actions

If the Marin purchase confirms Rothenstein’s preference for the moderate and historical strands of American modernism, it is clear that Tate trustees remained more conscious of more contemporary developments. The board minutes from March 1956 record that it was only ‘after some discussion, in which various names were considered, in particular [Alexander] Calder and the members of the Action School referred to by Mr [Henry] Moore, [that] the Board decided to buy the Marin’.103 This mention of the ‘Action School’ – a corruption of the title of Harold Rosenberg’s 1952 essay ‘American Action Painters’ – suggests Moore’s role in directing the museum’s attention to more contemporary developments in American painting.104

British dealers had been rather more agile in their response to Modern Art in the United States than the Tate Gallery. Beginning in 1956, the summer exhibitions at Gimpel Fils included works by Franz Kline, Pollock and Mark Rothko. Arthur Tooth and Sons also began working with New York dealers Betty Parsons and Sidney Janis, purchasing speculatively in hopes of finding London buyers, but also borrowing work on the basis that they would take a commission on sales. Combined with the substantial freight costs for large works, such arrangements undoubtedly contributed to escalating international prices, which in turn fed price increases in New York. As art historian Jennifer Mundy has shown, Edward Power was one of the most active British collectors of such work.105 Perhaps it was with this in mind that artist and Tate trustee William Coldstream suggested, in late 1956, that the museum needed to ‘buy a little ahead of the market and before the painters had been “discovered” by the dealers’.106

Fig.10

Sam Francis

Painting 1957

Tate T00148

© Estate of Sam Francis/ ARS, NY & DACS, London 2019

Tate’s own first gesture towards abstract expressionism was rather more tentative: a modest Sam Francis work (Painting 1957; fig.10), purchased from Gimpel Fils in 1957 for 65 guineas. Praised for its lyrical colour and the artist’s debt to Turner and Claude Monet, Tate’s first abstract painting by an American remained one easily assimilated with the more familiar contexts of tachisme – the form of gestural abstraction then dominating French art markets.107 In January 1957 Tate trustee Lawrence Gowing found it necessary to check that ‘the board was still interested in acquiring American pictures’.108 Furthermore, when Gowing told the trustees that he was planning a trip to the United States later in the year, the minutes record that he was asked to be on the lookout for ‘photographs of any work by [French abstract painter] Nicolas de Stael that were available in New York’.109 The fact that Tate purchased a major abstract work by his fellow French tachiste Pierre Soulages (Painting, 23 May 1953 1953, Tate N06199) five years before any works of New York School painting reflects less the conservatism of Rothenstein and his trustees than it confirms the still unstable status of American painting in the mid-1950s.

However, a revised acquisitions committee list of foreign artists produced the following month, in February 1957, makes clear that the Tate Gallery was working towards a more substantive representation of recent American art. Among the twelve foreign artists named, Pollock was the only American painter marked as a high priority. But the secondary list included Graves, Lyonel Feininger, Edward Hopper, Francis, de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Marin, Ben Shahn, Tobey and Rufino Tamayo.110 The list of sculptors featured Calder and Naum Gabo, as well as new – if secondary – ambitions to acquire works by Ibram Lassaw and David Smith.111 In May 1957 Rothenstein reported that he was in discussion with the American Federation of Arts to obtain their assistance in ‘securing the offer of works by American artists on the priority lists’ in a way that would allow gifts to be tax deductible for American donors.112

Gowing returned from New York not with leads on de Stael, but with the sobering news of prices from the booming New York market. In October, Gowing told the trustees that the going rate for a Pollock was now around $20,000 to $30,000, and de Kooning around $7,000. Given the limits of Tate’s budgets, he suggested that the gallery enlist the help of MoMA to borrow works directly from artists, not only enabling direct purchase but providing ‘an opportunity of assessing their quality before making any purchases’.113 Rothenstein expressed his scepticism: he worried about the large amount of wall space that American painting might colonise in the already cramped galleries, as well as, more crucially, rejecting the idea that MoMA should assist, arguing that the New York museum ‘might take a less representative view’ of American art ‘than the Tate trustees’.114

MoMA’s burgeoning International Program meant that the Tate Gallery was in close contact with the museum throughout the 1950s. However, the relationship should not be overstated: a letter from August 1954, for instance, shows Rothenstein’s assistant asking whether Rene d’Harnoncourt was still the museum’s director.115 According to art historian Michael Clegg, the Tate Gallery’s curatorial approach under Rothenstein represented nothing less than a ‘nuanced response to what had become the MoMA-led orthodoxy’.116 The view from other side of the pond further helps put such interactions into perspective. ‘I do not have great faith in Rothenstein’s taste’, wrote Alfred H. Barr Jr at MoMA in an internal memo in the lead up to the 1956 exhibition Modern Art in the United States, ‘but on the other hand the Tate is by far the best place for such an exhibition, and Rothenstein seems quite willing to accept a great deal of American advice, particularly from our museum.’117

Whatever Barr’s views of his taste, Rothenstein’s rejection of MoMA’s seemingly ‘less representative’ approach to American art held on to a more complex picture of American modernism, one that found room for the realist and folk traditions with which he had engaged since the 1920s. These were interests that would persist in the margins of Tate Gallery acquisitions throughout the final years of Rothenstein’s directorship. By the end of the 1950s, however, the position of American abstract expressionism was too secure to ignore. In 1958 Tate had added several new names to the list of foreign artists it wished to acquire: sculptor Richard Lippold, and painters Philip Guston, James Brooks and Mark Rothko. Pollock, Guston, Calder and Gabo were indicated to be of the highest priority. By 1959 Pollock was still the only American painter among the priority artists, but Isamu Noguchi had been added to the list of sculptors, along with Matta (Roberto Matta Echaurren), Kenzo Okada, Seymour Lipton and Mary Callery all at a lower priority.118

In 1959 the increase of the Tate Gallery purchasing grant to £40,000 finally made it possible to seriously increase the museum’s collecting activities.119 The founding of the Friends of the Tate Gallery in 1958 opened a further fundraising stream for acquisitions, and in March 1960, this was extended to the United States with the founding of the American Friends of the Tate Gallery. American Ambassador John Hay Whitney, whose own collection would be exhibited at Tate later in the year, became president of the American Friends. Robert Lehman agreed to provide banking services to the group, while high-profile New York lawyer and art collector Allan Emil was hired to handle the legalities.120 Although problems with the financial status of the group delayed its activity, Tate hoped that the group would enable access to the same tax privileges as other American charities, in the hope that – as Rothenstein later put it – the museum might benefit from a ‘spectacular spate of gifts’ comparable to those enjoyed by American art museums.121

Beneath such optimism, however, were the challenges that the Tate Gallery faced in order to compete in a booming American art market. When trustee Robert Adeane and museum staffer Norman Reid phoned from New York in March 1959, they reported that ‘works by the most famous American artists were now almost beyond the Gallery’s resources’.122 With an evident sense of panic, they asked for permission to make purchases of works by younger artists up to a price of £1,500. The request was declined, not just for its irregularity, but because the board was also about to consider ‘a further set of suggestions brought back by the Director from Paris’.123 The anxiety over escalating prices seems to have spurred a flurry of purchases. Acquisitions of works by Guston and Brooks resulted from this trip, purchased from Sidney Janis and Stable Gallery respectively (Philip Guston, The Return 1956–8, Tate T00252; and James Brooks, Boon 1957, Tate T00253). At the next meeting, the museum confirmed the purchase of Tobey’s Northwest Drift 1958 (fig.11) from the Willard Gallery, and, at the meeting after that, Mark Rothko’s Light Red Over Black 1957 (fig.12) from the Sidney Janis Gallery.124

In the final five years of his tenure as director, and especially after the formation of the American Friends, Rothenstein worked assiduously to develop networks with major patrons and artists in America. He used an invitation to speak at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Canada as a chance to spend a few weeks ‘mak[ing] contacts with artists and dealers’ in the United States in July 1959.125 His trip was funded by the US State Department, and he met with its staff in Washington, D.C. He also visited San Francisco and Los Angeles, then a range of galleries in Arizona and New Mexico. Returning via New York, Rothenstein attended a preview of the new Frank Lloyd Wright Guggenheim Museum in October, where he reported meeting artists including Rothko, Motherwell, Guston, Brooks and William Baziotes.126

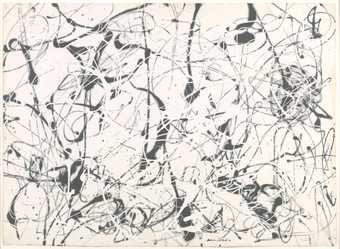

Fig.13

Jackson Pollock

Number 23 1948

Tate T00384

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

In November 1960, it was announced that the museum would acquire its first work by Pollock (Number 23 1948; fig.13). The Evening Standard leaked the news:

In the next day or two, the Tate Gallery is going to announce the purchase of an important work by Jackson Pollock … Six months ago such a thing would scarcely have been possible. One can imagine the uproar the trustees would have faced for using part of the meagre annual purchase grant in buying a picture by the originator of this violent and controversial school of modern painting.127

Funds for the purchase had been provided by Henry J. Heinz II and the H.J. Heinz Company through the American Friends of the Tate. John Hay Whitney used the Pollock purchase to articulate his hope for the continued expansion of the American representation in the Tate collection. ‘I hope, and I am confident, that the first important American painting to be donated by the American Friends of the Tate will inspire other gifts,’ Whitney told the Times, ‘and make possible very soon the establishment, as planned, of a room of representative American works of art.’128 The acquisition of the Pollock was widely reported in the American press as evidence of British acceptance that United States ‘is now taking a commanding lead in creative ideas’.129

The Pollock purchase should not distract from the stylistic variety that characterised the museum’s acquisitions around this time. Allan Emil himself donated the first work to be received through the American Friends committee: the Bacon-esque Untitled 1959 by Bay Area painter Hassel Smith (fig.14), acquired from the artist’s exhibition at London dealership Gimpel Fils. Adeane donated Morris Graves’s Spring with Machine Age Noise No.1 1957 (fig.15) in 1962, securing for the museum a work by an artist that Rothenstein held in high regard. Stephen Greene’s The Return 1950 (fig.16) was donated in 1962 by R. Kirk Askew Jr, of New York dealer Durlacher Brothers. Acquisitions such as these – made before works by many of the more prominent figures named on the museum’s acquisitions lists were purchased – were not merely opportunistic; they should be understood to record Rothenstein’s persistently plural understanding of post-war American art. Even as the British press reported on the Pollock acquisition, Rothenstein outlined his hope that the Heinz gift would stimulate ‘further American bounty’ to ‘go to buy the work of earlier artists like [Albert Pinkham] Ryder or [Winslow] Homer’.130 Such ambitions to strengthen the museum’s holdings of earlier forms of modern art from the United States would remain unrealised, but they capture the breadth of Rothenstein’s art historical ambition.

Following the Pollock purchase, in early 1961 Rothenstein and Adeane were back in the United States again, meeting with the American Friends of the Tate in New York, but also making visits to Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia and Detroit. The Guardian reported of the visit that the Tate Gallery ‘hoped to open two galleries within the next two years to show modern American paintings at the Tate’, noting that the museum now held ‘about twenty’ works from the United States in its collection.131 Rothenstein was keen to emphasise the significance of these visits to America. ‘Sir John said today,’ the Guardian went on to report, ‘that though the centre of gravity of the American Friends was in New York, he and Sir Robert were anxious to visit other cities, no doubt in the knowledge that New York is not America.’132 Upon his return in autumn 1961 Rothenstein reported back to the trustees about his contact with a surprisingly fresh roster of New York artists beyond the emerging canons of abstract painting, including Louise Nevelson and Lee Bontecou.133 Works by both artists entered the collection the following year. Contrary to perceptions of his diminished agency in the last years of his directorship, Rothenstein’s active involvement in such acquisitions confirms his continued commitment to representing a diverse range of recent American art in the Tate collection.

Fig.17

Staircase installation, Tate Gallery, London, 1962, featuring (left to right) Adolph Gottlieb, Green Expanding 1960, Mark Rothko, Black Stripe 1958 and Franz Kline, Light Mechanic 1960

Published in the Sunday Times Magazine, colour supplement, 14 October 1962

Fig.18

Morris Hirshfield

Landscape with Swans 1941

Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee

© Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.19

Richard Lindner

Homage to a Cat 1952

Tate T00538

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Rothenstein continued to take advantage of loans to the Tate collection to supplement the museum’s American holdings. In 1962 major works by Kline, Adolph Gottlieb and Rothko (fig.17) were borrowed from mining magnate Alfred Chester Beatty, and installed on the double-height walls of the museum’s staircase.134 In line with Rothenstein’s taste for American realism, the museum also borrowed two works by self-taught painter Morris Hirschfield, including his Landscape with Swans 1941 (fig.18), from the collection of exiled American screenwriter Donald Ogden Stewart and his wife Ella Winter.135 The presence of such alternate pathways in American art also helps explain the acquisition of works by Greene and Richard Lindner, including the latter’s faux naïf Homage to a Cat 1952 (fig.19). Neither of these artists appear on any of the museum’s lists of priority artists, but in their acquisition we see Rothenstein’s modest effort to assemble for Tate a picture of American modernism that extended beyond the ever-hardening canons of abstract expressionism to embrace its more idiosyncratic margins.

The final priority acquisition lists produced during Rothenstein’s tenure at Tate further confirm such an approach. Amid key figures in abstract expressionism and colour field painting, there were some less likely additions: Richard Diebenkorn and Robert Rauschenberg both appear as top priorities on this list, and artists such as Joseph Cornell, Stuart Davis, Eugene Higgins and Elie Nadelman are included as new acquisitions goals.136 Rothenstein later claimed in his biography that while he recognised the importance of abstract expressionism, he also worried that the movement was a passing fashion:

The New York school of action painters which emerged as a mature movement in the late forties and continued to flourish in the fifties aroused enthusiasm among young painters throughout the Western world, and in the United States pride in the first American art movement to make a forcible impact abroad. When I visited New York in the sixties, though Pollock, de Kooning, Gottlieb, Rothko and several of their colleagues were held in high repute, action painting, as a movement, was as remote, for the younger painters I met, as social realism or even cubism. It was an episode in the long history of art, and episode that gave New York unprecedented prestige as a creative centre, but already half forgotten.137

Swimming against the tide of fashion, but never ignoring its waves, Rothenstein instead delighted in giving ‘due to shy, neglected figures, remote from the mainstream of formative ideas’.138 There was also, I suspect, an ideological imperative behind Rothenstein’s scepticism towards abstract expressionism. This is why, I think, Rothenstein quoted Francis Bacon claiming that New York School painting merely ‘seemed audacious yet could express nothing that could affront their rich patrons.’139 The criticism certainly sounds like Bacon (who was also known to refer to Jackson Pollock as ‘the old lace-maker’140 ) but the perspective also conforms with Rothenstein’s own preference for earlier forms of American modernism whose progressive social commitments were more straightforwardly legible than the mainstreams of post-war abstract painting.

The full gamut of Tate’s American acquisitions in the years of Rothenstein’s tenure recapture an accurately messy vision of modern art – one that had room for John Marin and Richard Lindner, and one within which trustees acquired a work by figurative painter Balthus in the same meeting as a work by Mark Rothko. When a 1964 guide to Tate Gallery names the work of Perlin and Shahn as being among ‘the more realistic kinds of modern American painting, which have continued to develop alongside the abstract art (though somewhat overshadowed by it)’, it is, I suspect, Rothenstein’s voice that we are hearing.141 This was the pluralistic vision of American art enabled by Rothenstein’s interwar experience with earlier modernisms, and by his equivocal attitude towards New York School abstraction.

Rothenstein’s foresight

Rothenstein’s cautiousness towards abstract expressionism, and his enthusiasm for American art of a broader range of styles and from a wider range of places, left an indelible mark on Tate’s collection of American art. ‘While his own tastes are rather conservative, rather than with every new “ism”,’ stated the Daily Telegraph in 1962, ‘he has never been afraid to make sure that every honourable new development of any calibre is represented at the Tate.’142 Breadth had long been Rothenstein’s stated ambition: ‘Every serious movement merits consideration,’ he told an American journalist in early 1940, ‘and it is our policy to acquire for acquisition one or two examples of any such movement that emerges.’143 The result is a uniquely broad picture of modern art at mid-century; a diverse time capsule unscathed by the deaccessioning so prevalent among many American museums.

Also prophetic was Rothenstein’s recognition that the post-war art market was becoming an increasingly global affair. ‘New collectors are entering the field – private collectors with money to invest and new museums in North and South America, Australia and Europe, many with resources vastly greater than Tate’s’, he warned in 1957.144 From the perspective of today’s expanded global art world, and the escalating competitive circuits it has produced, it is worth recalling and emphasising the value of Rothenstein’s more cautious, even conservative, approach to acquisitions. ‘The ultimate assessment of the masters, or of any artist, for that matter, who for one reason or another has been the subject, over the centuries, of intensive study, is the work of time, that is, of the ultimate consensus of the opinion of generations of scholars and connoisseurs,’ Rothenstein wrote in 1970. ‘That their influence may be misused with regrettable or even disastrous consequences few directors of collections of modern art, or few writers concerned with it, need to be reminded.’145