A reluctant member of the loose-knit group of artists who would become known as the New York School, Ad Reinhardt (1913–1967) has proved difficult to place within the shifting landscape of mid-twentieth-century abstract American art. Having been left out of major exhibitions such as The New American Painting, held at the Tate Gallery in London in 1959, Reinhardt was still a relatively unknown figure in Britain at the beginning of the 1960s.1 Yet this would change, and swiftly, in the years leading up to Reinhardt’s untimely death in the summer of 1967, as a string of exhibitions held between 1961 and 1964 introduced his work, albeit framed in a variety of contexts, to London’s art-going public.

Fig.1

Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition 6 American Abstract Painters: Ellsworth Kelly, Alexander Liberman, Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt, Leon Smith, Sidney Wolfson held at Arthur Tooth and Sons Gallery, London 1961

The first of these, 6 American Abstract Painters, held at Arthur Tooth and Sons Gallery, London in 1961 (fig.1), offered a snapshot of different forms of a new geometric abstraction, collectively termed ‘hard-edge’ painting, that had recently emerged as an alternative to the dominance of gestural abstraction in New York and elsewhere since the 1940s. Presenting Reinhardt as an early pioneer of this mode, it conveyed a very different image of the artist to that suggested by 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, held at the Tate Gallery three years later. In this major and well-attended survey exhibition, Reinhardt was placed uncomfortably amid the same milieu from which he had repeatedly attempted to distance himself, namely, that of abstract expressionism. As a potential fix to this, Reinhardt’s first solo exhibition in the UK opened just a few months later at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA). Here eight of his most recent canvases were hung in accordance with the artist’s exacting specifications.

At stake in this sometimes contradictory spate of presentations and accompanying critical receptions would be what Reinhardt identified as ‘the question of heroes and outcasts’ posed by the cultural image of American art abroad – in this case, as it was taking shape in London.2 Carving out a trajectory that went against the grain of this narrative, Reinhardt’s self-appointed, if ambivalent, standing as an outcast would take on an aesthetic-political charge that held consequences for both the context being suggested for his work at the Tate Gallery in particular, and its place within the historical moment more generally.

The antithesis of ‘Action Painting’

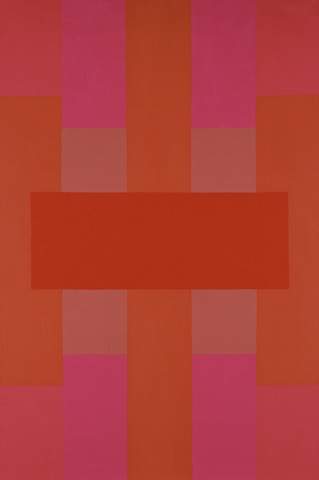

Fig.2

Ad Reinhardt

Abstract Painting No. 5 1962

Tate T01582

© 2019 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Before considering Reinhardt’s first appearance at the Tate Gallery, it is worth pausing over what stands as arguably the most paradigmatic example of his late work in Tate’s collection, Abstract Painting No. 5 (fig.2), which was completed in 1962 and acquired from his widow Rita Reinhardt in 1972. Everything about this work sets it against the credo of ‘American action painting’, as famously outlined by Harold Rosenberg in 1952.3 Its square format repudiates the often gargantuan dimensions deemed necessary within action painting for physically engaging the viewer with the immediacy and import of what the artist had done on the canvas, referred to by Rosenberg as ‘the event’.4 Rather, the scale of the painting relates to the viewer on a one-to-one basis. Although rejecting any humanist sentiment, Reinhardt modelled his 60 x 60 inch (1524 x 1524 mm) canvas on dimensions similar to those of Leonardo da Vinci’s perfectly proportioned Vitruvian Man (‘five feet wide, five feet high, as high as a man, as wide as a man’s outstretched arms’).5 Instead of idealising the body, however, Reinhardt set it into dialogue with the initially solid-looking (and notoriously resistant to reproduction) surface of his paintings. It is only when standing in front of Abstract Painting No. 5 that the viewer can see the varying depths and relative optical densities of the nine squares that make up the pictorial surface, each ever so slightly tinged with a veil of colour that permeates its darkness. Denying the traditional opposition between figure and ground, Reinhardt arranged these squares into rows of three by three, creating a balance or deadlock between verticality and horizontality, with neither allowed to take precedence over the other. Arranging the coloured blocks so that they formed what has been described, somewhat misleadingly, as a ‘Greek cross’,6 Reinhardt was able to pursue his project of making painting ‘purer and emptier’ while calling into question abstract art’s symbolic associations.7

Reinhardt made over one hundred such works, each apparently identical but inevitably suffused with differences due to their handmade quality. The characteristically matte finish of their surfaces was achieved through a long and painstaking process that involved steeping black paint, mixed with tiny amounts of red, green and blue pigment, in turpentine, which was then left to stand in jars kept on the windowsill of the studio for months at a time. The resultant mixture, drained of the heavy residue that lends oil paint its gloss and weight, was layered onto the canvas in sections with a wide brush to create the nine velvety squares of subtly variegated hue that constitute each of Reinhardt’s ‘last’ paintings, or, as the artist himself described them, ‘the last painting which anyone can make’.8 Widely misconstrued as a statement declaring the end of painting, Reinhardt’s emphasis on the egalitarian potential of his method (however unlikely in reality) suggested instead that his paintings posited a future premised on art’s demystification. As well as didactic in intent – Reinhardt was a teacher of both fine art and art history – the ‘last’ paintings suggested that one had to make one’s own rules by which to live, work and conduct oneself in spite of the common consensus, particularly when the latter proved harmful to one’s conscience.

Fig.3

Alexander Liberman

Continuous on Red 1960

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fig.4

Ad Reinhardt

Red Abstract 1952

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

© 2019 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Yale University Art Gallery

That this point would be repeatedly missed, or else ridiculed, during Reinhardt’s lifetime is evidenced by the many nicknames the artist accrued in Manhattan, such as ‘The Black Monk of New York’ and ‘Mr. Pure’.9 Across the Atlantic, however, he was also gaining recognition as a forerunner of hard-edge abstraction, a term originating on the West Coast of America that was imported to the UK by critic and curator Lawrence Alloway in 1960.10 The following year, in 1961, a small selection of Reinhardt’s earlier paintings was included in Alloway’s aforementioned 6 American Abstract Painters. Featuring a roster of other artists also represented by Betty Parsons, who was Reinhardt’s chief dealer in New York between 1946 and 1963, the show was accompanied by a catalogue in which Alloway attempted to identify the aspects unifying the works of an otherwise disparate group. Ranging from Agnes Martin’s ‘unhasty but unworried’ rows of discrete shapes on monochrome grounds, to the ‘punctilious finish’ of Alexander Liberman’s large paintings, such as the recently completed Continuous on Red 1960 (fig.3), the British curator detected within each artist’s work a use of ‘edges’ that are ‘hard and clear enough to permit both negative and positive readings’.11 Although equally New York-centric, this would be quite a different group to that with which Reinhardt was often shown, a point Alloway implicitly addressed when suggesting that all the featured paintings, while at times jarringly different in their inception and perceptual effects, represented ‘the antithesis of “Action Painting”’. Devoting a significant central paragraph to Reinhardt, Alloway held up his Red Abstract of 1952 (fig.4) as a prototype of the kind of ‘optical drama [created] on the basis of a monotonous format’ that exemplified this mode of painting.12

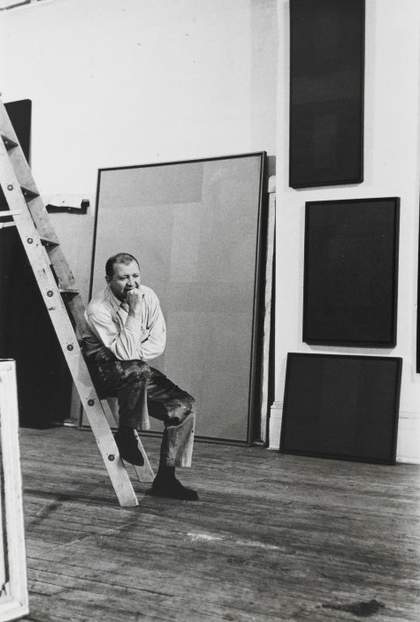

Fig.5

Fred W. McDarrah

Ad Reinhardt, New York, 4/1/1961 1961

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

© Estate of Fred W. McDarrah

While it might be tempting to dismiss Alloway’s use of the ‘hard-edge’ label as a fantasy projection, willed out of (and adapted from) a need for a critical vocabulary particular enough to describe an especially reticent form of abstraction, there is some evidence that it took root beyond the London art scene (where, as art historian Nigel Whiteley has shown, it was embraced to a considerable degree).13 In the same year as the exhibition 6 American Abstract Painters, Fred McDarrah published The Artist’s World in Pictures, a book chronicling the contemporary situation in New York, illustrated with photographs taken by the author. In the penultimate section, entitled ‘New Images and the Hard Edge’, is a portrait of Reinhardt in his studio, holding a pose of contemplation while perched on a ladder, with one large canvas and three smaller and darker paintings displayed on the wall behind him (fig.5). Although not referred to directly in the short accompanying text, Reinhardt appears as a representative of the hard-edge ‘trend’, characterised by its adherence to the ‘purist’ principles of ‘clean, hard edges and pure, primary colors’.14 This was in contrast to the ‘concern for symbols’ preoccupying ‘New Image’ painters – another term for those artists associated with gestural painting and its surrealist underpinnings which Reinhardt steadfastly rejected, after having dabbled in its techniques (most notably the ‘all-over’ surface) during the 1940s.15 Borrowed from Los Angeles, established in London, and imported back to New York, the term ‘hard-edge’ could be said to have been a transatlantic phenomenon for which Reinhardt emerged as an unlikely luminary.

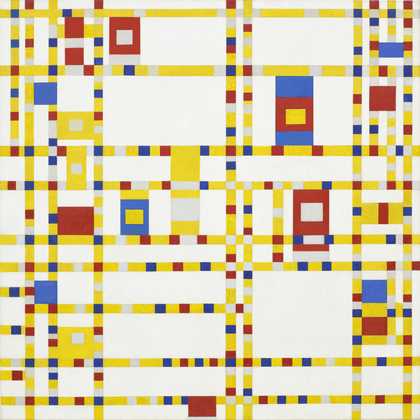

Fig.6

Piet Mondrian

Broadway Boogie Woogie 1942–3

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Neat as this theory may sound, Reinhardt’s role proved far from straightforward. Although upholding art’s purity as the ultimate standard of any artist’s work and the one saving grace that differentiated it from being merely a form of commodity production, Reinhardt had a complicated relationship with pure abstraction as an artistic tradition. Claiming that Piet Mondrian had not gone far enough before lapsing into his late ‘boogie-woogie’ phase in the 1940s (see, for example, Broadway Boogie Woogie; fig.6), which seemed to celebrate the chaotic rhythms of urban life that the Dutch artist’s previous output had – in his view – done so much to quieten,16 Reinhardt also remained suspicious of the symbolic utopianism driving Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square of 1915 (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) and related works.17 Identifying both artists’ contributions as tipping points in art history, he consequently sought to outdo (and, in some cases, cancel out) their terms.18 As Reinhardt put it in 1963, shortly after the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired one of his ‘last’ paintings,19 his work stood:

As the most extreme, ultimate, climactic reaction to, and negation of, the (cubist, Mondrian, Malevich, Albers, Diller) tradition of abstract art, and previous paintings of horizontal bands, vertical stripes, blobs, scumblings, bravura, brushwork, impressions, impastos, sensations, impulses, pleasures, pains, ideas, imaginings, imagings, imaginations, visions, shapes, colors, composings, representings, mixtures, corruptions, exploitations, combinings, vulgarizations, popularizations, integrations, accidents, actions, texturings, spontaneities, ready-mades, stylizations, mannerisms, irrationalities, unawarenesses, extra-and-unesthetic qualities, meanings, forms of any traditions of pure, or impure, abstract-art traditions, my own and everyone else’s.20

Nevertheless, Reinhardt’s subtleties and contradictions would be lost on many commentators. In his 1959 article, ‘What Happened to Geometry?’, the American critic and painter Sidney Tillim explicitly singled out Reinhardt as a self-appointed successor of this purist past, whose work exemplified purism’s demise into self-affirmation.21 Describing Reinhardt’s as an aggressively objective stance, Tillim deduced that its political stakes had become cloaked by a stylistic moniker that demonstrated the very ‘gulf between artist and public’ that pure geometric art had previously attempted to bridge. Even supporters of Reinhardt tended to agree. In his introduction to McDarrah’s book, Thomas B. Hess (then editor of ARTnews, who would publish a book on Reinhardt’s practice as a satirical cartoonist in 1975) emphasised that self-containment of this kind had no place within the ‘anti-chauvinistic, international outlook’ of ‘New York art’ during the 1950s.22 Offering Reinhardt up as a brooding hermit, McDarrah’s portrait problematically compounded such views.

If taken as a shrewd bit of self-staging, however, the portrait’s posed fiction can be seen as one way in which Reinhardt did not so much contradict Rosenberg as anticipate the latter’s realisation that the ‘triumph’ of abstract expressionism had, by this time, come to obscure its fundamental rootedness in the sanctity of the viewing encounter. Although Reinhardt would later be shown in the act of painting in a set of widely circulated images taken by John Loengard in around 1966, his stance in McDarrah’s image is defiantly detached. According to Rosenberg, the reception of post-war American painting had ‘de-defined’ its parameters – that is, had replaced the specificities of the art object as a world in itself with its presentation as part of a larger, conceptual brand – and shifted the artist’s identity from a maker of things to a player in the ‘World Game’ of self-publicity.23

While perhaps smacking of nostalgia, Rosenberg’s lament came after a decade during which what had seemed to the critic to be the singular achievements of modern American art were contextualised and recontextualised over and over again to the point of exhaustion. Although intolerable for Rosenberg, this process of institutionalisation also rendered the place of its less assimilable or willing representatives continually up for negotiation. Enacting a kind of boomerang effect that ran counter to its denoted rigidity, the ‘hard-edge’ presented itself as a potential agent of change that transformed as it migrated across the Atlantic, detaching itself from the historical specificity of locale as it went. Perhaps this is why Reinhardt did not refuse the term outright, as he had done with so many others. While disastrous for Rosenberg in that it threatened to neutralise the sting of action painting through over-exposure, the explosion of ‘global’ surveys, international exhibitions and career retrospectives punctuating the 1960s presented several chances for Reinhardt to take control of his own historical image. (This was a hard-won privilege, born of neglect, and one that had eluded many of Reinhardt’s more lauded contemporaries.) Following the introduction provided by 6 American Abstract Painters, two further, parallel exhibitions in London offered the most immediate opportunity to do so.

An abundance of Reinhardts

Fig.7

Photograph of the private view of 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, 22 April – 28 June 1964, Tate Gallery, London

Tate Archive Photographic Collection TGA PHOTO/9

© Tate

Fig.8

Ad Reinhardt

Untitled (Composition #104) 1954–60

Oil on canvas

2813 x 1086 x 64mm

Brooklyn Museum, New York

© Estate of Ad Reinhardt

Having been left out of the Tate Gallery’s 1959 exhibition The New American Painting, Reinhardt finally appeared in another exhibition held at the gallery five years later but perhaps not to his best advantage. Sponsored by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and jointly curated by Lawrence Gowing, Alan Bowness and Philip James, with the assistance of Paddy Bowling, the survey show 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade included over 350 exhibits. Specially designed by British architects Alison and Peter Smithson to accommodate and complement the massive array of artworks brought together from across Europe and North America, the exhibition’s inventive set-up of makeshift partitions affixed with individual spotlights divided opinion (fig.7). Criticised by some for turning the Tate Gallery’s large and airy spaces into ‘a series of bays like fall-out shelters’, the Smithsons’ design was lauded by others for bringing ‘the booming halls of the Tate ... down to human scale by mazes of screens and lights’.24 Yet this layout ultimately seemed to emphasise the partisanship demonstrated by members of the curatorial committee when selecting which works best represented this seminal period, years in which ‘a sense of living in a pre-war or post-war age’ had, they claimed, finally passed.25 Shown opposite five colourful works by Willem de Kooning, three of Reinhardt’s slender, elongated and characteristically dark canvases of the mid-1950s (see, for example, Untitled (Composition #104) 1954–60; fig.8) hung on the left-hand side as visitors passed through a network of ‘narrow clinical corridor’-like partitions.26

Fig.9

Cover of the exhibition catalogue for 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, held at the Tate Gallery, London, 22 April – 28 June 1964

Marred by a ‘harrowing ... “hang”’,27 an error-filled catalogue that needed reprinting (fig.9), and damage to several artworks, the show prompted some fundamental questions over what shape art’s recent past and immediate present was taking, and who exactly was doing the shaping. While presenting itself as both an overview and a review of ‘the kinds of painting and sculpture that have seemed to increasing numbers of people in many countries to be particularly characteristic of these years [1954–64]’,28 the exhibition was widely deemed more indicative of what curator Bryan Robertson termed the ‘absurd race’ for international recognition dogging British institutions, which were trying to prove London’s relevance as an ‘art capital’ to rival New York and Paris.29 Although the display began with works by Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, many critics noted that there seemed to be an unfair ‘bias’ towards recent work made by young American – and to a certain extent British – painters, with little room left for that of their elder – and French – counterparts.30

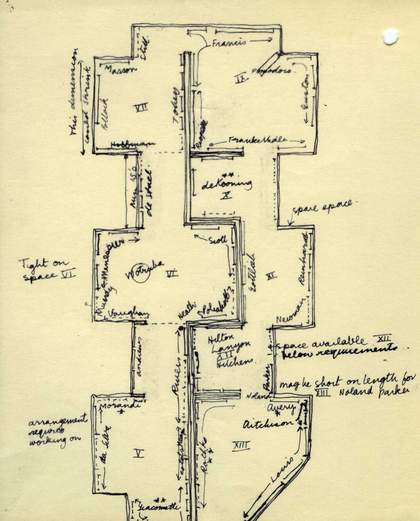

Fig.10

Alison and Peter Smithson

Floorplan for the exhibition 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade at the Tate Gallery, London

Tate Archive, Exhibition File TG 92/181/2

As important as who was represented in the show, however, was how representative their work was seen to be. At least five central rooms were dedicated to abstract expressionism, more than any other ‘kind of painting and sculpture’ on display.31 As seen in the Smithsons’ initial floorplan (fig.10), Reinhardt’s paintings were originally intended to appear in room 11 alongside a small number of canvases by Barnett Newman and opposite three by Adolph Gottlieb. The reason for the curators’ change of heart is unknown but this repositioning did little to activate a larger dialogue about the variety of positions offered within, and against, gestural abstraction. Instead, it threw into question the significance of Reinhardt’s work specifically. One letter of complaint sent to the curators stated bluntly that some visitors struggled to see the ‘meaning’ of, or artistic merit in, ‘the three all-black door panels’ that faced de Kooning’s large paintings.32 For the critic David Sylvester, more than exposing the insensitivities of the public’s ‘savage breast’ (and, moreover, the cultural elite’s disdain for it),33 such reaction was the result of the exhibition’s overwhelming layout. Although a ‘rich and exhilarating’ selection, according to Sylvester the show was ‘laid out in such a way that encourages us to see works of art as signals of attitudes rather than as works to be contemplated.’34 Propelling the viewer from one work to the next, the innovative exhibition design could only result in a series of fleeting encounters which were barely sufficient for fostering the kinds of experiences deemed fundamental to much of the work on display and, thus, for recognising each distinct contribution.35

Fig.11

Ad Reinhardt

Installation view of the exhibition Ad Reinhardt, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1964

© 2019 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.12

Ad Reinhardt

Installation view of the exhibition Ad Reinhardt, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1964

© 2019 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.13

Ad Reinhardt

Installation view of the exhibition Ad Reinhardt, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1964

© 2019 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.14

Ad Reinhardt

Installation view of the exhibition Ad Reinhardt, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1964

© 2019 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It is telling that Sylvester’s assessment of these shortcomings would be conveyed in his review of Reinhardt’s concurrent solo exhibition in London, which opened at the ICA, then still located on Dover Street, just a few weeks after Painting and Sculpture of a Decade. Even more telling, perhaps, would be Paddy Bowling’s suggestion that Reinhardt’s show offered something of a fix to his presentation at the Tate Gallery,36 unwittingly confirming that, as Sylvester put it: ‘Opposing the easy-going, free-for-all attitude of most recent abstract art, which acts as a stimulant to the spectator’s fantasy, Reinhardt presents the spectator with an artefact from which he will get nothing unless he is willing to look hard at something outside of himself.’37 Proudly declared as Reinhardt’s British première, the ICA exhibition provided the first opportunity to see his square canvases en masse in Europe, outside of France (Reinhardt received a solo exhibition at Iris Clert’s gallery in Paris the previous June).38 Lining the walls of the exhibition space, wedged between jutting pillars, and hung at different heights to accommodate the room’s dimensions (as seen in a set of photographs taken by the artist; figs.11–14), Reinhardt’s display of a handful of the ‘last’ paintings left no room for misinterpretation. With the paintings roped off, as critic Guy Brett noted, by ‘lengths of string, like altar rails’ to protect their vulnerable surfaces,39 the onus lay on the viewer to exert the kind of effort described by Sylvester when encountering the works. Moreover, critic Robert Melville’s observation that one had to stand at an oblique angle in order to see the paintings’ inner squares suggests that this involved a certain amount of physical, as well as perceptual, effort.40 While perhaps a less than perfect setting, ‘the air of a sanctuary’ achieved by Reinhardt at the ICA offered apparent respite from the hectic (and largely antagonistic) atmosphere surrounding his work a few miles away at the Tate Gallery’s Painting and Sculpture of a Decade.41

Yet the increased control afforded by a one-man exhibition came at a cost. In contrast to the £35,000 made available to the selection committee of the Tate show in order to secure loans,42 Dorothy Morland, then director of the ICA, regretfully relied upon Reinhardt’s own resources to fund his exhibition.43 As Reinhardt half-jested to Betty Parsons: ‘I’m paying transportation for my paintings, my body, my soul myself’.44 To garner free publicity, Morland invited Reinhardt to give a lecture among his paintings, as well as arranging an interview with Granada television (which, to my knowledge, was never aired).45 Having heard about the exhibition from Morland, Francis S. Mason, the Cultural Affairs Officer of the United States Information Service, offered to advertise the exhibition by hanging one of the paintings in the American Embassy, should there be ‘an abundance of Reinhardts’ available to lend.46 (It is unclear whether Mason‘s offer was accepted, but Morland replied promising to request another painting from Reinhardt for this purpose.47 )

To what extent might Reinhardt’s well-publicised ICA exhibition be seen to have redressed his representation at the Tate Gallery? Reinhardt had begun planning his solo show with Morland around the same time that he was approached by Lawrence Gowing for inclusion in Painting and Sculpture of a Decade.48 Although Reinhardt had previously expressed concern over showing old work while trying to present his new paintings, it seems the potential gains of doing so, particularly to a new audience, in this case outweighed the pitfalls.49 Moreover, it presented the chance to play an active role in spearheading his belated reinstatement into a larger and ongoing story. In the lecture delivered among his paintings at the ICA, Reinhardt suggested that Painting and Sculpture of a Decade ‘raised the question of a climate favourable to art today. And the question of who was inside and who was outside, the question of heroes and outcasts, and I guess I’ve been outside, I’ve been an outcast or at least not a howling success.’50 Although critics such as Anita Brookner saw Reinhardt’s (self-declared) outsider position as reason enough to dismiss his work, for Alloway, Sylvester and Brett it stood as a form of opposition to the foreclosure of a history that was evidently still in the making.

If the Tate Gallery appeared to some as a ‘Storage Room for VIPs (Very Important Paintings)’, to echo the words of Reinhardt’s Parisian dealer at the time, Iris Clert,51 then Reinhardt’s modest presentation at the ICA conversely functioned as a safe-house for paintings whose perceived ‘meaning’, or lack thereof, crucially depended upon their setting. In this way, Reinhardt’s solo exhibition seemed to confirm art theorist André Malraux’s claim, made in The Voices of Silence: Man and His Art (translated into English in 1953), that artworks are fundamentally changed by the contexts in which they appear – a claim Reinhardt cited often.52 It also served to test the assumption, held by both the Tate Gallery exhibition’s curators and some of their detractors, that abstract geometric painting was now little more than ‘one failed strain of the school of Paris’, which was being further degraded by its American successors either through ‘active plagiarism’ or thinly veiled pastiche.53

Amid this (rather prescient) nexus of unease over the presentation, representation and reception of contemporary American art, it is perhaps unsurprising that Reinhardt dismissed the vertical format of his paintings showcased at the Tate Gallery (and in paintings such as Untitled (Composition #104); fig.8) as ‘too decorative a shape’ in the Q&A session following his ICA lecture.54 Likened to Chinese scrolls and Japanese wall-hangings, their narrow rectangular format seemed to accommodate these paintings too readily to the needs of the eye, whether via the realm of what Hess termed ‘that dreaded word – beauty’ in an earlier review of Reinhardt’s mid-century works,55 or else to the humdrum world of domestic objects, as their aforementioned misinterpretation as ‘door panels’ suggests. Reinhardt himself took the belated institutional recognition of his work as a sign of its resistance to institutionalisation, reflecting with characteristic drollery: ‘someone said that the Museum of Modern Art had not only scraped the barrel but they had bought everything in sight, and then they were starting on me.’56

Almost famous

As a stranger in a strange land, Reinhardt could play the role of adversary in a way that drew out the subversive humour underlying the earnestness of his stance. The ICA lecture is a case in point. Nestled in his discussion of the Tate Gallery’s exhibition was a reference to a show of Franz Kline’s work concurrently on display at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. Reinhardt objected to the language used in the Kline catalogue essay, written by Frank O’Hara, in which his fellow artist was presented as ‘the Action Painter par excellence’.57 As Reinhardt said in an interview at the time:

there are much better targets [for criticism] than Kline in American painting ... But the idea of Abstract art, loaded with a sense of human experience, sounds not right. The idea of predicament or imbalance or despair or involvement, tragic sensibility, the idea of the unconscious there and the idea of action painting and humane painting, feeling paint … The idea of private compulsion exciting public appetite … there’s been a little too much expressionist wearing art and sweat and tears on sleeves by artists … [and] artists standing around with their hats in their hands.58

It was everything his own art refused to engage with. Throughout his talk Reinhardt made a habit of quoting others and withholding further comment, a key tactic used in his writings. The idea behind this was that others needed no help in explaining themselves or showing themselves up. Take, for example, this snippet: ‘I’ll only mention de Kooning’s expression, in an interview with [Sylvester] in which he said “I’m not a country dumpling”. I think he meant bumpkin, but I don’t know why he said that.’59 A little later he added, in relation to Melville’s review of Painting and Sculpture of a Decade: ‘the real content of painting [is] not just the visible motif, but the whole situation, and I think Melville said something about rat race, and I won’t say anything about that.’60

Zooming out from the individual to the conditions of the wider field which one is forced to navigate, Reinhardt suggested that painting itself could demonstrate this dynamic by forcing one to step away from the action, as it were, in order to actually see it. Perhaps, conversely, we could think of Reinhardt as an inaction painter, insofar as he wanted his paintings to suggest refusal, if not quite withdrawal, as an alternative to cooption. Yet Reinhardt seemed to protest too much for some. Rosenberg never forgave him for casting himself out of the gang. Smacking of sour grapes, Reinhardt’s strategic tirades appeared to the critic as the regrettable upshot of an ‘unremitting one-against-all polemics’ which ‘damaged the solidarity’ of a milieu that had, in reality, only on a single, fleeting occasion formed a united front.61 Rosenberg was not alone in this view. So offended was Newman by a comment made about him in one of Reinhardt’s ‘Art-as-Art’ pieces that he proceeded to sue (to no avail).62 Even Hess, who numbered among Reinhardt’s favourite interlocutors, pointed out that he had never quite been in step with his own generation.63 Reinhardt’s unacceptability was widely accepted, even if his art would take time to be seen as acceptable.

As critic Nancy Flagg put it in an account of her old acquaintance, by the summer of 1965 ‘Reinhardt was almost famous, not so much for the brilliance of all his past paintings as for the obscurity of his recent black-on-black ones’.64 Come the next year, however, he had fallen into ‘shameless fame’. Although Reinhardt was far from obscure in America, Flagg’s knowing comment sums up the precipice that the situation in London must have represented for the artist upon his return home. He was, after all, preparing for the most significant show of his career, a large retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York. Here his ‘last’ paintings would be shown much as they had been at the ICA, but on a larger scale and in more familiar (and favourable) surroundings. Even on the verge of this milestone, Reinhardt adopted an ‘if you can’t join them, beat them’ attitude. For the show’s catalogue, he wrote a timeline of his career. Knowingly mocking this convention as used by contemporaries such as Robert Motherwell, Reinhardt interspersed his own biographical information with historical events and seemingly arbitrary occurrences. Under the year 1964 appears one such occurrence: ‘Ten paintings in London get marked up’.65 Despite his best efforts to keep it at bay, the world found a way into Reinhardt’s paintings, no matter where in the world they were. Paradoxically, this insistence on standing apart also marked them as part of a moment in which the borders of art were irrevocably shifting; a moment in which being ‘almost famous’, or ‘at least not a howling success’, offered the distance needed to see the bigger picture and to act accordingly.