Fig.1

Sir John Rothenstein

Tate Archive

In January 1956, key museum staff at Tate made their first steps towards the acquisition of contemporary American art in earnest. Ronald Alley, then Keeper of the Modern Collection, wrote to Tate Gallery Director John Rothenstein (fig.1) in New York to suggest the names of American artists that the museum might acquire.1 Alley listed ten artists: Ben Shahn, Arshile Gorky, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Mark Tobey, John Marin, Lyonel Feininger and Jackson Pollock. Alley further specified of Hartley and Gorky that ‘late’ works would be preferable, that an attractive de Kooning might be an ‘abstract or figure’ painting, and that Tobey would be best represented by an ‘abstract’. Alley also admitted, however, that some of these artists might already be ‘too expensive’ for the museum’s budget.2

There are several aspects of the letter worth pointing out. The first is that Rothenstein, despite his experiences and enthusiasms as detailed in my essay ‘American Art under John Rothenstein’, relied on his staff to suggest these names. Alley would continue to play a crucial role in the museum’s collecting of American art in the following decades. Secondly, as with many of the museum’s priority lists from this period, the focus here seems to be less a holistic vision of a national art than a list of its leading contemporary figures. For Alley, this included contemporary abstract painters like Pollock and Kline, and in the case of Gorky and Tobey, he was careful to emphasise that it was only their later or abstract work that was of interest. But despite the focus on well-known figures, Alley does not exclude more diverse strands of American painting. He includes artists better known for their contribution to pre-war modernisms, such as Marin, Hartley and Feininger; leading realists like Hopper and Shahn also appear, whose inclusion in the list reflects the contemporary prominence of the realist style in London. Just as notable are those artists who are missing – there is no mention of Georgia O’Keefe or Jacob Lawrence, for example, artists who remain absent from Tate’s collection.

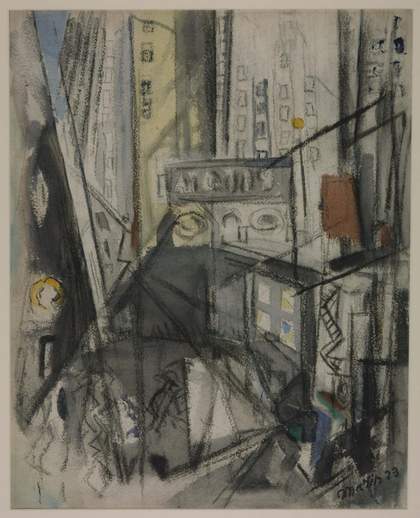

Fig.2

John Marin

Downtown, New York 1923

Tate T00080

© reserved

The chief source for Alley’s foundational list was the presence of these artists in Modern Art in the United States, the influential touring exhibition then on display at the Tate Gallery and explored in an essay here by Frank Spicer. But where the exhibition which so informed his thinking encompassed printmaking and sculpture, and included work by women, Alley limited his acquisition response to paintings by male artists. It is interesting to note when works by the artists Alley named were then acquired, if at all. Somewhat surprisingly, the first was John Marin’s Downtown, New York 1923 (fig.2), which Rothenstein brought back to London with him; it would be another decade or so before Tate acquired works by de Kooning and Gorky. Many of the artists continue to be represented in the collection by a single work (Marin, Shahn, Kline), while several have never entered the collection (Hopper, Hartley, Feininger). Consisting simply of the names of artists rather than specific artworks, Alley’s list is the first of many imaginary collections that exist in the records of the museum, fantasy collections always inevitably subject to the messier realities of acquisitions processes, market forces and shifting tastes. As the museum continues to acquire works by American artists past and present, this is a history that continues to be written.

Beyond canons

If Alley’s list assembles many of the most prominent names in American art – bringing together the less internationally recognised figures of pre-war American modernism and the canonical figures of post-war painting – the realities of Tate’s collection are rather more complex. It is important to remember that Tate had acquired a number of works by twentieth-century American artists before the mid-1950s. Many of these were gifts to the museum, including works by Charles Burchfield, Maurice Sterne and Bernard Perlin. The history of Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948 is comprehensively detailed here in an In Focus project led by Aaron Rosen. Other early acquisitions were more opportunistic – Theodore Roszak’s The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952 was shown at the Tate Gallery as the artist’s entry to the influential international sculpture competition on this theme, and is explored in my own In Focus project that takes advantage of the museum’s more recent acquisition of drawings related to the sculpture.

Fig.3

Sue Fuller

String Composition 128 1964

Tate T00757

© reserved

Refiguring American Art has sought, where possible, to expand its view to artists on the fringes of the American canon. Unlike in many American museums, works that enter the Tate collection rarely leave it. In the case of a work such as String Composition 128 1964 by Sue Fuller (fig.3), whose delicate string constructions have been quietly deaccessioned by several of the American museums that purchased them in the mid-1960s, the opportunity to study this work as an In Focus project is not just a matter of revisionist rediscovery; it provides a context to address the shifting tastes that have so forcefully ensured Fuller’s persistent marginality, even given the serious efforts to address achievements of women artists at Tate and elsewhere. At a different stage of these shifting assessments, the museum’s acquisition of Norman Lewis’s Cathedral 1950 in 2015 participates in the critical and commercial re-evaluation of this artist’s practice, which Andrianna Campbell engages with directly in her In Focus project on this painting. There are many other Tate acquisitions whose makers merit further attention, and it is hoped that the new summary texts commissioned as part of this project on works by artists such as James Brooks, Stephen Greene and Frank Roth may spur their further scholarly consideration.

To directly address questions of canons and canon formation, the second scholarly event of Refiguring American Art – organised with Tate curators Isobel Whitelegg, Sonia Dyer and Stephanie Straine in 2015 – brought together seven papers under the title ‘Blind Spots: Revisiting the American Canon’. In seeking to address the revisions of the post-war canon, this event especially addressed social and performative practices beyond the mainstreams of museum collecting. Such a subject necessarily confronted the agents of such structures, with the museum chief among them. The keynote for this symposium by art historian Darby English exemplified the rich possibilities for an art history that embraces forms of material culture conventionally excluded from the collecting remit of the art museum.

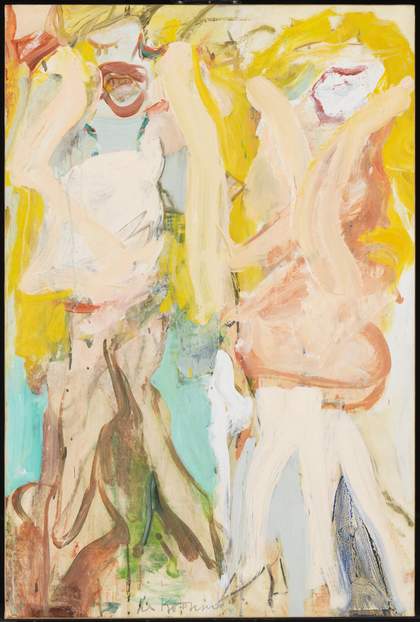

Fig.4

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing II 1966

Tate T01178

© Willem de Kooning Revocable Trust/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Perhaps the forensic nature of the In Focus format engenders a sympathetic understanding of the many kinds of marginality experienced by artists; even the seemingly major figures of New York School painting have provoked such questions. Hans Hofmann’s Pompeii 1959 provides a prime example of the work of an artist who is, as Emily Warner’s In Focus project describes, ‘at once central and peripheral, well-studied and undervalued’.3 Franz Kline’s Meryon 1960–2 and Willem de Kooning’s Women Singing II 1966 (fig.4) might exemplify the trademarks for which these figures are best known, but, as discussed in In Focus projects by AnnMarie Perl and Valerie Hellstein, they each came from a later period than the works that made the artists famous. There is certainly an aspect of belatedness to many of Tate’s acquisitions of abstract expressionist works, following cues provided by the touring exhibitions it hosted. The gallery, however, was hampered as much by limited available stock as by meagre budgets.

Despite John Rothenstein’s own personal interest in American art before the Second World War, and his acquisition of John Marin’s Downtown, New York 1923 in 1956, Tate’s collection is not well placed to explore the continuities between pre- and post-war modernism, especially since these connections are too often obscured by the use of the war as a fundamental break in art historical contexts. As Caroline Riley’s essay about the 1940s collaboration between the Tate and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. demonstrates, the frameworks for the canonisation of American art were still up for grabs in the decade after the war. Furthermore, the ‘post-war’ designation fails to allow for continuities before and after the war, or indeed deal substantively with the impact of the war itself. The ‘post-war’ label also has a tendency to obscure the persistence of armed conflict throughout the experience of America in the 1950s through to the 1970s. The Cold War held a central position in American thinking, as did concurrent processes of decolonisation. Both were prominently reflected in the artistic idioms employed by artists of this period, as the Second World War had been by those practicing in the 1940s. The impact of these ideological contests leaves an unmistakable impact on the art and artists studied in this project.

Traversing categories

In their account of the directorship of Norman Reid, Pam Meecham and Julie Sheldon emphasise that the ‘need to classify and organise’ the museum’s collection of art from the United States was a driving concern throughout the 1960s and 1970s, even as American practice itself was appearing to splinter into a pluralism that evaded such goals.4 The result was a complex museological programme that, on the one hand, pursued the inherited model of modernism from impressionism to abstract expressionism as embodied in particular art objects and, on the other, was increasingly oriented towards a set of avant-garde happenings or interventions, some of which were intended to question the logic and authority of the public art gallery as a temple of value.5 As Reid fostered an institutional context in which these divergent narratives could coexist, Tate’s acquisition and presentation of American art revealed an increasingly eclectic vision of its trajectories.

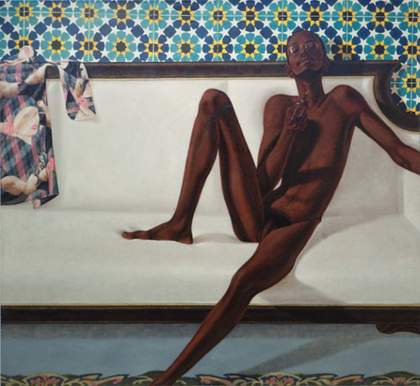

Fig.5

Barkley Hendricks

Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974

Tate T15093

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Just as the museum began to destabilise the categorisation of American art, so too did artists themselves. Several of the In Focus projects in Refiguring American Art address artistic ambivalences towards the categorisation of art movements, and the efforts of artists to extend their limits. Liliana Porter’s Wrinkle 1968, as Sophie Halart puts it, represents ‘a subtle, yet stubborn, resistance to attempts to place an identification tag on it’.6 Barkley Hendricks’s Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974 (fig.5) engages a deliberate shuttling between figurative conventions and flat surface pattern and, as Anna Arabindan-Kesson describes, ‘negotiates some of the complex intersections between abstraction and representation that permeated contemporaneous debates’ across abstraction, pop and photorealism.7 In Hendricks’s case, the expectations for black artists to represent their race added further complexity to these intersections.

Nicholas Martin’s contribution to the In Focus project on Larry Rivers’ Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961 explores how this ostensibly proto-pop painting might be understood within the formal idiom of gestural abstraction and, for that matter, the linguistic turn more ordinarily associated with conceptual practices. Rivers’s picture was included in the 2016 Tate Liverpool display Reconfiguring American Abstraction, which sought to emphasise the uncertain boundaries between abstract and figurative tendencies in mid-century American art. Also in the display were works by Andy Warhol, Harry Callahan and John Chamberlain that equally registered these overlapping formal idioms between pop and abstract expressionism.

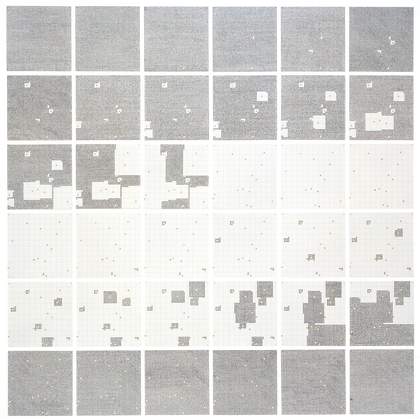

Fig.6

Jennifer Bartlett

Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972

Tate T10037

© Jennifer Bartlett

Sculpture is a particular territory where these boundaries have been contested. ‘[James] Rosenquist’s association with pop art has often prevented consideration of his three-dimensional and environmental work’, explains Thomas Morgan-Evans in his contribution to the In Focus project on Rosenquist’s Silo 1963–4. Morgan-Evans seeks instead to ‘complicate the narratives within art history that have tended to dichotomise pop, associated with two dimensions, and minimalism, associated with three’.8 Emphasising their capacity to cut across such boundaries, Kirsten Swenson argues that the laboriously handmade industrial modules of Jennifer Bartlett’s Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972 (fig.6) – supports for painting but also sculptural objects – at once ‘summarise, contest and expand … dominant artistic strategies’ of the period.9 As John R. Blakinger demonstrates in his project on Dennis Oppenheim’s Salt Flat 1968, the artist’s conceptualism directly addresses the critical discourses of minimal sculpture and of modernist monochrome painting. The resolutely material interests of Oppenheim and other conceptual artists included in the project help complicate the discourses of dematerialisation that have dominated scholarship in this field.

While the lack of works of American art from before the Second World War in the collection means that Tate is largely unable to address the relationships between post-war abstraction and its pre-war precursors in its displays, these connections are repeatedly observed across Refiguring American Art. Aaron Rosen rightly understands Bernard Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948 to open ‘a rewarding window upon a period of fruitful flux in American art’.10 As Erika Doss’s contribution to the same In Focus project emphasises, the traversal of artistic categories also engages other kinds of exclusions. In Perlin’s case, she explains, it was not simply the fact that he was working in a seemingly outmoded realist style that demanded he engage with questions of marginality; his Jewish and queer identities ‘heightened his particular sensitivity to issues of power and vulnerability’.11 Andrianna Campbell’s attention to the connections between Norman Lewis and Lyonel Feininger, or my own exploration of the links between Kenneth Noland’s Gift 1961–2 and the kinds of colour effects pursued by artists like Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe, seek to bridge the artificial divide of the post-war category. The series of workshops presented as part of the project has been a further context for such transhistorical relations to be developed, and papers by Margaretta Lovell, Katherine Manthorne, Angela Miller, Melody Barnett Deusner, Marina Moskowitz, Caitlin Beach and others have allowed Refiguring American Art to register periods and forms of American art absent from Tate’s collection.

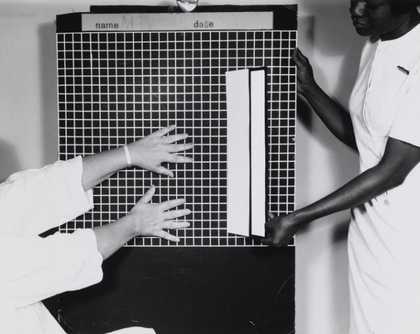

Fig.7

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from the photobook Evidence 1977

Tate P14485

© Larry Sultan/Mike Mandel

To seek other, further signs of flux and hybridity in American art, several projects here excavate the presence of surrealist strategies in works not usually understood in this way. As Allen Fischer describes, the contribution of Fluxus poet Emmett Williams to Porter’s Wrinkle 1968 similarly engages the surrealist enthusiasm for chance operations and punning humour. Although less specifically addressed to surrealist prototypes, John R. Blakinger’s description of the shift from the scientific logic of early systems-based works such as Oppenheim’s Salt Flat 1968 towards mysticism and magic hinges on the borders between rationality and irrationality. By contrast, in his project on Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s Untitled (Evidence) 1977 (fig.7), Andrew Witt counters conventional readings of the work as an irrational archive by emphasising instead the poetic effects of its socio-cultural references and careful sequencing. Such perspectives were also advanced through the workshop ‘Special Relationships: American Artists and their Collaborators’, co-organised with Matthew Holman, which brought to the fore the surrealist-inflected, poetic and often queer artistic milieu that made such an important contribution to the intersecting fields of American arts and letters in the 1950s and 1960s.

Ronald Alley’s 1956 list conforms to the mainstream of 1950s American art in its exclusion of explicitly surrealist practice, but Tate’s collecting activities have long attended to the surrealist aspects of American art. Acquisitions of works by Dorothea Tanning, Man Ray and William N. Copley in the 1950s confirm the early attention paid to surrealism in America. As with the donation of Perlin’s Orthodox Boys – which reflected the commitment of its donor Lincoln Kirstein to the practices it exemplified – paintings by Tanning and Man Ray were donated by Copley, whose own work was also accepted as a gift by the museum. Even if surrealism has occupied a rather marginal position in canonical accounts of American art, Tate’s important and continuing contribution to the histories of surrealism has long been evident in the museum’s American collection.

Transnational states

From the outset, Refiguring American Art sought to consider how works in the Tate’s collection manifest the exchanges that shaped the history of modernism. Exploring the history of American art through the Tate collection requires attention to the mobility of its artists and their complex and shifting national positions. While Tate has conventionally understood earlier artists such as Thomas Copley, John Singer Sargent and James McNeil Whistler to be British artists, these and other transnational figures might equally be absorbed within the rubric of American art. At the same time, such ambiguities provided opportunities to explore the transnational intersections that their practices involved. As Caroline Riley explains of the presentation of Sargent, Whistler and Mary Cassatt as the ‘expatriate triumvirate’ in American Painting from the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day at Tate in 1946, the presence of these artists served the curatorial interest in ‘locating cultural convergence in American and European art’.12

The firmly international character of early-twentieth-century sculptural idioms, and the active involvement of Americans in their mainstreams, is evident in the acquisition of works by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Andrew O’Connor and Herbert Haseltine by the museum; American contributions to aesthetic painting were made clear in the presence in the collection of paintings by Henry Muhrmann and Neville Cain. The complex realities of Tate’s collecting of American artists’ work are drawn out in new summary texts on such artists. Anglo-American relations are only further complicated by Tate’s acquisition of Robert Henri’s Market at Concarneau 1899, acquired alongside works by Jasper Johns and Mark Tobey in 1961 and providing an unmistakably transnational origin for Tate’s emerging story of American art. Such works are today more readily absorbed into displays at Tate Britain than Tate Modern. However, as they neither seem to advance the frameworks of modernism nor fit the constraints of a national art history, the presence of such artists in Tate’s collection troubles the tendency for museums outside of the United States to present the achievements of twentieth-century American art as a strictly post-war phenomenon.

Fig.8

Barnett Newman

Adam 1951–2

Tate T01091

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Differences in understanding of the American canon when viewed from different geographical perspectives emerge across Refiguring American Art. For example, Aaron Rosen notes that while Bernard Perlin might be a ‘mere footnote’ in ‘American accounts of American art’, he can occupy ‘a much more prominent place in the history of American art as narrated on the other side of the Atlantic’.13 Such differences are in no small sense the direct result of the presence of his painting Orthodox Boys 1948 in Tate’s collection. James Finch describes the impact of the addition of Barnett Newman’s Adam 1951–2 (fig.8) to the exhibition The New American Painting, and Newman’s resulting influence on a generation of British geometrical abstract painters. Such effects are not unidirectional either, with local art practices reflecting the reception of foreign artworks. This is why Theodore Roszak acquires new meanings in relation to the so-called ‘Geometry of Fear’ sculptors of the 1950s, and why understandings of the geometrical abstractions of Sue Fuller, as Frances Follin explains, were inflected by new, if ultimately misplaced, reverberations in the wake of the British artist Bridget Riley.

Borders between British and American, local and foreign, are repeatedly contested throughout the project. When Sophie Cras finds, in the work of Larry Rivers, evidence of ‘the fundamental mutations of American art in an international context in the early 1960s’, her judgement as much concerns the experience of the artist and the content of his art as it does its circulation and reception in and beyond the United States.14 Natalie Adamson’s account of Sam Francis’s Around the Blues 1957, 1962–3, counters any sense that his art might be straightforwardly absorbed into the American canon by outlining his affiliations with abstract painting in post-war Paris. But this is true not only of works made, as in Rivers’s case, beyond the borders of the United States. When Sophie Halart seeks to locate Liliana Porter’s Wrinkle 1968 within the more politically engaged tendencies of Latin American conceptualism, it matters little that the work was made in New York; the capacity for works to transcend the nation concerns more than just the artist’s biography.

Perlin’s painting is one of several artworks explored in the project that were shown in major European exhibitions (others include Noland’s Gift, Lewis’s Cathedral, Newman’s Adam and Hoffman’s Pompeii), and the reconstruction of each of these instances confirms the importance of such contexts to the reception of American art in Europe. Even though the framework for the project might support deeper consideration of the interactions between the United States and Britain, the treatment of these geopolitical frameworks here has insistently presented these ideological contests in more multilateral terms. Claire Brandon’s positioning of Norman Lewis’s Cathedral 1950 as it was shown at the Venice Biennale within the coexisting spheres of national promotion and transnational dialogue paints a particularly vivid picture of these dynamics, especially the geopolitical boundaries and hierarchies that Brandon shows to have been at stake in the Euro-American art world of the 1950s. In the case of Theodore Roszak’s The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952, Tate was itself the host for the competition to build a monument to political prisoners, one of the earliest and most boldly political of these initiatives. Surveys of such key exhibitions by Caroline Riley and Frank Spicer recover the more complex ideological entanglements of other exhibitions of American art hosted by Tate in the 1940s and 1950s, including American Painting from the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day (1946), Modern Art in the United States (1956) and The New American Painting (1959).

Such forces were also the focus of a workshop titled ‘Marshalling American Art: Exhibiting Ideology in the Cold War’, co-organised with Julia Bailey. In bringing together new research into the position of American art in Europe during and after the economic stimulus of the Marshall Plan, participants in the workshop contributed to an increasingly complex understanding of the differing local contexts through which such ideological contests unfolded. The workshop also exposed the multiplicity of state and non-state actors involved in the contests, and the varying degrees of success met by their political imperatives. In the papers from this workshop, and in In Focus texts by Brandon, Cras, Rafaelle Bedarida and others, it is clear that these are histories that cannot be separated from either the curatorial programmes or individual works of art that they involved. A more interpersonal view of transnational practice was pursued in the ‘Special Relationships: American Artists and their Collaborators’ workshop, co-organised with Matthew Holman. This considered how collaborative and collective artistic practices were able to transcend the limits of place and personhood.

Given the more complex ideological contests staged in multinational exhibitions, or even in the expansive touring itineraries of American exhibitions, the identification of the American-ness of post-war American art looks rather less secure than it might once have appeared. Katherine Kuh’s exhibition American Artists Paint the City (1956) at the Venice Biennale is a useful example here, and not simply because two of the strikingly diverse works it contained (by Perlin and Lewis) are now in Tate’s collection. Like many exhibitions of the 1950s, Kuh’s display prioritised stylistic diversity over the soon-to-be canonised victories of abstract expressionism that would come to dominate narratives of this field, and to which they ultimately contributed. But as the possibility for these two very different visions of American modernism came to co-exist within a more pluralistic understanding, the triumph of American abstraction was rather more fitful than its art historical imagining came to suggest.

To understand abstract expressionism as the materialisation of American individualism should not, however, distract from its position within a broader field of transnational practices of abstract painting. It represented, as Emily Warner puts it in her project on Hans Hofmann’s Pompeii 1959, ‘not an American idiom but a global Esperanto’.15 This has a biographical element too, because so many of the artists considered here were born outside of the United States, or spent significant time beyond its borders. It is thus rarely sufficient to understand their work as a manifestation of national artistic tendencies, much less character. When AnnMarie Perl uses Kline’s Meryon 1960–1 to return to this artist’s experience in 1930s London, she reveals an artist whose eventual association with a distinctly American industrial imagery was sharpened by his ‘immersion in a foreign culture’ that ‘may have made his native culture seem new and strange’.16 In this context, Kline’s titling of Meryon can thus be understood to describe his ‘take on French tradition’, but also serve (as the contribution to this project by Eugenia Bogdanova-Kummer details) as a record of his engagement with Japanese calligraphy.

Ultimately, it was the transgression of national borders that seemed to provide the most timely focus for the Refiguring American Art conference. Titled ‘Border Control: On the Edges of American Art’, the theme embraced the overlaps across geographical and other borders. When the title for this conference was formulated in 2016, it was assumed that its nod towards then-candidate Trump’s mooted border wall, and the crude isolationist and anti-immigrant sentiments for which it stood, would become the stuff of history. By the moment of the conference itself in May 2017, in the era of Trump and Brexit, it instead reinforced the importance of an art and an art history engaged with the social sphere; it was a reminder of the fragility of the liberal, democratic values on which the successes of modern American art were built – even when its practitioners operated quite outside the dominant culture, or at the least imagined that they did. This context provided a reminder that political ramifications of a transnational art history, reliant as it is on the motion of artists (and art historians), depend upon the possibility of mobility, privileges that should not be taken for granted.

Multiple temporalities

The varied authorial perspectives of the In Focus structure inherently advance an understanding of artworks that underlines the insufficiency of stable and singular meanings, embracing a more plural understanding of their meanings across space and time. As many of the research projects reveal, complex and multilayered temporalities are also manifest within works of art themselves. As Michael Leja explains in his contribution to the In Focus project on Barnett Newman’s Adam 1951–2, the biblical references of this work are not simply a way to thematise the artist’s focus on the significance of new beginnings. They also set forth a vision of creation that disrupts conventional temporalities in order to span and connect vast gulfs of time, between the primitive and the biblical, and the more contemporary cataclysms of the Second World War. This concern with time emerges across this project as fundamental to the formal properties of Newman’s work, and the kinds of viewing it encourages.

Fig.9

Isamu Noguchi

The Self 1956

Tate T00338

© reserved

Several of Tate’s early American acquisitions engage the existential crises of the immediate post-war decade. One example from outside the In Focus research projects comes to mind. Isamu Noguchi’s The Self 1956 (fig.9), included in the Reconfiguring American Art display at Tate Liverpool, originated in a work titled Genshi Jin. As the artist explained in a letter to Tate, this Japanese phrase ‘meaning “original” or “modern” man … has the added modern meaning of Atom’, such that he also took it to mean ‘The Atomic Man’.17 As with the inclusion of works by Newman, Mark Rothko and Lee Bontecou in this display, Noguchi’s sculpture engaged the potential collision of past and present augured by the nuclear age. Robert Slifkin describes Roszak’s The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952 as a monument ‘created for an uncertain future in which the question of the remembrance of the past seemed less crucial than the present survival of humanity’.18 In the case of Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948, as Erika Doss’s contribution to this project details, the content of the painting engages the visual cultures of marginality and discrimination in the United States as much as it may also point towards the millions murdered in the Holocaust. Within works such as these, spatio-temporal leaps and folds allow artists to grapple with the profound human upheavals facing the post-war subject.

Furthering the transnational narratives of artists and artworks highlighted in Refiguring American Art, several authors have emphasised the capacity for artworks to coalesce disparate times and places. According to AnnMarie Perl’s account, the title of Kline’s Meryon 1960–1 punned on the name of a nineteenth-century printmaker while simultaneously pointing towards the location of Alfred Barnes’s collection in the exclusive town of Merion, Pennsylvania, and in so doing, the very different landscapes from the artist’s own upbringing in Pennsylvania coal country. To similar ends, Blakinger’s reconstruction of the history of the Sixth Avenue parking lot chosen for Oppenheim’s Salt Flat 1968 makes it clear that this was no mute tabula rasa, but instead served as the nucleus of an allusive network of interconnected sites far beyond New York City – from the military installations in Dugway, Utah, to the salt pans of Great Inagua in the Bahamas. Ultimately, the redevelopment of the downtown Manhattan site into luxury apartments can also be drawn into the expansive spatial and temporal flows engaged by Oppenheim’s work.

Such questions have not been merely philosophical for post-war publics. Several works considered in Refiguring American Art engage with the politics of the Cold War through the narrative conventions of science fiction. Such reverse temporalities imagine the future as a return to a mythic, primordial past, such as that explored in Robert Slifkin’s text and my own concerning Roszak’s The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952. Other In Focus projects pursue the possibility for artworks to stage these kinds of transhistorical contacts in more specifically socio-political frameworks. In this context, the receding train tracks of Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948 depict downtown New York, but they also point towards Auschwitz. Elsewhere, the translated labels in Rivers’s Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961 register the objectification of women’s bodies, and also allude to the significance of mapping and naming to colonisation. The polyvocal possibilities of these artworks, as these examples suggest, were sharpened by the effort to locate their meanings within the international contexts that shaped their production.

At the ‘Border Control’ conference, the resonances between the past and the present were a recurrent theme. Not wishing for a history of American art refracted through the exigencies of the present, the value in thinking historically was posed not simply as an escape from the hurtling pace of the current news cycle. For those interested in the artistic manifestations of the New Deal, or the Cold War, or the ‘New Frontier’, or the ‘Great Society’, or the ‘Clash of Civilisations’, or the End of Ideology, or even of History itself, the political dimensions of the American century and the purported ‘triumph’ of its art seemed especially relevant as the aesthetics of the present moment congealed, creating their own myths, drawing eagerly on an imaginary past, and undoubtedly leaving their mark on contemporary cultural production.

Material encounters

Fig.10

Louise Nevelson

Black Wall 1959

Tate T00514

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Given the object-centric nature of the In Focus format, it is not surprising that the twenty or so projects all deal with the form of the artworks in great detail. What the close study of a single work further demands, however, is attention to facture and process. Across many contributions to the project, the histories of making and studio practice embedded within a work of art emerge as fruitful interpretative sites. One of my most memorable encounters with a work of art at Tate was seeing Louise Nevelson’s Black Wall 1959 (fig.10) in storage, and discovering that its form was not what I expected from earlier photographs. Reconstructing the material history of this object emerged as a major focus for my research on this work, a strand of inquiry that would have been impossible without the first-hand access to artworks that this broader initiative made possible. Visiting works of art in the gallery and in storage with contributing authors was an especially rewarding aspect of Refiguring American Art.

Many scholars have drawn upon the groundswell of scholarship in materiality to examine the meanings produced by the varied haptic and tactile properties of artworks in Tate’s collection of American art. Elyse Speaks’s description of the ‘sensate experience’ of Nevelson’s Black Wall 1959 would be one example of this interest. ‘Nevelson’s materials’, Speaks explains, ‘retain the tactile as well as visual pleasure of their prior lives: wooden turnings arouse the sensation of grasping a chair, or running one’s hand across a balustrade.’19 Given such interests in materiality, the insights of the museum’s conservators proved especially fruitful. The interview with James Rosenquist included in the project on his work is a prime example of the insights that can be drawn from their expertise. Conducted by Rachel Barker and Tom Learner in 2009 and published here for the first time, the interview makes available invaluable insights into the making and materiality of Rosenquist’s Silo 1963–4. Likewise, interviews with Mike Mandel and Barkley Hendricks, conducted by the authors of In Focuses, extend far beyond technical art history to grapple with the material dimensions of these artists’ practices.

The research commissioned for Refiguring American Art has, appropriately enough, returned persistently to the figure. In Richard Shiff’s text on de Kooning’s Women Singing II 1966, for instance, we learn that the artist was observed ‘bending and stretching his body as he drew from memory’.20 Across the project, de Kooning’s embodied practice looms large, larger than Pollock even, and his considerable influence is described in projects on artists as diverse as Franz Kline, James Rosenquist and Kenneth Noland. Many other works in Tate’s collection of American art might be drawn into such an understanding of artworks as bodies of sorts. In the case of Noland’s Gift 1961–2, Molly Berger’s account of Noland’s engagement with the therapeutic methods of Wilhelm Reich understands his abstractions to enact something of the corporeal and muscular effects of these therapeutic regimes.21

Projects on de Kooning, Newman and Rosenquist pay particular attention to the relationships between their respective processes of revision and require us to understand artworks not simply in their complete form but as coexisting with earlier iterations and materially related works through which their layered meanings are produced. The complex history of these works was, in fact, a motivating factor in selecting these works for in-depth scholarly scrutiny. In each of these cases, the effort to track down archival photographic documentation of the prior states of these works allows such meanings to be excavated. The museum’s acquisition of a cache of new drawings by Theodore Roszak added impetus to the In Focus project on his work, and shed new light on the process and iconography that Roszak’s The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952 pursued.

Several of the In Focus projects here seek to locate the apparently autonomous art objects that are their subjects within more expansive spatial practices – Liliana Porter’s Wrinkle 1968 is considered in relation to her three-dimensional environments of crumbled paper from the late 1960s; the elements of Louise Nevelson’s Black Wall 1959 are understood within her own pioneering immersive installations of the late 1950s. As Blakinger explores in his project on Oppenheim’s Salt Flat 1968, its use of the shifting material states of salt engage systems that extend beyond the physical and temporal boundaries of the artwork itself.

Tate has now, of course, fully embraced the widest range of installation-based practices, but situating works such as these within the history of this field enriches their possibilities for productive dialogue with the large-scale installations so prominent in the museum’s displays. The installations of Nevelson’s Black Wall 1959 next to Sheela Gowda’s Behold 2009 at Tate Modern in 2015, and Noland’s Gift 1961–2 alongside Paul Sietsema’s film Empire 2002 at Tate Liverpool in 2017, exemplify the rich possibilities of such connections being materialised in the gallery space. It is relevant that much of this research unfolded at the same time as a renewed museum attention to the collection of performance art. My own contributions to the exhibition catalogue for Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture and an essay on the performative aspects of Richard Artschwager’s Table and Chair 1963–4 contributed to the presence of American art within this area of focus.22

Everyday modernisms

Across all the outcomes of the Refiguring American Art research project, authors have pursued in their own ways a vision of American modernism. It emerges as a lived, social phenomenon of vanguard artists engaged by the realities of everyday life in post-war America, and of a serious modernism inextricably connected to the broader kinds of popular, commercial and mass media forms within which works of art circulated. From Perlin’s engagement with the ballet, to Noland’s enthusiasm for jazz and Matta-Clark’s culinary endeavours, the artists highlighted within In Focus projects have been shown to pursue an approach to modernism that was deeply embedded in the activities of everyday life.

The influential role of popular culture that cuts across many of the In Focus projects demonstrates the relevance of questions of reproduction and circulation to many of these artists. Entertainment and advertising were especially formative reference points for many of the works included, and the resultant texts have sought to place relationships between high and low at the heart of their account of American vanguards. Anna Arabindan-Kesson convincingly shows, for example, how Barkley Hendricks’s Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974 capitalised upon the aesthetics of ‘blaxploitation’ films, and the reinvigoration of art nouveau, to gesture towards the subcultural signifiers of black power and the sexual revolution. Elsewhere, I have attempted to relate Theodore Roszak’s tortured sculptural creature The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952 to the contemporary monsters of science fiction and film.

Technologies of visual reproduction are omnipresent across the project, and not just in the works that involve print-based media. In AnnMarie Perl’s account of Franz Kline’s Meryon 1960–1, for instance, the artist’s enduring interest in illustration and printmaking is evident in the work’s title, which makes reference to nineteenth-century printmaker Charles Meryon. The artist’s later disavowal of such interests indicates, as Perl puts it, an understanding that it ‘risked compromising his success as a fine artist’.23 As Sophie Halart explains of Liliana Porter’s Wrinkle 1968 and her broader work with the New York Graphic Workshop, the artist engaged with radical histories of the printmaking medium, eschewing its fine art conventions to embrace commercial reproduction, distribution and ultimately disposability. In so doing, she directly challenged conventions of collectability essential to the art world and its institutions.

Fig.11

Gordon Matta-Clark

Walls Paper 1972

Tate T14658

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2019

Another reproducible medium that emerges as an unexpected leitmotif in several research projects is wallpaper, using as a productive metaphor the conventionally negative judgement of abstraction as mere decoration. Drawing on Harold Rosenberg’s fear that abstract expressionist painting would end up as mere ‘apocalyptic wallpaper’, Sandra Zalman explores how Matta-Clark’s Walls Paper 1972 (fig.11) blurs the boundaries between abstract art, newspaper and wallpaper. In Emily Warner’s project on Hans Hoffman’s Pompeii 1959, the artist’s interest in the mural provides a historical basis for an understanding of his art as a kind of modernist wallpaper, in line with his aspirations for an art that would ‘become an enjoyable part of life’.24 In her contribution to the same project, Elissa Auther’s exploration of the status of decoration in relation to Hoffman’s reputation reveals how such contexts have served to undermine the seriousness of his art by virtue of their allegiances to the feminine and the commercial.

The connections between particular artworks and the specific meanings of local sites emerge as a counterbalance to transnational interests in projects that ground the artworks they explore within the urban spaces in which the works were made. Sandra Zalman’s attention to the relationship of Matta-Clark’s Walls Paper 1972 to 112 Greene Street, Samantha Baskind’s account of the evocation of the Jewish urban spaces of the Lower East Side in Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948, or my own interest in the demolished Kips Bay studio at 323 East 30th Street engaged by Nevelson’s Black Wall 1959, all highlight the close relationship between these works and particular spaces in Manhattan, exploring artistic responses to the social effects of urban redevelopment. As Philip Ursprung suggests more generally of Matta-Clark, his work serves as a theoretical alternative to the urbanisation and progress narratives that dominate architectural studies, offering an alternate vision of ‘decay and collapse’ that surveys the spatial experiences of deindustrialisation.25

The relationships between abstraction and the ideologies of capitalism is another recurring theme that emphasises how even the most apparently formalist and autonomous forms of abstraction gesture towards the commercial realities of the post-war world. My own account of Kenneth Noland’s Gift 1962 suggests that his mode of ‘one-shot painting’ was conceived not simply as a formal language but as a way to conform to efficiency drives of the post-war world.26 In her account of Jennifer Bartlett’s Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972, Kirsten Swenson explains that the artist’s use of modular enamel panels as a painting support can be understood in similar ways: ‘Bartlett’s plates are diverted from familiar consumer and public usage, and exist in her work as fragments of those things – the signs, bathtubs or refrigerators that fulfil a function in modern industrialised society’.27

The dream of an efficient art is a theme that emerges in the projects on Rosenquist and de Kooning, too, dealing as they do with the apparently unproductive labour of artistic revision. These artists’ use of ‘found imagery’ is another means by which artistic productivity is examined, with the use of television source material for de Kooning’s Women Singing II 1966 and the advertising imagery in the painted collage of Rosenquist’s Silo 1963–4 providing ready models for a figurative art based on widely circulating sources. The status of consumer capitalism as a key interest for vanguard artists emerges as a key theme across Refiguring American Art – through the political valences of de Kooning’s performed spontaneity (or their fond parody as models of inefficiency by James Rosenquist), and through the more firmly satirical gesture of Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s mock corporate identity.

The movement of people across borders is closely connected to the circulation of goods, including the trade in works of art. For the In Focus projects brought together here, scholars have had access to commercial information concerning the sale of works of art to Tate that often reveal aspects of their value and exchange excluded from art historical study. Attending to such transactions helps us move beyond the fictions of autonomy that continue to shield art from consideration as part of a wider field of exchangeable commodities. ‘Visible Hands: Markets and the Making of American Art’, the third workshop of the project, brought together papers exploring the operation of markets in art historical terms. It favoured scholarship that sought to locate the forces of the market in the visual and material form of the artwork itself, or to understand the role of economic transactions and systems in the formulation of taste, and the art historical canons it produces.

The questions outlined here are not unique to American art but, as it came to dominate the global art world, it nonetheless provides a rich territory within which to explore them. Running through all elements of Refiguring American Art has been an understanding of the societal role of art and artists, and a vision of modern art as a useful, even everyday enterprise. But the fear of an art world compromised by the institutions that sustain it has run alongside this. Both have concerned artists as much as they do art historians, and it is in aid of such anxieties that the vision of American art advanced by this project seeks to transgress some of our own boundaries – between disciplines, movements, times, nations or periods, and between the strictures of the avant-garde and its others.