Fig.1

The King and Queen examining John Singleton Copley’s painting The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781 1783 at the Tate Gallery exhibition American Painting: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day, published in Illustrated London News, 22 June 1946

The present Exhibition – perhaps the most representative collection of American painting ever assembled, containing as it does masterpieces from America and Great Britain never before hung side by side – will give the people of Great Britain a unique opportunity of becoming acquainted with a fascinating and rapidly developing school of painting hitherto scarcely known among us.

John Rothenstein, ‘A Note on American Painting’ (1946)1

From 14 June 1946, a little over a year after the British fêted the success of the Allies in the Second World War, and continuing until 5 August 1946, the Tate Gallery in London hosted its most comprehensive display of American painting to date. Coordinated by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and consisting of approximately 250 works, the exhibition, American Painting: From the Eighteenth Century to Present Day (hereafter referred to as American Painting), celebrated the renovation of the Tate Gallery after the bombing campaigns that had battered London and its residents. Employing the paintings as diplomatic tools, the display demonstrated the continued collaboration between Britain – a rebuilding nation – and the United States – a nation rising in economic stature. The exhibition put into sharp relief the collegial diplomatic relationship between the two once-warring nations and the eclectic aesthetic styles in American painting that signified its cultural independence from British painting. Loaded with artistic and diplomatic import by curators and politicians, the exhibition captivated the British, attracting approximately 100,000 visitors including King George VI and his wife Queen Elizabeth.2 Previewing the display the day before its opening to the public, the royal pair explored the exhibition privately for over an hour according to press accounts. To the general public, the power of the monarchs to bestow value on the exhibition was a clear instance of ‘time spent’ equating to ‘cultural worth’.3 A photograph in a pictorial entitled ‘Lest We Forget: Memorials of War, and Events of Peace’ from the 22 June 1946 issue of the Illustrated London News documented the royal visit and simultaneously promoted the exhibition (fig.1).4 Despite these diplomatic aspirations, the American art on display proved as difficult to wield as a political tool in this post-war moment as it had as propaganda during the war.

In order to examine the motivations behind the decision by Tate Gallery curators to host the 1946 exhibition, this essay explores the canonisation of American painting through its presentation at the Tate Gallery, its politicisation by both governments, and its reception by the American and British press. Without interpretive labels, many of the approximately 250 paintings illustrated American life and culture without overtly referencing the Second World War. This essay argues that the intention was to document the distinctive qualities of American culture. Nevertheless, the subject matter and style of nearly half of the paintings on view confirms that the purpose of the exhibition was to articulate, at least in part, the complicated role of art in the interdependent historicising of violence and recovery of culture after the trauma of war. On the walls of the Tate Gallery, the selected paintings wrestled with the impact of six years of sustained conflict.

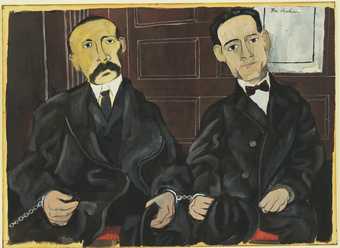

Fig.2

Ben Shahn

Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco 1931–2

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

As Rothenstein makes clear in his short catalogue essay, central to this discussion of American painting was the notion of masterpieces and the process of canonisation. Fundamentally, his essay seeks to understand which paintings could best visualise not only the history of American painting, but the history of two nations within the contested peace of 1946. Reviewing the catalogue, it is clear that select paintings documented the rupture of the perceived interwar stability of American and British culture with chaotic images. For example, this disintegrating stability could be framed in the failing of democratic institutions, as Ben Shahn imagined it in Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco 1931–2 (fig.2) – a painting of two immigrant men who were convicted of murder and executed in 1927 on the basis of fragmentary and unreliable evidence. Given that each nation rejoiced at the end of the war, how did the paintings in this exhibition proclaim a sense of recovery and, more precisely, a form of recovery that promoted sustained peace? The discussion that follows examines the history of American painting on view at the Tate Gallery in order to consider the rupture of perceived interwar stability, the historicising of the Second World War through previous battles and the recovery of both nations. It examines how the paintings promoted the primacy of the Western art canon and the challenge of post-war Anglo-American cultural diplomacy as the United States gained hegemonic ascendancy.

The royal visit

Fig.3

John Singleton Copley

The Death of Major Peirson, 6th January 1781 1783

Tate N00733

Fig.4

Ivan Albright

That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door) 1931–41

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

© The Art Institute of Chicago

Fig.5

Hyman Bloom

The Synagogue 1940

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Hyman Bloom Estate

According to press accounts and the three accompanying publicity photographs, the King and Queen were particularly interested in three paintings. In the most widely distributed photograph (fig.1), the group stands before John Singleton Copley’s The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781 1783 (fig.3). With dramatic chiaroscuro and twisting figures, the stage is set. Copley portrays in heroic terms the Battle of Jersey, one of the last conflicts on British soil, which was fought between British and French forces in 1781.5 The location of the battle is significant. The Isle of Jersey, as part of the Channel Islands, demonstrated its geographic weakness and the mutability of borders once again when German forces occupied the island during the Second World War. The British army’s ability to resist the 1781 French invasion took on renewed meaning in 1946. The painting, displayed 162 years after its completion, demonstrated the sacrifice of British soldiers for centuries. Within the context of 1946, it served to historicise the Second World War for the Tate Gallery’s viewing public. The second painting favoured by the royal pair, Ivan Albright’s That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door) 1931–41 (fig.4) – with its claustrophobic details, its meditative title and its impasto serving as a form of visual rubble – summarised the anxiety of the British public after years of living in the man-made hellscape of war. Lastly, the esteemed group contemplated Hyman Bloom’s The Synagogue 1940 (fig.5), a painting embodying the mysticism of Judaism as both beautiful and different from the monarchs’ own Anglican religious services. This artwork, completed by the Latvian-American painter during the Second World War, forced visitors to confront their own ideas about the Jewish faith and its people as set against the propaganda promoted by the Nazi Third Reich and perpetuated in other countries. Together these three paintings embodied the relationship between the two nations, the impact of war on the public’s psyche and the religious values of the Jewish people.

Framing the royal couple in the press photographs are John Rothenstein, Director and Keeper of the Tate Gallery and author of the catalogue’s principal essay mentioned above, and John Walker, the Chief Curator of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and primary organiser of the display. Also in attendance were the US Ambassador William Harriman and the Hon. Jasper Ridley, Chairman of the Tate Board of Trustees. According to the journalist for the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Mercury, it was the ‘energetic and enthusiastic’ Walker who ‘took obvious delight in pointing out to their Majesties the beauties – mainly, it is true, unknown to us – of America’s pictorial art’.6 While approximately thirty other museum and government staff supported the exhibition, the international partnership of Rothenstein and Walker proved to be essential to the organisation and success of American Painting.

It is important to remember that the Tate Gallery’s strong American art collection began in 1914 and grew exponentially in the late 1950s. Despite the desire to build up this part of the collection, however, the process of fostering a dialogue across nearly 3,000 miles of ocean was a challenge for the museum’s curators, donors and trustees. During the interwar period this transatlantic exchange was impeded by Tate Gallery Trustees’ decision to reject a 1931 bequest by the powerful American donor Lillie Bliss, co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and by Tate Gallery curators’ inability to display MoMA’s Three Centuries of American Art in 1938 due to the small size of the galleries and an already-scheduled exhibition of Canadian art (Three Centuries was shown in Paris at the Musée du Jeu de Paume in May–July 1938 and returned to the United States instead of travelling to the Tate Gallery). Notwithstanding these decisions, the Tate Gallery made strides with a 1935 exhibition of Paul Manship’s art deco-inspired sculpture and the acceptance of other gifts of American art, such as the New York regionalist Charles Burchfield’s nostalgic watercolour Freight Cars in March 1933 (Tate N04833), which entered the collection in 1936.7 Although ultimately not installed in London, the curatorial discussions between MoMA and the Tate Gallery regarding the large 1938 exhibition Three Centuries of American Art, which featured architectural models, drawings, films, photographs, prints, sculptures and vernacular artworks as well as painting, served as the fertile ground from which the 1946 exhibition grew eight years later. Indeed, the rehanging of thirty artworks in American Painting that had been shown in Three Centuries of American Art reaffirmed the history of American art that had been displayed in Paris at the earlier exhibition. During the intervening eight years, the war had precluded a large-scale exhibition because of an inability to coordinate loans and the unwillingness of government bodies to divert military funds, although the Tate Gallery did manage to send artworks to MoMA for safety during the conflict.

Art’s role in popular diplomacy

After the failed attempt to display an American art exhibition in 1938, Tate Gallery staff revived the idea of such an exhibition in 1944, believing that the fighting would soon end and that the six galleries that had been damaged in the conflict would be rebuilt. Early in the exhibition discussions, American and British diplomats and officials, including US Secretary of State James Byrnes, as well as members of American organisations such as the Art Advisory Committee, Division of Cultural Cooperation, Allied Control Commission for Germany, Office of Public Information and Office of War Information (OWI), expressed their desire to support the exhibition, if not monetarily then through their far-reaching international networks. After the Tate Gallery decided to host an American painting exhibition, it was the US Department of State and the Overseas Branch of the OWI that determined that the exhibition should be organised by the newly opened National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, D.C.8 In an August 1944 letter, Charles Thomson, Advisor to the US Office of Public Information, wrote to the first Director of the NGA, David Finley Jr: ‘May I say that the Department views this initiative [the Tate Gallery exhibition] with approval and is pleased to learn that the National Gallery is receptive to the suggestion that it assume responsibility for collecting the paintings in this country.’9 In 1945, as planning began in earnest, the question remained as to how the NGA would fulfil the political needs and artistic aspirations of the exhibition. Finley contacted John Brown, who worked as the American Advisor on Art to General Eisenhower and for the Allied Control Commission for Germany, to ‘have a preliminary talk about an art program for Europe, so that our [Advisory] Committee can make a report to the State Department’s Art Advisory Committee’.10 Finley requested that Brown ‘send me suggestions as to what, he thought, it might be desirable to do through the Department of State’.11

The correspondence confirms the early political impetus of the exhibition.12 Indeed, as early as autumn 1944 diplomats hoped for an American painting exhibition. In October of that year, American Ambassador to Great Britain John Winant, who maintained a close relationship with Prime Minister Churchill, cabled Ferdinand Kuhn Jr, Deputy Director of the Overseas Branch of the OWI. In the telegram Winant confirmed that he was:

definitely in favor of an exhibition of American painting for [the] Tate Gallery as soon as possible after the end of war in Europe. Believe it is good psychology as American gesture of congratulations to England as she ceases at last to be a battle-ground and peacetime activities are resumed as far as possible. Cultural exchange of the highest order is an important part of our contribution … I feel that this is a particularly good time for American art to be actively represented.13

The message corroborates the exhibition’s role as a diplomatic tool for the two nations and, specifically, as a tool for promoting peace. The desires of these politicians mirrored the NGA advisory committee’s own understanding of American art’s purpose as a representation of the United States in London. It was the NGA committee that needed to select and invest American paintings with the status of masterpieces. Finley confirmed this viewpoint, writing to Edgell:

It must be representative of the best we have produced in this country … The Tate Gallery Trustees would like to have the exhibition held as soon as possible after the war in Europe comes to an end, without waiting for the conclusion of the war with Japan. Our Ambassador at London, Governor Winant, strongly supports this point of view as you will see by the enclosed cable.14

As a means of building its political significance, Edwin Kenworthy from the British Division Overseas Branch requested exhibition details on behalf of Rothenstein in order for him to discuss it at the American-organised 1944 exhibition Artists for Victory at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh.15 In order to facilitate communication, the British made available the Army Essential Mail, its telegraph wire, and coordinated a special official passport in order for Walker to travel with the art to London.16 The politicisation of American art was not new, however. At the same time that the Department of State supported the NGA and the Tate Gallery’s project, State staff produced its first curatorial endeavour, Advancing American Art, which first went on view in 1946, travelling for five years in Europe and Latin America, and has been the subject of much scholarly attention.17

Behind the scenes: Collaboration and challenges

The scale of American Painting and its international nature required that staff work collaboratively. At the Tate Gallery, Rothenstein and his assistant Robin Ironside oversaw the artworks’ installation at the museum. In response to the invitation from the Tate Gallery, Finley and Walker decided to set up an advisory committee from ‘the foremost museums in America’ located predominately in the Northeast and Great Lakes area.18 Headed by Walker, the historical paintings selection committee consisted of George Edgell, Director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Fiske Kimball, Director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and Francis Henry Taylor, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Duncan Phillips, founder and Director of the Phillips Memorial Gallery in Washington, D.C., headed the modern paintings committee composed of Alfred H. Barr Jr, founding Director of MoMA; Juliana Force, founding Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; William M. Milliken, Director of the Cleveland Museum of Art; and Daniel Catton Rich, Director of the Art Institute of Chicago.19 Rothenstein was pleased by the inclusion of MoMA no doubt because of Barr’s previous contact with the Tate Gallery in 1938 regarding Three Centuries.20 Serving as a loose division point between the historical and modern categories in the exhibition was the famed 1908 Macbeth Gallery’s exhibition of the avant-garde Ashcan School of painters. The decision to emphasise the Macbeth Gallery instead of the subsequent 1913 Armory Show was likely twofold. First, the Macbeth exhibition displayed only American art, and secondly, the gallery was a less powerful intellectual entity than the influential Armory Show, such that curators in 1946 could make use of the Macbeth exhibition in their narrative without closely adhering to the commercial gallery’s interpretation of the painters.

The ongoing war, further complicated by the active bombing of London, meant that organising the exhibition required the cooperation of the American and British governments.21 The American Office of War Information and Department of State agreed in part to ‘defray the cost of packing, assembling and subsequent dispersal of the exhibition’ and the Tate Gallery Trustees covered costs once the paintings were loaded aboard the SS Queen Mary in New York City until the crates were unloaded in New York City again.22 The Tate Gallery also paid for the printing of a catalogue.23 In total, American museums, government agencies and private donors paid $6,141.40 and their British equivalents paid approximately $26,000 in order to install the exhibition – a vast sum made all the more significant considering the debts associated with the war and the necessary rebuilding of infrastructure.24 That the British allocated over four times the amount the Americans did confirms the Tate Gallery staff’s investment in the exhibition.

The selection of artworks required careful negotiation with museum boards and private collectors. The NGA American advisory committee selected paintings previously on display in Paris at the 1937 Exposition Universelle and the 1938 Three Centuries of American Art. Their inclusion in the London exhibition thus further cemented the canonisation of specific artworks as they were displayed internationally.25 Rothenstein was quite clear that ‘we should like the Exhibition to be composed on aesthetic lines, that is to say, we would prefer it to have the character of a collection of masterpieces rather than an historical survey’.26 His request reinforces the importance of American masterpieces for the Tate Gallery and the flexibility of the term as the canonisation of American art continued during the 1940s. After reviewing an initial list from Walker in 1945, Rothenstein shared his preferences through an amended list that highlighted a more romanticised view of the landscape (with an additional Albert Ryder) and a heroic vision of British warfare (with Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe 1770, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa).27 Further complicating the history of American painting that the NGA created for an international audience was Walker’s inability to successfully obtain the loans he requested.28 For example, he failed to acquire Thomas Eakins’s Gross Clinic 1875 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia), John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence 1817–19 (United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.), Raphaelle Peale’s After the Bath 1822 (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), Thomas Sully’s Thomas Jefferson 1821 (United States Military Academy, West Point) and Gilbert Stuart’s Mrs. Perez Morton (Sarah Wentworth Apthorp) c.1802 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). These paintings would have illustrated the United States’ early government, noteworthy citizens and the important role of teaching hospitals, as well as the technical innovations in painting during the nineteenth century.29 Following a different model than MoMA had when it chose an all-inclusive definition of American art for Three Centuries of American Art, Finley wanted to limit the artworks to paintings and Walker suggested the inclusion of watercolours.30 In the end, the curators represented approximately 118 male painters and 5 female painters with the display of between 240 and 252 artworks.31

Building narratives on walls and with words

Fig.6

Edward Hicks

Peaceable Kingdom c.1834

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Fig.7

John Atherton

Christmas Eve 1941

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of John Atherton

The decision by Tate Gallery administrators to select the NGA as their American partner was not wholly based on the museum’s more conservative aesthetics in comparison to New York museums such as MoMA, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum or the Whitney. The NGA was too new for that to have yet been determined. That Finley selected Duncan Phillips, owner of the avant-garde Phillips Memorial Gallery, to head the contemporary painting committee confirms his comfort in promoting innovative artistic approaches. Rather, when contacted by the Tate Gallery, the American State Department and OWI sought a museal proxy equivalent to the Tate Gallery as the nation’s art repository and suggested the NGA.32 Daniel Catton Rich, in a letter to Finley, confirmed what was at stake in the exhibition when he wrote, ‘We must make a brilliant show of it to offset what has been already purveyed in the name of American art abroad.’33 Rich’s comment was also possibly referring to the lambasting by the international press of the US Pavilion at the 1937 Exposition Universelle in Paris.34 Indeed, as the British press documents, and as will be shown below, the Tate Gallery’s American Painting: From the Eighteenth Century to Present Day was in fact met with success.35 At its close, Rothenstein wrote to Finley that the exhibition was ‘greeted with the utmost interest and enthusiasm in London’.36 To uncover what image of the United States greeted the British viewing and reading public requires exploring the artworks on view and their interpretation in the essays and lectures written by Rothenstein and Walker.

Early in the planning, Tate Gallery staff knew that they wanted the exhibition to be representative of American painting across centuries.37 Many members of the NGA advisory committee pulled heavily from their own museum collections. For example, of the twenty-three works from MoMA’s collection, Barr chose to highlight vernacular works including Edward Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom c.1834 (fig.6). In it Hicks depicted the early colonial settlement of Pennsylvania in terms of Quakerism, a faith advocating peace that was made more problematic by early Quaker William Penn’s acquisition of land from the Lenape Nation. Barr also included more recently completed works such as John Atherton’s Christmas Eve 1941 (fig.7). Described by the British press as ‘a bullet-riddled car on a deserted waterfront’, the painting showed the religious holiday in sharp relief against a poverty-stricken neighbourhood.38 The Phillips Memorial Gallery lent twenty-three paintings and emphasised the work of John Marin and Maurice Prendergast, the latter connecting the United States with Europe through Prendergast’s Venetian sojourns.

While American museum directors and curators made the final selections, Rothenstein and Ironside arranged the paintings and consequently chose the intellectual categories of American art. They organised artworks roughly chronologically and hung paintings by the same artist in the same room but not necessarily beside one other.39 Employing Three Centuries of American Art as a model, they made use of moveable partitions to increase the wall surface and better gather artworks into themes. However, according to Walker in a letter to Barr, ‘the shortages in England prevented them from acquiring the necessary materials, and as a result they found they had asked for more paintings than they could show’.40 Specifically, he noted that ‘ten or twelve paintings [had to] be kept off exhibition for a few weeks and then substituted for other pictures’.41 Furthermore, it was Walker who suggested a staggered hang in the modern section (determined as work made post-1908). The tight physical grouping of paintings required a close aesthetic or cultural relationship between the works. Despite these frustrations, Walker proclaimed the Tate Gallery curators’ accomplishment in installing the exhibition, writing, ‘I think they did an heroic job to make the exhibition look as well as it did … [and] people liked it.’42

Fig.8

Robert Feke

Isaac Winslow c.1748

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Fig.9

Ben Shahn

Liberation 1945

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Ben Shahn/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2019

The twenty-three-page catalogue, with a short essay by Rothenstein and eight half-tone photographs of the artworks, was hardly what the Tate Gallery and the NGA had originally envisioned.43 A more ambitious catalogue could not be created due to limited staff, mounting exhibition debts and a paper shortage in Britain.44 As Walker explained to Barr, ‘At a time when [British officials] are having difficulty finding enough foreign exchange to buy sufficient food, they spent $30,000 to show our paintings in London, a large per cent of this amount being in dollars to cover the insurance.’45 Furthermore, the Tate Gallery hoped that two texts on American painting by Avon Press and Penguin Books might serve as a type of ‘extended catalogue’.46 This information was relayed to American lenders who questioned the decision of a limited catalogue, a disappointment that was no doubt felt more acutely owing to the fact that the exhibition was not on view in the United States despite the extensive loans.47

Codified by the American advisory committee, the history of American painting illustrated communities that the perceived interwar cultural stability had ruptured, the historicising of trauma (since this was not the first time either nation had suffered the carnage of war, even between themselves) and the hope by local communities for a more stable future through the post-war recovery process. From beginning to end, the changing American landscape was of central concern. The artworks ranged in date from 1748 with Robert Feke’s Isaac Winslow (fig.8) – placing the mercantile business owner in the slowly shifting landscape – to 1945 with Ben Shahn’s Liberation (fig.9), which depicts children exuberantly playing despite the shelled cityscape that surrounds them. With these two paintings, the landscape shifted from an ecosystem to be controlled to a manufactured environment to be rebuilt; from a battle against nature to one between people.

In the exhibition of approximately 250 works, American culture was on full display with paintings of boxing matches and a regatta; theatrical events, music and movies; and adults strolling and children playing in city parks. The nation that the paintings described positioned the United States on parallel terms with Britain, both having survived the Second World War. The American advisory committee framed the United States as a nation of cities (twenty-six paintings depicted Boston, Chicago and New York City, among others), with their chaos and influx of immigrants, instead of being defined by its towns (six paintings), farms (four paintings) or factories (three paintings). Equally valued was the land (twenty-seven paintings), unbroken by industry or the cities’ cacophony. In contrast to the eight vernacular artworks that emphasised a perceived American iconography, twenty-eight paintings connected the United States with Europe either aesthetically or culturally.48 Three paintings by Louis Eilshemius, Charles Burchfield and Morris Kantor, all dating to the interwar period, captured the theme of the haunted house.49 Similar to Albright’s That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door) (fig.4), they cemented the idea of the rupture of perceived interwar cultural stability, of the undead still present, and of the mutability of time. As the three paintings of haunted houses suggested, both cultures shared loss and the challenge of emotionally moving forward.

Fig.10

Washington Allston (Joshua Shaw)

The Deluge c.1813

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.11

Peter Blume

South of Scranton 1931

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Estate of Peter Blume/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Fig.12

Loren MacIver

Hopscotch 1940

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Loren MacIver, courtesy Alexandre Gallery, New York

Fig.13

Eastman Johnson

Negro Life in the South 1859

New-York Historical Society, New York

More generally, forty-nine paintings grappled with the overlapping themes of disorder and meditation, whether by historicising a traumatic event in biblical terms, such as Washington Allston’s The Deluge c.1813 (fig.10), or by employing the new surrealist vocabulary as did Peter Blume’s South of Scranton 1931 (fig.11), Philip Evergood’s Lily and the Sparrows 1939 (Whitney Museum of Art, New York) and Loren MacIver’s Hopscotch 1940 (fig.12).50 Fourteen paintings explicitly tackled the theme of war in the United States and its devastation, including the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, the First World War and the most recent conflict.51 Paintings such as Albert Bierstadt’s Guerrilla Warfare, Picket Duty in Virginia 1862 (Century Association, New York) contextualised the monotony of entrenched fighting before automatic weaponry. Eastman Johnston’s Negro Life in the South 1859 (fig.13), Eakins’s Whistling for Plover 1874 (Brooklyn Museum, New York) and three paintings from Jacob Lawrence’s famed series Migration of the Negro 1940–1 were a few of the more well-known paintings that documented the racial inequality experienced by African Americans.52 Although still a comparatively small number in the exhibition, the inclusion of these paintings highlighted this topic more prominently than the exhibitions in 1937 and 1938.53 As well as these more expected themes, works depicting animals (thirty-six paintings) and specifically birds (thirteen paintings) may have been included to highlight the bestiality of war, the inhumanity of people and the desire to escape the embattled land.54

Fig.14

Robert Motherwell

Joy of Living 1934

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore

© Dedalus Foundation, Inc./Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Fig.15

Peppino Mangravite

The Song of the Poet 1944

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

© Estate of Peppino Mangravite

Aesthetically, the paintings included in the exhibition ran the gamut, from vernacular artworks and the early portraits and history paintings of the eighteenth century, to the romantic landscapes of the nineteenth century and the duelling triumvirate of international artists (Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent and James Abbott McNeill Whistler) versus those known better in the United States (Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer and Albert Ryder). To define the twentieth century, the paintings chosen encapsulated themes addressed in previous American art surveys generated by art historians. The NGA’s contemporary painting committee coordinated a dual vision to emphasise abstraction as well as a more pluralistic conception of early twentieth-century American art that combined regionalism and hyper-realism in its definition.55 They promoted abstraction with works such as Robert Motherwell’s optimistic Joy of Living 1934 (fig.14), Georgia O’Keeffe’s Pelvis with the Moon 1943 (Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach) and Man Ray’s Admiration of the Orchestrelle for the Cinematograph 1919 (Museum of Modern Art, New York).56 The curators also selected artists painting nostalgic imagery in the 1940s, including Peppino Mangravite’s The Song of the Poet 1944 (fig.15).57 Doubtless, in spite of Walker’s attempt to generate a definitive history of American painting, the exhibition’s display in 1946 – after the end of the Second World War and in a war-ravaged city – contextualises the choice of artworks and their interpretation. In 1946, the American cities these artworks documented would have appeared in sharp contrast to London’s levelled buildings.

In addition to the artworks on view, Rothenstein and Walker each wrote histories of American painting: Rothenstein produced an essay for the catalogue and Walker presented lectures at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in April 1946 and at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, in summer 1946, as well as appearing on BBC radio and television specials.58 With his opening sentence Rothenstein summarised his reductive viewpoint of American art – one also held more generally by the British – in surmising that ‘American painting began with the works of a few obscure artists who doubtless drifted to the New World through [an] inability to succeed in the Old.’59 When referencing British scholars’ investment in John Singleton Copley and Benjamin West, Rothenstein notes how radically their interpretation had changed by the 1940s, with West no longer receiving much attention.60 Of the eight Copley paintings on view, The Death of the Earl of Chatham 1779 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) and The Death of Major Peirson (fig.3) were the two with which Rothenstein sought to revive British interest in the artist.61

Rothenstein’s essay made use of some common methods of locating cultural convergence in American and European art: by pointing out the aesthetic similarities between US and European painters (in this case Gilbert Stuart was compared to Henry Raeburn and Thomas Eakins to Gustave Courbet) and highlighting American painters who depicted British elite subjects (Copley’s portraits of military conquests and the royal family and Thomas Sully’s painting of Queen Victoria both being noted).62 Equally expected in a discussion on the internationalisation of American art were the expatriate triumvirate of Cassatt, Sargent and Whistler. With four works by Cassatt, eight by Sargent and five by Whistler, Sargent clearly took centre stage in the Tate Gallery exhibition. Conversely, Rothenstein framed Homer, Eakins and Ryder as having benefitted from choosing to reside in the United States. The inclusion of ten paintings by Homer and eight works by Eakins, compared to only three by Ryder, confirms the hierarchy that was at play, with a preference by the NGA advisory committee for the perceived ‘truthfulness’ of the former two painters’ works as a nineteenth-century model.63 Beyond noting the ‘overwhelming variety’, Rothenstein did not attempt to make a qualitative judgement about contemporary art. In addition, despite the display of paintings such as Marjorie Phillips’s Emerging from An Air Raid Shelter 1941 (Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.), Rothenstein made no mention of war in his essay. It suggests a disconnection between the aspirations of the exhibition and Rothenstein’s critical assessment of American art more generally.

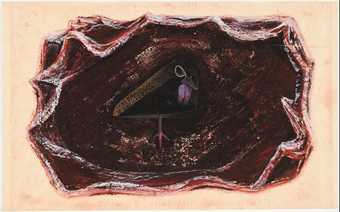

Fig.16

Morris Graves

Little-Known Bird of the Inner Eye 1941

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2019 Morris Graves Foundation

By contrast, in his 21 June 1946 lecture for a BBC television broadcast, Walker’s history of American painting attempted to bridge art and literature as fitting expressions of American exceptionalism (the idea that the United States follows a path shaped by a purpose and norms different from those governing other countries).64 His unusual categorisation confirms the flexibility of the American canon during this period. To Walker, there were three ‘streams’ of American aesthetics: the realistic, the imaginative and the bridging of the two in the naïve.65 Following many of the same artists as Rothenstein, Walker employed novelist Mark Twain to explicate George Bingham’s Raftsmen Playing Cards 1845 and Fur Traders Descending the Missouri c.1845 (both Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and Homer’s Breezing Up (A Fair Wind) 1873–6 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.); paired short stories by Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville with Ryder’s romanticised paintings; juxtaposed novels about New York City by Henry James and Edith Wharton with Cassatt’s Parisian portraits of women; framed T.S. Eliot’s poem ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ (1915) with Meditation by the Sea, a painting from the early 1860s by an unknown artist (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and contextualised Sinclair Lewis’s satirical novel Main Street (1920) with Edward Hopper’s American scene paintings.66 Of contemporary painting, Walker chose to focus his attention on Morris Graves’s Little-Known Bird of the Inner Eye 1941 (fig.16) concluding for viewers that the painting ‘may baffle you, for the artist seems to have had in mind a fossilized impression of a bird … to be found in the West.’67 By comparing words with artworks, Walker attempted to bridge these dual manifestations to evoke the imagined community of American cultural nationalism.

The exhibition’s reception in Britain and America

When examining the diplomatic goals of exhibition, it is important to reconcile these aims with how the journalists interpreted the exhibition in the popular media. Two press releases, dated 11 March 1945 and 1 May 1945, detailed the ambitions of the exhibition to the interested press.68 At least twenty-eight articles in Britain and thirteen articles in the United States explained, praised or criticised the exhibition.69 Most of the British articles provided an overview of the exhibition to their readers without any subsequent analysis of its merits.70 The Yorkshire Press and Leeds Mercury noted the display’s significance, describing it as ‘an exhibition of American paintings, larger and more representative than ever seen before either in the States or here’.71 In a not unexpected attempt to generate readers’ interest, John Redfern listed the value of the collection (£600,000) in order to define the exhibition’s worth in economic terms and therefore to draw visitors.72

The Times reinterpreted the histories of American painting generated separately by Rothenstein and Walker. Of particular importance was the Times’s analysis of the Federal Art Project on American painting:

At once the American painter was free to paint what interested him in his own surroundings, and he was deliberately encouraged to do so with the object of making his work of interest to a larger section of the public than those who could afford to collect works of art. When the federal art project came to an end the artist had discovered the American scene, and many more Americans than before had discovered the artist … But variety means freedom, and there can be little doubt that the American climate is now favorable to an indigenous art.73

This was a much more positive appraisal of American art than that expressed by British critics Anthony Thwaites and Cyril Connolly. In the Magazine of Art, Thwaites argued that the exhibition was confused, suggesting that ‘your committee was influenced by political considerations, so that the modern section became a grab bag of everyone who could pull a string’.74 Without supporting his claim, Thwaites’s critique put into question the motivations behind canon formation. The NGA selection process was influenced by others, specifically Rothenstein, but there is no evidence of a political agency intervening in the process. Nevertheless, as suggested by the selections of Barr and Phillips, most museums chose to emphasise a particular aspect of American art that flavoured the overall history on view. For the syndicated press, Connolly broke the history of American painting into four acts in his article ‘An American Tragedy’. Concluding in the final act that in the early twentieth century,

shattered by sixty years of quantitative Philistinism [in] … American Art … Guilty millionaires flock to endow Galleries and scholarships, Newspapers boost American talent, primitives are discovered and collected, The W.P.A. frescoes small Town-Halls and Country Post Offices; every kind of trick and ism flourishes; ignorant but well-nourished armies of artists argue in paint.75

Connolly’s concern over the impact on the arts of wealthy benefactors and federal support, his anguish over the rise of ‘isms’ and his claim that there exists a ‘well-nourished’ army of artists together decry the perceived autonomous role of the artist in the nineteenth century and the lack of a populist audience in the 1940s.

The American press was equally conflicted in its response to the history of American painting generated by the NGA and displayed at the Tate Gallery. Walker and the NGA staff attempted to encourage interest in the exhibition by giving American journalists from the Ladies’ Home Journal, the New York Times and Vogue photostats of the British clippings and the exhibition checklist.76 Hilda Loveman, editor of Newsweek, concluded, ‘Not even Americans have seen an exhibition of American painting as brilliant as the one that opened this week in London’ and quoted Walker’s own response to possible naysayers: ‘if they don’t like this show, then they don’t like American painting’.77 The author of the article ‘In Tomorrow’s World’ in the New York Herald Tribune wrote that:

Unless all signs are misleading, the coming of peace will bring a revival in interest in all the arts. And why is this so? There are many factors that go into the making of this prophecy, but perhaps the most important is that particularly in the United States of America, several million soldiers will be coming home with a new interest in the arts. After the last war it was observed that many American soldiers returned to their homes as connoisseurs, more or less, of Jacobean furniture and a dozen other things.78

The article suggests the new role art played in the lives of Americans, confirming its significance not only to the newspapers but also in the minds of soldiers returning home, and it solidifies the importance of art displays to Americans after the abrupt defunding of the Work Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project.79

The well-known New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell devoted three articles to the exhibition. As well as serving as an overview of the installation, the articles reminded American readers of the two recent exhibitions of American art in Paris and London in 1938 and, consequently, the current trajectory of international display.80 In acknowledging the importance of an international assessment, Jewell quotes the Times in its pronouncement that, ‘As yet there is inevitably some uncertainty in choosing the appropriate language from the many diverse idioms of modern European art … But variety means freedom, and there can be little doubt that the American climate is now favorable to an indigenous art.’81 To Jewell, this essentialist art was contemporary painting. Leila Mechlin’s article ‘In the Art World’ on the invitation of the 1946 exhibition addressed Jewell’s 1939 writing on the question ‘Have We An American Art?’, with Mechlin stating that ‘the answer must be affirmative. Although we have borrowed much from the art of other countries we have remained subtly American – unmistakably so in spirit and in thought – a free people – distinctive.’82 Without providing any details to support her essentialist claims, Mechlin sought to distinguish American from European art. Despite curators’ and diplomats’ desire to internationalise American art, to at least a portion of art critics (as well as artists and patrons) American art needed to remain in the United States during its development.

A hope for a stable future

American Painting: From the Eighteenth Century to Present Day presented the survival of the Western art canon to a public eager to believe in their continued relevance, despite the devastations of war. Complicating this aesthetic narrative was the evolving status of the British and American nations themselves: the rise of the United States as an international power while Britain suffered the impact of its economic destruction. Thus, the American paintings on view both confirmed the diplomatic relationship between the two nations and reaffirmed the former colony’s cultural independence.

Overcoming Tate Gallery staff’s uneven approach to acquiring and displaying American art, the 1946 exhibition had two immediate effects. It enabled the British not only to maintain contact with the United States but also to initiate other exhibitions between the two countries. In 1946 American newspapers recommended sending American Painting elsewhere, with one journalist concluding that it did ‘a very fortunate service to international friendship. I hope that it may also be sent to Asia, Africa, and South America.’83 After learning about the 1946 exhibition, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam all expressed an interest in hosting it after its closure at the Tate Gallery.84 Despite this initial interest, none of the negotiations led to a travelling exhibition in large part because of transportation and installation costs, the pre-existing exhibition contract between the NGA and the Tate Gallery, and the desire of American owners to see the return of their paintings. Nevertheless, the exhibition became a means of fostering communication between the recently opened NGA and the Tate Gallery. Indeed, the NGA showed an interest in hosting a reciprocal display of British art in the United States as well as a possible exhibition of war portraits.85 In 1947, barely a year after the close of the American painting exhibition, Tate Gallery curators decided to organise a small exhibition of watercolours from the Index of American Design.86 More broadly, these early interactions between the Tate Gallery and American museums and collectors raise wider questions about how the British public understood the United States and its artistic production before the well-received American art exhibitions of the 1950s at the Tate Gallery.

American Painting – organised by the National Gallery of Art; supported by other museum administrators in the United States, Britain and France; promoted by government agencies; and hosted by the Tate Gallery – illustrates the complicated international definition of American art in this post-war moment. Employed as diplomatic agents, the artworks further heightened the politicisation of American contemporary art attempted in Three Centuries of American Art in 1938. The paintings on display in London were a phase in politicised art that would be fully articulated by the CIA in the 1950s. Nevertheless, despite curators’ ambitions for the exhibition, despite its inclusion into a larger, still-forming canon of American painting, and despite its politicisation, the choice of works shows that this was foremost an exhibition intended to visualise the trauma of war, the weight of responsibility shared by two nations and the recognition that by historicising the present chaos through the display of previous wars, there was a path to recovery. Perhaps best illustrated in Ben Shahn’s Liberation (fig.9), a painting of children playing in their bombed-out urban neighbourhood, the goal of the exhibition was to articulate the role of art in visually expressing the cultural rupturing of interwar peace, the historicising of violence and the recovery of Western culture at the end of the Second World War. Within the context of this exhibition, Shahn’s painting proposes that the purpose of the Second World War was to create a stable future, one that the First World War could not. Without minimising the impact of the Second World War, American Painting: From the Eighteenth Century to Present Day sought to cast the United States as an ally to Britain and to locate visually a place in which people from both nations could live in sustained peace.