Fig.1

Catalogue of The New American Painting as Shown in Eight European Countries, 1958–1959, Tate Gallery, London 1959

The Tate Gallery returned to the subject of American painting only three years after its 1956 exhibition Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art. It was a bold decision and one that reflected a real admiration for current artistic developments on the other side of the Atlantic. The new show was called The New American Painting as Shown in Eight European Countries, 1958–1959 and was organised by the International Program of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and circulated under the auspices of the museum’s International Council.1 The International Program was founded in 1953 to send MoMA exhibitions around the world, thereby fostering cultural outreach and exchange with other countries. The New American Painting was assembled at the request of European institutions that wanted a major exhibition of abstract expressionist art from the US.2 As with the 1946 and 1956 exhibitions of American art held at the Tate Gallery, the Trustees formally invited the exhibition’s organisers to allow the show to come to London as part of its European tour.3 Thereafter, it returned to New York where it was presented at its originating museum, MoMA. As MoMA’s Director René d’Harnoncourt noted in the catalogue (a reprinted version of the UK catalogue), it was the first time that a full-scale exhibition prepared for circulation outside of the US had also been shown at the museum (fig.1). ‘Even in New York’, he lamented, ‘we have not until now undertaken so comprehensive a survey’ of abstract expressionism in America.4 This large survey of abstract expressionism was the first such show MoMA organised, although it was almost fifteen years after such artists as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning had made their stylistic breakthroughs.5 In effect, the ‘new American painting’ actually was still relatively novel in the eyes of both European and American audiences in the late 1950s.

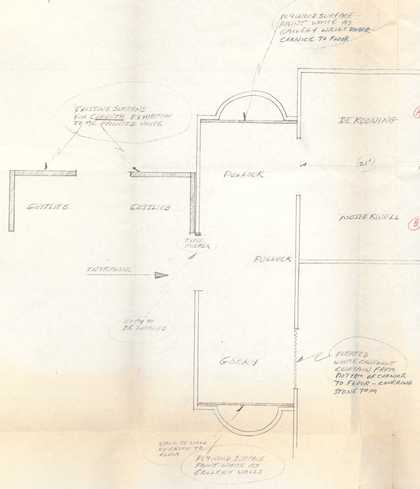

Fig.2

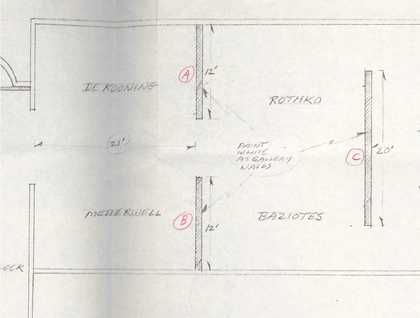

Detail of the floorplan for The New American Painting, 9 February 1959, showing partitions used to divide the space

Exhibition file: New American Painting 1959: Organisation, 21 Mar 1958–25 Mar 1959, Tate Archive TG92/145/1

Fig.3

Detail of the floorplan for The New American Painting, 9 February 1959, showing partitions used to divide the space

Exhibition file: New American Painting 1959: Organisation, 21 Mar 1958–25 Mar 1959, Tate Archive TG92/145/1

Eighty-one paintings by seventeen American artists were selected by MoMA curator Dorothy Miller with assistance from a museum colleague, Frank O’Hara, who was also a poet.6 Porter McCray, Director of the International Program, acted as MoMA’s point of liaison with the Tate Gallery and he installed the exhibition in London.7 McCray also worked closely with Philip James and Gabriel White of the Arts Council in seeing the exhibition to completion. The layout and installation of the show proved to be slightly problematic for the Tate Gallery. The British team had been unaware of the size of MoMA’s proposed exhibition, and when James requested that the Tate Gallery de-install one permanent gallery to make room for the artworks, the Tate Gallery tried to counter this by offering the large central sculpture hall or Duveen Galleries for overflow work.8 White negotiated successfully with McCray/MoMA and the Tate Gallery, ensuring that the additional gallery, rather than the sculpture hall, was cleared and included in the exhibition space to the dismay of the Tate Gallery’s Board of Trustees.9 Galleries 19, 20 and 21 were used for The New American Painting. There were also eight free-standing partitions, all twelve feet high and painted off-white though of varying widths (figs.2–3).

Fig.4

Jackson Pollock

Number 8, 1949 1949

Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York

© 2019 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Jim Frank, Courtesy American Federation of Arts

Fig.5

Mark Rothko

Earth and Green 1954–5

Museum Ludwig, Cologne

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Miller and O’Hara selected a representative range of artists to reflect the origins and breadth of abstract expressionism: William Baziotes, James Brooks, Sam Francis, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Phillip Guston, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Theodoros Stamos, Clyfford Still, Bradley Walker Tomlin and Jack Tworkov. All four Pollocks – a classic drip painting, Number 8, 1949 1949 (fig.4), and three of his later ‘black paintings’, Number 26 1951, Number 27 1951 and Number 12 1952 – were hung in the same gallery along with Gorky’s work. Rothko had five canvases in the show – Number 10 1950 (which also had been in the Tate Gallery’s 1956 exhibition Modern Art in the United States), Number 7 1951, Earth and Green 1954–5 (fig.5), The Black and the White 1956 and Tan and Black on Red 1957 – that were displayed with works by Baziotes.

Fig.6

Hans Namuth

Photograph of Jackson Pollock, 1950

© 1991 Hans Namuth Estate

Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

The exhibition catalogue for The New American Painting was a substantive publication that featured all seventeen artists and their work.10 White wrote the foreword, McCray the preface and Alfred H. Barr Jr, Director of Collections at MoMA, delivered a three-page essay on the history of the New York School, prefacing his text with nine brief quotes by the artists, including Newman, Rothko and Gottlieb. Each painter was given his or her own section that included a portrait photograph, statements written by or about him or her and three illustrations of their works.11 Pollock’s entry featured a photographic portrait by Hans Namuth of the artist seen with a wrinkled brow, a cigarette in hand and wearing a dark T-shirt (fig.6). Visitors to the Parallel of Life and Art exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1953 had seen one of Namuth’s photographs of Pollock in action in his studio. This image, however, depicted him as more pensive and possibly troubled. By contrast, Rudolph Burckhardt’s photograph of Rothko captured the painter in a suit and tie, sitting and smoking.12 Readers who had never seen these men before were presented here with two contrasting impressions – a brooding bohemian versus an intellectual artist.13

On view at the Tate Gallery from 24 February to 22 March 1959, The New American Painting drew a record attendance of 14,718, the highest paying attendance for a comparable period in the history of the Arts Council’s exhibitions at the Tate Gallery.14 The museum aggressively advertised the show by means of Double Crown sized posters in the London underground as well as 960 copies of a three-colour poster sited on London’s streets.15 Considering that attendance had virtually tripled in comparison with the Tate Gallery’s 1956 Modern Art in the United States exhibition, which drew 4,908 visitors, it is clear that abstract expressionism had attracted a buzz in the intervening three years. An ‘Art News Bulletin’, published by the United States Information Service (USIS) at the American Embassy in London, noted in April 1959, ‘The New American Painting exhibition at the Tate Gallery, London, described by Sir John Rothenstein as “remarkable for its uncompromising, outspoken individuality”, drew wide comment in press and radio.’16

Before assessing professional critics’ reactions, however, it might be of interest to report one disgruntled British visitor’s response to the show. A.S. Jarman wrote a letter to the Tate Gallery protesting what he called the ‘misrepresentation’ of the exhibition’s advertised title. ‘All the canvases exhibited’, he observed scathingly, ‘have suffered an application of paint but only a tiny minority can claim to come under the commonly-understood title of “paintings”.’ ‘A vertical black line against a grey background does not come within [the description of a painting]’, he wrote. ‘It remains a vertical black line against a grey background. It also remains an imposter.’17 Jarman also objected to the liquid running of paint on many of the canvases. The Tate Gallery’s spending of public funds ‘to exhibit these examples of American genius’, as he wrote sarcastically, fuelled his anger further.18 The lack of conspicuous content or discernable meaning, coupled with drip, blot or spatter techniques, in many of the works in The New American Painting provoked particular hostility among viewers like Jarman in large part because the works proved challenging to grasp upon first viewing.

Before The New American Painting opened in 1959, the critic and curator Lawrence Alloway had written an essay that was republished by the USIS Cultural Affairs Office in London.19 Alloway sought to debunk myths regarding American painting in Europe. The flow of information about American art through magazines, catalogues and exhibitions in the US had greatly improved since the early 1950s, but Alloway identified several misconceptions that persisted. First, as he stated, ‘Action Painters have since become associated with “the man of action”, such as the Western film hero.’20 Pollock’s reputation typified this conflation of tropes in art and the mass media. Second, the term ‘Action Painting’ evoked ‘the false idea of action rather than the physical presence of the work of art’ for European spectators.21 Similarly, the designation ‘abstract expressionism’ implied that American art was merely self-expression with no other significant content. Alloway believed these terms distracted viewers’ attention away from the properties of coherence and control exhibited by the painters. Pollock and Rothko, he argued, ‘after rejecting conventional notions of finish and design, extended our idea of the control and order possible in a work of art’.22 Alloway’s assertions seemed to reflect Pollock’s own denial that chaos ruled his work.23

The Tate Gallery’s exhibition elicited over thirty reviews in British newspapers and journals. Rothko’s paintings received much more attention from critics in both newspapers and journals than when he had exhibited in Modern Art in the United States in 1956. His works were praised and for most writers seemed a highlight of the exhibition. Critics now accepted the idea that the US had indeed developed its own uniquely American, non-European-derived, style of painting. The Times called this exhibition ‘the finest of its kind we have yet had’, terming it ‘the aesthetic barometer why the United States should so frequently be regarded nowadays as the challenger to, if not actually the inheritor of, the hegemony of Paris in these matters’.24 Echoing Rothenstein’s claims, this London paper saw in the exhibition evidence of an American indigenous style of painting and pioneering sense of individuality: ‘The quality of adventure, of individual striving, of hammering out modes of expression with a pioneering sense of independence, lends these personal utterances a forceful, easily communicable, vitality.’25 Nevile Wallis of the Observer agreed that abstract expressionism was not derivative of European art: Americans ‘have hit on symbols expressive of this age of foreboding, of unnatural forces and discoveries in space’, he wrote, implying perhaps that the United States’ technological and scientific innovations were also uniquely American.26 The works in The New American Painting, he claimed, were ‘clearly attuned to the phenomena of our time’ and had ‘mysterious and universal import’.27

Certain publications addressing disciplines outside of painting, sculpture or art history also published reviews of the exhibition. A critic for the Architects’ Journal deftly found an architectural quality to the works in the exhibition. He suggested that architects should visit the show because the paintings ‘should be seen close together, so that they are the interior, instead of merely decorating it’, and he cited Rothko’s adjacent panels of glowing colour as an example of this ‘new and striking’ effect.28 On the other hand, some reviewers only saw the canvases in The New American Painting as decorative wall textiles, an opinion based on, for instance, Gottlieb’s use of patterns of splotches and stains.29 The Times critic combined these two conflicting observations, stating that the works at the Tate Gallery are ‘perfect mural decorations’ that ‘manage to animate more architectural space than in fact they occupy’.30 Most critics agreed that the impressive size of the canvases was sometimes intimidating.

The Telegraph’s Terence Mullaly, who was certainly negatively affected by the size of the canvases, wrote a scathing review of the show. He was bothered that ‘almost all the pictures in it are as disturbing as they are large’ and objected to the ‘comported masses of paint that vie with the banalities of the catalogue to browbeat us into acceptance’.31 Mullaly believed there was no more to the works than decoration or emotion and suggested that the catalogue essays and artists’ statements were failed attempts to convince viewers there was something substantive at work. Abstract expressionist paintings, he claimed, ‘have no relationship to objective strivings, rather they represent a surrender to the voluptuous and to emotional anarchy’.32 Mullaly’s anarchy metaphor linked action painting to a seemingly tormented, disorderly expression of artistic subjectivity.

The Western Morning News admitted that the size of the works was stereotypically American, quipping that ‘the artists follow their countrymen’s liking for “bigness” as the canvases are huge’.33 The Evening Times (Glasgow) offered viewers a slightly sarcastic recipe for success in following the example set by Americans’ works, ‘Be big, have a statement and then have at it.’34 The London Daily Telegraph went beyond sarcasm to offer an outright hostile assessment: ‘To say it [the new painting] is worse than the old is a ludicrous statement. It is the bottom: we can sink no lower. Hitler died too soon; so did Ruskin.’35 Most of the negative reviews were spurred by discomfort in the face of a radically abstract style, the lack of overt content and the large size of the canvases on view. It is evident that these critics’ inability to move beyond the perceived absence of meaning in Pollock’s paint skeins or Rothko’s rectangles of colour resulted in dismissal of work allegedly deprived of skill, taste, grace or order. Alan Clutton-Brock’s review for the Listener took a different tack, however, praising the visual impact of the canvases and pointed out that ‘the violent slashes of black across white [in a Kline painting] exert something like a spell and seem like magical signs which even if they cannot be interpreted have power over the imagination’.36

Frederick Laws of the Manchester Guardian also offered a favourable review that countered negative criticisms of the size of the works. He suggested that the Americans in the show were confident and aimed to engulf the viewer in their paintings; what made their work good was ‘the scale and reckless assurance of their efforts’.37 Indeed, approbation actually outweighed negative response from British critics. Many, like those quoted above, praised the large size, colourful palette and visual impact of the paintings, acclaiming the Americans’ confidence, vitality, vigour, inventiveness and audacity, as well as the provocative nature of their experiments. However, the response to individual artists, especially Pollock and Rothko, was more mixed and varied from critic to critic.

Pollock was the best-known artist in the show. His untimely death in 1956 had accelerated the propagation of myths surrounding his work both in the US and abroad, and he was viewed unequivocally as the leader of the New York School by American and British critics. A solo show at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, in 1958 had highlighted his importance and in 1960 a photograph of his grave would serve as the introductory plate to the book School of New York: Some Younger Artists, edited by B.H. Friedman and published by Evergreen Books in London.38 At the time of the Tate Gallery’s show, however, it was above all the facture and formal qualities of Pollock’s paintings that were the focus of British critics’ attention.

There was now a palpable shift in critics’ perceptions from a sense of violence in Pollock’s paint skeins three years earlier to a rhetorical musing over the delicacy and beauty of his canvases. The Times complemented Pollock’s and Bradley Walker Tomlin’s ‘tendency to treat surfaces of whatever size as areas to be delicately brought to life; their paintings are elaborate, without focal centres and incline more consciously to beauty or colour and texture.’39 Nevile Wallis was pleased that Pollock’s work in The New American Painting seemed ‘more stimulating than it was in the last section of the American exhibition three years ago’.40 Pollock was also identified frequently as the artist in the show who stood out from the others,41 and one publication labelled his painting Number 12 the outstanding work on view.42

Pollock’s gestural abstractions garnered the lion’s share of praise and ire in the press but Rothko’s colour field canvases also piqued the interest of critics and viewers. An unnamed critic for the London Times placed Rothko’s works at the opposite spectrum from Pollock’s ‘elaborate’ canvases, stating that the former was more inclined to ‘extreme simplicity to achieve complete placidity’.43 Wallis again invoked a technological aesthetic in describing his own experience of viewing Rothko’s paintings, claiming they conveyed a sense of ‘unnaturally luminous fields, tranquil yet ominous after some nuclear convulsion’.44 Wallis, however, was an exception: the majority of critics described Rothko’s work in terms that related to natural elements and the calming effects thereof. Eric Newton of Time and Tide was extremely impressed with Rothko’s work and excluded him from an otherwise negative assessment of the artists in the show. ‘His large areas of gentle colour’, Newton suggested, ‘softened at the edges, are as sensitive as anyone could want: yet they have to be big for one has, as it were, to swim in them – a mild but very delightful experience.’45

Alloway believed that Rothko’s work projected visually into what he called the viewer’s ‘literal participative space’.46 The American’s rectangular bands of yellows, reds and browns appeared to protrude optically forward from the canvas surface, thus occupying not pictorial space but rather the viewer’s space.47 For other critics Rothko’s use of colour appeared masterly. John Russell of the Sunday Times was moved by ‘the absolute tranquility of the great single chords of colour which well out’ from Rothko’s canvases,48 while the Jewish Chronicle dubbed him ‘one of the finest colourists in the exhibition’.49 Dennis Farr in the Burlington Magazine made a valid point when he identified a dichotomy in the exhibition between the tormented frenzy of gestural canvases by Pollock and de Kooning and the ‘idyllic, calm, aquarium-like compositions’ of Rothko, a recognition of increasing differences between the gestural and colour field branches of abstract expressionist art.50 Critics varied in their overall assessment of abstract expressionism after reviewing the exhibition, at times extolling the vigour and energy of the American works and, at others, condemning their alleged lack of harmony, order or beauty. Yet, as Alloway reminded readers and his fellow critics, the New York School was ‘not all one big splash of paint’ but was instead comprised of ‘a varied and complex body of artists with different ideas and performances as any first-rate group can show’.51

This complexity and variety proved to be a double-edged sword for the Americans in the Tate Gallery’s Modern Art in the United States and The New American Painting exhibitions. An artist like Pollock was either praised as a pioneer for his freedom from conventional painting techniques, or he could be accused, as American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler had been a century earlier by British critic John Ruskin, of flinging a pot of paint into the face of the public. Although Britons disagreed on the merits or drawbacks of scale, degree of abstraction, use of colour or lack of apparent content in the New York School works, most recognised that both Modern Art in the United States and The New American Painting provided unique and important opportunities to view a brand new style of work not well known in Britain prior to 1956. It cannot be disputed that these two exhibitions held at the Tate Gallery served the important function of introducing abstract expressionist art into the British artistic and critical milieus. Modern American Art in the United States offered viewers a broad survey of twentieth-century American art as well as a sampling of contemporary developments that had occurred over the previous decade; The New American Painting was a more consolidated showcase of the strongest examples of contemporary American art.