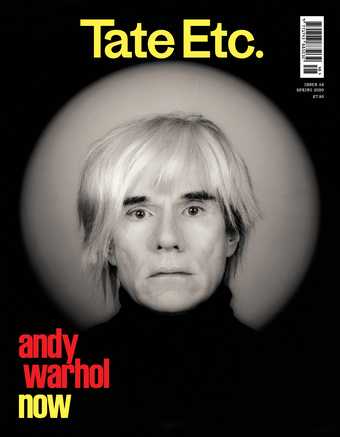

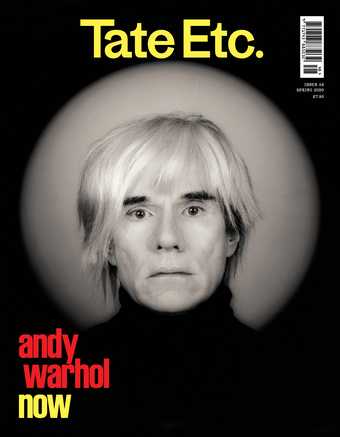

Editor's Note

A bedroom at Andy Warhol's Upper East Side townhouse, 57 East 66th St, New York City, 1987

© Estate of Evelyn Hofer / Getty Images

A colour photograph of a bedroom. In the picture frame, a neoclassical four-poster bed with a brown, frilly pelmet. On a bedside table sits a Tiffany lamp; on the opposite side, a similar table laden with a clutch of bowls brimming with potpourri. Behind this is a small free-standing sculpture of Christ on the cross. Andy Warhol’s personal taste – largely hidden from view until after his death – surprised many: this private side was a world away from the Andy he projected.

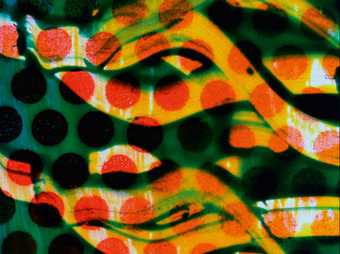

The shy, gay son of immigrants, he would become the hub of New York’s social scene and an American icon who embraced consumerism, celebrity and counterculture – and changed modern art in the process. Popularly radical and radically popular, Warhol was an artist who rearranged the boundaries of art during a period of immense social, political and technological change, as Tate Modern’s exhibition will reveal.

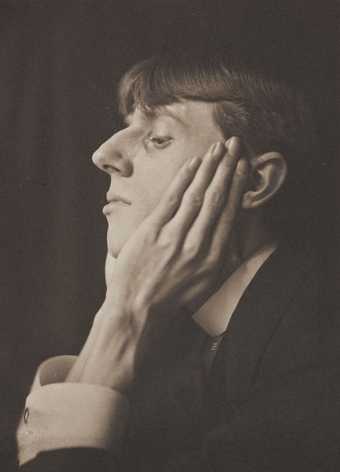

While their art may, at first glance, seem worlds away from each other, Warhol and the English artist Aubrey Beardsley, born just over half a century earlier, shared an ambitious artistic outlook. As Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, the co-curator of Tate Britain’s Beardsley exhibition, writes in these pages: ‘he was as much in control of this elegant, sinuous line, as he was of his image as the enfant terrible of Victorian fin de siècle, relishing controversy’.

One can also imagine that, if they had ever met, they would have shared a few sentiments about their own mortality. Warhol’s attitude to his life and art inexorably shifted after he was shot in 1968. Beardsley was diagnosed with tuberculosis aged seven and knew through most of his life that his time to make an impression would be limited. In both cases, they managed with spectacular success to make their mark in the most extraordinary ways that still resonate with us today.