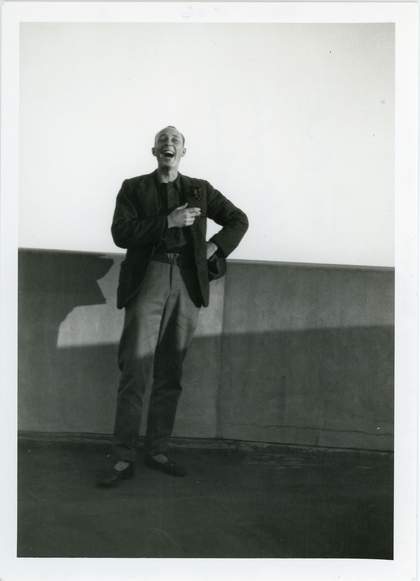

Len Lye in Sydney, c.1925, photographed by Mary Brown

© 2020 The Len Lye Foundation, photo: Mary Brown

‘I thought that you had seen the essential thing as no one had hitherto – I mean you really thought, not of the forms in themselves, but of them as movements in time’. So wrote the critic Roger Fry to Len Lye after seeing one of Lye’s films in 1929, pinpointing, at an early stage in Lye’s career, the essence of his lifelong artistic pursuit: the capture and composition of ‘movements in time’. Lye treasured and preserved Fry’s letter through several relocations, and it can now be found among the Len Lye Foundation Archives at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Zealand.

Len Lye (1901–1980) was a creative polymath: painter, animator, experimental filmmaker, documentary-maker and sculptor. An aficionado of modern music, especially jazz, he was also an enthusiastic researcher, poet, political idealist and ebullient public speaker. He not only worked across many media, but also lived in many countries throughout his life. Born in Christchurch, New Zealand, he grew up in Wellington and Cape Campbell. As a young adult he lived in Sydney and Samoa, before moving to London where he was resident from 1926 until 1944. He then moved to downtown Manhattan in New York where he lived until his death in 1980, also spending time at homes in upstate New York and Puerto Rico from 1971. Consequently, Len Lye is an artist thought of as belonging as much to the Oceanian culture of the South Pacific as to British and American cultures. So ‘movements in time’ is a phrase that could be applied as much to Lye’s changing choice of artistic materials and domestic situation as to the ideas that underpin his work.

Lye’s early attempts to ‘compose’ motion took the form of sketches of various moving objects – people, animals and ocean waves – which led to rudimentary experiments with hand-cranked kinetic sculpture. In Sydney he took a job as an animator with a cinema advertising company and made his first experiments using reject film stock, but it was in England that Lye was able to explore the medium of film most fully. In London, his milieu included artists Ben Nicholson, Betty Muntz and John Piper, and writers Robert Graves and Laura Riding. He created batiks and paintings that were exhibited at the Seven and Five Society, designed book covers and made photograms (such as Self-Planting at Night 1930 – which Lye incorporated into his later self-portrait photogram), as well as having his own writings published, but film was Lye’s primary concern in these years.

Len Lye Still from A Colour Box 1935, 35mm film, colour, 4 min

© 2020 The Len Lye Foundation, courtesy BFI Images

It was with the 1935 film A Colour Box that Lye found the technique for which he is perhaps best known: ‘direct film’, in which the artist paints, scratches or stencils straight onto the film strip. With this technique, Lye produced something new and specific in art (and film). A Colour Box is a joyous, freewheeling convergence of colour, sound and movement that privileged film’s most basic property – ‘movement in time’ – in a way that was not tethered to photographic representation or narrative realism. In the film, a viscous white line surges through fields of iridescent, changing colour; circles and squares swarm diagonally across the screen; multiple, tightly packed lines oscillate like radio waves enacting the trill of the accompanying clarinet.

A key part of the film’s appeal was (and remains) the relationship between the imagery and the music. Lye selected the record ‘La Belle Creole’ by Don Barreto and His Cuban Orchestra and worked with the composer Jack Ellitt (whom he knew from Sydney) to synchronise image and sound in such a way that the energy of both elements served to infuse and increase the other.

Lye described A Colour Box as ‘happy-go-lucky alive stuff for the mind to enjoy’. It was completed with funds from the General Post Office (GPO) and screened publicly in the Granada chain of cinemas owned by Sidney Bernstein, an early champion of Lye’s work. As film curator and historian David Curtis has noted, because the film was shown as part of an ordinary mixed programme in cinemas (including a feature film), A Colour Box is unique in that it was seen ‘by a larger public than any experimental film before it and most since’.

Len Lye Still from Rainbow Dance 1936, 35mm film, Gasparcolor, 4 min

© 2020 The Len Lye Foundation, courtesy BFI Images

Lye further developed his experiments with colour in the 1936 film Rainbow Dance, again produced under the auspices of the GPO. Here Lye made use of the new Gasparcolor process to colourise specially shot live action footage (in a non-realistic style) and then combined it with drawn and stencilled imagery. In the final film, a male figure – the dancer Rupert Doone – engages energetically in various leisure pursuits, all funded (as the film finally reveals) by a Post Office savings account. Lye again worked with Ellitt to synchronise the soundtrack (‘Tony’s Wife’ by Rico’s Creole Band). Despite a warm reception at the 1937 Venice Film Festival, the application of such vibrant colour to ‘real’ images caused Rainbow Dance to be rejected in many UK cinemas as ‘too experimental’. But far from thinking of his exuberant use of film colour as something that might alienate audiences, Lye believed it was precisely colour that was the key to making truly popular film. As he stated in 1935: ‘The main thing that seems to be necessary is to portray in visual imagery the purest pleasure to the audience, who, having retired from reality, have entered a cinema to live in a re-created world where they can have all sorts of adventures, sing all sorts of songs and visit all sorts of places. The sky may be violet, the grass blue, the clouds green, anything, so long as the colour increases the pleasure.’

Lye’s next film, the 1937 Trade Tattoo, took another new direction, though again non-realistic colour plays a prominent role. Trade Tattoo was created using off-cuts (‘found footage’) from films by his fellow directors at the GPO Film Unit, which Lye combined in a montage on Technicolor stock, and overlaid with stencilled and drawn designs to music by the Lecuona Cuban Boys band. Depicting ‘the rhythm of work-a-day Britain’, Trade Tattoo renders firing furnaces in stark neon shades; men are shown at work on ships and docks; city workers and farm workers feature alongside communications imagery in bold colour juxtapositions: trains, telephone exchanges, envelopes and clocks. Lye’s own description of the making of Trade Tattoo matches the restless kinetic energy of the film itself: ‘take an “A” roll of live action and sync it to music – and get it kinaesthetic man. Take a “B” roll of designs and sync that too, allowing for your counterpointing visual effects … what that film has got is, in feeling, a romanticism about the work of the everyday in walk-sit works of life. OK?’

Paramount for Lye was the desire to appeal to a broad audience in film, and so the subject of ‘work-a-day Britain’ was sympathetic to this aspiration, as were many of the other subjects he was commissioned to tackle in the context of the GPO Film Unit and, later, for the British Ministry of Information and the March of Time company in the USA. But, on a more basic level, Lye wanted to create work that would appeal, almost precognitively, to a kinaesthetic sense felt deeply in the body, not the mind. He wanted to make work that was universal, accessible to us all. Lye felt that the kinetic energies in A Colour Box, Rainbow Dance and Trade Tattoo had such an appeal, and in the next phase of his career he strove to compose ‘movements in time’ more plainly, in such a way as to bring about a direct, empathic, bodily response from his audiences. To this end, he produced kinetic sculpture but later also more abstract black and white ‘direct films’, such as Free Radicals 1958 and Particles in Space 1979 – works that were to inspire the next generation of artists and filmmakers to capture and compose motion as Lye had. Summing up his devotion, Lye explained: ‘movement … is not a means or a medium or a thing in itself; it is absolutely nothing or everything.’

A Colour Box, Rainbow Dance and Trade Tattoo are included in the display Len Lye: Film Animations 1935–1937, Tate Britain, until 17 May, curated by Andrew Wilson, Senior Curator, Modern British Art.

Inga Fraser is a curator and writer, and a current collaborative doctoral researcher with Tate and the Royal College of Art.