Graciela Iturbide

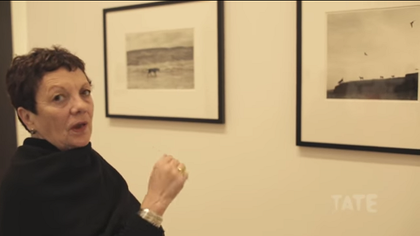

Cholos, White Fence, East Los Angeles 1979

Gelatin silver print on paper

© Graciela Iturbide, courtesy ROSEGALLERY

The Mexican writer Carlos Monsiváis once described the photography of Graciela Iturbide (b1942) as an art of echoes and sediments, capable of relaying the resonances and residues of surrealism, abstraction, documentary realism and ethnography, while forging a deeply personal take on overlooked subjects and forms of life. Her themes are wide-ranging, from the women-led market and bird-ridden cemetery in Juchitán, to the ritual sacrifice and ornamentation of sheep in La Mixteca, to the brides and dancers of Chalma, Tlaxcala and Sonora sharing their traditional attires and their nudity.

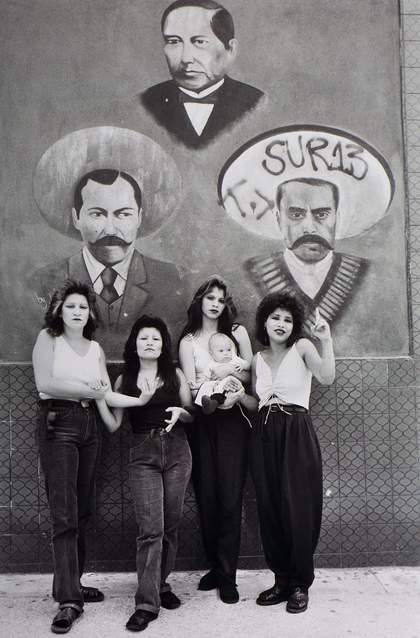

Graciela Iturbide

Autorretrato en Casa de Trotsky 2006

Gelatin silver print on paper

© Graciela Iturbide, courtesy Tate

While Iturbide shies away from creating a sense of hierarchy between ritual and everyday life, her photographs are documentation and lyricism entwined. They entice the viewer with an intimate and complicit gaze that addresses the lives of indigenous communities without craving for a sense of authenticity. Her photographs are not just depictions of the cultural hybridity that has resulted from colonialism and modernisation; they are sensuous and playful enactments of these histories.

Graciela Iturbide

Casa de Frida Kahlo, Coyocan, Mexico 2005

Dye transfer print on paper

© Graciela Iturbide, courtesy Wilson Centre for Photography

An early apprenticeship under modernist photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo (1902–2002), followed by a lifelong friendship, persuaded Iturbide of the unparalleled expressive potency of photography’s stillness: its capacity to not sculpt time (as in the case of cinema) but to suspend it. As Iturbide recalls, she not only travelled throughout Mexico with Álvarez Bravo in the early 1970s, she also learnt to experience the country ‘through his eyes’. Much of her own subsequent work can be seen as both a return to, and a departure from, his vision.

Iturbide’s movement beyond previous photographic traditions is vividly seen in her Juchitán series from the 1980s, where she portrays Zapotec communities without any felt desire to illustrate or allegorise: here one does not encounter groups representative of anything; instead one confronts individuals, in all their vulnerability and singularity, despite the many traditions they inhabit.

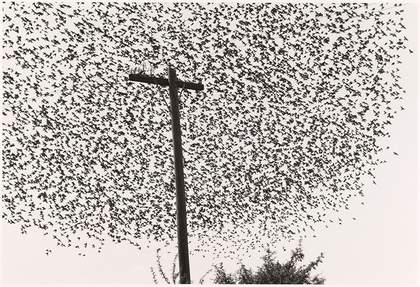

Graciela Iturbide

Birds on the Pole, Guanajuato, Mexico 1990

Gelatin silver print on paper

© Graciela Iturbide, courtesy Tate

Interweaving her own way of seeing with those of the subjects depicted, Iturbide also recognises an inconsolable abyss. We can see this most strikingly in a long series on birds that she developed in Mexico and India over many years, in which she dwells on the lives and afterlives of our winged companions, who are also, at times, enigmatic others – a divide entrenched in the Christian Trinity, where the godly assumes both avian and human form. As author Bruce Wagner has written in response to Iturbide’s photographs: ‘The birds are birds as we know them and are birds that cannot be known … the birds are dirty and transient and religious and encaged within effigies of themselves’.

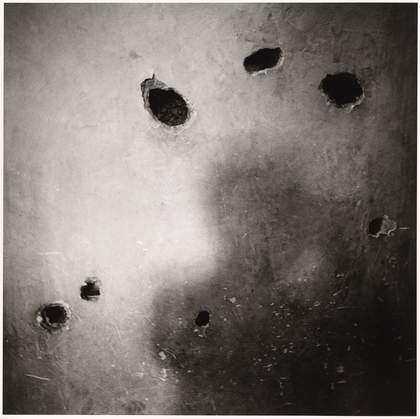

Graciela Iturbide

Sin Titulo, White Fence, East LA 1990

Gelatin silver print on paper

© Graciela Iturbide, courtesy ROSEGALLERY

Iturbide’s embrace of unknowability also permeates her cautious unveiling of Frida Kahlo’s prosthetic and personal objects, which had been concealed in the painter’s bathroom for half a decade. In these solemn images, traces of pain become markers of an impossible proximity. Similarly, the photographer espouses ambiguity over transparency when she casts her own shadow on a bullet-ridden wall in Leon Trotsky’s house and thus turns the forensic scene into an enigmatic self-portrait.

Graciela Iturbide

Mercado de Sonora, Mexico City 1978

Gelatin silver print on paper

© Graciela Iturbide, courtesy Tate

In the 1980s, Iturbide travelled to Los Angeles to photograph the marginalised communities of cholos living in the Eastside, capturing their nostalgia for a Mexico construed through residues of mythology. In one of the images, four women, one carrying a baby, stand below a mural of historical figures: Benito Juárez, the forbearer of the secular republic, appears above the revolutionary leaders Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. Iturbide recalls how the cholas mistook the men in the mural for mariachis, and requested that she take a shot. In the photograph, the four cholas complement and stand before this all-male line-up of official heroes. Wearing their typical baggy pants and white tops as they link arms to create a single form, these women embody the Mexican nation outside its recognised borders. Like so many of Iturbide’s photographs, it is an image permeated by the instability of identity: both collective and singularising, both migratory and evocative of our roots.

A display of photographs by Graciela Iturbide curated by Yasufumi Nakamori, Senior Curator, International Art (Photography), is at Tate Modern. This display comprises Tate collection photographs presented by Michael and Jane Wilson (Tate Americas Foundation) 2017, and additional loans from the collection of the Wilson Centre for Photography.

Mara Polgovsky is a Lecturer in Contemporary Art at Birkbeck, University of London.

Author’s note: The term cholos or cholas is used informally in parts of the United States to refer to people of Latin American descent, usually Mexican, associated with urban subcultures. While some perceive it as derogatory, it has also been historically appropriated by migrant communities.