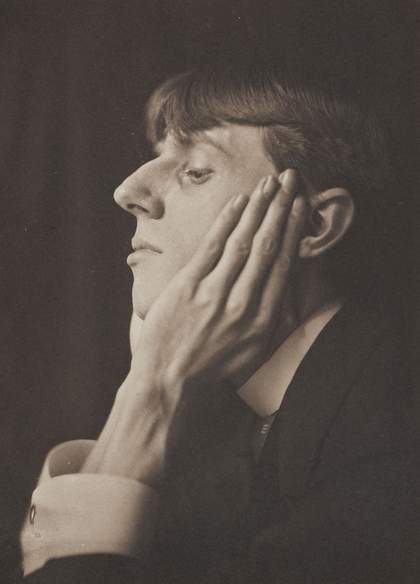

Frederick Evans

Portrait of Aubrey Beardsley 1893

Platinum print

Wilson Centre for Photography

‘While every connoisseur declared that line [of Aubrey Beardsley] superb, there were others who deplored that he did not know where to draw it’, wrote the novelist Ada Leverson.

One might also add that he was as much in control of this elegant, sinuous line, as he was of his image as the enfant terrible of Victorian fin de siècle, relishing controversy. Aubrey Beardsley was born in Brighton in 1872. He and his elder sister Mabel were brought up by their formidable mother, Ellen (née Pitt), in the profound conviction that they would accomplish great things. When diagnosed with tuberculosis aged seven, Beardsley also knew that his time to make an impression would be limited. He excelled at piano, and while he took great pleasure in caricaturing schoolmates and teachers alike, he also gained popularity at Brighton Grammar School as a writer. Literature, which he devoured, was his first calling and would also play a central part in his art.

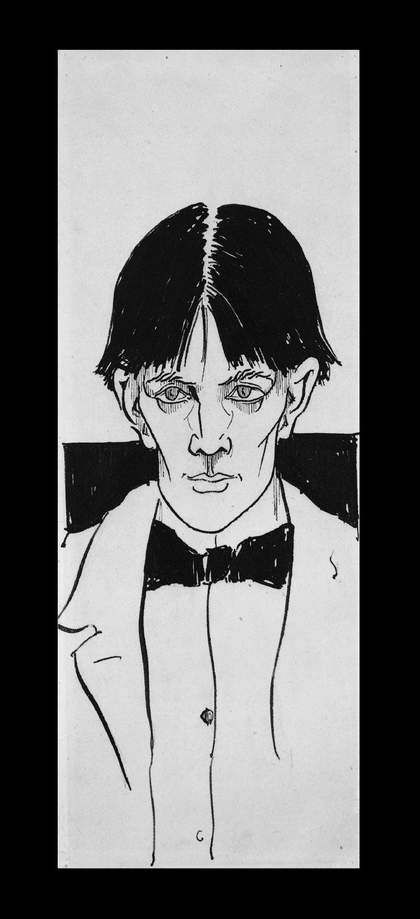

Beardsley’s mother was the daughter of a retired surgeon major in the East India Company and had social aspirations. Beardsley’s father, Vincent, was of independent means when they married, but a clergyman’s widow threatened to sue him for breaking their engagement. He settled out of court to avoid a scandal, which meant selling property, renting only modest lodgings in London, and taking a job. Ellen gave piano lessons to make ends meet, and when Aubrey finished school, he too had to take a job as a clerk to help support his family. His thwarted artistic ambitions would find expression in his drawing Le Dèbris d’un Poète (The Remains of a Poet) 1892, which depicts a young man sitting at a clerk’s desk. Still, Beardsley indulged his insatiable thirst for literature in London bookshops during his lunch breaks, and he drew late into the night when his health permitted. In 1891, an encounter with his then-idol Edward Burne-Jones comforted him in the belief that he should focus on art: ‘I seldom or never advise anyone to take up art as a profession, but in your case I can do nothing else’. Beardsley started attending evening classes at the Westminster School of Art, under Fred Brown.

Aubrey Beardsley

Le Dèbris d’un poète c1892

Ink and wash on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

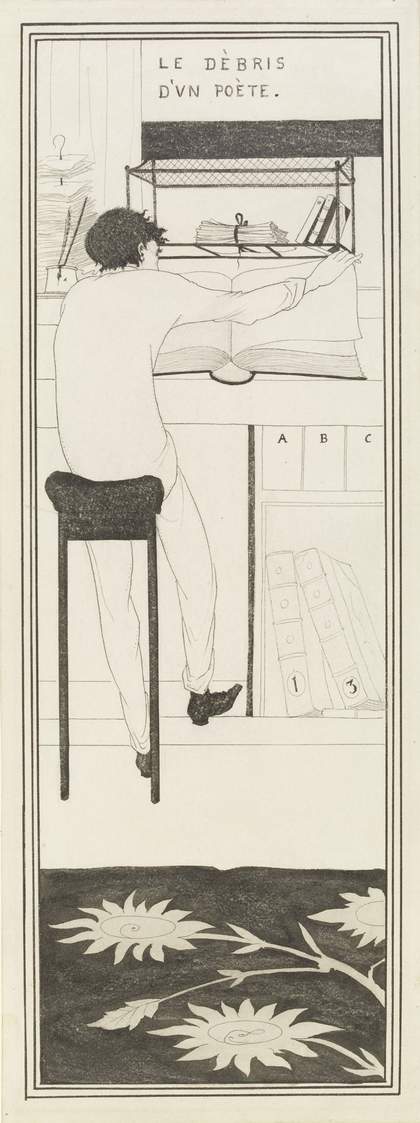

Beardsley’s first major commission, Le Morte Darthur 1893–4, for J.M. Dent, revealed his debt to his Pre-Raphaelite mentor, but also his own striking originality. It occupied him between the end of 1892 and the end of 1894, during which time, the income from the 353 drawings that he produced enabled him to give up his clerkship. Characteristically, Beardsley often went ‘off-brief’, introducing satyrs, mermaids, caricatures, and the odd concealed phallus in his most intricate drawings, partly to avoid boredom, partly because of his boundless imaginative powers. Recognition swiftly followed with an article accompanied by four of his new ‘japonesque’ drawings in the first issue of The Studio, published in April 1893. Notoriety also ensued with the ‘weird … morbid attractiveness’ of his illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s Salome (originally drawn in 1893), and his famous contributions to literary periodical The Yellow Book, which came to define the 1890s, also dubbed the ‘Beardsley period’. He was sacked before the fifth volume of the periodical was out, a victim of Wilde’s downfall. Wit, dandyism and a subversive spirit had become hazardous currencies. Beardsley was forced to sell the house that he had bought with Mabel in Pimlico, and he spent more and more time in Dieppe and Paris.

Aubrey Beardsley

The Slippers of Cinderella 1894

Ink and watercolour on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press

Beardsley’s health was deteriorating steadily, but his inventiveness and range of styles did not abate. He was one of a kind, and there is a timeless aspect to his art. As the German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe noted, ‘in one day he could be Baroque, Empire, Pre-Raphaelite or Japanese. Yet he was always Beardsley.’ He went on to develop what he jokingly called an “embroidered”, rococo style for his illustrations to Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1712) and The Savoy magazine, while adopting an austere purity of line in his most explicit drawings for an 1896 edition of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata, all produced for his new publisher, the likeable but morally questionable Leonard Smithers. Beardsley was almost solely reliant on the undependable Smithers for income, and on the generosity of his new friend, Marc-André Raffalovich, a wealthy poet and theorist of homosexuality. Raffalovich supported the artist for the last 18 months of his life, and encouraged him to convert to Catholicism, just as he himself had done under the influence of his lifelong partner, John Gray, Wilde’s former lover. Beardsley died in Menton in the south of France in 1898, aged 25, having gained international fame. Just before he passed, he begged Smithers to destroy his ‘obscene’ pictures, which, thankfully, he failed to do. Few knew of the existence of such drawings then, but they have since perfected his portrait as the witty, provocative wunderkind of decadence.

Aubrey Beardsley, Tate Britain, 4 March – 25 May, curated by Stephen Calloway and Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Curator British Art, 1850–1915 with Alice Insley, Assistant Curator, Historic British Art. Supported by the Aubrey Beardsley Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation and Tate Members. Organised by Tate Britain in collaboration with the Museé d’Orsay, Paris.

Writer and artist Audrey Niffenegger remembers seeing Beardsley’s drawings up-close and personal

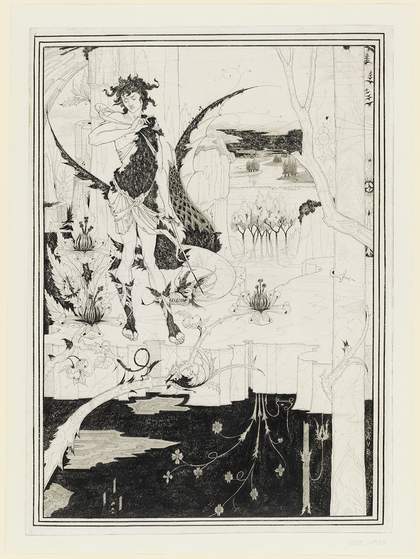

Aubrey Beardsley

Siegfried, Act II 1892–3

Ink and wash on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

A few years ago I found myself standing next to Aubrey Beardsley’s desk. It was in the Dulwich Picture Gallery and I was not expecting to encounter it; I didn’t know any such article of furniture still existed. I’ve never been particularly attracted to the relics of saints, but I wanted to touch Beardsley’s desk. I didn’t expect miraculous cures or communion with the dead, but I had a sudden desire to touch this modest table where he’d spent so many hours of his short life, this horizontal wooden surface that had held his drawings as they came into being.

I have held some of those drawings in my hands. They reside in acid-free mats, in special boxes, in the collections of great museums. The original drawings are more delicate than old reproductions can capture and the photo-engravers must have sometimes despaired. Looking at the drawings you sense the power, control and restraint of Beardsley’s hand. His famous line is more varied, more subtle in the actual drawings. I am familiar with the shock he must have felt every time he saw what the platemakers had made of his work, and yet his sensibility was perfect for the reproductive technology of his time.

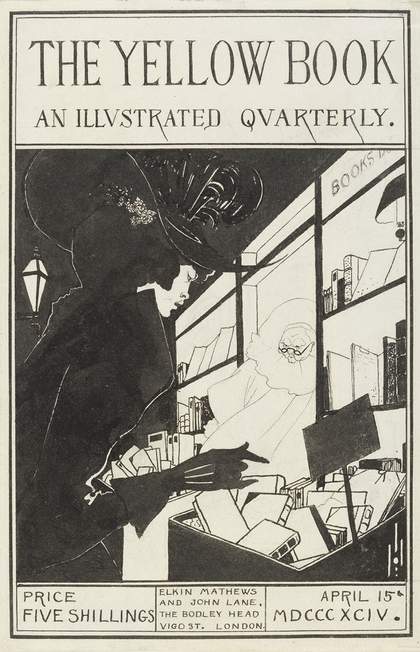

Design for the front cover of the prospectus of Aubrey Beardsley’s The Yellow Book, Volume I, 1894, ink and wash on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

Beardsley was a writer’s artist and many of his images are literary, meant to be seen by readers. One of his best drawings is the design for the prospectus of The Yellow Book: a woman stands in front of a bookshop at night, perusing a jumbled pile of books while the bookseller regards her sceptically. She is wearing black and seems to emerge from the night, her gloved hand hovering like a hungry crow, uncertain but poised to make a selection. That hand will hesitate forever – the union of reader and book will never be achieved – yet it reminds us of that perfect, agonising pleasure before the choice is made.

The artist sits and draws; the reader selects her book; the viewer in the gallery stands amid the drawings, made so many years before at this very table. His hand, her hand, my hand: I look around, already guilty; no one is watching. Beardsley’s art is all about desire and I can choose to leave this small transgression unconsummated, hovering; in the end, all that matters is the art he made, to which I am always returning.

Audrey Niffenegger is a writer, artist and academic who lives in Chicago. She is currently working on a sequel to her bestselling novel The Time Traveler’s Wife (2003).

Writer Michael Bracewell celebrates the weirdness of Beardsley

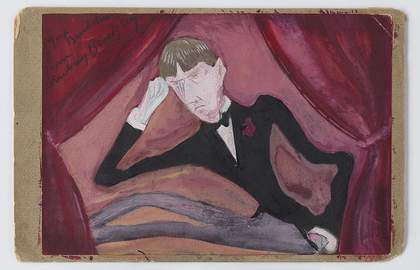

Aubrey Beardsley

Self-Caricature 1894

Ink and wash over photograph

Courtesy Barry Humphries, photo: Prudence Cuming Ltd.

Aubrey Beardsley has been in my life since around 1972, when I was 14 years old. This meant that I was too young to have retained anything save the mistiest impressions of the great Beardsley retrospective exhibition held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1966.

This was, famously, the show that triggered Beardsley’s uptake into the mainstream of psychedelic pop styling; but, for me, Beardsley – who died tragically but glamorously young at the age of 25 in 1898 – is without question, as regards the wanderings of his spirit at any rate, a child of the 1970s. How can a young man whose face was likened by Oscar Wilde to ‘a silver hatchet’ be allotted any period other than the early 1970s to haunt and bewitch and make himself at home in?

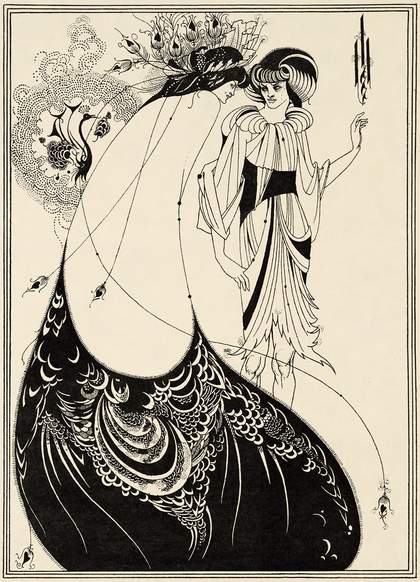

Quite literally, in fact: for every bed-sitting room from sunny South Kensington outwards had a Beardsley poster – The Climax 1893, Isolde 1895 and The Peacock Skirt 1893 were favourites – and Beardsley posters appear in both Thames Television’s The Sweeney (season one aired in 1975) and BBC’s hit TV series, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy shown in 1979.

Famously lampooned by Punch magazine as ‘Awfully Weirdly’, a great pop name, it was Beardsley’s very weirdness – the eternal neurotic boy outsider art student from Brighton, coldly, sexually ambiguous, tortured by pornographic thoughts, a stylist of genius and almost more of a symbol of decadence than Wilde himself – that made him such a poster boy for the early to mid 1970s; that period when a guitarist could call himself Ariel Bender, and Bowie could have a glam-stomper hit ‘subconsciously inspired’ by Jean Genet.

In the early summer of 1974, having heard that Beardsley once stayed at the Spread Eagle Hotel in Epsom, Surrey, a friend and I sought the place out and lounged around outside it smoking Saint Moritz cigarettes and trying to look awfully weird. Apparently our hero wrote a letter from there to Leonard Smithers, publisher and pornographer, so we felt we had no choice.

Michael Bracewell is a writer based in West Sussex.

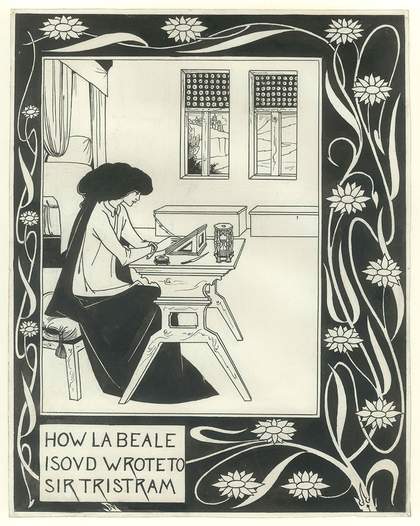

Art historian Simon Wilson on Beardsley’s drawing How La Beale Isoud Wrote to Sir Tristram 1893

Aubrey Beardsley

ow la Beale Isoud Wrote to Sir Tristram c.1893

Ink on paper

Alessandra and Simon Wilson

I discovered Aubrey Beardsley as a student in the early 1960s. Then I found the passage about him in DH Lawrence’s first novel The White Peacock (1911): ‘I sat and looked and my soul leaped out upon the new thing.’ My response exactly. Decades later I was able to acquire a drawing by him. I chose this one not least because the figure uncannily resembled my then recently late wife. As she was, the woman Beardsley depicts is both intellectual and amorous. As well as slightly androgynous. The drawing is for an 1893–94 edition of the first English version of the Arthurian legends, Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur (1485). Thanks to Beardsley, it is a masterpiece of book illustration.

Beardsley made 353 drawings for the book, mostly initial letters and small pictures for chapter headings. This is one of the 15 individual full-page illustrations he made. Of these, Beardsley devoted four to the story of Sir Tristram and La Beale Isoud, although it is only one of nine major narratives in the book. It is of course one of the world’s great love stories, but in it also is focused the extraordinary combination of violence and licentiousness that Malory reveals at the heart of the court of King Arthur.

Isoud is seen here in the castle of her husband King Mark, where she had previously been conducting a torrid secret affair with Tristram. He has been discovered and forced to flee. Hearing that Tristram has himself married, she writes begging him to come back to her. He does and is secreted in a chamber in the castle, and, as Malory says, ‘the joys that were betwixt [them] there is no tongue can tell it’. Beardsley has subtly recognised the powerful sexual impulse underlying what she is writing by the clearly phallic form of the bed end and the almost equally suggestive form of the bed drape hanging above it, as well as by the prominent presence of the bed itself, which, incidentally, Beardsley has clearly lifted from the Van Eyck Arnolfini Portrait 1434, already in the National Gallery in his time. This has not to my knowledge been previously noted.

Simon Wilson is an art historian and former curator at Tate. His book Beardsley (1983) was published by Phaidon Press, and in 1998 he co-curated the exhibition Aubrey Beardsley: A Centenary Tribute at three museums in Japan.

Alex Pilcher sees more than black and white in Beardsley’s The Dancer’s Reward 1893

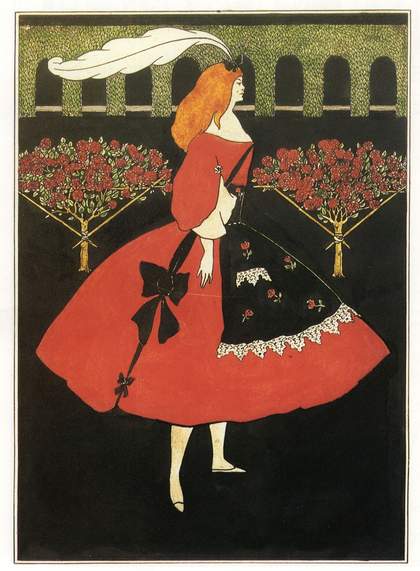

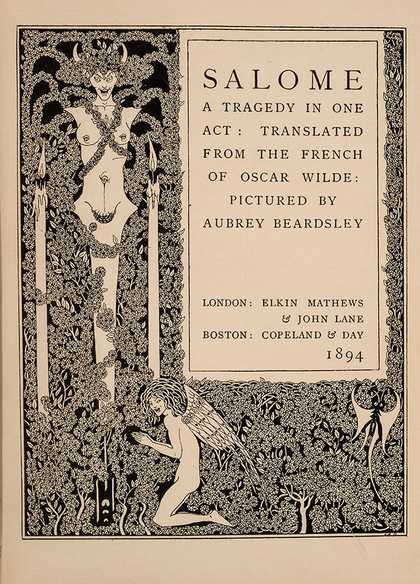

Title page from Salome published by Mathews and Lane in 1894

Private collection

In Oscar Wilde’s one-act Salome (1891/1894) – forever linked with Aubrey Beardsley after his drawings embellished the play’s first English edition – the action is propelled to its grisly denouement by a chain of aesthetic fixations. Amid the febrile yearning, jailed prophet Jokanaan marks a calamitous anomaly, unmoved as Salome speaks her desire in heady, clustering similes, likening Jokanaan’s wan flesh to ivory, silver, moonbeams, lilies, snow and roses – until she blurts: ‘There is nothing in the world so white as thy body.’ Wilde’s moonlit characters dote on whiteness and white things, an incongruous verbal tic for a drama set in ancient Judaea. Yet recall how, as Salome was penned, Europeans pushed imperial conquest to its limit. White supremacy, theorised as racial destiny, now permeated state policy. Does that same collective narcissism colour Wilde’s text?

Beardsley’s sparingly inked characters, truly lily white, might seem apt for such a context. But this artist’s black-andwhite world is no advertisement for imperial Britain’s racialised self-regard. Those unruly physiques that prance and pose through Beardsley’s output subvert Victorians’ presiding aesthetic chauvinism. Scouting for models, his Salome drawings snub classical Greece for Japan. The stylised mouths in The Dancer’s Reward bow to ukiyo-e woodcut prints. A fondness for swirling turrets of fabric, excused from limp obedience to a wearer’s anatomy, was lifted from the same source.

Aubrey Beardsley The Dancer’s Reward 1893, (reproduced here from a line block print published in 1907), line block print on paper, 22.5 × 16.2 cm

Courtesy Stephen Calloway

Beardsley’s ebullient imagination, so often refreshingly inclusive, still flags in the face of ethnic variation. Types take over. His Jews share the same hooked nose. Fleshy-lipped figures in outsized turbans leer in sinister cameo roles. Rendered in the signature high-contrast style, even such racial others emerge ivory pale. Among surviving drawings, only twice does Beardsley acknowledge melanin. And in The Dancer’s Reward, Naaman – Herod’s enslaved executioner – is often overlooked. Beardsley has observed Wilde’s stage direction: ‘A huge black arm … comes forth from the cistern, bearing on a silver shield the head of Jokanaan.’ Critics have applauded the visual slippage from elongated limb to table support.

Clothing racial servitude in biblical garb was a longstanding sleight of history honed by European artists (one early adopter is Beardsley’s beloved Andrea Mantegna). Naaman does not meekly wait palace tables however, but slays one whose whiteness is beyond compare – and at a white woman’s behest. Reversing the drift of its era’s racist violence, Salome offered white audiences a frisson of speculative terror. Perhaps this explains why, once Naaman descends to carry out the order, only his arm makes re-entry. The threat of Wilde’s ‘huge Negro’ returning, bloody sword in hand, is averted and, in our final glimpse, Naaman is reduced, literally, to a prop.

Alex Pilcher is Senior Web Developer at Tate and the author of A Queer Little History of Art (2017) and Love (2019), both published by Tate Publishing.

Artist Linder recalls the moment she fell under Beardsley’s glamorous spell

Aubrey Beardsley

The Peacock Skirt 1893, (reproduced here from a line block print published in 1907)

Line block print on paper

Courtesy Stephen Calloway

In my teenage years in the late 1960s, posters on bedroom walls were all the rage and Beardsley’s The Peacock Skirt 1893 took pride of place above my bed. In 1970, as a 16-year-old, I made my first ever trip from Wigan to London. I went straight to the Victoria and Albert Museum to look at Beardsley drawings as part of my research for an art history essay. I had made an appointment in advance at the V&A, and when I arrived at the archive they handed me a large box labelled: ‘Aubrey Beardsley’. I was thrilled. The drawings were far smaller than I had imagined. Hours passed by as my teenage psyche took in every detail of Beardsley’s image making.

After I finished, I walked to the Biba shop nearby and bought some black lipstick, then dashed to catch the train north. Looking back, half a century later, it seems so dreamlike, but I can now say with certainty that those hours of Beardsley and Biba left their mark. The day became a rite of passage of sorts. From that mining village in the north to the shrine of ‘Awfully Weirdly’ (as Beardsley was dubbed) at the V&A… nothing ever seemed quite the same again.

Both coal and Indian ink are the deepest of black. Beardsley’s line had an economy of means, and heaven knows that’s how we all lived then. There wasn’t any hint of decadence emanating from the coal mines, but Beardsley’s art opened my eyes to another world, beyond that of natural light, to another sort of underground besides the pit.

I became obsessed with creating the same unwavering line as Beardsley. I coveted the 0.3 Rotring Rapidograph pen of my art teacher, because I knew that it would liberate me. I eventually shoplifted one. Several years later, in 1976, I exchanged the pen for a surgeon’s scalpel in order to make new works for new times. The cuts that I made then, and now, have all the precision of the Rapidograph, inspired by the fluidity of Beardsley’s pen.

When I look at Beardsley’s art now, I can still slip under his enchantment. And I can’t forget that delight upon opening the box of drawings and seeing Beardsley’s work for the first time, no longer in reproduction, no longer confined by the pages of a book. As I held his drawings in my hands and marvelled, the transmission of glamour was direct and long-lasting. Black Biba lipstick sealed the spell.

Linder is an artist who lives and works in London. A retrospective exhibition of her work opens at Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge on 14 February.