In 1920, amid the fervour of post-revolutionary Russia, Naum Gabo (1890–1977) and his brother Antoine Pevsner launched the Realistic Manifesto on the streets of Moscow. The radical document that they pasted on hoardings across the city proclaimed the need for art to connect with the modern age, and set forth a number of principles, including the assertion that ‘kinetic rhythms’ were the ‘basic form of our perception of real time…’ Gabo decreed that space and time should be implicit to new forms of art as the ‘only forms on which life is built and hence art must be constructed...’

Gabo explored these progressive ideas on rhythm, movement, time and space through architectural designs, paintings and sculptures, and stage and costume design, as well as works in various media that reflected his interest in film and music. One such key work is Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave) 1919–20, a mechanised rod that Gabo created to demonstrate the perception of a volume in space (and which sets the scene for the exhibition at Tate St Ives). It highlights Gabo’s longheld fascination with kinesis, the revelation of innate structural forces beyond solid mass, and the viewer’s participation in the activation of forms in his art.

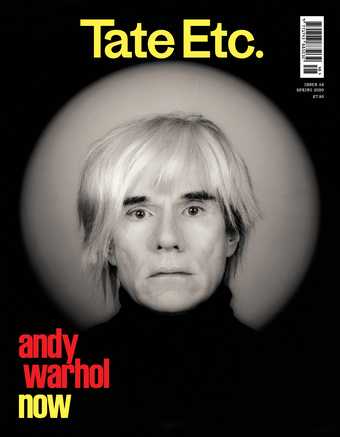

Naum Gabo with Head No.2 1916 outside Tate Britain in 1964

The Work of Naum Gabo © Nina & Graham Williams / Tate, 2020, courtesy Tate Library and Archive

Photographs and surviving drawings show his innovative architectural designs, which reflect his interest in these themes – as seen in his designs for the Palace of the Soviets 1931–1933, as well as Sketch for a Tower with Airplane Landing Pad c1924, and Sketch for a Flying Machine (Whizstarter) c1920s.

Several of these designs introduced the elements of movement and transparency within architecture; Gabo would demonstrate this ‘dematerialisation’ or dissolving of the surfaces of form in some of his finest sculptural works that incorporate glass or plastic as a material, including Column 1921–2 (made from glass, Perspex and stainless steel), and Linear Construction No. 1 1942–3 (made with Perspex and nylon).

As many of his works suggest, Gabo had a deep connection with organic and natural forms, particularly those made from the mid-1930s onwards, such as Construction: Stone with a Collar 1933/c1936–7, Kinetic Stone Carving 1936–44 (created from a single block of Portland stone), and Construction in Space with Crystalline Centre 1938–40. The elegant Linear Construction No. 2 1970–1, made from light-catching nylon filament wound around two intersecting plastic planes, was developed from Gabo’s unrealised project for the lobby of the Esso Building in New York in the late 1940s.

Naum Gabo’s Linear Construction No.4 installed at the Nationalgalerie Berlin in 1971

ullstein bild / Getty Images

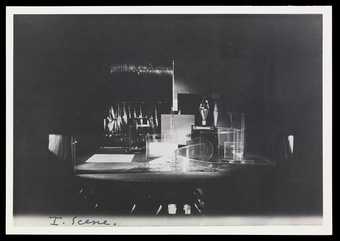

In addition to organic components, transparency was also a key element in Gabo’s artworks, including the set and costume designs he made for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes performance of La Chatte (1927). Here, the abstract plastic forms and metal planes created a highly reflective environment in which dancers performed, adorned with plastic elements (such as a helmet or headdress) that extended their movements into space. Gabo’s Constructivist Ballet, a toy created for his daughter Nina during the Second World War, shows a more playful approach to the subject of ballet: a ‘stage’ under a plastic semi-spherical dome is populated by tiny figures and objects activated by static electricity.

Barbara Hepworth, Naum Gabo, Henry Moore and Margaret Read with Naum Gabo’s sculpture Linear Construction No. 2 at Tate Gallery, London in 1970

Photo by Douglas Miller / Keystone / Getty Images

Gabo’s interest in music was important to him; he regarded it as the most ‘absolute and abstract of the arts’. His ethereal series of images generated from the 1950s–70s in the evolving Opus suite of monoprints, as well as sculptural works such as Linear Construction No. 1 1942–3 that was likened to a ‘heavenly instrument’, showed his further exploration of the notion of rhythm that is inherent to music and poetry.

While Gabo is remembered as an historic figure, his legacy is considerable, spanning the fields of art, architecture and design. His work was of great interest to architects, including Richard Rogers and Norman Foster, both of whom knew Gabo and debated his architectural practice through extended visits and conversations – Foster’s postgraduate paper on the Palace of the Soviets is testament to his importance. He also influenced a generation of post-war artists – from the Dvizhenie group in the USSR, to George Rickey and Wen-Ying Tsai in the United States, to artists such as Barbara Kasten today. In our current era of instant communication and the reign of time-based media, this exhibition presents Gabo’s work afresh to new audiences, affirming his role as a visionary artist whose work was very much of, but also ahead of, his time.

Naum Gabo, Tate St Ives, 25 January – 3 May 2020, curated by Anne Barlow, Director, Tate St Ives, Sara Matson, Exhibition and Displays Curator, Tate St Ives, and Natalia Sidlina, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern.

Anne Barlow is Director of Tate St Ives.

Barbara Kasten on Naum Gabo

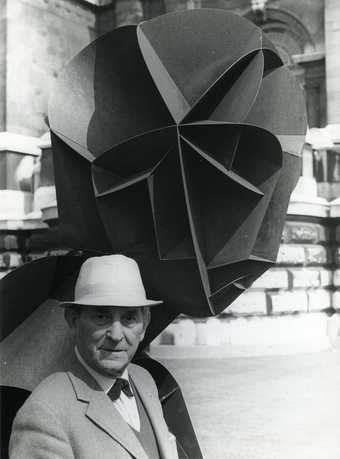

La Chatte, performed by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes with architecture and sculpture constructed by Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner (1927) photographed by Manuel Henri

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019, courtesy Tate Library and Archive

I have been an admirer of Naum Gabo’s work since the 1970s, when I began constructing sets in my studio to photograph. In the exhibition Tektonika at Kunstverein Nürnberg in 2012, the curators connected my work with Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner’s Realistic Manifesto from 1920, suggesting that I shared one of the document’s artistic principles: the importance of time and space.

Borrowing from the constructivist theories about non-objective art that Gabo had defined with Pevsner, my work was presented as an interpretation of the spatial relationships between negative volumes in Gabo’s art, which he created to address the perception of space. You can see this in Gabo’s iconic Head No. 2 1916, enlarged version 1964, which affirms and yet deconstructs the planes of three-dimensionality, while demanding that we perceive a universally accepted object in a new way.

Gabo and Pevner’s manifesto intended to promote a vision of a new reality in the modern age. Thinking about this aim 100 years later, I agree with Gabo’s notion that time and space seem to be implicit in current societal world views, and that art should be in our everyday lives.

Materiality occupied an important role in Gabo’s art too. He used unorthodox art materials that often related to commercial production, such as sheet metal, glass and plastics. With the same motivation in mind, I have used industrial materials marked by scratches and abrasions, the evidence of their human use a depiction of time. The constructions that I make for the camera allow ambiguities of space to manifest in the resulting photographs.

Gabo’s sculptural, transparent acrylic planes, designed for the staging of Sergei Diaghilev’s ballet La Chatte (1926–7), bring together architecture, space and time. The costumes are reminiscent of his Sketch for a Kinetic Construction 1922, capturing the directional force of movement while utilising transparent materials to veil the source of that movement – the body. Meanwhile, his unconventional use of see-through acrylic forms allows the eye to see the construction as line and space simultaneously.

Barbara Kasten is an artist who lives and works in Chicago.