Steve McQueen

Video still from Charlotte 2004

Film, 16mm, colour, back projection, 5 min, 42 sec

© Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery

In recent years, particularly since 12 Years a Slave won three Oscars, including Best Picture at the 2014 Academy Awards, a narrative has wrapped itself around the work of Steve McQueen. He’s the rare case of a visual artist who has ‘gone Hollywood’ while being equally credible in – well, I nearly wrote ‘his initial field’, because to some it might seem that way. From 1992 until 2008, when his first feature, Hunger, was released, McQueen focused on films for galleries, often revolving around a single, highly charged scenario, usually silent, and drawing on forebears ranging from Buster Keaton to Andy Warhol.

In the ensuing decade, during which he also made the movies Shame (2011) and Widows (2018), McQueen has appeared to devote most of his energies to the big screen. Not only is that narrative not really true – McQueen has continued to produce superb filmic, photographic and sculptural work for art venues – but it also falsely positions his artistic work as somehow secondary or preparatory to his cinematic work. As such, Tate Modern’s survey of McQueen’s art, stretching from the outset of his career to a new, specially commissioned work, ought to serve as a necessary rebalancing.

Steve McQueen

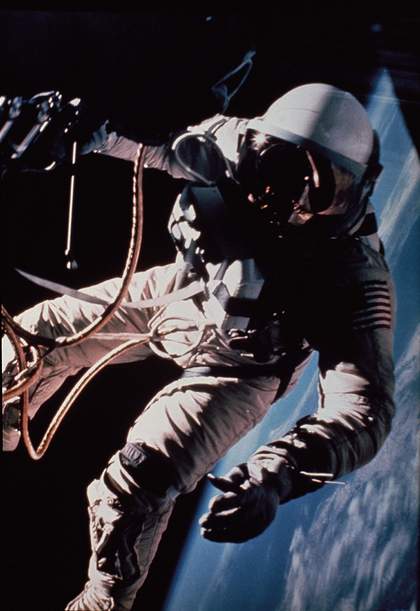

Still from Once Upon a Time 2002

Sequence of 116 35mm slides, colour, transferred to digital file, back projection, sound, 70 min

© Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery

More than this, though, seeing McQueen’s works together affirms him as an artist of profoundly humanist concerns. That’s a weighty designator, but it’s hard to think of a better one. Among the works in the show is Once Upon a Time 2002, a looped sequence of 116 35mm slides that NASA sent into space on the Voyager II mission in 1977. The mid-1970s might still have been a moment of optimism about Earth’s future, but by 2002 – and even more so by now – this work feels like an SOS, as the slides slowly cross-fade from measurements of the Earth in space to our understanding of human anatomy, how we eat, our variety of cultures, dwellings, urbanism, and highways full of the cars that have been, in part, our undoing. Once Upon a Time posits life on Earth as fragile and subject to violence and worthy of remembering. And, on various scales and with substantial emotional heft, it appears McQueen has been doing this all along.

Steve McQueen

Video stills from Exodus 1992/97

Film, super 8mm, colour, transferred to video, 1 min, 5 sec

Steve McQueen. Photo: John Russo.

In his films there is often the potential for something to go badly wrong; sometimes the disaster has already happened, sometimes it is miraculously escaped. In Exodus 1992/97, his first mature work, McQueen follows two West Indian men through London’s streets as they tote potted coconut palms – a symbolic sustaining of culture – through crowds and traffic to the safety of a bus. (In Deadpan 1997, not on show, McQueen achieves something similar by re-enacting the famous Keaton stunt in which the frontage of a house falls on him, leaving him unscathed.) By 7th Nov. 2001, McQueen is recording his cousin telling the heartbreaking story of how he accidentally shot his own brother, went to prison, and triggered his mother’s suicide. Relayed over a still image of the cousin lying prone, head visibly scarred for reasons never explained.

Steve McQueen

Still from 7th Nov. 2001

Single 35mm slide, colour, projection, sound, 23 min

© Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery

McQueen’s cousin speaks about how talking helps, and the artist makes a monument to his pain and boundless regret. Something similar happens in the double-screen Ashes 2002–15. One panel features the smiling, shirtless Caribbean man whose nickname titles the work; he’s on a boat under a blue sky. By the right panel he’s dead, having – as a friend’s voiceover recounts – chanced upon some drugs on a beach, taken them and been shot for it. Ashes, we hear and see, had been a decent, happy young man. The footage shows the patient making of his gravesite by two artisans, before some sheep and dogs roam past it, like the farmer oblivious to the drowning man in William Carlos Williams’ poem Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (1960). McQueen’s larger shrine to Ashes, of course, is the work itself, a tribute, circulating his memory. One guesses that the footage of him was shot in Grenada – where McQueen’s father was born – while the artist was making Caribs’ Leap / Western Deep 2002. Caribs’ Leap juxtaposes two aspects: footage of a beachfront and dock, and an empty sky through which, at intervals, a figure falls, recalling the last Carib Indians’ choice to jump off a cliff rather than be captured by French colonists in 1651. Western Deep, meanwhile, documents black miners in the eponymous gold mines near Johannesburg, stoic under a form of economic slavery.

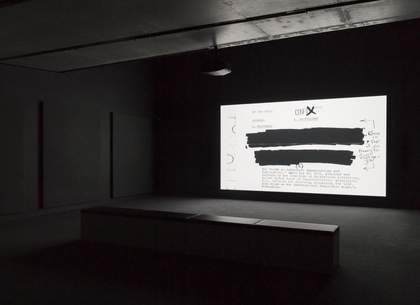

Installation view of Steve McQueen’s End Credits 2012-ongoing, video, single screen projection of HD video sequence of scanned files with an independent audio track, black and white, sound, 5 hours, 38 min

Whitney Museum of American © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery Art, New York, photo: Ron Amstutz

Watching Caribs’ Leap, made the year after 9/11, it’s hard not to think of figures jumping from the Twin Towers, and McQueen’s art has, indeed, increasingly tracked the geopolitical shifts of our time. In the highly economical Illuminer 2001, he lies in a darkened hotel bed, lit blue by the TV screen showing a French programme – with just broken fragments of speech – about American forces being trained to fight in Afghanistan, the whole voicing suspicions about mediated understanding of wars. By 2009’s Static, McQueen is in a helicopter prowling around the Statue of Liberty, closed to tourists after the 2001 attacks and then just recently reopened by Obama. His camera commences close to the green body, a near-abstraction, before assaying the figure from different angles, suggesting the instability of its meaning. (Intermittent bursts of helicopter noise underline a sense of periodic threat.) A decade later, under Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda, Liberty arguably signifies something else again. And when McQueen, in End Credits 2012–ongoing, reproduces the whole of black American singer and activist Paul Robeson’s extensive, heavily redacted FBI file, it’s clear he’s not talking about a bygone age of surveillance.

In 1999, McQueen made the 16mm Cold Breath, in which his fingers stroke, strum and violently twist his nipple. In 2004 he made Charlotte, where, under red light, his finger probes the skin around actress Charlotte Rampling’s eye, pushing it around and revealing, in its lack of elasticity, her ageing. What might those fingers, sometimes delicate and sometimes aggressive, represent? To me, it’s something like quixotic outside forces – flawed life itself, into which racism, inequality and precarity factor greatly – which might cause a man to inadvertently shoot his brother, or die from finding drugs on a beach, or be sent to war and killed, or be spied upon for beliefs, etc. McQueen can’t prevent that; he can only recognise it and testify to it, bring it to consciousness. Against it, his art is in part an act of preservation, partly a reminder of our own temporarily living bodies, and the sanctity of others. It made me think of a work from 2016, a series of glowing black neons repeatedly spelling out, in various handwritings, two words that cut to the heart of McQueen’s heartfelt project. They say, simply, Remember Me.

Steve McQueen, Tate Modern, 13 February – 11 May 2020, curated by Clara Kim, The Daskalopoulos Senior Curator, with Fiontán Moran, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. Supported by the Steve McQueen Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan.

Martin Herbert is a writer and critic based in Berlin. He is associate editor of ArtReview and his latest book, Unfold This Moment, on American artist Carol Bove, is published by Sternberg Press.