Antonio Verrio

The Sea Triumph of Charles II c1674

Oil paint on canvas

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

On 29 May 1660 the Surrey gentleman and writer John Evelyn pushed his way through the crowds on the Strand in London. The streets had been full since before dawn. Wooden rails held people back, and hangings and tapestries flapped from the upper windows of the timber-framed houses. The sight they were all craning to see was a momentous one: the return to London of Charles II after two decades of war and turmoil. Evelyn was a young man – he was not yet 40 – but all that he had already witnessed must have made him feel old. Eleven years earlier he had sat in deep prayer and meditation as King Charles I had been executed for high treason before the Banqueting House at Whitehall.

The procession which bore Charles II took hours to travel the short distance to Whitehall Palace. After 14 years of exile, much of it spent living a frankly unregal life in German inns and Flemish rented houses, the young King, whose birthday it was that day, had been asked to come and reclaim the throne. The irony was not lost on him; he turned to his companion to remark wryly that it must have been his own fault it had taken so long, since he hadn’t met a single person who did not claim to have been yearning for his return.

Jacob Huysmans

James Duke of Monmouth, as St John the Baptist c1662–5

Oil paint on canvas

Private collection, courtesy: The Buccleuch Collections

The relief that people felt was real. The ‘interregnum’ that was now at an end had been a period of political insecurity without parallel in English history. A quarter of a million people had died in the civil war, 200 great houses had been ruined, 10,000 town houses destroyed, and hundreds of towns and villages lay battered and broken by conflict. The King had been executed; the monarchy, the House of Lords and bishops had been abolished; and the Church of England was changed beyond recognition. Almost the entirety of the royal and Church estates had been sold. The castles of England had been deliberately wrecked to make them defensively useless and the great medieval hunting forests cut down to build a naval war fleet. Religious freedom had been instituted and a publishing revolution had taken place, with national weekly newspapers now a staple of English life. Much of this had been achieved through military coercion and in an atmosphere of strict Puritanism.

This tumultuous past was now being swept aside as a traumatised nation colluded to erase its past. The proclamations were clear: this was not in fact the first year of Charles II’s reign, but the thirteenth – all that had gone before was an aberration. The whole pre-revolutionary national regime was reconstructed: a conservative Church of England was restored, religious toleration was reversed, and press censorship reinforced. The traditional calendar of Church feasts and festivals was reinstated and the endless search for moral purity that had characterised the 1650s was replaced, at Charles II’s court at least, by a deep hedonism and self-indulgence.

Royal Oak Cup designed by Richard Morrell, 1676

The Worshipful Company of Barbers

The consequences were a godsend to the merchants and mercers, artisans and artists, whose businesses had struggled amid the parsimony and political instability of the decade before. Nothing much short of an explosion in spending and building, commissioning and contracting followed. The royal palaces had to be recommissioned – new furniture made and interiors fitted – the hunting parks re-established, country houses rebuilt. In London, the Great Fire of 1666 added a further massive task to the national programme of rebuilding: 13,000 more houses and 87 more churches required reconstruction. All this acted as a tremendous boost to the economy and to the artistic output of the era. The exuberant, grandiose style that would later be called Baroque was not a creation of the Restoration – Oliver Cromwell’s politicians had built Baroque houses for themselves – but with political and economic stability, and a cadre of affluent people who were very much at ease with expenditure on a colossal scale, it suddenly took off.

Nicholas Hawksmoor and Christopher Wren

St Paul’s Cathedral: South Elevation, Revised Design c1702

Grey ink shaded with grey wash, pencil and red crayon additions

The Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

Charles II’s court at Whitehall was an expression of the man and his experiences. No English sovereign since the fifteenth century had known what it was to be an outcast. Charles II, by contrast, had felt the bitter privations and humiliations of exile. Without palaces or pensions, army or administration he had roamed Europe in search of support for the whole of his twenties. When his Restoration came he threw himself into kingship and all its trappings with gusto. A bachelor until 1662, he was always promiscuous and loved beautiful and charismatic women. A series of his mistresses and illegitimate children quickly accumulated in the apartments of Whitehall. Peter Lely succeeded fellow Dutchman Anthony van Dyck in the post of principal painter to the new King and captured these voluptuous beauties in oil. Meanwhile Christopher Wren, as surveyor of the King’s works, would lead national architectural projects, including the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral. Court culture was humorous, playful and licentious; the riotous, ribald poetry of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, conjured up a telling caricature of the age. But Charles II’s appetite for pleasure was not borne of laziness, and he was physically and intellectually restless throughout his reign. He loved horse racing and sailing, walking and swimming. He was also fascinated by the flowering of scientific research and discovery, which had blossomed during the chaos and breakdown in control of the 1640s, and a room in his own apartments was set up as a laboratory for scientific experimentation.

View of the Heaven Room in Burghley House, Cambridgeshire, painted by Antonio Verrio, 1697–9

Photo: Will Pryce

There was, however, trouble ahead. Charles II and many others had expected that the parliament elected in 1660 would seek some sort of compromise – especially when it came to religion – between the strict religious uniformity of the old Anglican church and the far broader religious toleration of the 1650s. But the desire for revenge and retribution was strong, and in the early 1660s religious toleration was reversed. All English people were required to attend Anglican services and to swear loyalty to this form of religion in order to be able to participate in national political life as an MP or government official of any sort. This forced thousands of people out into the cold: Quakers and Presbyterians, Catholics and Jews. The tension this began to bring about soon mounted. The new establishment regarded the non-conformists as untouchables, while the fact that well-connected Catholics were tolerated at court riled many. The catalyst for a new crisis would come horribly close to home when Charles II’s brother and heir, James Duke of York, converted to Catholicism. While discreet Catholicism practiced in private family chapels had been tacitly allowed, the prospect of a Catholic becoming King of England was profoundly alarming. The brief reign of James II was to prove the disaster that many had predicted – the new King’s authoritarian ways and lack of political sensitivity proving as unpopular as his religious preferences. James II’s enemies formed a secret pact with the King’s daughter, Mary and her husband, William of Orange. In 1688, a flotilla of 500 ships and 20,000 men brought the Dutchman over and James II fled. It may have been bloodless and badged the ‘Glorious Revolution’, but it was unquestionably an invasion. Three months later, Parliament offered William and Mary the throne as double sovereigns.

Godfrey Kneller

Oil Modello for an Equestrian Portrait of William III 1714

Oil paint on canvas

Paleis Het Loo, Apeldoorn, Netherlands

A Dutchman was now King of England and a new contractual monarchy brought into being by the will of Parliament. With the Bill of Rights, sovereigns of England now ruled by parliamentary consent rather than divine right, and the Act of Toleration that followed soon after made non-conformist worship legal in England once again.

The Baroque style that had characterised architecture and portraiture of Charles II’s court was an international phenomenon. Charles II’s first cousin Louis XIV of France adopted it with the splendour and scale for which he was famous. His great building schemes, Les Invalides in Paris and the gargantuan aggrandisement of Versailles, expressed his megalomaniacal ambitions. Charles II had no such ambitious; he wished for peace and pleasure, affluence and amusement. He remodelled the interiors of his palaces with great sensual allegorical paintings, but it would be others in England who would undertake the grand projects to which the flamboyant language of the Baroque was best suited. William of Orange was Louis XIV’s greatest enemy; the two men had pitted their armies against one another in a decades-long series of campaigns in the Low Countries. With William’s accession to the English throne, England was drawn into this conflict. Paintings now celebrated military commanders rearing on horseback, tapestries were battle scenes, and even buildings became military monuments. Wren’s ‘hospitals’ at Chelsea and Greenwich provided homes for injured soldiers and sailors, and the battle of Blenheim was commemorated by the great palace that Queen Anne funded for her commander Duke of Marlborough and his wife (and her favourite) Sarah.

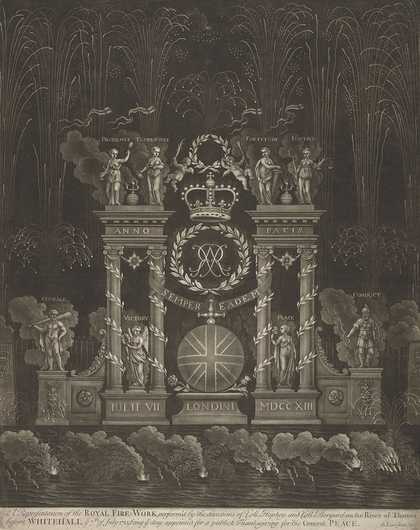

Bernard Lens

A representation of the Royal Fire-work perform’d by the directions of Coll. Hopkey and Coll. Borgard on the River of Thames before Whitehall, the 7th of July 1713, being the day appointed for a publick Thanksgiving for the General Peace 1713

Mezzotint on paper

The British Museum

The accession of William III brought the apogee of the Baroque style in England, but it was also to be its downfall. For the shift in power that it represented – from the monarchy to parliament – sowed the seeds of its decline. The new era saw the rise of the professional politician, and the role of ‘prime minister’, whose power originated as much in a parliamentary majority as it did in royal favour. The magnificent language of the Baroque – overwhelming, majestic, emotional – was passing, giving way to the more controlled style, and altogether less exciting world, of the eighteenth century.

British Baroque: Power and Illusion, Tate Britain, 5 February – 19 April 2020, curated by Tabitha Barber, Curator, British Art 1550–1750, Tate Britain, with David Taylor, Curator of Pictures and Sculpture, National Trust, and Tim Batchelor, Assistant Curator, British Art 1550–1750, Tate Britain. Supported by White & Case, with additional support from the Baroque Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons.

Dr Anna Keay is a historian and Director of The Landmark Trust. Her books include The Magnificent Monarch: Charles II and the Ceremonies of Power (2008) and The Last Royal Rebel: The Life and Death of James, Duke of Monmouth (2016).