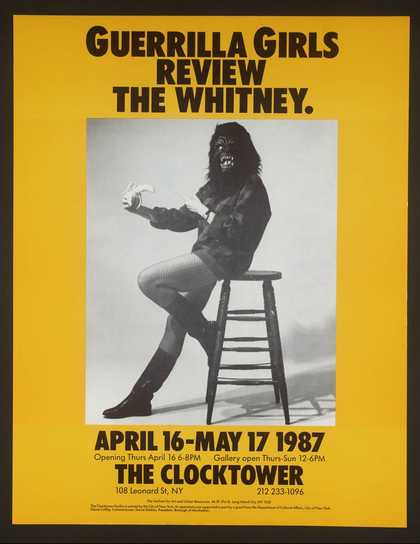

Thirty years ago, the Guerrilla Girls in New York were protesting against the male domination of art museums. Forty years ago, African states were appealing to Europe to return artworks stolen during the colonial era. Fifty years ago, artists like Hans Haacke were lamenting the influence of dubious sponsors on museums, calling for resistance to the power of dirty money.

And what has happened? Over all these decades, the museums, which like to see themselves as bastions of critical thinking, enlightenment and self-reflection, did what they like to do best: they showed themselves to be resistant to their times. Presumably they were hoping the protests would disappear of their own accord. But that didn’t happen. On the contrary, the criticism has intensified considerably. More people than ever are now interested in the ethical dimension of aesthetics, in the question of what hides behind the veneer of art, and behind the thick walls of the museum. Who has the power? Where does the money come from? How equitable and democratic are these institutions?

Sometimes the protests are against dubious trustees (as was recently the case at the Whitney in New York), sometimes against sponsors and their inglorious dealings (the Sydney Biennale), sometimes against the activities of museums in authoritarian states like the United Arab Emirates (the Guggenheim). And lately, curators, too, must expect outrage if, for example, they once again invite fewer female than male artists to be part of their exhibition. Quite clearly, the museum in digital modernity is a politicised museum.

At last, the heel-dragging is over; the problems can no longer be put aside. At last, it is possible to discuss abuses of power and responsibility. And yes, at long last, many museums are beginning to open up to all this. Like all major institutions – political parties, religious institutions, the media – they can no longer avoid renegotiating the way they see themselves. Welcome to the present!

The protests are by no means directed solely against the institutions themselves, however, but also against what is on show inside them: the works of art. Two years ago, 12,000 people urgently called for a painting by Balthus to be removed from the Metropolitan Museum in New York because some felt it was like a form of child pornography. There were also calls to remove a video work about dog fighting by Peng Yu and Sun Yuan from the Guggenheim in New York due to the levels of cruelty it featured, a demand willingly met by the museum. Something similar occurred recently in London: paintings by the artist SKU were covered with grey cloths because visitors to the Saatchi Gallery had complained that the artworks hurt the religious feelings of Muslims.

There have been quite a few such events in recent years: people show themselves to be hurt and aggrieved, they demand that paintings and sculptures should be removed and sometimes even destroyed. For some artists, there have even been calls for a general ban on exhibiting, as in the case of the painter Chuck Close who has been accused of sexual harassment by several women. And the National Gallery in Washington really did suddenly decide to cancel a long-planned Close retrospective.

This, too, is clearly part and parcel of the politicised museum: social and moral conflicts make their entrance and art often becomes a bone of contention in a new culture war. Unlike in postmodernity, where all questions of meaning and signification were transformed into a cloudy nothing, now the struggle is over the big picture again, over the claim to normative validity. Art, one might think, is being taken seriously again. However, this is only half of the story.

For the disputes are rarely about aesthetic values. When, for example, Dana Schutz is challenged for using a photograph of a murdered black boy as the model for one of her paintings, then the criticism is aimed not at the composition or her choice of palette. The charge is that of cultural appropriation. Schutz, as a white woman, took a motif that - some black activists claimed - is the sole preserve of black artists, for which reason her painting must be destroyed.

Many current conflicts are dominated by such demands based on social issues and identity politics. This tends to obscure the fact that, for a long time, entirely different rules were unquestioningly thought to apply to art than those applying to the real world, and that museums saw themselves as free spaces where anything could be thought and tested by anyone. Artists were not supposed to be virtuous, their art was not supposed to be respectable. On the contrary, artists were considered especially innovative and radical if they departed from conventions, breached taboos and left the public seriously rattled.

Of course this also drew criticism. Some people even wanted to prevent the funding of art that ‘denigrates, debases or reviles a person, group or class of citizens on the basis of race, creed, sex, handicap, age or national origin’. But such demands almost always came from reactionary quarters – in this case, in America in 1989 from Jesse Helms, an ultraconservative. For most museums at the time, it was clear that they should protect the freedom of art. It would have been unthinkable for a collector such as Charles Saatchi to cover up a shark pickled in formaldehyde or an image of the Virgin Mary featuring pieces of elephant dung. Only now, in the age of cancel culture, are we seeing a dwindling willingness on the part of many exhibition venues to protect art from protest.

The museums of digital modernity are no longer the museums of modernity, and there are good reasons for this. They have realised that the classical history of art as progress, which reached its peak in the heroism of the avant-garde, has many blind spots, because it is a story that has most often been told from a Eurocentric, male, white perspective. The more cosmopolitan the museum-going public becomes, the more pluralistic society is, the more justified are the calls for the canon of art to be broadened and for traditional narratives to be relativised.

With this long-overdue opening up, however, the museums are facing a dilemma. And this dilemma is part of why they are acting so defensively in the new culture wars. Because they have come to see that the desired relativisation of the canon has an unpleasant side effect: the modern idea of free, radical, provocative art is also being relativised. Now it is just one idea among many, and those who continue to defend the notion of free art against all protest, praising the ideal of autonomy as a major achievement of modernity, is soon accused of clinging to an old, authoritarian worldview and of approving the denigration of minorities.

The dilemma is further aggravated if the canon is to be not only broadened but also made more equitable in the sense of social justice. In digital modernity, many museums are seeking such justice – they want to be museums of inclusion. No one should feel that they have been rebuffed or left behind. Instead, the collection should be at least as diverse as its visiting public. Because all visitors, regardless of their gender, skin colour or national origin, should find themselves here.

Almost inevitably, however, this jeopardises the freedom of art, which has always also been the freedom of the scandalous and the ambiguous. The more important it becomes that everyone feels comfortable and equitably represented in the museum, the more difficult it becomes to defend the autonomy of art as an intrinsic value. Such a defence must be justified, not ethically, but primarily in aesthetic terms. It needs quality criteria for good art, for instance, in order to credibly argue that even perpetrators of violence can be great artists that should find their place in the museum. Or that the artistic value of a painting has nothing to do with the skin colour, gender or nationality of the painter.

But many arguments of this kind are experienced as unworldly or discriminating, precisely because they obey not ethical but aesthetic standards, which are ultimately unlikely to lead to the same selection. A museum of ethics must seek social compromise, while a museum of aesthetics focuses on uncompromising art.

We are dealing here, then, with a vicious circle: the smaller the part played by artistic qualities in the selection of works to be collected, the more those who want to see their social and political ideals reflected, and who want even historical art to be measured by the moral standards of the present, will feel encouraged in their protests and calls for boycotts. The more these standards shape the programme of the museums, however, the harder it will become for the unconditional freedom of art to stand up for its absurdities and transgressions.

The good thing about such a dilemma is that it awakens energies. It forces museums to face up to unfamiliar debates and to explain better than ever before why they value autonomous art. They need to listen more closely to the expectations of their public – not necessarily in order to fulfil them, but in order to give a genuine response to the ethical critique, a response shaped by aesthetics. Museums are political places and they are places of art. They are torn between the two. Things could hardly be better.

Hanno Rauterberg is the art critic on the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit. His most recent book, published by Suhrkamp, deals with the question: How free is art?

This article has been translated by Nicholas Grindell.