Close and distant encounters with Neon Rice Field

The subtle aroma of raw rice pervades the central rotunda at Tate Britain, London, and I sense before I see the source of its emanation: Vong Phaophanit’s Neon Rice Field 1993 (Tate T14130). The work’s title points to its materials: six lines of neon tubes and several tonnes of rice, arranged into a rectangular formation that occupies a third of the museum’s neoclassical Duveen Galleries (fig.1).1 Pearly grains gather evenly, rising and falling into ridges and furrows, irrigated not by water but by light; their papery dryness is warmed and softened by the glow of red rivulets. Bright bolts like luminous veins or seams lift the undulating ‘field’ of rice, which appears to float ever so slightly. Like a raft perhaps, but also like waves … an unlikely vessel and would-be watery body, hovering horizontally, and humming, almost imperceptibly.

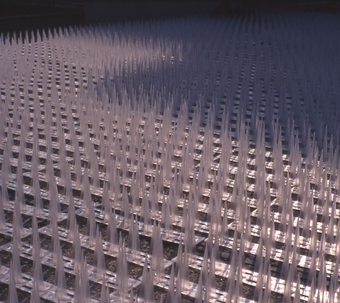

Fig.1

Vong Phaophanit (with Claire Oboussier)

Neon Rice Field 1993 (installation view, Duveen Galleries, Tate Britain, London, 2023–4)

Rice and neon tubes

Displayed: 15000 x 5000 mm

Tate T14130

As the scent of uncooked rice travels and expands the work beyond its physical parameters, beyond and before fields of vision, I locate it, and it locates me. The familiar fragrance brings forth the blackened metal of a tall, precious tin in the dark, sitting in an airless understairs cupboard, amid boxes and containers crammed into its recesses. I recall the semi-hollow sound and feel of the steel resisting unpractised fingers as they seek to prise off the airtight lid, to scoop out two, three or four cups (depending on who is home), taking care not to spill a single grain; the mesmeric ‘chhhhh’ as they pour, the mellow waft before washing and steaming, promising bowls heaped full with soft, satisfying mounds. This minor madeleine memory may resonate with others unmoored and marooned by non-centric/ex-centric, ‘eccentric’, or (e)strange(d) heritages.2 I am disorientated by its unexpected summoning, and my transportation to an intimate domestic space far from the vast Duveens. I file it away.

Over the past thirty years, I have returned time and again to the same slightly washed-out images of Neon Rice Field and have read the scant literature available. Over the last ten of those years, I have talked many times to Phaophanit and his long-term collaborative partner, Claire Oboussier. Yet this visit to Tate Britain in 2023 was my first embodied experience of Neon Rice Field, and despite the recognition, I also recognise that there was misrecognition, distraction and disorientation. With hindsight, I realise I had failed to attend to the work before me. I do not ‘know’ the work at all.

Neon Rice Field has taken a slightly different form each time it has been shown. First exhibited in 1993 at the Serpentine Gallery, London, and in the Aperto section of the 45th Venice Biennale, the installation was reprised for Phaophanit’s Turner Prize nomination at the Tate Gallery, London, in the same year. It was subsequently installed for the launch of the Weltkunst Foundation Collection at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (IMMA), in 1994. It would be another twenty years before the work entered the Tate collection in 2013, and a further decade before Neon Rice Field would be shown again as part of Tate Britain’s collection rehang in 2023. The work remained on display until the end of January 2024.

This essay looks closely at a range of texts relating to Tate’s acquisition, interpretation and display of Neon Rice Field in relation to two of Phaophanit’s earlier works, made in collaboration with Claire Oboussier, also in the Tate collection: What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten 1991 (Tate T12860) and ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ 2006 (Tate T12815). Between Tate Gallery Records, archival documents and the museum’s online and in-gallery texts, I find glimpses of institutional aspirations to address past oversights; gaps and tensions in concurrent processes relating to the artworks’ acquisition, display and storage; and evidence of errors and repeated inaccuracies in interpretation.3 My analysis of Tate’s archive and public-facing texts attempts a ‘micro-art-historical’ approach, with several questions in mind: Why did it take three decades for the museum to acquire and redisplay Neon Rice Field? How, through the limited accounts available, are audiences encouraged to understand or ‘know’ (or forget) the work?4 How do the shifting narratives that have accrued around Neon Rice Field reflect broader interpretative tendencies, and the perpetuation of wider problematic cultural narratives over time? Moving from close textual readings to the historical ‘flashpoint’ of the 1993 Turner Prize and the press reception of Neon Rice Field then and now, I end with some thoughts on how museums might move from revisionism to re-visioning: to re-frame, re-read and re-imagine artworks and artists, releasing them from the burden of othering.

In tune with the unsettling intent and effects of Phaophanit and Oboussier’s work, I open and close this article with my reflexive, embodied experience of Neon Rice Field, by way of acknowledging my subjectivity as an artist and academic, navigating the tensions between institutional histories, practices, expectations and relations.

‘Marginalia’ as method? A micro-art-historical approach

Nothing but a moment of the past? Much more perhaps, something which being common to the past and the present, is more essential than both.5

In quoting Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, Phaophanit evokes the way in which Neon Rice Field exists in several moments in the physical and reimagined past and present. The artwork is essential to a particular story of ‘British art’, in the 1990s and now, yet also exceeds its limiting narratives. This case study considers these moments through the documentary traces surrounding the artwork as an object and event that ‘takes place’ intermittently over thirty years. I look closely at the museum’s ‘marginalia’, some public, some hidden. Short in form yet long in impact, these include descriptive online summaries, gallery wall texts, artwork captions, archival annotations, fleeting critiques in acquisition notes and fragments of correspondence. With an approach that might be described as ‘micro-art-historical’, my retrospective reflections on ‘marginalia as method’ follow intuitive investigations into the work and its traces. I touch on some of the principles of the micro-historical approach below, while echoing the caution with which the historian Carlo Ginzburg approached a ‘retrospective investigation’ of microhistory as method.

Ginzburg’s research in the 1970s focused on the ‘reduced scale’ and ‘minute analysis of a circumscribed documentation, tied to a person who was otherwise unknown’.6 Countering the universalising grand narratives that had hitherto characterised dominant Western epistemologies, such attendance to the micro, minute, marginal or missing can throw into relief ‘conditions of access to the production of documentation’, which ‘in any society … are tied to a situation of power and thus create an inherent imbalance’.7 It has been taken up as a critical tactical intervention across other disciplines in subsequent decades, with the literary historian Heather Murray noting its application to broader phenomena over time:

While the methodology called microhistory is rooted in the attempt to incorporate peripheral or marginal events, figures, and communities into the historical picture (thus the prefix micro, which has continued to adhere), microhistory as a method need not necessarily be confined to micro phenomena (or indeed … need not be restricted solely to past phenomena at all).8

Meanwhile, recent scholarship has reflected on the growing popularity of microhistory as a method for display and interpretation in museums and galleries. The historian Fabrice Langrognet, for example, discusses its use for ‘enhancing the relatability of migration stories’ in heritage museums, employed to acknowledge ‘the value of singular narratives and first-person voices’.9 However, the recourse to migration stories in the interpretation and display of visual art is contentious. As a device for displaying works by global majority artists who have historically been racially and ethnically minoritised, the migration story can overdetermine artworks with socio-political narratives that privilege biography over aesthetic, synaesthetic, material, formal, experiential or philosophical concerns. Thus framed at a remove, no matter how expanded and diversified, such a strategy leaves dominant and domineering histories and canons intact.

My micro-art-historical approach is therefore tentative, and draws on theorisations and methodologies developed over the last fifty years from postmodern, poststructuralist, Black, intersectional, postcolonial, decolonial, indigenous, queer and feminist perspectives.10 Against the conventions and constraints of Eurocentric art history, ethnocentric biography or migration stories, I concentrate on the sparse available ‘scraps’ (a tendency, Ginzburg notes, of postmodern historiography) to attend to Neon Rice Field as both singular, multiple and continuing event; and past, recent and recurring phenomena.11 While the documentation at hand may be ‘insufficient to form a sharply focused portrait’ of the artist(s) or the museum, I contend that a close reading of the assembled texts can enable, as Murray observes, the ‘discernment of patterns and connections’ that reveal the ‘largesse and lacunae’ of some histories over others.12

By considering the narration and curation of Neon Rice Field through fragmentary documents evidencing processes of acquisition and interpretation, I seek to raise questions around the ‘accounts and accountability’ of museum practices, the effects of institutional framings on broader histories of art, and their part in perpetuating societal prejudices and structural discriminations.13 I argue that the case of Neon Rice Field reflects and reinforces broader critical and interpretative tendencies in collection practices, including the persistence of orientalising, exoticising views embedded in the cultural inheritance of Britain’s colonial and imperial past.

If, to quote Ginzburg, the ‘back and forth between micro- and macrohistory’ affirms reality as ‘fundamentally discontinuous and heterogeneous’, it is perhaps in ‘the inevitable gap between the fragmentary and distorted traces of an event … and the event itself’ that opportunities open up for recognition, redress and reimagination.14 Addressing these schisms not as gaps to be filled but fissures that may reveal the complex possibilities of Phaophanit’s and Oboussier’s solo and collaborative practices, I return once more to the work itself. I began and will end this article with my own ongoing, interrupted and ever-changing encounter with Neon Rice Field. Like the museum, the collection, the documents, the archive and the artwork, my account, too, is unstable. Heeding Ginzburg again, I am mindful that ‘the obstacles … hesitations and silences … the hypotheses, the doubts, the uncertainties became part of the narration.’15

Neon Rice Field, 1993

In 1993 Phaophanit was the visible outlier in the line-up of artists nominated for the Turner Prize.16 Hitherto unknown, he was the first artist with Southeast Asian heritage to be shortlisted for the prize.17 As the art historian Pamela Corey notes, he was also ‘the only non-Caucasian nominee within the group whose ethnicity was not legibly moored to Britain’s imperial past, unlike 1991 Prize winner Anish Kapoor’.18 The media coverage and cyclical controversies that had accompanied the award since its inauguration in 1984 reached something of a frenzied peak in 1993. Debates intensified around the question of what constitutes ‘British’ art, amid routine dismissals of modern art as rubbish. The prize’s place in the public consciousness had been elevated by live broadcasts on Channel 4, the independent terrestrial television station that had sponsored it since 1991. In 1993 this was heightened by the K Foundation’s announcement of their £40,000 ‘Anti-Turner Prize’ for ‘the worst artist in Britain’, to be selected from the same shortlist as the Turner Prize and awarded on the same night.19 Looking back on the 1993 Turner Prize, Tate’s website reports the high levels of interest from both the public and the press that year, as ‘Unconventional art materials provoke[d] debate’:

Visitor numbers this year rose significantly and the public response was misjudged by many of the press who continued to find fault with the Prize. Vong Phaophanit’s Neon Rice Field was appreciated by a number of visitors for its serene beauty, whereas others, in particular the press, questioned the artist’s use of unconventional materials and his right to be shortlisted (he is of Laotian origin).20

The text alludes to the widespread questioning of Phaophanit’s eligibility for the prize, intended for ‘a British artist under 50’. By the following year Tate had clarified this criterion, stating that ‘British’ applies to artists born and working in the United Kingdom.21 The 1994 award went to Antony Gormley, with one critic noting, ‘The shortlist for last night’s prize could not generate the level of indignation which greeted 1993’, namechecking Phaophanit and Whiteread, on whom much of the media had focused.22 It is worth stressing the numerous instances in which such ‘questioning’ and ‘indignation’ served as vehicles for insidious, latent and overt expressions of racism. Corey points to the examples of critic Brian Sewell’s ‘coyly innocent query’ in a casual aside in the Evening Standard – ‘(but I thought the Prize, according to the rules, was for a British artist?)’;23 and a ‘disturbingly blunt and coarse’ cartoon in the Independent, depicting the artist as ‘an Asian peasant in a conical hat’.24 Oboussier recollects the reception of the work, and the artists’ shock at the inflammatory press coverage:

Neon Rice Field was very well-received by the establishment, which was a huge surprise. There was no expectation on our part that this piece of work would somehow become a flashpoint at that moment in the art world in this country. It immediately became appropriated and grasped by a narrative that needed to constrain it, and then, as has been well-documented, people start narrating the work in certain ways and imparting quite rigid meanings. It was in the broadsheets and the red tops [tabloid papers such as the Daily Mail], on the front of The Independent, in The Times and The Financial Times, and there were racist cartoons of Asian people.25

When I conducted a studio visit with Phaophanit and Oboussier in 2017 for an ongoing film project, we sifted through an archival box of newspapers and cuttings, unopened since 1993. In the following exchange, the artists revisit headlines attesting to the latent and outright racism fuelling this ‘flashpoint’:

[Phaophanit] This is interesting: ‘Which is easier to understand, Titian’s the Death of Actaeon, left, showing a man with an animal’s head being torn about by dogs, or Phaophanit’s Neon Rice Field, a simple Asian sunrise?’

‘Sharpening knives greet Turner nominees.’

Here, I am a ‘Vietnamese-born installation sculptor’.

‘Vong Phaophanit unexpectedly shortlisted’.

‘The trauma of exile from Laos and his family is the main inspiration of his art.’

There’s a nice cartoon here: Tate Gallery Shop, Uncle Ben’s rice on sale.

[Oboussier] ‘The personification of British art.’

[Phaophanit] ‘All that goes with the grain.’

[Oboussier] ‘This seven-tonne pile of rice could make a meal for 10,000 people – but is it art?’ There’s also a cartoon: ‘I once tried to do modern art but it all got stuck to the bottom of the pan’.

[Phaophanit] ‘Careful what you say about the Turner Prize this year, it could be your dinner.’

[Oboussier] That little cartoon is quite – ‘win so and new tong’ – Windsor and Newton. Look at the image.26

Corey argues that such reductive ‘East meets West’ tropes and neo-orientalist commentary became ‘baselines for public criticism surrounding Neon Rice Field, invoked by its title and materials, and stereotypical perceptions of its author’s ethno-national identity’.27 While the openly offensive narratives may since have abated, the underlying colonialist and imperialist worldviews that frame them have not. These continue to underlie the broad readings and misreadings of the work, as well as misidentifications of the artist(s), perpetuated over the last thirty years.

Tate acquisitions: 2008 and 2013

Neon Rice Field is one of three works in the Tate collection attributed to Phaophanit. The first two entered the collection five years earlier, in 2008. What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten (fig.2) is an installation made from bamboo poles, metal and light. It was first created by Phaophanit at Chisenhale Gallery, London, in 1991, and then re-created at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, the following year.28 ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ (fig.3) is a single-channel video work made in collaboration with Oboussier and commissioned by the community-based art and education project The Quiet in the Land, which took place in Luang Prabang between 2004 and 2008.

Fig.2

Vong Phaophanit

What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten 1991

Bamboo poles, metal and light

Dimensions variable

Tate T12860

Fig.3

Phaophanit and Oboussier

‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ 2006 (video still)

Video, projection, colour and sound (mono)

33 min

Tate T12815

A double acquisition note, co-written by the Tate curators Robert Upstone and Alejandra Aguado, indicates that the two works were purchased at the same time. The note acknowledges the museum’s decision not to acquire Neon Rice Field in 1993, when Phaophanit was nominated for the Turner Prize:

Vong Phaophanit is not represented in the collection and it has been the aspiration of curators to correct this. When he was short listed for the 1993 Turner Prize Tate considered acquiring Neon Rice Field but did not pursue it, partly because of the difficulty of obtaining new supplies of Laotian rice each time it was installed.29

The curators’ aspiration to ‘correct’ their previous decision implies recognition of a past error of judgement, although the reasons for this error are not fully given. The partial justification is based on a misapprehension regarding the supposed requirement of ‘new supplies of Laotian rice’ for each installation of the work. Given that the rice for all three exhibitions at the Serpentine, Venice and Tate had been provided by the American Rice Council, this makes for an odd statement, which the artists describe as ‘utterly bizarre’:30

The reference to Laotian rice is completely fictitious and quite disturbing on many levels. It introduces a sense of exoticism and gives the erroneous impression that [Phaophanit] specified the use of Laotian rice over other kinds of rice, implying some sort of cultural specificity of the material. In fact, exactly the opposite was and is true: the US provenance of the rice adds a hermeneutic layer that disturbs ‘easy’ readings.31

The difficulty of sourcing Laotian rice was entirely unfounded, evidencing an underlying essentialism that can be discerned in the museum’s later collection texts on the work. What, then, were the other reasons behind the rejection of Neon Rice Field when it was first offered in 1993? Beyond the misrepresentation of the work’s material requirements, what other factors and assumptions have compounded this gap in the collection and errors in the archive, over the long history of the institution’s relationship with the artists and their work?

What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten and ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ were presented to the Collections Committee and Board of Trustees in May 2008. Their acquisition note frames the works under consideration with the above-mentioned reference to Neon Rice Field, and describes the installation What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten as a ‘signature piece which utilises materials that have formed the identity of Phaophanit’s most characteristic work. It is also important for establishing his reputation in Britain at the Chisenhale Gallery and Ikon, Birmingham, in 1991–2.’32 The juxtaposition with Neon Rice Field and its historical proximity suggest a strategic comparison, implying a compensatory or surrogate purchase for the opportunity passed up many years earlier. Although the acquisition note registers some reservations, anticipating the cost implications and time-consuming installation of individual pieces of bamboo, these factors are ‘not considered prohibitive’ in relation to the potential to adapt the work for spaces in Tate Britain, Tate Modern or Tate Liverpool.33 What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten was acquired and displayed at Tate Britain at the end of 2008.34

Written towards the end of the display’s run in spring 2009, correspondence between art handling, curatorial and conservation teams at Tate reflects gaps and overlaps in the timelines and decision-making processes pertaining to the installation’s acquisition and exhibition. The pre-acquisition condition report was completed while the work was already on display.35 Questions were raised after display around the short- and long-term costs of replacing bamboo poles and steel fixings, due to anticipated and unexpected damage caused by the public’s interactions, and the relative merits of long-term storage over fabrication.36 A month after deinstallation, the correspondence reveals uncertainty as to whether the artist provided a manual about the artwork and if so, who might have received this.37 It is unclear from the records whether a suggestion to recycle the bamboo was taken up, although this seems likely given that there were, at the time, ‘no future plans for display’.38

The work was presented for acquisition together with ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ as representative of ‘different aspects of [Phaophanit’s] practice … from different moments in his career’.39 The acquisition note acknowledges the video’s potential contribution to the museum’s moving-image holdings, an aspect of the collection under development: ‘More broadly it would also add greatly to Tate’s representation of this medium’.40 Nevertheless, in their interpretation of the video, Upstone and Aguado stress the continuity of projected themes over formal shifts, stating that the work ‘develops further Phaophanit’s concerns about his relation to his cultural identity, and about the nature of language and memory’.41 The curators do not acknowledge the artist’s collaboration with Oboussier; perhaps to do so would be to undermine the singular, cultural-identity-driven narrative of the artist and his work that had been circulating since the 1990s.

Phaophanit and Oboussier’s offer of two works as a package was a mutually beneficial proposition for the artists and the institution. For Tate it provided a means to redress past oversights, ongoing omissions and current areas of collection expansion. For the artists it asserted their continuing and evolving practice, beyond what Oboussier has described as the ‘flashpoint’ of the Turner Prize.42 However, What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten has not been exhibited since 2009, and no screening of ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ has been mounted since it was first shown in the year it was acquired.43 Notwithstanding the many conditions and factors that shape programming decisions, this suggests a certain haste to make visible the artists’ belated entry into the collection without clear commitment to sustaining the works’ subsequent presence in the galleries.

Tate’s hesitation over purchasing Neon Rice Field in 1993 opened up an opportunity for the Weltkunst Foundation, which bought the work in 1994.44 Neon Rice Field was installed during the same year at IMMA to celebrate the launch of the Weltkunst Foundation Collection, and remained there on long-term loan until 2010.45 Three years later, the Weltkunst Foundation offered six artworks as gifts to Tate, by Hannah Collins, Rose Finn-Kelcey, Avis Newman, Jacqueline Poncelet, Richard Wilson and Phaophanit. Neon Rice Field was thereby returned to Tate, twenty years after it was first installed at Tate Britain. The provenance of the work is listed on the Tate website as ‘Presented in memory of Adrian Ward-Jackson by Weltkunst Foundation’, pointing to relations of patronage. What the language of benevolence and provenance does not reveal are the wider networks and hidden connections between individuals and institutions that can significantly impact an artwork’s trajectory and an artist’s practice.46 In the case of Neon Rice Field, the influence of Declan McGonagle, Director of IMMA, was key. Phaophanit recalls:

I met Declan McGonagle … in 1993 – he was one of the judges for the Turner Prize. Neon Rice Field was acquired by the Weltkunst Foundation, and that collection went to IMMA. So we were invited to Dublin to install the work for the opening, and after that Declan suggested the idea of a commission that became Line Writing [1994].47

The fifteen-year period between the making of What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten and ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ (1991 and 2006) echoes the interval between Phaophanit’s Turner Prize nomination and his work’s entry into the Tate collection (1993 and 2008), as well as the gap between Tate’s first acquisition of Neon Rice Field and its eventual redisplay (2008 and 2023). I draw attention to these symmetries to stress the breaks and continuities: to question the persistence of institutional lacunae and their perhaps inevitable lag in relation to artistic practices. I consider some of the missed connections and continuities between Neon Rice Field, Line Writing and other works across Phaophanit and Oboussier’s practices towards the end of this essay.

Artists, authors, collaborators

Phaophanit’s long-term, evolving collaboration with Oboussier is integral to his creative practice, yet there is little evidence of Tate’s engagement with this in the acquisition process and limited acknowledgement in Tate’s interpretation texts. Phaophanit and Oboussier met as students in Paris in 1985, where they began developing an experimental collaborative dialogue. Their individual and shared practices continued taking shape through the 1980s, with collaborative projects in Brighton and Bristol, group shows and experiments in expanded cinema that would inform later works such as ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ and the later IT IS AS IF 2015.48 As the press’s reception of the 1993 Turner Prize exhibition exemplifies, Phaophanit’s rapid institutional recognition in the 1990s came with reductive proclamations about the artist and his work. The gradual formalisation of Phaophanit and Oboussier’s collaboration since the 2000s has increasingly tested the tensions between individual, institutional and collaborative narratives.49

Dialogic in nature, Phaophanit and Oboussier’s practice poses a potential challenge to institutional terms of value and recognition, disrupting dominant identity-based readings of Phaophanit’s work, not only in the context of British art but also of Black British art. Referring to the exhibition Phaophanit & Piper (1995) at Angel Row Gallery, Nottingham, in which the artist and curator Eddie Chambers, one of the Black Arts movement’s founding figures, retrospectively placed Phaophanit in the same frame as the Black British artist Keith Piper, Corey notes that Phaophanit’s work ‘sits uneasily’ within such narratives. Corey points out that Chambers’s essay characterising Phaophanit’s work as centred on questions of history and identity is in fact challenged by ‘From Light’, a text by Oboussier in the same exhibition catalogue, which counters the projection of such narratives with far more ambiguous possible meanings.50

‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ is a key work in the development of Phaophanit and Oboussier’s collaborative practice. In interviews I conducted with the artists in 2016 and 2017, they link this to an earlier work and ‘moment’ connected to a year spent in temporary residence in Berlin. Atopia 1997/2000/2003 (figs.4 and 5), a series of installations in Berlin in London and an artist book by the same name, also signal the negotiation of internal shifts in their practice and the external perception, or denial, of them as a collaborative artists:

[Oboussier] This is quite an interesting territory. There’s no doubt that the installation pieces were under [Vong’s] name ... But it was shortly after … while we were … in Berlin, that the book was conceptualized. And then there was a hiatus. We relocated to London and things sat for a while, and we decided to formalize our partnership more. I think you’ve identified a key moment for our work where, as Vong said, we were questioning authorship and authority. All that’s solid melts into air is an important part of that, although it was a bit later.

[Phaophanit] Yes, you’ll probably find traces of All that’s solid melts into air in this earlier project [Atopia]; the mapping is there.51

Fig.4

Vong Phaophanit

Atopia 1997 (installation view at DAADGalerie, Berlin,1997)

Polybutadiene rubber, galvanised steel shelving, string

© Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier

Photo courtesy Phaophanit and Oboussier Studio

Fig.5

Vong Phaophanit

Atopia 1997 (installation view at DAADGalerie, Berlin,1997)

Anti-pigeon devices on rooftop

© Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier

Photo courtesy Phaophanit and Oboussier Studio

Although Phaophanit was the formal recipient of The Quiet in the Land residency in 2004 that led to the making of ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’, he and Oboussier travelled together to Luang Prabang. Oboussier was writing while Phaophanit was filming, and the two subsequently worked together on editing the images, texts and voiceover audio. In the 2016 and 2017 interviews, Oboussier reflected that ‘there was … a curatorial expectation that Vong, rather than just being one of the invited artists’, who included Marina Abramović and Janine Antoni among others, ‘was somehow “the Lao one”’. The artists sensed that Oboussier’s presence and informal participation put pressure on this implicit expectation. ‘There was a struggle,’ says Oboussier, ‘as has often been the case. There was a sort of question mark about whether or not I was part of it.’ In 2018 Oboussier noted that their collaboration ‘was unspoken … still in many ways an “undeclared”, tacit one and certainly subterranean in terms of the art world’s narratives’.52

Phaophanit and Oboussier’s collaborative production was not acknowledged by The Quiet in the Land, and Tate continues to attribute ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ solely to Phaophanit.53 In 2023 the artist’s biography on the Tate website was updated to include acknowledgment of Phaophanit and Oboussier’s collaborative practice, with the addition of two sentences: ‘In the mid-1990s, Phaophanit began a collaborative practice with Claire Oboussier. They have since been working as a duo.’54 This amendment, made at the time of the installation of Neon Rice Field in the Duveen Galleries, followed an email from Phaophanit to Alex Farquharson, Director of Tate Britain, ‘pressing for it to be corrected to reflect the reality of our practice’.55 This plea echoes a request made by Phaophanit fourteen years earlier to Stephen Deuchar, who was Director of Tate Britain between 1998 and 2010. The artist asked that Oboussier be acknowledged as writer and collaborator in the exhibition wall text accompanying the display of ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’ at Tate Britain.56 Consequently, the attribution was amended to: ‘A film by Vong Phaophanit, text by Claire Oboussier’. The inconsistences across texts suggests a lack of process or resource to ensure related records are reviewed. Addressing this is key to ensuring such incremental gains – which have required the repeated interventions of the artists – are not lost again.

Tate Interpretations

At the time of writing, no online texts exist for What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten or ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’, apart from what is grimly known as the ‘tombstone data’ usually conveyed on museum object labels. This includes the artist’s name, artwork medium, dimensions, a line on its acquisition or provenance, and the collection reference number. Although the double acquisition of these works may have been strategic for the institution, the fact that they have not been exhibited in fifteen years, or furnished with basic descriptions, means that their representation in the collection online relies on a single image apiece. Tate Gallery records up to 1992 are in the public domain; records from 1993–4 are in the process of being released. The thirty-year backlog means that the display texts produced in 2008 for What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten, and in 2009 for ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’, have yet to be uploaded. At the current rate of progress, will that take another fifteen years? Without strategic commitment to addressing the lacunae and lag in institutional systems and processes, the marginal yet influential texts and documentary ‘scraps’ that evidence or mitigate the museum’s blind spots and biases remain inaccessible. The potential for strategic acquisitions to surface and attend to overlooked artists, artworks, histories and genealogies is repeatedly squandered, while opportunities to interrogate the museum’s systemic oversights, its persistent, problematic and absent narratives, are perpetually delayed.

There is, however, an online collection text available for Neon Rice Field, written by Carmen Juliá, Curator, Contemporary Art, in 2013, at the time of its acquisition.57 Having experienced Neon Rice Field on site in 2023, I revisited the museum’s texts about the work to consider the similarities, continuities and contradictions in relation to my own embodied reading. At a typical length of just over 600 words, the collection text consists of a brief description, a discussion of the materials, quotations from the artist, biographical information and, in some cases, a summary of its exhibitions to date. At less than 100 words, the in-gallery caption produced for the 2023 display affords a sentence each to describing the work, interpreting the rice and neon, discussing the effect and meaning of the materials combined, and providing information about the sourcing of the rice and its processing post-exhibition. The following paragraphs consider the two texts in detail, along with more recent observations by the artists.

Neon

The 2013 collection text introduces Phaophanit’s use of neon as an example of his ‘discreet subversion of the narratives attached to the materials’. The text notes that neon, ‘which could sometimes be assumed to represent the western city, is also a feature of many Asian cities’.58 The 2023 gallery label introduces a modulation, that neons ‘were once associated with Western cities but are now visible across Asia’.59 The recent label is evidently reworked from the earlier text, and seems to insinuate that the ‘East’, once lagging, is now catching up with the ‘West’. The changes between the texts are insubstantial yet the slippages between ‘sometimes’, ‘once’ and ‘now’ avoid historical specificity, universalising the Eurocentric vantage point of the author, which is also presumed of the viewer.

The 2013 text describes the work in relation to the ‘dichotomy between the Western and the Eastern worlds (in this instance, of industry versus agriculture)’.60 Interestingly, the popular association in contemporary Western visual culture of neon with the technologically advanced, futuristic and utopic/dystopic cities of East Asia such as Tokyo, Hong Kong and Shanghai, is not mentioned. The development of pervasive orientalist cultural representations since the late nineteenth century, in which the ‘East’ is projected not only into the past but also into the future through the techno-orientalism of the late twentieth century, is also not discussed.61

Rice

Despite acknowledging that ‘cultural associations’ and ‘cultural allegiances’ might be ‘more complex, more problematic and more fluid than any dualistic reading’, Juliá makes the claim that ‘rice is unequivocally a symbol for the East’.62 Recalling the early reception of the work, the artists state that they ‘have been trying to derail this narrative [since 1993] – it’s astonishing that it still persists’.63 The gallery wall text is slightly more circumspect, employing a less forceful figure of speech that nonetheless reinforces a romantic pastoral narrative, claiming the rice is ‘laid out like a paddy field’. Again, the artists disagree: ‘Is it? This seems like a lazy and culturally stereotypical image or worse … Doesn’t it look more like a ploughed furrowed field?’64 The choice of simile succumbs to the problematic association acknowledged in the following line of the 2023 text, that ‘Rice might stereotypically be considered a symbol for Asia’. It is an improvement, however, to an earlier draft that claimed ‘the artist sees rice as a symbol of Asia’, a statement removed after Phaophanit and Oboussier reviewed the text ahead of the display.65 Their email correspondence with curators, in which they requested changes to the text, demonstrates their careful navigation of institutional processes and sensitivities, and ultimately, relations of power. While the artists emphatically reject the text’s representation of Phaophanit’s views, arguing that ‘the issue is that the artist does not see rice as a symbol of Asia – the work is precisely about making such preconceived ideas vacillate’, they avoid attributing blame to the individual: ‘We did think that the line in question could not have come from you’. It emerges that the artists were caught between the curatorial and interpretation teams, and they are keen to stress that the ‘pushback’ came from the latter.66

The online collection text notes that the artist has ‘in the past used American sponsorship to supply the rice to stage his work’, leaving the geographical, cultural and political significance of its provenance open to interpretation.67 The much shorter gallery label devotes four lines (a third of the available space) to the sourcing of the rice, obtained on this occasion from the food distributor S&B Herba Foods, and its planned processing and distribution to food banks after display. The distributor is one of the UK’s many ‘global foods’ import businesses, established over one hundred years ago, and dedicated to supplying the ‘ethnic foodservice sector’.68 If the former statement alludes to American imperialism and debates around cultural appropriation and authenticity (the USA Rice Council’s aims to ‘Promot[e] U.S.-Grown Rice at Home and Around the World’), can the latter be said to nod obliquely to the trade routes opened up by colonial expansion and the extractive, capitalist relations they serviced?69 Does the label reflect a deal made between the commercial sponsor and museum, the generosity of the sponsor being proportional to the wall space? Or is the concern to anticipate complaints about food waste in view of ongoing world hunger and the ‘cost of living’ crisis closer to home?70 No attention is given to the sourcing of the neon, also from the UK; might this mundane fact dampen some of the impulses to exoticise? In any case, little room remains to attend to the artwork itself.

Field

The 2013 collection text of Neon Rice Field refers to an ‘undulating translucent field’, while the 2023 gallery text amends this to read ‘an undulating paddy field’. This is partially consistent with reviews of the 1993 Turner Prize. The Guardian, for example, referred to ‘gently undulating rice dunes’ and ‘a ploughed field with six red neon strips running up the furrows’.71 As outlined above, it is unclear where or when the culturally specific comparison to a ‘paddy field’ arises. It is evident, however, that the practice of amalgamating existing texts and recycling content results in reductive conflations, dwindling nuance and the perpetuation of problematic readings.

As Corey points out, Oboussier’s essay ‘From Light’ expands on the materiality of rice and neon, how they activate and elevate each other, while Phaophanit has described ‘the olfactory sensations triggered in the room as grains of rice were slowly toasted by the neon’.72 The collection text observes Neon Rice Field’s extension beyond its visible parameters: ‘In addition to the work’s visual impact, the rice also generates its own particular smell, which pervades the space beyond the physical limits of the piece.’ Its multisensory dimensions were underlined in a temporary display in the Duveen Galleries, titled Material as Message, where Neon Rice Field was located in proximity to works by Rachel Whiteread (Untitled (Stairs) 2001, Tate T07939), Lydia Ourahmane (The Third Choir 2014, Tate T16000), Susan Hiller (Monument 1980–1, Tate T06902) and Anya Gallaccio (preserve ‘beauty’ 1991–2023, Tate T11829). The five artists were brought into loose sensory relation, the attendant display panel inviting audiences ‘to look … listen … smell and read’ and ‘become participants’.73 With only thirty to forty words afforded to each artwork, the anonymous author was economical in asserting the effect of the combined materials of rice and neon (‘they create an optical illusion’) and its meaning according to the artist’s intent (‘For the artist, this “third material” symbolises the idea of cultural identity as unfixed and imaginary’).74 Again, it is clear that the lengthier collection text has been referenced yet reduced, undermining the possibility of keeping open what Phaophanit has described as ‘the possibilities of meanings’.75 For Oboussier, the third term in the title, ‘field’, underlines such possibilities, asking ‘And what is a field? It’s an open terrain, isn’t it?’76

In an early interview for the inaugural issue of Frieze, conducted in 1991 as Phaophanit was coming into prominence, the artist explained: ‘[T]he way I work is very personal, very intimate, but I never intend the work to be autobiographical. I’m always trying to find a new platform, where autobiography won’t get in the way.’77 Several years after his Turner Prize nomination, in a publication documenting the Weltkunst Collection at IMMA, Phaophanit insisted: ‘Once you name all the meanings … something still remains, something left over’.78 Nevertheless, thirty years on from the making of Neon Rice Field, impulses to constrain the artwork (and artists) persist. Tate’s past misjudgements and missed opportunities may be attributable to inevitable systemic gaps in museological processes. They also suggest systemic biases in approaches to museum studies, which both reflect and perpetuate deeper ideologies and conflicts. The museum’s readings remain limited by biographical, identity-driven discourses that prioritise and essentialise cultural difference (ironically fixed by a narrative of ‘cultural unfixity’79 ), the recycling of orientalist tropes, and Oboussier’s repeated erasure.80 Without the artists’ repeated interventions, their decades of collaboration would continue to be ignored by the art establishment, despite recognition elsewhere: ‘in the world of public commissions … we are well known as an art partnership … This disconnect is puzzling and frustrating and has proved quite intractable.’81 Phaophanit concludes: ‘as a duo, we are unrepresentable’.82

Neon Rice Field, 2023

The display of Neon Rice Field in the Duveen Galleries as part of the rehang of Tate Britain’s collection displays in 2023 anchors my reflections on the work’s framing over more than thirty years, and underscores questions that are at once timely and overdue. Press coverage of Tate’s first comprehensive rehang in a decade highlighted the prominence of art made by women as evidence of the museum’s commitment to diversifying its collections.83 In the Guardian, Neon Rice Field was central to a passionate, nostalgic lament for the sensations and provocations of British art once epitomised by the Turner Prize:

What happened to Tate Britain? How did it become the kindly killer of everything that was once exciting and dangerous in British art? In the 1990s, this neoclassical building, then just the Tate, was a stage for the new, the home of sensations, a place where provocative art punched you in the face. That era is currently memorialised in the gaping Duveen space in the middle of the museum, where Vong Phaophanit’s eerily beautiful Neon Rice Field, a long dreamy array of rice divided by strips of pink light, points the way to Rachel Whiteread’s towering cast of the underneath of a double staircase. Whiteread and Phaophanit were both nominated for the 1993 Turner prize: the first Turner that had to be seen, in the same way that back then the latest Martin Amis had to be read.84

The critic’s lack of acknowledgement of the casual racism and xenophobia that accompanied Phaophanit’s 1993 nomination is surprising. Tate may have been swift to address ‘British’ as a technicality in terms of the Turner Prize eligibility criteria, but the culturally divisive question of ‘Britishness’ remains as charged as ever. Beyond Tate, the last decade has seen a growing momentum behind anti-racist movements and calls to decolonise, directed at curricula, monuments and the institutions and disciplines by which knowledge is produced and reproduced. The complex histories, legacies and traumas of empire and colonisation embedded in many museums’ foundations are increasingly acknowledged while also frequently swept under a thick and densely woven carpet of ‘uncomfortable pasts’.85 Writing about Tate’s collection rehang, Farquharson stated that it ‘reveals a story of British art that is both national and global. For every major British artist who spent their whole life in Britain, there is another major British artist who was born elsewhere, whose identity is cross-cultural, or whose career had a complex international itinerary.’86 While museums strive towards more ‘inclusive’ and ‘diverse’ representation, and rhetoric shifts towards a more ‘expanded’ and ‘global’ definition of ‘Britishness’, structural barriers continue to perpetuate the lack of diversity in workforces as well as collections. Systemic harms and unequitable relations of power persist through entrenched practices and processes, while dominant discourses of knowledge and value remain largely unchanged.

At Tate, the impetus to broaden and expand the collection has not been matched by a commitment to interrogating the museum’s existing narratives and interpretations. The rate of acquisitions has long outpaced the necessarily slow work of research and interpretation that must inform the fundamental task of description on which collections knowledge is constructed. As the curator Thomas J. Lax argues, ‘recognition of just how the task of description is itself a mode of production might better name our entanglements with the logics of colonialism. We don’t only look after artworks and write narratives about them; we reproduce ideologies scurried away in the category of art, too.’87

Some museums may prefer to hold the institutional tongue (and power) by superficially modifying or modulating their institutional voice. Others may cautiously let go, seeking ways to confront their non-neutrality and to question assumptions of authority with heterogeneous voices and discordant views.88 How to critically engage and contend with a thirty-year backlog that renders the archive inaccessible and opaque? How to reduce the reproduction of harms and shape alternatives to the shallow revisionism and diminishing returns of recycling past texts? There are no shortcuts, human or automated, to ameliorating the vast quantities of existing collection records or generating missing texts.89 What slow, steady, systemic and tactical approaches can be taken now to challenge, interrogate and make more transparent the processes and practices around acquisitions, interpretation and digitisation?

Although Neon Rice Field is no longer on display, the once-in-ten-years collection rehang presented the museum with a judicious opportunity: what if Tate were to commit, over the ten years to come, to prioritising releasing the records of such strategic acquisitions (made in part with the intention of redressing past oversights, only to be overlooked again)? Reconciling the museum collection with its own archive would resurface some of the nuances buried in earlier documentation, and open the works up again. The 1993 Turner Prize catalogue, for example (from which the later collection and caption texts for Neon Rice Field clearly derive), foregrounds location, material, light and themes of memory and time, giving Phaophanit’s relationship to installation and sculptural traditions equal weighting to his personal background.90 Yet the subsequent collection and display texts surrounding Neon Rice Field are increasingly reduced and reductive, the ‘voice of the museum’ faltering with each return. The archive also holds the 2008 display texts for What Falls to the Ground but Can’t be Eaten and ‘All that’s Solid Melts into Air (Karl Marx)’: the former touches on the material, cultural, philosophical, perceptual, sensory and participatory aspects of the work, while the latter credits Oboussier for writing the voiceover, although it stops short of acknowledging the two artists’ wider collaboration.91 The artists have recently contacted Tate again to request that future presentations of Neon Rice Field be attributed to Phaophanit and Oboussier, to no avail as yet: ‘We don’t think the request was refused but nor was it acknowledged or accepted. It was left hanging.’92

The enduring impact of the museum’s marginalia – its ‘minor’ texts and documentary ‘scraps’ encompassing acquisition notes, correspondence, captions, wall texts and object descriptions – should not be underestimated. My close analysis of such short-form texts and fragments relating to Phaophanit and Oboussier’s work has revealed systemic gaps and errors, curatorial confusion, troubling tendencies, as well as complex, forgotten insights. Can their experiences be read as indicative of wider resistances to the individual and institutional work of unlearning, rewriting and re-siting ‘our’ histories?93 Of ‘differencing’ and decolonising ‘the canon’?94 Oboussier has long concluded that ‘the artworld … is fairly disinterested in our collaboration. They’d like to recuperate Vong, because it suits their histories and collections, and it props them up, but my presence – as an “imposter” – makes that harder to navigate.’95 How long can the museum continue with its structures of authenticity, denial and models of recursively generated content, before the collapse of such narratives into meaninglessness?96 What if the museum were to eschew the notion of neutrality, confront its fallacies and contradictions, and embrace not only opinion but speculation and invention? How might those 600, 100 and 40-word limits attend expansively and experimentally to the work, if opened to others (such artists, writers and poets) less beholden to prevailing histories and historiographies?

Re-reading Neon Rice Field

Neon Rice Field is more than a single object, event or moment. The artists consider it ‘part of a series which explores this idea of a simple line of neon that turns into a script and then disappears into a line again’, one of several iterations of works that began with some found fluorescent tubes and a bag of rice in a derelict Amsterdam cellar in the late 1980s.97 The 1993 Turner Prize catalogue reminds us that Phaophanit’s nomination was not only for Neon Rice Field but also for an outdoor work using neon, Litterae Lucentes (figs.6 and 7), in the grounds of Killerton Park, an eighteenth-century National Trust property in Devon. The artist placed nine Laotian words in red neon along the red-brick wall of the kitchen garden, in front of which a grove of bamboo and palm trees had been planted.98 Recalling the relationship between light and bamboo explored two years earlier in What Falls to the Ground but Can’t Be Eaten, here Phaophanit plays with shifts, transpositions and translations: the bamboo, formerly assembled and suspended by the artist, now found; the forest of sound created by children running through the gallery, now a quiet grove; the Laotian script inscribed into a monumental entrance in metal, now rendered in neon.

Fig.6

Vong Phaophanit

Litterae Lucentes 1993

9 Laotian words in clear red neon, installed on a fifty-metre red-brick Victorian garden wall in Killerton Park (National Trust), Devon

© Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier

Photo courtesy Phaophanit and Oboussier Studio

Fig.7

Vong Phaophanit

Litterae Lucentes 1993

9 Laotian words in clear red neon, installed on a fifty-metre red-brick Victorian garden wall in Killerton Park (National Trust), Devon

© Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier

Photo courtesy Phaophanit and Oboussier Studio

In Litterae Lucentes, the neon shines bright and steady in the changing natural light, curling and clinging to the wall like a trailing specimen taking to its new environment, and equally contrived. The historic gardens were designed by John Veitch, whose family went on to build ‘a gardening empire’, employing plant collectors to ‘travel the globe in search for exotic plant specimens, many of which found their way to Killerton’s grounds’.99 The bamboo grove may have been inspired by the ‘wonderfully exotic’ bambouseraie created in 1855 in Languedoc in the south of France (‘the first collection of bamboo plants seen in Europe’), well-known to Phaophanit and Oboussier from many summers in Nîmes.100 Phaophanit’s decision to withhold the translations of the Laotian words in Litterae Lucentes may ‘stress the primacy of the visual’,101 as the curator Simon Wilson notes, but it also brings into relief hierarchies of knowledge and language – the authority of Latin and the dominance of English that was instrumental to apparatus of power across ancient and modern empires, and intrinsic to the ordering of political, cultural and natural worlds. A year after Litterae Lucentes and Neon Rice Field were created, Phaophanit’s installation Line Writing (figs.8 and 9) saw six neon lines rise and curl again into untranslated Laotian script, embedded not into rice but sunk into the very foundations of IMMA’s building, made visible through an exposed section of floor. For Phaophanit, ‘To name … is to possess, to own, to control’.102 However, the titles of works are not intended to name in this sense, but rather contribute to the vacillation of materials and meanings. ‘We try to keep the titles on the edge of meaning’, Oboussier explains, ‘like a trigger … So, Neon Rice Field – it’s a way of setting it free.’103 ‘It also allows space,’ Phaophanit adds, ‘between these two or three words for a weaving through.’104

Fig.8

Vong Phaophanit

Line Writing 1994 (Installation view at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 1994)

Laotian script in six lines of clear red neon

Approx. 7000 x 1500 mm

© Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier

Photo courtesy Phaophanit and Oboussier Studio

Fig.9

Vong Phaophanit

Line Writing 1994 (installation view at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 1994)

Laotian script in six lines of clear red neon

Approx. 7000 x 1500 mm

© Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier

Photo courtesy Phaophanit and Oboussier Studio

Attending to the space between words and materials, then, is key to engaging with Phaophanit and Oboussier’s work. As I have intimated elsewhere and seek to illuminate here, there is ‘room to shuffle, between the materiality of the work, and its immateriality – the invisible and unsaid or unsayable, the “what’s not there”’.105 The ‘conjunction of visual and sonic images’ as described by Corey, and what Oboussier refers to as the ‘conjunction of looking, listening, and reading’ across these works interrupts the politics of identification by which their analyses have been constrained within narratives of ‘Black British’ as well as ‘British art’.106 Continually reconfigured, there are conjunctions of olfactory, vocal and temporal moments across Phaophanit and Oboussier’s practice – in the ambient scents, the seeming silence, the drifting sentiments, the inaccessible voices heard and read, moving between audible and legible registers, sites and spaces interrupted and disturbed.107 In her analysis of ‘All that’s solid melts into air (Karl Marx)’, Corey introduces the concept of ‘passage’ as ‘the passage in and out of language, the passage of time, the passage from page to voice, and the passage of authorship, from one’s voice into another’s’.108 This movement or ‘passage’ continues across sensory, spatial and linguistic borders, from darkness and ‘from light’.109 Language, too, is merely ‘an element, a gesture’.110

Any stability or constant is illusory. Despite the changing formations of Neon Rice Field over time, the work’s collection text declares that it ‘always incorporate[s] seven tons of white rice’.111 If the ‘always’ might imply the symbolic significance of the unchanging volume or number seven that somehow transcends site, this is undermined by the discrepancy of its recent configuration at Tate Britain, where the work was scaled up, incorporating ten tonnes of rice in direct response to the scale of the Duveen Galleries.112 Neon Rice Field was previously presented in solitude, in minimal ‘white cube’-like spaces and laid directly onto the floor. Here it kept cacophonous company. It appeared to hover, as if wilfully defying the gravitational pull and weight of history and power symbolised by its grand neoclassical surroundings, still somehow estranged within its now-home.

Cold mute stones quietly charged by the bright ionised gases encased in glass, lighter than air, grains piled precariously. Neon Rice Field becomes tied temporarily to the place it is installed, yet continues to ‘unfurl … location by location’. As it does, the work’s relation to the site and context from which materials are borrowed, and meanings temporarily made, unravel.113 I opened with senses re-opening, and close with uncertainty unending, embracing that which inevitably escapes and slips, or falls away.

Neon running; light, alighting; taut (untaught); possibilities, intentions (in tension)

Rice pouring, dipping, glowing (a bed, a boat, a wave, a hope…)

Field floating, rising, falling; veins flow, with dreams and discontents.