I am writing this as 2024 comes to a close, in the final weeks of the three-year research project Transforming Collections: Reimagining Art, Nation and Heritage.1 The project is on the verge of slipping into the past tense, but the work is far from over. Braiding art historical and museological research together with participatory interactive machine learning, the project has explored structural inequalities and systemic biases in our national collections and how these might be evidenced and addressed. This introduction provides an overview of the research generated by Transforming Collections by contextualising the articles and interviews included in this issue of Tate Papers, curated by myself as Principal Investigator on the project, and Christopher Griffin, a Co-Investigator and formerly Senior Curator: Research Programmes and Publications at Tate.2 Written in parallel to the institutional account required in the form of a final report to the project’s funder, the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), these words offer an adjacent narrative.3 Once more, with feeling, you might say; and there will be more to say, and do, when minds and bodies are somewhat rested and ready to kick up the dust again.

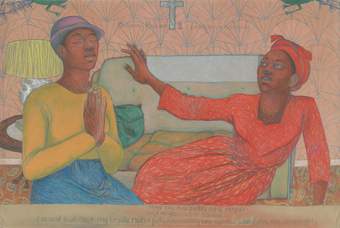

Fig.1

Sonia Boyce

Missionary Position II 1985

Watercolour, pastel and crayon on paper

Support: 1238 × 1830 mm, frame: 1290 × 1878 × 70 mm

Tate T05020

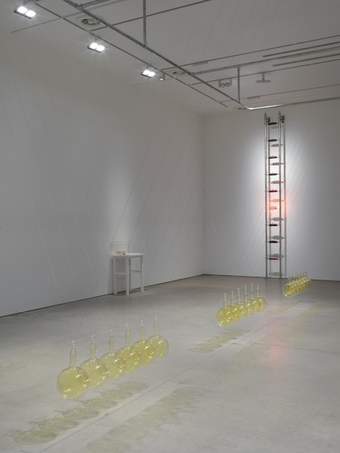

The articles presented in this issue of Tate Papers offer art historical and practice-led case studies that aim to surface bias in collections and, in so doing, resurface marginalised or overlooked artists and artworks at Tate.4 They examine how institutional processes (of acquisition, description and interpretation) write artists and artworks into (or out of) collections, demonstrating how biases can be manifested and harms perpetuated through language, inaccuracies, over-determination, under-analysis, prioritisation, de-prioritisation and erasure. Anjalie Dalal-Clayton puts forward close readings of Tate’s texts on works by Sonia Boyce (fig.1, Tate T05020), Tam Joseph and Keith Piper, evidencing inconsistencies and contingencies in the depth, breadth, limits and possibilities of approaches to Black and brown artists in the museum.5 Andrew Cummings undertakes a critical investigation into the circumstances and correspondences absent from archival records concerning Tate’s acquisition of a work by Hamad Butt (fig.2, Tate T14779), twenty years after the artist’s death in 1994.6 My own essay offers notes towards a micro-art-history, analysing Tate texts relating to the acquisition, attribution and display of works by Vong Phaophanit (and Claire Oboussier).7 It focuses on Phaophanit’s 1993 Turner Prize-nominated Neon Rice Field (fig.3, Tate T14130), whose acquisition into the Tate collection was, like Butt’s, delayed by nearly two decades; it would be a further decade before the work was displayed again. In addition, we present interviews with the artists and practice researchers Evan Ifekoya and Erika Tan, whose work, emerging from residencies undertaken as part of Transforming Collections, activates the hidden connections between artists, archives and collections, invoking alternative genealogies and ancestries.

Fig.2

Hamad Butt

Familiars (‘Cradle’) 1992

Vacuum-sealed glass, chlorine gas

Dimensions variable

Tate T14779

© Jamal Butt

Fig.3

Vong Phaophanit (with Claire Oboussier)

Neon Rice Field 1993

Rice and neon tubes

Displayed: 15000 x 5000 mm

Tate T14130

Although the Tate collection comes under scrutiny for its absences, omissions and errors in this research, examples of more equitable and inclusive practices can be found in the museum’s records and archives. Furthermore, while patterns in artwork acquisitions across museums in the United Kingdom indicate some of the steps taken in recent decades to broaden the representation of artists, histories and practices within collections, expansion alone is not enough. More work is needed for museums and galleries to deepen their understanding of how works come into and are cared for in national collections.8 This requires further institutional investment to address systemic inequalities and inequities in museums and funding structures, where ethical practices are integral to the work of ‘research and innovation’.9 Short-term funded projects that place disproportionate burdens on global majority researchers and practitioners cannot bring about sustainable, long-term change. Such transformation requires a reprioritisation of human relations and institutional processes holistically invested in care, extended to the artists and artworks without which museum and gallery collections would not exist.10 It is with grit and humility that Transforming Collections has sought to enable this work at Tate and beyond. It is perhaps too early to gauge the impact of the project, particularly in the context of wider sector precarities felt through continual cuts and rapid staff turnovers. For now, we can say that our work has led to the ‘rediscovery’ and reconnection of certain artists and artworks across collections; it has enabled critical and reflexive conversations between curatorial and learning programmes across the project partnerships; and it has emboldened colleagues to confront and grapple with the questionable promises and unquestionable challenges of AI in the museum.

Through the publication of these articles and interviews, we aim to demonstrate specific ways in which museums can systematically interrogate their own collections and reconsider their histories and habitual practices, while also giving a sense of the wider research currently being prepared for publication. We want to underline the irreplaceable close, detailed research needed to inform institutional change, and the careful human-driven development essential to any attempt to mobilise machine learning in museums. Against accelerating automating impulses, we hope that others will persevere with us in this necessarily slow work; to acknowledge and share in the critical and often emotional labour entailed in such work; and to mitigate the pressures and constraints that can compromise our ability to enact care. In doing so, let us hold and heed artist and researcher Stephanie Dinkins’s gentle exhortation to shore up ‘our stories, our algorithms’, our data, our ‘future histories’, with feeling and with love.11

Introducing Transforming Collections

Transforming Collections has been a highly ambitious interdisciplinary project, bringing together colleagues across UAL Decolonising Arts Institute, UAL Creative Computing Institute, and Tate as our main partner among fifteen collaborating organisations, with contributions from over thirty collections and archives.12 Our researchers numbered thirty over the three years, including art historians, curators, museum professionals, software engineers and artists. Despite the apparent scale of the project, however, most of these roles have been short-term and fractional, and it is important to acknowledge the precarity and impact of temporary posts and processes on the long-term sustainability of research, researchers and relations. We cannot sustain the work without sustaining the humans. And the work, as I have said, is far from over – a mere ‘moment’ in a longer continuum of overlapping endeavours. Most immediately, Transforming Collections builds on the earlier Black Artists and Modernism (BAM) research project, which ran from 2015 to 2018, led by the artist Sonia Boyce, with myself and the art historian David Dibosa as Co-Investigators.13 Conversations began in late 2019 and continued throughout 2020 as the Tate-led research project Provisional Semantics got underway, funded in the first phase of the Towards a National Collection (TaNC) programme.14 The subsequent TaNC call asked researchers to respond to the challenge of ‘dissolving barriers’, ‘using digital technology to create a unified national collection of the UK’s museums, libraries, galleries and archives’.15 The very framing of the call raised fundamental questions around spoken and unspoken divides, and the notions and ideals on which ‘nations’ and ‘collections’ are founded.

Twenty-five years ago, Stuart Hall voiced a question that remains pertinent and contentious: ‘Whose heritage?’16 These past projects, among others, can be said to share disruptive, anti-racist, counter-canonical, restorative and reparative impulses. Transforming Collections developed amid debates around ‘contested heritage’, which both intensified and paled in the contexts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement and ongoing eruptions of anti-Black, anti-brown and anti-Asian violence. As some persist in stoking and inflaming the so-called ‘culture wars’, others persevere in the long-term battles to acknowledge and address the enduring harms of empire and colonisation.17 And while these endeavours may be slow and exhausting (even more so when the outlook seems depressing or pessimistic), it is essential that we make space, somehow, for the small and playful – even joyous – acts of resistance and reclamation needed, to re-imagine our past and future histories.

Transforming Collections examined how – structurally, systemically, persistently and problematically – we come to know or forget certain artists and artworks, particularly those identified as and attributed to global majority ethnically minoritised makers. Whose voices, bodies and experiences are centred and privileged within collections? How can the architectures, algorithms and relations of power and oppression that structure and define collections’ narratives be surfaced and transformed? And what could an equitable, inclusive, distributed yet connected, heterogeneous and evolving ‘national collection’ look like?

In 2016 an audit of just over thirty public art collections in the UK, conducted as part of the BAM project, produced an indicative snapshot of works acquired since 1900 by artists identified as Black, which the BAM researchers defined as artists with African, Caribbean, Asian or MENA-region (Middle East and North Africa) heritage.18 Such works made up between less than 1% and 4% of collections. In 2022 an extended and expanded audit as part of Transforming Collections found that the proportion had increased, marginally, to just under 5%.19 Such broad, indicative quantitative data lends itself to potential misuse if the contexts of acquisition and interpretation, and the parameters of associated metadata, are not critically interrogated. It has therefore been essential to analyse and contextualise this data with nuanced qualitative research into analogue archival as well as digital records and, where possible, with the collaboration of the artists themselves.

When an artist, maker, work or object is persistently identified in racialised, ethnicised, gendered, sexualised, exoticised, orientalised, heteronormative or ableist terms, or defined in negative relation as ‘non’-white, ‘non’-European, ‘non’-Western, we have to ask: whose world and worldview remain centred? Whose knowledge, whose standards, remain normalised? Working with the invariably incomplete, sometimes chaotic, disparate and messy data, project researchers undertook close critical readings of texts, including catalogue entries, wall panels, display captions, acquisition notes, policy documents, correspondence and interviews. From these, we formulated a series of case studies and historiographies of works in the Tate collection and other collections. The studies investigate the tropes and mechanisms of differencing and othering, not only where these are blatant but also where they may appear to be innocuous or benign. Those that lie beyond the scope of the articles and interviews presented here include Alice Correia’s examination of the acquisition and interpretation of artworks by artists of South Asian heritage, and Tehmina Goskar’s analyses of ‘patterns of patronage’.

Fig.4

F.N. Souza

Crucifixion 1959

Oil paint on board

Support: 1831 x 1220 mm, frame: 1952 x 1341 x 65 mm

Tate T06776

Fig.5

‘Museum x Machine x Me’ Late at Tate Britain, London, 4 October 2024

Photo © Tate (Guillaume Valli)

Correia’s research focuses on F.N. Souza, Avinash Chandra and Gurminder Sikand. She offers a close critical reading of the internal and public-facing interpretive information written by Tate curators between 1993 and 2022 about Souza’s painting Crucifixion 1959 (figs.4 and 5, Tate T06776), exposing Eurocentric biases, errors and omissions in how his career and artistic reference points were perceived and presented. Her audit of works by Chandra in public collections reveals the importance of the art historian W.G. Archer to the artist’s career. Keeper of the ‘India Section’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, from 1949 to 1959, Archer rooted Chandra’s work within a particular South Asian framing that has had ramifications for how the artist’s work is positioned and interpreted today. Correia also considers the purchase of eight paintings by Sikand by six public collections in the Midlands and northern England during her lifetime, and argues for the significance of ‘the regions’ to Sikand’s practice within the narrative of British art.

Meanwhile, Goskar looks at the audit data on 3,767 artworks, identifying 41 types of acquisition from 321 distinct expressions. If the architecture of museum documentation is designed to forget or obscure the networks and negotiations between museum, artist, curator, donor, sponsor and funder, then the dataset of ‘gifts’ and ‘gift-like exchanges’ (which account for 24% of acquisitions with nearly 10% being direct gifts from artist to museum) surfaces latent systems and relations of power. Goskar analyses the mechanics and relationships by which artworks by racialised artists enter public collections and the contextual histories of specific acquisition processes and impulses.20 Experimenting with the project’s interactive machine learning prototype using training datasets drawn from approximately 10,000 excerpts of texts,21 Goskar combines human–computer interaction and cultural analysis to identify changes in language use. Her findings point to the ways in which notions of benevolence and equity can occlude the mechanisms and relationships that underpin acquisitions and collections development.22

Evidently, ‘transforming’ entails more than questions of representation. It requires us to ask not only ‘how many’ but also to interrogate how we ‘count’ or are counted (in the sense of how we see/are seen, regarded, validated and esteemed, or not). Who is in these collections? What has been collected, and why? What are the historical and contemporary connections, networks and relations that have led to the nomination, selection, acquisition, exclusion or rejection of particular works and objects? On what terms have they been funded, donated, accepted or declined? Who sits on which panels? What is, or is not, recorded in these processes? How, subsequently, have artists, makers, works and objects been named, framed, classified and described? Who, and what, is cared for, or conversely, neglected?

Transforming Tate?

Such questions are necessarily amplified and magnified at Tate, as home to and custodian of ‘the national collection of British art from 1500 to the present day’.23 In 2019 Tate published its Research Strategy, which set ambitions to research the ‘uncomfortable histories’ behind and within the collection, coinciding with broader institutional recognition of the ways in which the museum – and indeed the museum sector – needed to change to do justice to the artists and histories that it had neglected for so long.24 Over the last five years, the museum’s vision and annual reviews have emphasised histories that are more ‘interconnected’, ‘transnational’, ‘multiple’ and ‘global’, more ‘diverse’, ‘balanced’, ‘pluralistic’ and ‘representative’.25 Within their combined 185 pages, three sentences speak directly to Britain’s imperial past: we are told that ‘institutions are taking responsibility for unlocking histories of empire and colonialism embedded in their works’;26 displays at Tate Liverpool ‘will feature work from beyond Europe and North America, especially where there are historic relationships with Liverpool’, thus providing ‘the opportunity to forge new thinking around colonialism and decolonisation’;27 and, less directly, that ‘texts and captions for artworks will be reviewed and amended to correct underrepresentation in the histories described’.28 In 2022 Tate updated its Research Strategy, with thematic priorities including ‘[p]rogressing museum practices and histories’ and ‘contemporary concerns including decoloniality, representation, diversity and identity politics; their impact on art museum collections, practices, structures and audiences’.29

The project informed an internal review by Tate’s Research and Interpretation departments of the ways descriptive terms are applied to collection items during the acquisition and cataloguing process. Tate colleagues surveyed and consolidated existing collection information known to perpetuate bias, including critical commentaries from staff and audiences (for example, in the form of offensive or euphemistic language, or the under- or misrepresentation of identities). They analysed editorial approaches within collection texts (for example, catalogue entries and gallery display captions) to begin addressing instances of discrimination. Tate’s Digital team mapped the complex departments and systems implicated in the production of cultural knowledge and management of collections information. They scrutinised the infrastructures that determine how Tate makes discoverable 150,000 collection items online, which linked data through an inconsistent process called ‘subject index tagging’ first introduced over twenty years ago, and analysed the risks therein of reproducing biases and perpetuating harms.

Fig.6

Keith Piper

Viva Voce 2024 (film still)

Two-channel video installation

21 min 40 sec

Tate Britain, London

© Keith Piper

Tate’s ongoing work on its digital content reflects some of the measures taken to address audiences’ experiences of the collection online, while the museum continues to consider remediation work on collection texts. The subject index tags were removed from the website as part of a redesign in 2024. While the Transforming Collection project’s research highlights some of these complexities and consequences, the case studies also attend to wider questions of authorship, ownership and responsibility, including Tate’s handling of the controversy around the Rex Whistler mural and subsequent commissioning of a new artwork by Keith Piper (fig.6).30 The long-term impacts of Tate’s engagement with Transforming Collections remain to be seen. With its considerable influence on national, and international, narratives, it will be interesting to see how Tate demonstrates its strategic commitment to the necessary, radical and rigorous work of institutional change into the future, with care.

Museums x Machine Learning

Transforming Collections has been structured by a collaborative, interdisciplinary, braided approach, interweaving art historical and museological inquiry with interactive machine learning (ML) development. Importantly, it is the former that has driven the latter within the project, and not the other way round. Could ML help us to surface and evidence patterns of bias in collections? To resurface artists and artworks? Steered by researchers’ questions and collection partners’ needs, an ML tool has been iteratively developed, co-designed and refined to support the analyses of collection data.31 It cannot correct the biases or errors in texts, or fill gaps in collections, but it can help us look critically at what is, and is not, there. This iterative process has been uneasy, at turns frustrating, revealing and inspiring, requiring the mutual interrogation of ‘common sense’ knowledge and assumptions; ‘interdisciplinary collaboration’ is much easier to say than to do.

Against the backdrop of accelerating AI technologies, our approach has been deliberately slow. Deliberating and slowing down, mindful of the risks of multiplying harms, we have taken time to grapple with our individual and disciplinary habits and biases (we are still grappling), to understand the limits of what ML can and cannot, or should not, do. From the standpoint that technical ‘solutions’ are neither desirable nor sufficient in overcoming barriers that are social, cultural, historical and ideological, the critical analytical tool, or CAT, must be deployed with caution, as a spanner in the works.

The ML CAT can slow down habitual workings and clarify thinking. It can enable cross-search and research into small bespoke datasets to support the question or task at hand. For example, a researcher may train the tool to discern the presence of inaccessible language, colonial ideology or orientalist rhetoric in museum interpretation; another may teach it to highlight examples of figures that appear in artworks yet are unnamed or unacknowledged in associated texts. In the process of testing and refining the tool with our partners and collaborators, Art UK were interested to uncover the prevalence of jargon or specialist language, while Andrew Cummings used the ML to identify the underlying orientalist ideology informing interpretations of work by Kim Lim and others. At the ’Museum x Machine x Me’ conference, held at Tate Modern in October 2024, the project researcher Jon Gillick demonstrated how AI’s blindspots – such as an inability to detect a Black figure in a painting also depicting a white woman and a dog – directly reflects the knowledge, ignorance and biases of the ‘human in the loop’ (which humans?). The consequential risks and cumulative harms of dehumanisation, hyper-sexualisation and erasure have been powerfully explored by Dinkins in her artistic and social experimentations with ML over the last decade, from early searches using the phrases, ‘a ___ woman smiling’ (fig.7) and ‘a Black woman crying’ to the AI.Assembly, a series of public conversations that ask, ‘What does AI need from you?’32

Fig.7

Presentation by Stephanie Dinkins at the ‘Museum x Machine x Me’ conference, Tate Modern, London, 2–3 October 2024

Photo © Tate (Josh Croll)

As the tool has evolved, so has its name, from spanner, to analyser, to CAT. Now available as an open-source application, the optimistic ‘Collections Transformer’ comes with caveats and cautions: it is not a magic wand, makeover tool or stain remover. It will not clean up the mess, remove the offense or undo the harm enacted by museums. Building and training the ML CAT requires careful modelling, testing and refining for each task; it is an experimental and considerably time-consuming process that reflects back to the user their assumptions, biases, choices and expectations. It might better read the signs and symptoms of ‘health’ and harm, expand the scope of inquiry and proffer unexpected glimpses of other pasts and lives, but it cannot automate the deep work of analysis and change itself.33 How ‘good’ or ‘bad’, ‘useful’ or otherwise the tool proves to be, depends on the individual who engages with it. Judicious use of the Collections Transformer requires the unlearning of normalised expectations, a rewiring of human and machine. We know that ‘museums are not neutral’ – we must remember that neither are machines, and nor are we.34 Can we teach the machine to learn in order to help us unlearn? It is worth persevering and persisting in this endeavour for the possible returns, over time; of potential and future histories.35

Museum x Machine x Me

The 2024 'Museum x Machine x Me' programme was a week-long collaborative public event across Tate Modern and Tate Britain, marking the culmination of the Transforming Collections project.36 The programme title underlined questions of power, agency and responsibility at the intersection of institutions, technologies and individuals. Developed and curated with Tate Learning to activate the themes, methods, findings and emerging outputs of the project, the programme sought to foreground wider cross-disciplinary and intergenerational communities of creative practice.

At the centre of the programme was a two-day conference at Tate Modern, which opened with a keynote conversation between the artists and academics Stephanie Dinkins and Roopika Risam, moderated by the curator and researcher Ramon Amaro.37 Dinkins spoke about her use of emerging technologies and social collaboration to work towards technological ecosystems based on care and social equity. Her experiments with AI have led to a deep interest in how algorithmic systems impact communities of colour and the conclusion that ‘our stories are our algorithms’. She asks, ‘What does AI need from us?’ to ensure these stories and algorithms are indeed ours?38 In response, Risam spoke to the multiple iterations of ‘me’ implied in machine learning in museums. Her research on the entangled historical relationship between museum data and colonialism highlights its ongoing impact on cultural heritage data today. She argues that if our positionalities inevitably influence ML methods, then starting at ‘me’ is essential to transforming museum collections with machines: ‘the “me” of cultural heritage professionals, the “me” who is represented within collections, and the “me” who is excluded by them’.39

What do museums ‘want’, in the doubled sense of desire and lack? Introduced by the academic Ewa Luger, with the project researchers Mick Grierson, Rebecca Fiebrink, Jon Gillick and Ananda Rutherford, the first conference session outlined the challenges and collaborative, interdisciplinary approaches negotiated within the project; the testing and contesting of assumptions and expectations; and the iterative development of an ML tool whose critical, analytical potential in museums can only be realised through responsible, ethical application by its users: the ‘you’ or ‘me’ in the equation. This was followed by the session ‘Please Give Generously’, chaired by Christopher Griffin, which brought into conversation the curator and cultural historian Tehmina Goskar, the arts professional Melanie Keen and the sociologist Alexandre White, on what, and how, collections ‘keep’. From ‘keeping’ to ‘caring’, how do changing political, policy and economic landscapes impact the practices and ethos of collections? How does the language of benevolence and gift-giving reveal or obscure relations of power? What institutional and curatorial strategies might be mobilised to address uncomfortable legacies and suppressed histories? How can museums practice equity and ‘generosity’ in a sector facing ever-greater scarcity, to redress, restore and potentially ‘give back’?

Fig.8

‘Museum x Machine x Me’ Late at Tate Britain, London, 4 October 2024

Photo © Tate (Guillaume Valli)

Fig.9

‘Museum x Machine x Me’ Late at Tate Britain, London, 4 October 2024

Photo © Tate (Guillaume Valli)

Moving from institutional frameworks to individual case studies, the curator and writer Elinor Morgan introduced the art historians Anjalie Dalal-Clayton, Alice Correia and Andrew Cummings, who shared insights into their research on the artists Tam Joseph, Sonia Boyce, Keith Piper, F.N. Souza, Avinash Chandra, Gurminder Sikand, Hamad Butt and David Medalla, among others. Their presentations sought to surface the limiting tendencies, errors and contradictions around the acquisitions and interpretations of the artists’ work, while also pointing to possibilities for looking, reading and writing otherwise.40 The conference closed with a final session chaired by David Dibosa, bringing myself and the artist and researcher Charl Landvreugd into conversation. We spoke to our positionalities in relation to British and Dutch colonial histories, traversing disciplines. Together we ruminated on how collections and archives are mutually constituted, entangled and imbricated, in ‘national’ (and ‘international’) narratives; how we might attend to the multitudes of unheard voices, within and without museums; and how artists, ourselves included, attempt to speak out, speak back, sound off and sound out their presence and potential, through serious and playful acts of interruption, disruption, reinvention and devotion, as forms of resistance.

Hands-on workshops led by Jon Gillick and the data scientist Polo Sologub at Tate Modern and Tate Britain introduced visitors to the Collections Transformer. The engagement and feedback suggest the real-world usability of the Collections Transformer. The Tate Late event at Tate Britain featured numerous pop-up talks and archival displays in the galleries (fig.8) and library spaces (fig.9). These were led by project researchers including Ian Sargeant in conversation with the artist and activist Hardish Virk on artists’ archives outside the museum, and the artist Keith Piper in conversation with Dalal-Clayton about his Tate commission responding to the controversial Rex Whistler mural.41 Performances, activations and interventions, including by the design studio Hyphen Labs, the artists Karen Palmer and Gary Stewart, the archivist Kaitlene Koranteng and the research studio Electronic Life, expanded contexts and communities of practice and research. Importantly, the Late shifted and multiplied the modes and dynamics of engagement, from ‘speaking to’ through to more intimate and immersive forms of ‘speaking with’, while also emphasising the importance of embodied, affective encounters, in physical proximity to artworks and archives, whose material traces and excesses cannot always be contained.42

Fig.10

Christina Peake

The Faith, Spirits and Testimonies of Granny Lowe and the Bajan Sea 2024 (installation view, South Tanks, Tate Modern, London, 2024)

© Christina Peake

Photo © Tate (Ariel Haviland)

It is arguably the experimental explorations of artists as practice researchers that most effectively, and affectively, interrogate such questions. The work of the four practice researchers engaged in Transforming Collections, which was displayed at Tate Modern from 2–6 October 2024, explored the normalised, limiting, harmful or careless narratives produced by museums to critically reimagine our collections and heritages. Evan Ifekoya turned the hard, cold shell of an unoccupied gallery space into a series of soft, warm zones for encountering the artist Maud Sulter in ‘an act of digital devotion’. Ifekoya invited contemporary artists to step into dialogue with the legacy of Sulter’s work with an audio-guided website as virtual shrine, personal archival materials, a reading room and a screening. In the Tanks, Christina Peake sculpted a coral-like island out of the concrete floor (fig.10), which carried several objects aloft as if washed up or salvaged from marine environments. Animated by underwater footage and accompanied by intimate, speculative narratives, each story called forth the spirits of their originary communities and cosmologies.

Fig.11

Yu-Chen Wang

How We Are Where We Are 2024 (installation view, South Tanks, Tate Modern, London, 2024)

© Yu-Chen Wang

Photo © Tate (Ariel Haviland)

Yu-Chen Wang re-presented the visual tropes of the nineteenth-century museum as a theatre set or group of props (fig.11). In so doing they evoked the pursuit of ‘beauty’ in art and architecture intended ‘to rectify the moral and physical ugliness of industrial capitalism’,43 and diverted attention away from its violent racial, colonial foundations. Erika Tan assembled an array of sonic and visual elements, supported by temporary structures made from materials reclaimed from Tate’s store. Seeking to ‘sound out’ the data on items relating to Southeast Asia from the Tate and Wellcome collections (traversing art and medical histories), Tan fed this through a ‘Diagnostic Instrument’ made from fragments of instruments collected from the region by her mother. Tan calls the work ‘an interrogation into the depths of museum collections’, ‘states of “health and wellbeing”’ and ‘a search for kinship’.44

These myriad interventions transformed the museum: its spaces and artworks differently enlivened, its audiences differently embodied with the voices and experiences of others. They re-centred, re-sensed, re-sounded other stories, hinting at what the museum could become. To ensure such transformations are embedded in equitable and sustainable change that recognises and empowers us fully as humans, we all need to ask: what does the museum and machine need from ‘me’? What happens if/when the global majority ‘we’ (as artists, academics, museum workers and audiences) choose not to identify or be identified, choose not to represent or be represented, refuse our reductive marginalisations and minoritisations? We have, and continue, to disappear… How can we refuse these erasures, reappear and reassert our individual and collective stories, our past and future ancestries, our voices and multitudes, otherwise?