The Transforming Collections practice researcher in residence programme invited four artists to develop artworks that explore ‘how museums collect and care for collections, how people, artworks and objects gain or lose recognition, and the potential role of new technologies in unearthing these stories’.1 Ifekoya’s artistic contribution, Ancestor as Muse (figs.1–2), takes the form of a ‘website as virtual shrine’ devoted to the artist Maud Sulter (1960–2008).2 They also presented an archival display and film screening at Tate Modern in October 2024 as part of the Museum x Machine x Me public programme.3 In their artist’s statement, Ifekoya describes their approach to the project:

Accessing the work of Maud Sulter held in UK national collections presents an incomplete picture. Instead, I look to archives and those inspired by her prolific practice and organising to understand its breadth. My intention is to reimagine a collection as an intimate encounter with Sulter’s practice and her long-standing legacy and impact. Taking the Zabat series as a starting point, I considered how Sulter’s work is framed and taught, and the varying degrees of accuracy of information shared about her online.4

Fig.1

Evan Ifekoya

Ancestor as Muse 2024, screenshot of homepage

Digital artwork

https://www.ancestorasmuse.com/

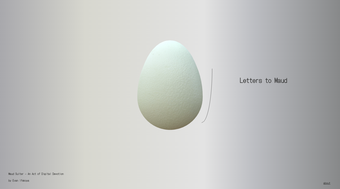

Fig.2

Evan Ifekoya

Ancestor as Muse 2024, screenshot from ‘Letters to Maud’

Digital artwork

https://www.ancestorasmuse.com/

Christopher Griffin: Let’s start at the beginning by reflecting on your initial interest in the Transforming Collections project, its research questions and ambitions. What was it about the project that made you apply for this research residency?

Evan Ifekoya: I arrived already being an artist who works with archives, who also works with other artists’ work. I’ve been in dialogue with Maud Sulter’s work, with Lubaina Himid’s Making Histories Visible archive – there’s been other people’s work over the years that I’ve been in dialogue with and with their archives, as an artist. Not only in a show like Ritual Without Belief, but also in my collective organising as part of groups like Collective Creativity, where we’d also do archival research together.5 So I was curious about this idea of intervening into a national collection as an artistic research process, because it was something that I’d already been thinking about but hadn’t necessarily articulated. It was just a part of my practice. I was interested in what it meant to zoom in on that aspect in particular.

And then in terms of the machine learning aspect, yet again that for me was a curiosity. I hadn’t really worked with it within my own practice. I’d been part of a project called New Mystics which involved working with ChatGPT and another text-based AI that I’m forgetting the name of.6 Myself and the person who runs the project, Alice Bucknell, did an interview. She interviewed me, she then fed the transcript to this AI that then created a new text based on our interviews. I was really curious about that slippage between the moments where it felt really clearly like my voice and then moments where it became the voice of people I’d mentioned. And I was interested in what it means to craft and shape text in dialogue with AI, with technology that is learning from us, in this kind of back-and-forth relationship. And there are also things that are unknown about this technology and what it means to work with it. That, for me, also raised some curiosities, and was something that I wanted to think about. What would it mean for that to become part of my own research process? Initially, I definitely saw it as something I would utilise to create something text-based, but in the end, I took it in some other directions, which is great.

Christopher Griffin: That work made with Alice Bucknell, and the way that the AI software adopted your voice, was mind-blowing to me when I first heard you talk about it! It’s a great example of exactly the kind of exploration that this project is also trying to undertake in relation to identity and authenticity, but I think also chimes with your interest in the affinities you share with other, older artists, other voices and how you form connections with them or collaborate with them that – like with the AI interview – reflects on, plays with or extends versions of yourself. In this way, your use of artists’ archives and the material they hold offers a more creative counterpoint to the desk-based research undertaken by art historians on the project who are exploring the same or similar archives.

Evan Ifekoya: There are two things that came into it for me as an artist: this idea of intimacy and the relationship to the material and the collection. Drawing on my experiences of working with collections or with archives, I didn’t want to just reproduce that kind of coldness in how I work with or present archival material, but really think about this material as something that is close. In my application, I talked about something that Maud Sulter had written where she talks about the ‘saphie’ and this idea of visitors to her show taking little tokens of remembrance, literally taking physical parts of the work. Her really relating to that and really identifying with that. And I wondered what it could mean to think through that.

AI and questions around intimacy and affinities and solidarity and closeness and proximity, they’re all things that I’m thinking about, and how that shapes the experience with the work, because there is no neutral experience. We don’t come into things neutrally, even if that might be how something is presented. There’s always some kind of level of engagement or proximity we are supposed to have with the thing, based on how that space usually operates. And so I’m interested in pushing against that or thinking about that more intentionally.

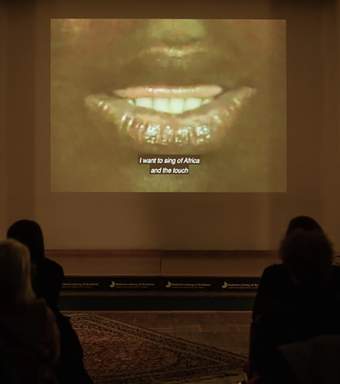

Fig.3

Natasha Thembiso Ruwona (dir.) and Tomiwa Folorunso (prod.)

maud. 2022 (Installation view, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2022.

Photo © Najma Abukar

Christopher Griffin: I think what you alluded to about archives and other collections held within institutions – you used the word ‘coldness’ – is really important, because it’s not neutral, like you say. Given that institutional collections and their practices form the subject of this research project, I’m curious to know how you create the intimacy that you describe when undertaking research within and about institutions.

Evan Ifekoya: It is tricky. You know, when you’re navigating these spaces, because they do have their own rules around how you can interact with the materials. In terms of when I’m in those spaces, it’s hard to intervene in that moment. But what I do take away with me is a kind of record of the experience and ideas about creating or holding a space. To share something of these materials or these artists or this practice, what is the kind of space that I would want to create? Those questions have definitely been what I’m exploring for my final project, which is in two parts: the website and then also wanting to hold the space for this Maud Sulter film made by some younger artists, which I learnt about as part of my research (fig.3). Becoming in dialogue with them and their project has also become a really important part of the work.

Christopher Griffin: So the environment you’re creating as part of your work on this project is intended to offer a counterpoint to the kinds of institutionalised spaces where archival material is usually accessed? A more intimate, softer, warmer space, in contrast to the ‘coldness’ of the institution?

Evan Ifekoya: Yeah, for sure. It is intentional because it is reflecting on the experiences that I’ve had, and not wanting to reproduce them, but wanting at the same time to share that material with people in some way. Those spaces, they have their own rules, so what does it mean for me to intervene with this material? And what are the ways that I want to do things differently, and make a different kind of space available? What is it that I can harness in this moment to make more visible or make more space for? For me, there is a lot of intention about what the space can or should do, and for multiple reasons. One is that the outcome is now so focused solely on Maud Sulter’s work and I feel like I’m taking on a kind of responsibility to speak for and with her practice, so actually paying it respect and reverence is very important to me. Not only am I thinking ‘what is it that I want to get out of this experience?’ But I’m also thinking ‘is this a way that Maud would want the work to be exposed?’ A lot of folks who are, like you say, on the desk working with an artist’s material, they’re not thinking ‘oh, how does the artist want the work to be framed?’ I am thinking about that. ‘Is this in alignment with the artist?’ I’m taking on that position as I think about what it means to present what this work will eventually be.

Christopher Griffin: This is a good moment to maybe focus on your long-standing interest in Maud Sulter, her art and her advocacy. How would you describe your interest in her and her work? And how does the work you’re creating now reflect your relationship to her?

Evan Ifekoya: It’s funny because, as part of this project and as part of developing the website, I’ve been really thinking about the relationship with Maud, because actually I’m also using the website not just to share what I can of the material that exists, but also to map my own relationship with her through the letters that I’m sharing as a kind of audio guide. Maud was somebody who I first discovered while I was at university. Later, getting to connect with artists like Lubaina Himid and Sonia Boyce, I learned about the role that she played in this wider Black arts movement. It wasn’t just her art, but it was also her activism and her commitment to holding space and making space for other people’s practices that I became also really inspired by. I’ve done a lot of research already in the Making Histories Visible archive, which unfortunately I think is no longer accessible. There’ve been opportunities to research and study her practice in archives but then also just to learn from people who knew her. She wasn’t afraid to speak her mind. When I got to go to the Rochdale archives as part of this project, I was reading the letters that she wrote and her correspondence. And she wasn’t afraid to let curators know that they need to get their shit together. Stuff like that has been really encouraging for me in my own practice and it’s become part of my own work to then continue to share some of that, so that Maud’s work can continue to live on through the people who have been impacted by her.

Christopher Griffin: Would you say that the ambitions you describe – to bring people together, to commune, to facilitate exchange – have become part of your artistic practice? That this kind of curatorial work is part and parcel of your work as an artist?

Evan Ifekoya: Yeah. And it’s interesting because it’s only really in the last couple of years that I’ve really begun to see that. Holding space for bringing groups together, collective organising like with Collective Creativity, with Black Obsidian Sound System…7 I remember even years and years ago, in one of my first jobs after uni, working in the Tate bookshop around 2010 or 2011, I organised a monthly crit club, because there were so many artists that worked at Tate. I even got a bit of funding and would invite guest artists to chair the discussion. Even when I was on my BA, we would stage self-organised shows. And so I think there’s some kind of urge within me that is driven to organise collectively and make space for conversation, discourse as practice. And that’s why also holding the space for this screening and this conversation, which will then also become a part of the website, feels really important as well as another way of acknowledging this aspect of my way of working.

Christopher Griffin: Thinking more about your practice as a researcher, how would you describe your working processes? What have you learned about your research practice over the course of this residency in particular?

Evan Ifekoya: Coming into this, I actually hadn’t ever been to Rochdale. I hadn’t ever worked with the archive there. There’s a lot of material around Maud. So very early on I was like, okay, I need to go to Rochdale. Coincidentally, there was the show that Alice [Correia] had curated, so I was able to organise a trip where I went up for that and spent a couple of days in the archive there.8 It was a challenging space to navigate because it was literally very cold in that archive, and you have this table and these kind of stiff chairs. And it made me wonder, ‘what could a different kind of encounter with this material look like?’ So I definitely had that in mind as well, after that experience.

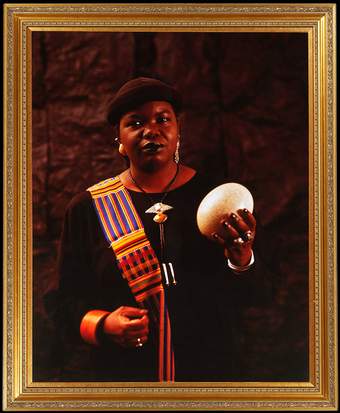

Fig.4

Maud Sulter

Polyhymnia (portrait of Dr Ysaye Barnwell) 1989

Photograph

Photograph approx: 1280 x 1020 mm;

frame: 1400 x 1160 x 450 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

I was also really interested in thinking more about Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s work. I think actually it was you, when you shared the [Tate] materials around Rotimi. What was curious for me was how there were these redactions and absences. With Rochdale, I felt like I got so much closer to Maud, whereas with navigating the Tate archive, I felt actually more distance, in terms of what I was able to glean, what was publicly available in terms of the material. That was when I decided I was going to focus more on Maud, because I just felt like there were more ways I could go into her material.

I became very focused on the Zabat series. I was curious about one photograph in particular, Polyhymnia (fig.4), and how the egg hadn’t really been discussed. There’s one reference where it’s briefly mentioned, and then Maud responds. I was also at that point starting to think about the machine learning aspect and working with Midjourney, which is an image-based program. I became really interested in prompt crafting. With prompt crafting, you can either input text and then it generates an image or you can input images and then it’ll create new images. So I was inputting Maud’s work. I think at that point I was inputting Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s work too. I was also describing their works myself and then inputting text, and creating environments that I wanted the work to exist in, thinking about the spatial in relation to the sonic. Very early on my question was about unravelling or speaking to the spiritual dimensions of these artists’ work, which felt under-explored or underrepresented. So I was thinking very much around a sonic environment that could speak to this spiritual dimension. A lot of my sonic explorations were around that, thinking about elemental sounds. Thinking about ritual, which again is already part of my practice.

Through that I found out about the Maud film and I’d been in dialogue with those folks. And then I decided I really want to show this film in London. There’s also this book that they made. Making space for that just felt like such a great way to be in dialogue with Maud’s legacy: her body of work, but also how she’s impacting the present, and how her work continues to speak into the future. I didn’t want to just see it as this historical thing, to look at her work from the past, but instead to be in dialogue with people thinking through her now, and who are inspired by her now, and are making work about her now.

Christopher Griffin: You mentioned the film about Maud that will be shown as part of your presentation. Am I right in thinking that one of the filmmakers first learned about Maud from you, when you gave a talk about her in Glasgow that they attended? So in many ways you were the catalyst for the creation of the film, as well as now supporting its circulation by screening it within your own work. Again, you’ve created a really beautiful cyclical relation with other artists, this time younger artists, but with Maud in the middle, as though you’re all orbiting her and learning from each other, through her.

Evan Ifekoya: Yeah. I did a video call with Natasha [Ruwona, the director] and that’s when she shared that she first heard about Maud through a talk that I did in Glasgow with Collective Creativity. To have played a small part in the genesis of the film was also really encouraging. To know that this work of continuing to speak her name, to speak her work, her life – there is a ripple effect happening, and that was really encouraging in terms of thinking about this website, what role it could play as a resource for people, as a tool for people. That’s definitely what I hope it will become.

Christopher Griffin: It’s clear from what you’ve described that so many distinct aspects of your practice all seem to be coming together in unison in this new work. I’m curious to know what this opportunity has allowed you to do differently. Has bringing different parts of your practice together allowed you to see it or make sense of it in new ways?

Evan Ifekoya: It’s provided this opportunity to crystallise things that had previously been disparate ways of working for me. There are definitely things that continue: this idea of an intimate experience with something, or making things more accessible, or inviting the viewer to be an agent. But this idea of it happening within a virtual space, that is new. A new way of thinking through spatial politics or sonic architecture: what does it mean to do that in a virtual realm? That is definitely a new enquiry for me, one that feels very much out of my comfort zone, to be honest. It very much requires me to entrust a lot of the creative and conceptual ideas to somebody else to be in dialogue with, because there’s limits to what I can do. But then at the same time, inviting a web designer in means that these ideas can be realised in a way that I could never have been able to imagine before, which is really exciting.

Christopher Griffin: You used the word ‘slippage’ earlier in relation to the way your own voice melded into the AI voice, and I was just thinking about how you create environments without friction, despite being made of different component parts, and the sense of fluidity that is engendered by your work, which I know is very deliberate. How do you intend to replicate this digitally in the online spaces that you are creating for this new work?

Evan Ifekoya: Thank you for mirroring that back. That is, I guess, the other question for me that I am most curious about: how does this experience that I seek to enable in physical space translate into the virtual? It’ll definitely be good to get feedback from people. In terms of the display that’s happening, I’m curious: what’s the opportunity for people to feed back on the works?

Christopher Griffin: Let’s talk more about the work you’re creating, the environment you’re creating, which, along with the film, will feature your own research drawing from Maud’s letters, coupled with an audio guide that will reflect on your own relationship to Maud and her work. How do you envisage all these elements coming together?

Evan Ifekoya: The thing that things are orbiting around is this website, which I’m calling a virtual shrine, a digital altar to Maud, to her legacy, her life. The starting point, actually, is the egg (fig.5). That is the homepage, the thing that we orient around. The idea is that it is this interactive experience. I’m thinking again through the elements, but also north-south, east-west orientation. So when you interact with the website it’s going to feel very much like you’re in a space. The idea is that there’s one way you can go where the film will be up for a bit and then afterwards there’ll be the documentation of the panel. And then you go in another direction and that’s where the guided audio can begin, which is going to be the series of letters I’ve written where I’m going through my own personal journeying and moments with Maud’s practice or life (fig.6). I realised that this idea of writing a letter to Maud has also been something I’d already done a couple of times. So I’m building on this idea. The way of engaging with the material will be structured through these letters. Then there’ll be another direction you can go in, making visible some of the material that exists on Maud online and pointing to where people can find her work and other archives, physical or digital. It’s also going to be interwoven with the things that I’ve been doing with Midjourney, working with the web designer [Guy Ronen] to turn these things into something that feels immersive. There’ll also be ways to add sound, so the viewer is not just having a passive experience with the material but is actually able to control and adjust and tweak the experience that they have with the material, so that there can be this way of getting closer to it or being an agent in how you interact with it. I’m excited about the fact that it’ll exist virtually, so people can access it anywhere. It felt really important to me that it be a website, something that can exist anywhere.

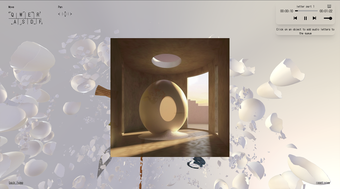

Fig.5

Evan Ifekoya

Ancestor as Muse 2024, screenshot from ‘Letters to Maud’

Digital artwork

https://www.ancestorasmuse.com/

Fig.6

Evan Ifekoya

Ancestor as Muse 2024, screenshot from ‘Letters to Maud’

Digital artwork

https://www.ancestorasmuse.com/

Christopher Griffin: That’s an interesting question, especially in the context of a research residency where, just like all other research practices, you would expect some kind of review or feedback. And the work itself, being dialogical in a way, invites some kind of response.

Evan Ifekoya: Let’s see. It’s definitely a question I have, and I’m also nervous because it is new territory for me to make something in this way. But it does feel really important. I take care. For me there’s a concern, you know. And there’s a desire to do her work justice.

Christopher Griffin: That phrase – ‘to do justice’ – is, for me, fundamental to the ethos and ethics of the research project. What kind of justice can be afforded from researching biases, structural inequalities and suppressed histories? Is it even possible ‘to do justice’ to artworks and histories that have been marginalised or misrepresented within museums by working in partnership with those same museums? How do you measure the changes that need to take place to bring about justice?

Evan Ifekoya: It isn’t something that can be verified immediately. With the ripple effect of the Maud film, that was eight years after the talk I gave in Glasgow. So it’s not something that we can see as linear or that will happen within a specific time frame. These things happen when it’s right. And so it’s about making space for that, for things not needing to happen within these very constrained windows of time.

Christopher Griffin: Research projects and residencies are by definition constrained by time, unfortunately! But on this project, we’ve very much been trying to establish guiding ethical principles that cut through all practices and methods, as well as time constraints. Your work is clearly characterised by a set of principles and convictions that all of us on the project can learn from. I do feel this is where artistic research in particular can be so valuable to a project of this kind. Have you undertaken a research residency like this before, that forms part of a larger collective research project?

Evan Ifekoya: Thank you. It’s helpful for me to hear the work be framed in that way, as being led by this guiding ethos and principles, because it is true. I hadn’t necessarily thought about it in that way.

I’ve definitely done residencies and there’s been research as part of my residency because that is how I work. But I don’t think I’ve been part of a residency that’s framed specifically around this aspect. So I did also come into it with that being a new area of focus for me. It’s been interesting as an artist to come into the space where the other folks are very much looking at this idea of a collection from a very different angle to me. I’m also thinking about the different languages that we use or harness: what terms am I borrowing, but also what terms am I butting up against or not feeling aligned with? I definitely don’t think about my work necessarily in terms of methodologies. But, of course, I have methods and I have ways of working.

Christopher Griffin: The research sector is, of course, another kind of institution, in a way, and bearing in mind what we talked about earlier regarding the sometimes restrictive conditions attached to institutional work, I wonder how you see art functioning within a research project that has specific aims and ambitions? Is there a risk that art and artists can become instrumentalised in relation to project-based research?

Evan Ifekoya: It’s definitely something that I have been thinking about. With this project, it’s more specifically when it comes to the final display, because actually for me the outcome is this work that appears in virtual space. The display is not really a priority or a concern to me, if I’m honest, so I am being very particular about what it means for the work to be part of a display at Tate for that week, because it’s not really what the work is about. For me, there are definitely conditions around participation and what it will look like because I’m not up for the work being instrumentalised and, like I said before, I’m also carrying an artist’s legacy with this work and it’s something that I take very seriously and hold very dearly. So yeah, something I’m very mindful about, you know. Let’s see.

This interview took place online on 9 April 2024. The transcript has been edited for publication by Evan Ifekoya, Christopher Griffin and Andrew Cummings.