According to a much-quoted report from a party celebrating her appointment to Commander of the British Empire in 1938, Ethel Walker (1861–1951) was introduced as ‘England’s leading woman artist’, to which she retorted: ‘There is no such thing as a woman artist. There are only two kinds of artist – bad and good. You can call me a good artist if you like.’1 The account is characteristic of Walker as described in an obituary in the Times of 3 March 1951, that ‘In conversation she was both witty and disconcerting. Her denunciations, delivered in a deep husky voice with her head tilted back and glancing down her nose, were unsparing.’ Yet ‘nothing was more characteristic than her attitude to her own work’, the obituary adds. ‘With a complete absence of self-consciousness and the enthusiasm of a person revealing some obvious truth she would lead one up to a painting or drawing of hers and say, “Now isn’t that lovely?”, her contemplative enjoyment of the thing removing any suggestion of conceit.’2

Despite being one of the most well-known and widely exhibited artists of the first half of the twentieth century, Walker has received comparatively little critical attention, both during her lifetime and posthumously. One significant exception is a publication from the year after her death, written by the art historian and Tate Gallery Director John Rothenstein. In Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith (1952), Rothenstein wrote Walker into history as the most supremely vain artist he was acquainted with. ‘No artist I have ever known has ever felt so assured of the immortality of her work – or the salvation of her soul’, he wrote. ‘That Ethel Walker’s impact upon her generation has been slight (the only influence she has exercised has been upon the gifted spinsters. The “matriarchs” of the New English Art Club) … is due to the completeness of her self-absorption.’ He continued that Walker ‘could have lived happily, so to speak, in a vacuum’.3

Fig.1

Dame Ethel Walker

Two Figures, Study for ‘The Excursion of Nausicaa’ c.1919

Watercolour, graphite and gouache on paper

400 x 229 mm

Tate N03874

Contrary to the prevailing perceptions of women as selfless, passive and maternal, Rothenstein’s depiction of Walker’s ‘self-absorption’ is central to understanding her complex legacy in relation to early twentieth-century gender roles. This article examines how Walker utilised this trait – whether genuine or performed – to gain recognition. An important part of her self-fashioning as an artist was achieved through the creation of what she called her ‘decorations’ – large-scale figurative paintings made using carefully posed models that frequently portray allegorical gatherings of nude or semi-nude women engaged in mysterious rituals, often connected to daily cycles and seasonal changes (see, for instance Two Figures, Study for ‘The Excursion of Nausicaa’ c.1919, fig.1, Tate N03874). Through her correspondence and engagement with London institutions such as the Royal Academy and the Tate Gallery (as Tate Britain was known until 2000), as well as previously overlooked materials in the National Gallery Archive, I explore how Walker’s self-assured persona and her ambition in making these decorations shaped her career, securing her place in the Tate collection between the 1920s and the 1940s. Additionally, Walker’s confidence was likely reinforced by the implicit and explicit advocacy of contemporaries such as the artists Augustus John and Laura Knight and the art historians Frank Rutter and Frederick Brown.

Beyond her self-assured character and influential network, Walker’s engagement with themes such as the female nude bather, utopia, apocalypse, national nostalgia and wartime sentimentality positioned her within significant historical moments and important trends in British art. By analysing the art-historical and display contexts of three major decorations now in the Tate collection – Decoration: The Excursion of Nausicaa 1920 (Tate N03885), The Zone of Hate: Decoration 1914–15 (Tate N05669) and The Zone of Love: Decoration c.1930–2 (Tate N05668) – this article highlights how Walker navigated public institutions and shaped her own legacy, ultimately securing her place within the canon of British art.

A (woman) artist of self-worth

Despite Walker’s assertion that there was ‘no such thing as a woman artist’, her life experiences and professional affiliations suggest otherwise. On the one hand, she was an artist who experienced considerable success. She was the first female member elected to the New English Art Club (NEAC) in 1900, and her works were exhibited widely in London at the Royal Academy, the Royal Society of Arts and the Lefevre Gallery. She exhibited at the Venice Biennale six times, in 1922, 1924, 1928, 1930, 1932 and 1936.4 She was also the second ‘woman artist’ to be appointed a Dame in 1943, following Laura Knight in 1929.5

On the other hand, Walker was acutely aware of the limitations imposed upon her as a woman. She supported the Women’s International Art Club (WIAC), for which she was elected the first and only Honorary President in 1932. In 1928 the art critic Herbert Furst declared that, given ‘women are now professionally as well as politically acknowledged as the equals of men’, the ‘sex segregation’ of clubs like the WIAC were ‘a superfluous anachronism’. Yet he proceeded to contradict himself, writing: ‘The fact is, nevertheless, that the best of the women painters hardly equals the best of the men painters.’6 Evidently, Walker lived at a time when the art world was dominated by male artists, art critics, curators and gallery directors who had a particular view of what art should be. Even though Walker and Knight were elected to the Royal Academy, both were regarded by some as unwelcome outliers. For instance, in his 1914 published memoir the artist George Dunlop Leslie lamented the ‘female invasion’ of the Academy Schools since Laura Herford’s enrolment as the first female student in 1860.7 In terms of art criticism, although Rothenstein had works by Walker in his own collection and had included her among his twenty-two ‘Modern English Painters’ (the fact that she was Scottish introduces another layer of prejudice to his criticism), women only comprised fourteen percent of his survey.8 This also included Gwen John (who was Welsh) and Frances Hodgkins (a New Zealander), both of whom featured alongside Walker in a joint memorial exhibition organised by the Tate Gallery and the Arts Council the same year.9

Amid this competitive context and struggle for recognition, many women of the interwar period, including Walker, positioned themselves as artists through acts of assertion, particularly in terms of language and visibility. This often required assimilating their artistic identity into masculine culture. In a letter sent to the painter Marjorie Watson-Williams (later known as Paule Vézelay) in November 1919, Walker offers advice on how to deal with the ‘“greedy boys” attitude’ that permeated the art world: ‘There is an anti-woman movement’, she warns. ‘So don’t put Marjorie on your labels, just M. Watson-Williams, and they would be sure to take your work for a man’s!’10

While Walker did not take her own advice and sign paintings in this way, she was certainly unafraid of asserting herself within male-dominated institutional arenas. Staying true to her reputation as an artist with a confident and caustic sense of humour, in 1921 she wrote to Charles John Holmes, Director of the National Gallery, asking him to convince the Board of Trustees to purchase some of her work for the national collection. In her first letter, dated 3 February, her plan was for Holmes to first go to her makeshift ‘studio’ – a glorified sitting room in her flat at Cheyne Walk in London’s Chelsea – to see some of her work. After this, she suggested, he could convince the Board to purchase a couple of paintings for the National Gallery of British Art (later known as the Tate Gallery), which at that point – until 1954 – was not independent from the National Gallery.11 Walker writes: ‘I believe you would think well of it. If you would use your influence and help me on this, I should be indeed indebted, for at present I am living from hand to mouth in a most unpleasant manner.’12

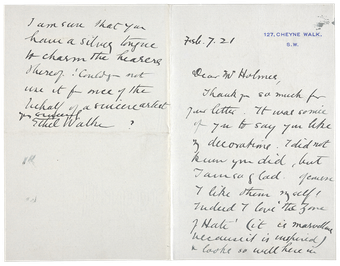

Fig.2

Letter from Ethel Walker to Sir Charles John Holmes, 7 February 1921, pp.1 and 4

National Gallery Archive, NG16/290 © National Gallery, London

Fig.3

Letter from Ethel Walker to Sir Charles John Holmes, 7 February 1921, pp.2 and 3

National Gallery Archive, NG16/290 © National Gallery, London

Living in relative comfort in Chelsea and with a second home in Robin Hood’s Bay, North Yorkshire, it is possible to read Walker’s testimony as tongue-in-cheek hyperbole. On the other hand, it represents the significant challenge faced by many unmarried women pursuing a career as a professional artist at the time. In a typically self-assured fashion, Walker continues: ‘I do think I’m a good artist and am entitled therefore to a little recognition that at least I ought to be in a position to make just a living.’ Although admitting that in recent years she has ‘not sold one sixpence-worth’ nor ‘had a shadow of a commission’, she is quick to state that she has heard positive interest in her work at the current WIAC exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. At the end of her letter, she suggests prices for two large-scale oils shown at the exhibition: £150 for Lilith c.1920 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam) and £250 for Decoration: The Excursion of Nausicaa 1920 (exhibited as Nausicaae).13 In a second letter to Holmes dated 7 February of the same year (figs.2–3), it is evident that Walker received a prompt and positive response from the Director:

Dear Mr Holmes,

Thank you so much for your letter. It was so nice of you to say you like my decorations. I did not know you did, but I am so glad. Of course I like them myself! Indeed I love ‘The Zone of Hate’ (it is marvellous because it is inspired) and looks so well here in studio that I would give anything if you would come see it, and persuade the other members of the Tait [sic] Board to give up time to do so. It is the work that I would far rather be represented to the nation (if I am to be fortunate enough to be bought by it). There are not many works at the Tait [sic] that are as deeply felt or imaginative as this of mine. I would so like to [be] represented now & be shown a little appreciation now since I shall not get any thrills while resting in my tomb!14

In the National Gallery’s inventory of pictures, it is documented that three of Walker’s works were purchased by the Tate Gallery over the next few years. In 1922 the gallery bought Walker’s painting of the same year, Miss Buchanan (Tate N03685), and in 1924 her decoration Nausicaa and the c.1919 Two Figures, Study for ‘The Excursion of Nausicaa’ (see fig.1) for £350 and £14 respectively.15 Her much-cherished The Zone of Hate: Decoration 1914–15, however, would remain in the artist’s studio for some years before it found its way to Tate. The price of £350 for Nausicaa was £100 higher than originally suggested by the artist in her letter. Despite her apparent confidence in her work, Walker’s pricing in this instance suggests she undervalued herself in the art market, possibly reflecting and reinforcing the broader tendency towards the economic and symbolic devaluation of women’s work in comparison to that of their male counterparts.16

Indeed, despite increasing opportunities to exhibit at the NEAC, the London Group and the WIAC, women artists like Walker faced significant disparities in critical and financial recognition compared to male artists. For while Walker may have been struggling financially in 1921, this was evidently the case in 1949, too, when the artist Evelyn Alice Clutton-Brock asked the Chairman of the WIAC General Meeting ‘if any financial assistance could be given to Dame Ethel Walker the President of the Club who had been in bad health recently’.17 The same year, the Royal Academy granted Walker £100 from its benefactors’ fund.18 On hearing of this endowment, Sir Alfred Munnings, President of the Academy, cruelly declared: ‘Ha ha ha I thought she was a rich old woman – that just shows she isn’t any good.’19 Munnings’s comment reflects his ongoing sparring relationship with Walker, particularly regarding the visibility and display of their respective work at the Academy.20

Unafraid to participate in jocular taunts and self-praise, Walker asserted a performatively ‘masculine’ artistic persona. As the art historian Justine Kenyon argues, Walker may have been aligning herself with the personalities of the many male artists she admired. Augustus John’s ‘leonine personality’ was well known, as was Wilson Steer’s lifelong devotion to his ‘absorbing passion for painting’, and Walter Sickert, who taught Walker at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, was known for his arrogant self-belief. When Steer died in 1942, Walker is reported to have exclaimed, ‘Now he and Sickert are gone I’m the only artist left!’21

Walker’s alignment with these artists reflected not only her self-belief, but also the evolving role of the ‘woman artist’ in early twentieth-century Britain. To her female friends, her so-called ‘vanity’ was a justifiably assertive character trait within the context of a competitive art world. Grace English, the artist and long-time friend of Walker who left Tate an archive of Walker’s correspondence and notes, described her as ‘devoted to her art’, asserting there was ‘no conceit in it’.22 Similarly, Walker’s niece, Rachel Fourmaintraux-Winslow, wrote to Rothenstein that ‘Ethel has no vanity – she knows her worth and the worth of her paintings’.23 Beginning her career relatively late – she first exhibited at the Royal Academy at the age of thirty-seven and was writing to Holmes as she neared sixty – Walker’s maturity and life experience shaped her self-assurance, allowing her to navigate the art world with confidence and autonomy.

Painting women

Fig.4

Dame Ethel Walker

Dame Ethel Walker c.1925

Oil paint on canvas

613 x 808 mm

National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 5301

Walker’s confidence as an artist is powerfully conveyed in her self-portraits, particularly in a 1925 example at the National Portrait Gallery, London (fig.4). Dressed in a suit – a garment she wore frequently – Walker adopts a direct gaze, her arm angled with subtle assertiveness. Although no easel or paintbrush is visible, her pose evokes the act of artistic creation: her steady gaze mirrors that of an artist studying their reflection, while the slight tilt of her head suggests her attention is divided between the viewer and the imagined canvas. Seated upright, her posture echoes the straight-backed chair behind her, reinforcing a sense of composure and professionalism. Most strikingly, her suit reflects contemporary associations between masculinity, authority and expertise, emphasising her own assertion of her professional identity as an artist. By contrast, a later self-portrait, created around 1930 and presented to the Tate Gallery in 1951, depicts her brush in hand with a canvas just visible to the right of the painting (fig.5, Tate N06006). Wearing a low-cut dress and gold chain, she meets our gaze with a raised eyebrow and wry smile. As Kenyon notes, despite being in her mid-sixties at this point, Walker painted herself ‘with all the bloom and freshness of a young woman’.24

Fig.5

Dame Ethel Walker

Self-Portrait exhibited 1930

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 765 mm

Tate N06006

With her cheeks flushed red and her pose in recline rather than in upright action, the Tate self-portrait merges the identity of the artist with that of the female model. In Modern English Painters, Rothenstein confidently stated that ‘portraits of girls’ were one of Walker’s ‘favourite subjects’, while her obituary claimed that she ‘painted several good portraits of men but it is with young women that she excelled’.25 In 1952 the art critic Thomas Wade Earp echoed this sentiment, observing that her male portraits were less successful, stating ‘She painted women, indeed, as though they were flowers’.26

Earp’s observation resonates strongly with Walker’s 1937 portrait of the artist Vanessa Bell (fig.6, Tate N05038), presented to the Tate Gallery by the Contemporary Art Society in 1939. Rendered with Walker’s impressionistic touch, Bell’s features appear far softer and more delicate than in Duncan Grant’s often austere depictions or Bell’s own radically bold and unkempt self-portraits.27 Posed with arms crossed and leaning slightly forward, Bell gazes contemplatively to the side. One of Walker’s favourite poses, often used in her portraits of women, it also evokes familiar photographic portraits of Bell, suggesting that Walker captured not only the sitter’s posture but also her personality – albeit in a ‘pretty’ refinement.28 Unlike the assertive gaze of Walker’s self-portraits, her portraits of other people – whether male or female – are more passive. But it is the prettification of her female subjects – achieved through petite, genial facial features and unassertive poses, as seen in Bell’s portrait and countless others, such as Miss Buchanan c.1922 (fig.7) – that contrasts sharply with the masculine confidence Walker projected in her depictions of herself. These works align with more traditional notions of femininity and delicacy, highlighting the tension between Walker’s portrayal of herself as a professional artist and her rendering of women within conventional ideals of beauty.

Fig.6

Dame Ethel Walker

Vanessa 1937

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 508 mm

Tate N05038

Fig.7

Dame Ethel Walker

Miss Buchanan c.1922

Oil paint on canvas

765 x 637 mm

Tate N03685

Although there have been no explicit comments recorded regarding Walker’s sexuality, either by herself or by those who knew her, the tender focus of Walker’s portraits of women, alongside implicit references in biographical fragments from those who knew her, have fuelled queer interpretations of her work. Grace English, in her unpublished monograph on Walker in the Tate Archive, reflects on the artist’s intimate relationship with the artist Clara Christian. The two met at Putney School of Art, later sharing a cottage in Pulborough, West Sussex, until their bond was disrupted in 1900 by the Irish writer George Moore, whom English claimed ‘took Claire [sic] Christian from [Walker]’.29 It has also been speculated that Walker and Christian inspired the characters of Stella and Florence in Moore’s memoir Hail and Farewell (1911–14), which describes how the women ‘often spent nights together in the Sussex woods’.30 This experience of losing her companion may have influenced Walker’s comments on the ‘perfidy of men’ and her advice to young women to avoid marriage. These were given at a 1933 tea party with Alice Mary (née Knewstub), Lady Rothenstein and her daughter Elizabeth, at which Walker recounted her experience of her relationship with Moore. In response, Lady Rothenstein broke ‘into mocking laughter’ and asked how ‘the world would go on if all the young girls refused to marry’.31

It is within this context that Walker’s loose involvement with the artists, writers and intellectuals of the Bloomsbury Group may be read for its queer connotations. A generation younger than Walker and therefore less entrenched in Victorian morals and ideals, its members are known for embracing same-sex relationships and questioning social conventions. This connection is exemplified by the attendance of Grant, Bell and Bell’s sister, the writer Virginia Woolf, at a party held in Walker’s honour at the Belgrave Hotel, London, in March 1935. Hosted by William Rothenstein, the artist and husband of Lady Rothenstein, the event also included Holmes, Steer and the artist Henry Tonks, and was presided over by Frederick Brown, one of Walker’s most ardent supporters. Woolf recorded the event in her diary: ‘It was great fun’ and ‘I enjoyed myself enormously’, although there were ‘Not many artists, all flashy people who don’t belong anywhere’.32 If accurate, this observation suggests that Walker’s following, while substantial enough to warrant a special dinner, may have been composed of socialites or cultural enthusiasts as much as fellow practitioners within the artistic community.

Fig.8

Dame Ethel Walker

Lilith exhibited 1916

Watercolour and graphite on paper

508 x 324 mm

Tate T00131

Woolf had probably met Walker only two years prior to this event. On 1 April 1933 Woolf wrote to her lover Vita Sackville-West, ‘I am going to be painted, stark naked, by a woman called Ethel Walker who says I am the image of Lilith’. The fact that this painting has yet to be identified – if indeed the sitting did take place – is a significant loss for those engaged in exploring sapphic narratives within British art. We do at least know that Woolf visited Walker’s studio, as evidenced in her letter: ‘she … lives, eats, sleeps, drinks … in one room overlooking the river. Swans float practically in at the window.’33 The story also adds a queer dimension to Walker’s repeated fascination with Lilith, the demonic female figure of Jewish folklore who was the predecessor to Eve. As we see in her preparatory watercolour sketch for Lilith, exhibited at the NEAC in the summer of 1916, Walker depicts Lilith as a woman in autoerotic reverie, while Adam relegated to a barely visible figure slumped against a tree in the background (fig.8, Tate T00131). The diminishment of Adam’s presence in Lilith’s self-absorption (a characteristic that, as we have seen, was attributed to Walker by her contemporaries) creates a queer-coded image of female sexual pleasure enjoyed without a man.

Utopian visions

Walker’s depictions of Lilith reflect her broader fascination with the female nude, a recurring theme in many of her ‘decorations’. In these large-scale works, female bodies are often gathered in an intimate assembly, and whether praying, gesturing, bathing or reclining, all carry sapphic connotations. One of Walker’s earliest decorations, the The Excursion of Nausicaa of 1920 (fig.9), was inspired by Homer’s ancient Greek epic poem The Odyssey and exemplifies this approach. When presented to the NEAC select committee, this canvas, measuring almost 2 by 3.5 metres, was met with ‘spontaneous and enthusiastic applause’.34 As her letters to Holmes indicate, Walker’s self-advocacy led to the painting being purchased by the Tate Gallery in 1924. Writing at the time to James Bolivar Manson, Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery, Walker described the painting as depicting the moment when the Phaeacian princess Nausicaa and her attendants, granted a wagon and mules by her parents, go to a river near the sea to wash clothes and prepare for a picnic. Among the array of figures, a ‘goat girl’ listens to ‘strange voices that are sounding in her usually silent little wood’; while to ‘show it is the sea, a girl, nude, has stepped up on the bank after bathing’.35

Fig.9

Dame Ethel Walker

Decoration: The Excursion of Nausicaa 1920

Oil paint on canvas

1835 x 3670 mm

Tate N03885

The painting reimagines a passage from Book VI of the Odyssey where Nausicaa, prompted by the goddess Athena, encounters the shipwrecked Odysseus while at the river with her maids. Yet Walker’s depiction diverges in focus, emphasising the tranquil, all-female intimacy of the moment which reflects her broader artistic interests. Her interpretation captures the essence of Homer’s imagery: ‘When they had all purified, and no spot / Could now be seen, or blemish more, they spread / … and smoothing o’er with oil / Their limbs, all seated on the river’s bank’.36 The scene of the well-travelled, much-tried male figure of Odysseus revealing himself to a virginal young woman engaged in laundering also inspired the ‘Nausicaa’ episode of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses (1922), written around the same time Walker created her decoration. Joyce uses the story to explore erotic tensions through symbolic oppositions: the man is dirty; the woman cleans and preserves.37 In contrast, Walker’s portrayal eschews this voyeuristic lens, omitting Odysseus entirely and reframing the mythological scene as one of harmonious female companionship, a focus reflected in her detailed description to Manson.

Fig.10

Edward John Poynter

Nausicaa and Her Maidens Playing at Ball 1873

Oil paint on canvas

280 x 780 mm

Private collection

While earlier depictions of this story often centred on Odysseus – portraying Nausicaa and her maidens in servile roles supplying the shipwrecked hero with food, clothing and wine – Walker’s choice to focus on Nausicaa bathing with her companions was not entirely unprecedented. Edward John Poynter’s Nausicaa and Her Maidens Playing at Ball 1873 (fig.10) caused a sensation when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy, with crowds drawn by the celebrated beauties who modelled for the painting, including the actress Lillie Langtry as Nausicaa.38 Other depictions of Nausicaa and her maids were submitted to the Academy over the following decades, and in 1915 Lucien Simon painted Nausicaa (Petit Palais – Musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville de Paris), which later occupied ‘a wall to itself’ at the Twentieth Annual International Exhibition of Paintings at the Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, in 1921.39 Yet Walker’s painting is markedly different from these examples. In 1931 the art historian Mary Chamot, who became the Tate Gallery’s first female curator in 1949, described its ‘rhythmic emphasis on contours’, the ‘sensuous delight in youthful nudes amid luxuriant vegetation’ and the ‘almost ritual effects produced by the reiteration of certain movements’.40 Walker’s impressionistic touch blends the translucent, overlapping bodies of her maidens into the surrounding undergrowth, creating an ethereality that challenges traditional modes of viewing and objectification.

European ‘masters’

Fig.11

Paul Cezanne

Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses) c.1894–1905

Oil paint on canvas

1272 x 1961 mm

National Gallery, London, NG6359

Walker’s Nausicaa shares a clear affinity with Paul Cezanne’s blue-hued scenes of female bathers in woodland glades (fig.11), which draw on the classical tradition of nymphs and goddesses in idealised pastoral settings, particularly those of the Venetian Renaissance. Walker may have encountered Cezanne’s work in Roger Fry’s post-impressionist exhibitions at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1910 and 1912. Cezanne was prominently featured in these displays, which contributed to his later reputation as the ‘father of modern art’.41 His bathing scenes, along with those by fellow French artists Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Paul Gauguin, reinterpreted classical themes to demonstrate a new visual approach and an alternative conception of ‘natural’ and physical beauty. By the 1920s the bathing scene became a recurring motif in modern art, and Walker’s selection of this theme in Nausicaa positioned her within both a contemporary artistic dialogue and the broader history of depictions of the female nude bather in old-master painting. As Frederick Brown observed in a letter to the artist George Clausen in 1940, the year Walker was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy, her work asserted a connection to this enduring tradition:

I was glad to hear of Miss Walker’s election long overdue. She is in spite of some deficiencies an outstanding artist and the most imaginative painter this country has produced in a long time and I predict that some day, her ‘Nausicaa’ will be seen in the NG [National Gallery] among the old masters, along with a few others of our best painters Steer, John, yourself and some others who are better than some of the Victorian artists shown there. Why is Cézanne [sic] shown there even temporarily? He is much overrated.42

Fig.12

Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes

Summer before 1873

Oil paint on canvas

432 x 622 mm

National Gallery, London, NG3422

Brown had long been an advocate for and collector of Walker’s work, writing forewords for her 1927 show at the Redfern Gallery and her 1931 exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery. In both texts, he highlighted Nausicaa in particular, describing it in the latter as ‘certainly one of the most, if not the most, charming of the modern pictures, English or foreign, in [Tate’s] collection’.43 Given that Walker herself advocated for the work’s acquisition to the national collection, the scale and subject matter of Nausicaa were evidently intended to elevate it to the classification of European ‘masterpiece’, a categorical prerequisite required for collection and exhibition at the National Gallery.44 Indeed, Frank Rutter made distinct reference to Nausicaa in his Modern Masterpieces (1935), describing Walker as ‘a most original artist and an exquisite colourist’. Rutter places her within a tradition that was, following Fry’s exhibitions, recognisable to Britain’s growing national collection of French post-impressionist works. He notes how in her ‘decorations’ Walker ‘deliberately becomes post-impressionist in style, that is to say, she employs simplification and lays stress on line, thus following in her own individual way the principles of mural decoration laid down by [Pierre-Cécile] Puvis de Chavannes and popularised later by Gauguin.’45

Fig.13

Paul Gauguin

Faa Iheihe 1898

Oil paint on canvas

54 x 169.5 cm

Tate N03470

If we take Rutter’s comparison seriously, then we can suggest that Walker’s letters to Holmes were likely to have been informed by the collecting practices of the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery. In 1917 and 1919, not long before Walker finished Nausicaa, four works by Puvis de Chavannes had entered the National Gallery’s collection, although most of these were preparatory sketches, such as Summer, made sometime before 1873 (fig.12).46 Gauguin’s Faa Iheihe 1898 was also presented by Lord Duveen in 1919 (fig.13, Tate N03470). While much larger in scale, Nausicaa bears a resemblance to Gauguin’s frieze-like painting in both subject matter and composition. ‘Faa Iheihe’ is an inaccurate transcription of the Tahitian word ‘fa’ai’ei’e’, meaning to beautify or adorn oneself. It refers to a cultural practice in Tahiti where people prepare themselves with care by dressing, combing their hair or using perfumes, especially before social gatherings or romantic encounters.47

Fig.14

Peter Paul Rubens

The Judgement of Paris probably 1632–5

Oil paint on oak

1448 x 1937 mm

National Gallery, London, NG194

It is tempting to see Nausicaa as working in a similar mode of exoticisation to Faa Iheihe, complete with nude women among animals within a natural setting. But there are more established art-historical references at play here. Letters in the National Gallery archive reveal Walker’s admiration for the old masters.48 She registered as a copyist at the Gallery in January 1938, although this was almost certainly a renewal of her registration, given that she was already seventy-six years old.49 She produced numerous undated copies of works in the museum’s collection, including those by Thomas Gainsborough, François Boucher and Peter Paul Rubens. Among them was Rubens’s The Judgement of Paris c.1632–5, which, like Nausicaa, features nude women in a pastoral setting (figs.14–15). In Rubens’s scene, Paris, the Prince of Troy, is tasked with judging the beauty of the goddesses Athena, Hera and Aphrodite, who reveal themselves at his request. Walker revisited this classical theme in a 1930 watercolour, but, as in Lilith and Nausicaa, she marginalises the male figure, this time removing him entirely (fig.16). Instead, the three nude women, flanked by two seated women to the left, gaze toward an unseen presence to the right. Like Walker’s other figurative works, she presents an all-female grouping situated in an Arcadian paradise of trees, exotic birds and goats. By omitting Paris, Walker departs from traditional representations of the subject, particularly of the kind she was copying at the National Gallery. Yet the women are still presented for judgement – this time, by the viewer.

Fig.15

Dame Ethel Walker

The Judgement of Paris

Pencil and watercolour

229 x 260 mm

Private Collection

Nausicaa therefore shares thematic and stylistic affinities with various artists held within the national collection or having been exhibited prominently by the time it was painted: Cezanne’s dreamy-blue bathing scenes, Puvis de Chavannes’s flat, simplified forms, Gauguin’s exoticised pastoral scenes and old masters such as Rubens’s classical references to feminine beauty. Yet Nausicaa maintains its own distinct identity within the early twentieth-century post-impressionist movement. The direct implication of ‘natural beauty’ and cleanliness in depictions of women bathing (as described sensuously in the Odyssey) would have been appealing to Walker. Like the mythical Paris, Walker had her own judgement to make about female beauty, sought out in the models she chose. In the Tate Archive there are numerous references to her loathing women in make-up, preferring a more ‘natural’ look, as illustrated in one letter to Grace English from May 1935:

Fig.16

Ethel Walker

Paris and the Goddesses 1930

Pencil and watercolour

479 x 384 mm

Private Collection

I have a nice model for you. No makeup [sic], such lovely natural curly golden hair like a Botticelli angel, with features and expression, a nice long neck … I shall also have a very nice model to give you, a German, with marvellous smooth silken yellow gold hair, no fringe … also not made up.50

Walker’s opinions impacted her legacy, with her obituary in the Evening News dubbing her ‘The Artist Who Hated Powder and Paint’: ‘To describe anything hideous she used to say: “As ugly as a 1938 woman.” She would not allow any model wearing lipstick to enter her house. They wiped off their rouge outside.’51 While this account seems dubious (many of her female sitters, such as Miss Buchanan, appear to be wearing makeup, although these could be exceptions or artistic embellishments), it underscores her unrealistic vision of femininity: women should be assertive and plain enough to be taken seriously, yet still beautiful, resembling the idealised figures depicted by the old masters. Walker’s puritanical idealism in this regard smacks of modernist fears over mass production and over-consumption, of the expanding beauty industry and the made-up faces of Hollywood’s silver screen. Yet her all-female compositions still offer a breakaway from those produced by men. To enter the world of Walker’s paintings is to be confronted with a paradox: they are representations that, while part of a male art-historical lineage, show a sapphic, utopian world without men in which women are made in Walker’s own idealised image.52

The decorations: Modernity and tradition

Although Walker called her large paintings ‘decorations’, the term is misleading to art historians today, suggesting they were intended as decorative pieces or murals. As the art critic and scholar Katy Deepwell argues, Walker’s decorations were not commissioned, nor was a specific site designated for their display. Creating a link to Fry’s definition of a ‘decoration’ as carrying a depth of meaning, representing the embodiment of form and unity and reflecting the functioning of the ‘spirit’, Deepwell points out that Walker began producing and exhibiting these allegorical works around 1912. As we have seen, this was a pivotal year in the London art scene marked by Fry’s Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition.53

Fig.17

Augustus John

Lyric Fantasy c.1913–14

Oil paint and graphite on canvas

2380 x 4720 mm

Tate T01540

Superseding history painting in the early twentieth century, ‘decorative painting’ was a broad term that could be interchangeable with mural painting in its traditional meaning of a work designed or intended for a particular architectural space. In 1905 the artist Walter Crane had noted how portable pictures could function as movable panels of decoration to achieve the same effect as mural painting. He described this as a ‘mural feeling’ – a quality he associated with the work of art’s wider relationship with its environment, similar to Fry’s idea of uniformity.54 This is evident in what Kenyon argues as the idyllic, ‘primitive and lyrical’ vision of Augustus John’s Lyric Fantasy c.1913–14 (fig.17, Tate T01540), one of three decorative schemes commissioned by Hugh Lane in 1909 for Lindsay House, 100 Cheyne Walk, near Walker’s home at 127 Cheyne Walk.55 John was incredibly inspirational for Walker, and by comparing them through the concept of the ‘primitive’, Kenyon draws attention to how we might see Walker’s large-scale ‘decorations’ engaging with an aesthetic idealisation that was popular among modern European artists of the time. The idea of the ‘primitive’ was rooted in the belief that early human history and non-European cultures embodied a simpler, less civilised way of life and thus a utopian existence. Such depictions often led to the stereotyping of cultures and peoples that were not the artist’s own. In presenting an idealised world, Walker’s works reflect her negotiation of contemporary themes and hierarchies in painting, aiming to both secure a position within the canon of art history and to attract lucrative commissions. Although such works were difficult to sell, their intended audience was clear: the private estates of wealthy patrons or, ultimately, the public museum.

In addition to her ties with Augustus John and the post-impressionist movement, Walker’s work was influenced by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which first appeared in London in 1911. Preceding John’s Lyric Fantasy, her painting Decoration for an Ivory Room: Invocation to the Dance c.1913 (fig.18) exhibits the dynamic sense of movement and theatricality of the Ballets Russes. Ballet was an art form that Walker admired and she invited the dancer Natalia Russell to model for several figures in Nausicaa and The Zone of Love.56 Unlike these later works, however, Decoration for an Ivory Room features both men and women, situated in a setting that is situated in an identifiable setting – it is likely inspired by Robin Hood’s Bay, a recurring backdrop in Walker’s group compositions.57

Fig.18

Dame Ethel Walker

Decoration for an Ivory Room: Invocation to the Dance c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

1070 x 1680 mm

Rotherham Heritage Services, ROTMG: OP.1996.2

Walker’s inclusion of Black figures in Decoration for an Ivory Room offers a complex duality. On one hand, it expresses an optimistic vision of interracial coexistence within her conception of utopia, where all figures appear on equal footing. On the other, it is rooted in imperialist notions of superiority, as reflected in the artistic movement of primitivism. Like Gauguin’s romanticised depictions of the South Seas, Walker’s work reflects a Eurocentric gaze that exoticises diversity while upholding colonial hierarchies. For instance, the figure with his hand raised, positioned at the front of the painting to the left of the seated girl with both hands lifted, is thought to represent the ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky in his role as the Golden Slave in the 1910 ballet Schéhérazade.58 The presence of Nijinsky as the Golden Slave, a character he performed in blackface and who in one scene is involved in an interracial orgy, underscores the painting’s entanglement with contemporary exoticising and orientalist narratives of Asia and North Africa.59 Such depictions presented these cultures as inferior or underdeveloped in comparison to the perceived superiority of white European culture. Known for its fusion of dance, music and stage design, the Ballets Russes undoubtedly left an impression on Walker, who integrated similar elements of theatrical fluidity and ornamentation into the large allegorical compositions in her later work. This artistic exchange, however, underscores the racial and imperialist overtones of both the Ballets Russes’s and Walker’s idea of utopia. It also reveals the wider cultural influences on Walker and her engagement with avant-garde developments beyond Fry’s exhibitions and indeed the realm of painting.

Walker’s decorations exemplify the tension between the modern and the traditional. Although Frederick Brown’s prediction that Nausicaa would one day be displayed alongside the ‘old masters’ at the National Gallery remains unrealised, both his assertion and Rutter’s comparison of Walker’s work with that of artists such as Puvis de Chavannes position her within an established art-historical canon. It is hardly surprising, then, that in 1920 Walker not only painted her scene of female bathers but also petitioned the Director of the National Gallery for its acquisition. Her pride in being included and shown in a prestigious national collection is maintained several years later in a letter to Grace English from April 1938, in which she explains that ‘Nausicaa is hung splendilous [sic]’ at the Tate Gallery, and urges English to go and see it ‘for the first time’. English separately observes that this afforded Walker ‘the greatest pleasure of all’.60 It is perhaps her pride in institutional acceptance that led Walker, as the recently appointed President of the WIAC, to address guests at a Club Dinner in 1934 saying that ‘while she very much liked’ the club’s recent exhibition, ‘she wished that members next year would endeavour to send more subject pictures to relieve the landscapes, portraits and flowers’.61 As she had intended with her own decorations, she wanted women to compete with men in the art world.

Recognition was evidently important to Walker. ‘The Royal Academy was not really Ethel Walker’s spiritual home’, Grace English writes, ‘and her work was muted in this big assembly.’62 Meanwhile, Walker’s obituary in the Evening News states that ‘her quarrel with the Royal Academy probably accounted for the fact that although her pictures were regularly hung at Burlington House for many years and several were bought for the Tate Gallery, she was not elected an R.A. until 1940’.63 In fact, Walker was never given full Academician status. The Academy’s nomination book for Associateship (ARA), a status created to generate a pool of artists from which to elect full Academicians, shows that Walker was first nominated ARA as early as 1931.64 Included among the twelve supporting signatures is Laura Knight, who had herself been elected ARA in 1927 and would later receive full RA in 1936 and Senior RA in 1953. As the first female RA, as well as President of the Society of Women Artists between 1932 and 1967 (of which Walker was also a leading member), Knight endorsed Walker’s election, supported by her attendance during the General Assembly meetings for elections that eventually led to Walker receiving enough votes for ARA in 1940. Knight’s endorsement is perhaps accounted for by her vocal admiration for Annie Swynnerton, who in 1922 became the first woman to be elected ARA. In her autobiography published in 1936, the year of her RA election, Knight paid a now-often-quoted tribute to Swynnerton, who had died three years prior:

We women who have the good fortune to be born later than Mrs Swynnerton profit by her accomplishments. Any woman reaching the heights in the fine arts had been almost unknown until Mrs Swynnerton came and broke down the barriers of prejudice.65

Knight’s support of Walker was likely part of a broader movement during this period, one that sought to emulate Swynnerton’s efforts in securing a place for women within the art establishment. But like Swynnerton, who was seventy-eight at the time of her election, Walker was elected ARA towards the end of her career when she was seventy-nine years old. This meant that due to the Senior Order introduced in 1918, by which all Academicians and Associates on reaching the age of seventy-five became senior members to create a vacancy in the other categories of membership, unlike Knight she did not qualify to advance to the next stage of the Academy.66

Although there was evidence of progress, in the context of what many saw as an ongoing undervaluation of Walker and of women more broadly in this period, Augustus John, a staunch supporter and friend of Walker, who had himself been elected RA in 1928, drafted a letter to the Editor of the Times in October 1942:

Sir, it is remarkable and I think deplorable that the present exhibition of Miss Ethel Walker’s painting at the Lefevre Gallery, King St, St James’s should have been almost ignored both by the Press and the public. A few days only are left in which to view the exquisite work of one of the finest living painters certainly the greatest woman artist this country can now boast of.67

Despite John’s positive sentiment, by relegating Walker to the then-customary label of ‘woman artist’, we see an example of the very issue she complained about to English during her 1939 exhibition at Lefevre, when she referred to ‘the limited survey of all the obtuse press opinions … Because I am a woman I have to be patronised it seems with a sea of futilities and adjectives.’68 John’s well-meaning support of Walker was nevertheless significant at this juncture in her career and in the context of wider world events. His declaration that she was the best ‘this country can now boast of’ was common rhetoric in supportive statements recorded about Walker since the late 1930s. This was a time of global uncertainty and anxiety in response to the Second World War in which emphasis was often placed on national identity and the artists who were worthy of constituting it.69

Two paintings for the nation

Between the late 1930s and early 1940s two of Walker’s decorations were displayed in a way that powerfully conveyed the emotional resonances of war and nationhood. These were her ‘zone’ pieces, The Zone of Hate: Decoration 1914–15 (fig.19) and The Zone of Love: Decoration c.1930–2 (fig.20). Both almost 2.5 metres square, these large allegorical decorations offer contrasting dystopian and utopian visions. The Zone of Hate presents a dark, chaotic scene, embodying the devastation of war through several allegorical figures, whereas The Zone of Love offers a serene, luminous vision of spiritual harmony and heavenly renewal. In December 1940, coinciding with her election as ARA and one year into the Second World War, Walker expressed frustration over the lack of recognition for these works. Writing to a Mr Haward about Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery, she lamented: ‘I could not put it into his head to start trying to get them bought for the NATION?! I know they are my masterpieces, far the best things I have achieved in my life.’70 This plea can be seen as a response to Clark’s male-dominated wartime exhibitions earlier that year, including British Painting Since Whistler, in which John’s Lyric Fantasy was displayed, with the Burlington Magazine describing the painting as evidence of ‘John’s genius as a mural painter’.71 Walker’s pointed remarks to Haward highlight both the gender bias she experienced and her unwavering belief in the importance of her own contributions to British art and its national narrative – a conviction anchored in the monumental ambition of her ‘zone’ works.

Fig.19

Dame Ethel Walker

The Zone of Hate: Decoration 1914–15

Oil paint on canvas

2476 x 2464 mm

Tate N05669

Fig.20

Dame Ethel Walker

The Zone of Love: Decoration c.1930–2

Oil paint on canvas

2440 x 2440 mm

Tate N05668

The Zone of Hate had been previously exhibited at the NEAC in the summer of 1917 and was described in the catalogue as ‘5 Forces, Hate, Life, Death, Destiny, the World Sorrow. The 2 figures on the left and right completing arabesque symbolize (1) The Mother of the Race, (2) The Earth covering the dead’.72 Walker had wanted to create a companion piece to this work for some time, and more than a decade later she painted The Zone of Love.73 Following the latter’s first display at the Royal Academy in 1932, the two decorations became an instant pairing, travelling together for exhibitions. Indicative of their ‘mural feeling’, they were exhibited in Mural Decorative Paintings at the Whitechapel Art Gallery between May and June 1935, and at Wildenstein, London, between November and December 1936. The second of these shows offered Walker ‘the greatest pleasure’, Grace English records, showcasing the full breadth of her work. It included four examples of her decorative works, alongside portraits, marine and landscape scenes, and flower paintings. ‘The decorations were beautifully hung’, English states, ‘one at each end of the Gallery and one on either side’.74 A press handout in connection with this exhibition drew particular attention to her two ‘zone’ decorations:

Miss Walker started the first [The Zone of Hate] within a week of the outbreak of war in 1914. At a time when most people thought the war would be a matter of a few weeks, she was inspired by a foreboding that it would last for years. All the figures in the painting are entirely allegorical, but the war mentality was so strong at the time that people complained because she had not included the figure of the [German Emperor] Kaiser [Wilhelm II] … She is the only English woman painter of note to work on such a large scale. In spite of their size, she has no big studio, but works in the small sitting room of her flat, looking out over the river, in Chelsea. Both the Zone of Hate and Zone of Love were painted there, and to get them to the exhibition the canvasses had to be taken out of their frames and rolled up.75

The significance of The Zone of Hate lies both in Walker’s status as ‘the only English woman painter of note to work on such a large scale’ and in her pioneering engagement, as early as 1914, with war as subject matter. At a time when depictions of war were primarily associated with male artists such as Paul Nash, John Nash, Stanley Spencer, C.R.W. Nevinson, Eric Kennington and David Bomberg, Walker’s focus on the subject is notable for its rarity among women artists of the period. This rarity was largely due to disparity in official commissioning, and those women who did address war in their art – such as Anna Airy – often painted documentary-style depictions or focused on women’s work. It is no wonder that Walker described The Zone of Hate to Holmes as ‘marvellous because it is inspired’. It was an attempt to engage with war on the scale and with the tone and allegorical approach to narrative seen in history painting. This departure from the conventional scale and subject matter tackled by female artists underscores Walker’s ambition, challenging both gender expectations and artistic norms.

Fig.21

Ethel Walker in her studio, 1941

Tate Archive, TGA 716/84

The press release for the Mural Decorative Paintings exhibition is significant in highlighting the physical constraints under which she was working in her Chelsea flat. Whereas married women were often confined to the domestic sphere due to the expectations of marriage and motherhood, Walker’s lack of a dedicated studio space may have been a result of her financial struggles living as a single woman, as implied in her letters to Holmes. With the exception of the occasions when it was being exhibited, The Zone of Hate remained in Walker’s studio for many years, ‘Dominating the room’, as English tells us, ‘and the background to so many of her figure and head paintings’.76 It also appears as a backdrop in a photograph of the artist in her studio from 1941 that later appeared in a Vogue article in 1952 (fig.21).77 With reference to this photograph, Deepwell compares The Zone of Hate’s position in Walker’s home studio to that of Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), which also remained in the artist’s studio for years and was much photographed alongside him there.78 In a similar vein of artist mythmaking, the photograph of Walker shows her dressed in masculine attire and wearing a prominent ring on her wedding finger, which, whether intentional or not, playfully symbolises her being wedded to her art – or at least to the painting that sits behind her.

Walker made many preliminary sketches and watercolour paintings for her ‘zone’ decorations, using models in her studio and at evening classes at Chelsea Polytechnic. The relative optimism of the interwar period shapes the tone of her second painting of the pair, evidently created to revitalise the first. Regarding The Zone of Love, English wrote:

In contrast to ‘The Zone of Hate’, where the forces of evil are shown destroying the suffering, sinking figure of mankind, ‘The Zone of Love’ is conceived in a lighter key and has a peaceful serene atmosphere. Here also the soul is represented as a young girl just awakening into the celestial sphere. Her guardian angel attends her, and another angel is holding out her heavenly raiment. The landscape is adorned with birds and flowers, and a host of angels is seen in the background … These allegorical paintings were inspired by Ethel Walker’s enthusiastic interest in the religious doctrines of Swedenborg and of the East.79

Walker’s ‘zone’ paintings combine Christian iconography of the old masters with her interest in Taoism – a Chinese philosophy focused on living in harmony with the natural flow of the universe. The Zone of Hate shows a combination of other cultures and religions, including Buddhism, Hinduism and Christianity: behind the figure with the halo is a cross-legged person meditating, while the horned, devil-like male figure has a third eye. This latter figure bears an aggressive expression and stance, as if poised to strike. In this way The Zone of Hate, unlike The Zone of Love and Nausicaa, connects Walker’s dystopic vision to the destructive, over-consumptive greed of men. As the Evening News reported, she was a ‘vegetarian’ who ‘maintained that the world’s troubles were due chiefly to men eating meat’.80 It is tempting to read this quotation, which connects dietary ethics and moral decline, as a critique of human greed and consumption that carries over into Walker’s work. The Zone of Hate channels her dystopian perspective on spiritual decay into a pointed critique of male-driven gluttony, aggression and wastefulness as underlying forces of war. As outlined in her 1919 letter to Vézelay, this view is reinforced by Walker’s disapproval of the art world’s ‘“greedy boys” attitude’.81

In tone, mood and as a depiction of an intimate female realm, The Zone of Love, by contrast, offers a utopian world that has much in common with Nausicaa. This comparison was noted by Rothenstein in Modern English Painters, singling out these two works as his favourite of Walker’s decorations that show a classical ‘Golden Age’, described as ‘an imagined world of beauty: a rainbow-hued springtime world peopled by slender young girls, naked, dreamy and innocent’.82 Walker’s choice of the word ‘zone’ is important, having Latin roots in zona, meaning the celestial zone of a geographical belt, itself developed from the Greek zōnē, a belt or the girdle worn by women at the hips. Whether or not Walker was aware of this, her ‘zone’ decorations have an etymological connection that deepens the reading of her paintings, where women occupy central roles in these allegorical narratives. A zone, much like the girdle – including the Holy Girdle (or Holy Zoonoro) of the Virgin Mary, a symbol of divine protection and intercession – represents restriction, similar to the social and cultural constraints placed on women (physical, emotional and symbolic) to which Walker herself made explicit reference. This layered meaning evokes both a physical boundary and a metaphysical realm, one that allegorises the ways that larger forces – hate, destruction, love, destiny, peace – tacitly shape daily life for women navigating a world defined by men.

Fig.22

C.R.W. Nevinson

Battlefields of Britain 1942

Oil on canvas

1220 x 1840 mm

Government Art Collection, 0/5

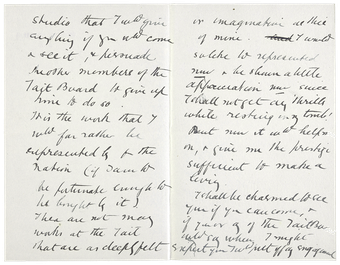

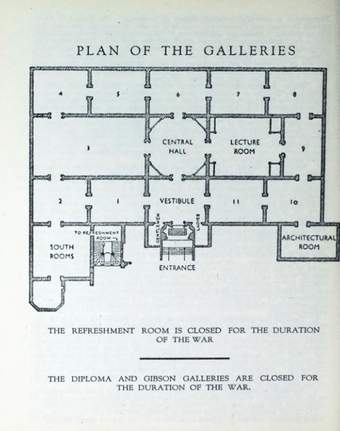

In 1942 Walker’s two ‘zone’ works were exhibited at the Royal Academy. They occupied two of the four display walls in the octagonal Central Hall alongside two war-themed paintings from the same year: C.R.W. Nevinson’s Battlefields of Britain (fig.22) and Louis Duffy’s Military Objectives (date unknown), a potentially allegorical painting now considered lost, with no surviving photographic documentation (figs.23–4).83 Together these works reflected the cultural and symbolic landscape of utopian and apocalyptic art in the early twentieth century, shaped by the dual forces of war and the fragile peace of the interwar years.

British art of this era was deeply imbued with Christian symbolism, intertwining themes of apocalypse and resurrection. For instance, Evelyn De Morgan’s First World War paintings, like Walker’s, combine Christian iconography with the female form to convey anti-war sentiment through spiritualist belief.84 The realm of the ‘zone’ – a liminal, in-between space – clearly united works displayed in the Royal Academy’s Central Hall in 1942. Nevinson’s Battlefields of Britain depicts a dream-like view from a fighter plane cockpit, merging clouds and distant countryside, inspired by John Gillespie Magee Jr’s sonnet ‘High Flight’. Written shortly before Magee’s death in 1941 and appearing widely in the press, the poem evokes the spiritual transcendence of flight and concludes with an image of touching the divine ‘face of God’.85 Excerpts were featured in the Royal Academy exhibition catalogue (see fig.24), reinforcing Battlefields of Britain’s themes of escape, spiritual elevation and the hope of resurrection amid wartime destruction.86

Fig.23

‘Plan of the Galleries’, from The exhibition of the Royal Academy, 1942. The 174th., exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1942

Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London

Fig.24

‘Central Hall’, from The exhibition of the Royal Academy, 1942. The 174th., exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1942 (missing text cut off on original scan)

Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London

There is no additional material related to this display in either Tate’s or the Royal Academy’s archive, so the circumstances in which Walker submitted The Zone of Hate and The Zone of Love to the Academy exhibition remain unknown, as do the critical and emotional responses of its audience. Had Walker intended the paintings to be hung alongside the works by Nevinson and Duffy? Had she envisaged them as part of a sentimental display that was clearly about war, death and Christian spirituality? What we do know is that Walker clearly wanted The Zone of Hate and The Zone of Love to be part of the Tate collection, of which such a prominent display may have been a prerequisite qualification. On 2 May 1946 she wrote to Rothenstein, ‘I am prepared to present to the Tate Gallery with its approval my 2 large & best works of my life the “ZONE OF HATE” and the “ZONE OF LOVE”.’ The Director responded, sharing the news that the Trustees had ‘accepted with gratitude’.87

Walker’s large classical allegorical decorations likely found acceptance in a major institution due to the prevailing genre hierarchy. After the Tate Board rejected some of her smaller works in 1947, a dispute arose between Walker and Rothenstein in 1948 over acquiring more of her art.88 On 23 October she reminded him, ‘You know I have been generous presenting the Tate Gallery with 2 large decorations’, and asked, ‘Don’t you think it is time you bought a picture of mine?’ Rothenstein replied on 1 November, acknowledging her ‘generosity’ but noting, ‘our collection now contains ten examples of your work … There can, therefore, be no question of any recent neglect on the part of the Tate to add to your representation here.’ Walker countered the next day, stressing that ‘every purchase of my work strengthens and enriches the sum of good pictures at the Tate Gallery’.89 The art critic Mary Sorrell might have agreed, for it was around this time, in 1947, that she wrote her Apollo article celebrating the long-overdue ‘recognition’ that she claimed Walker was now receiving. ‘Amongst artists to-day her work has no rival’, Sorrell writes, ‘Everything she paints bears the impress of her personality: of an artist who loves art for its own sake, and who, by her gifts and by the virtue of her long dedication to them, takes her place, at the age of eighty, as one of the greatest of living painters.’90

At the time of her posthumous, joint Tate Gallery exhibition with Gwen John and Frances Hodgkins in 1952, Walker’s ‘zone’ works were not included in the main exhibition but displayed alongside Nausicaa in the Sculpture Gallery.91 Evidently, regardless of her intention with these works at the Royal Academy in 1942, Walker not only navigated the constraints and opportunities of her time, but she also produced decorations – what she called her ‘masterpieces’ – that contributed to a broader dialogue about the role of art in times of crisis, becoming key pieces within the history of British art. While her ‘zone’ decorations were donated rather than purchased, by employing classical and Christian citations and painting them on a large scale, they aligned with history painting and were ultimately accepted. This approach, traditionally dominated by male contemporaries such as Augustus John, elevated her works beyond what institutions such as the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery still saw as the ‘lesser’ genres of portraiture, still life and landscape with which women were often associated, as Walker herself noted at the WIAC. Her strategic engagement with classical themes not only challenged gendered boundaries within the art world but also enhanced her standing within a significant national collection, a goal she had long sought to achieve.

A lasting legacy

Ethel Walker’s career stands as a testament to the persistence of women and the complexity of their roles in the British art world during the early twentieth century. Walker carefully navigated institutional barriers to gain recognition in an art world that often made it difficult for women to gain prominence. While she sought validation from institutional spaces such as the Royal Academy, it was the permanent public collections of the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery within which she strategically positioned her works.

Although my research has primarily focused on these institutions, further investigation is needed into Walker’s work and its broader collection across the United Kingdom. Currently, 119 of her works are held in 46 public collections, including Manchester Art Gallery, York Art Gallery, the Courtauld Gallery, London, the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, the Arts Council Collection and Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle. Moreover, in addition to the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery, Walker also expressed a desire to bequeath her work to Scottish institutions, reflecting her national identity and aspirations for a legacy that extended beyond England.92 These ambitions, along with her election as President of the WIAC and her insistence on competing on equal terms with her male contemporaries, reflect her determination to assert her place within a canon of British art that was developing in the early twentieth century. The role of private collectors in the advocacy and dissemination of her work also warrants further study.

Walker’s legacy is not only one of artistic achievement but also of navigating the cultural and institutional constraints that shaped women’s artistic careers in her time. Nausicaa has recently been displayed in two exhibitions at Tate Britain: Queer British Art (2017) and Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920 (2024).93 Her decorative works held by the museum were the focus of a spotlight display as part of Tate Britain’s new collection rehang in 2023. The same year, Piano Nobile gallery devoted its stand at London’s Frieze Masters art fair to Walker. In this moment of renewed interest, her work offers valuable insights into how women artists sought to redefine the visual and intellectual narratives of the early twentieth century. By examining Walker’s oeuvre in relation to the institutions that both included and excluded her, we can better understand the broader historical patterns that shaped interwar British art and the evolving contexts in which her work is now placed.