Fig.1

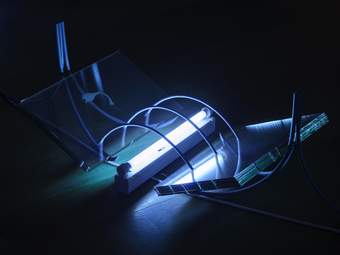

Hamad Butt

Transmission 1990

Glass, steel, ultraviolet lights and electrical cables

Dimensions variable

Tate T15512

© Jamal Butt

Introduction

Fig.2

Hamad Butt

Transmission 1990 (detail)

Courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Photo © Ros Kavanagh

In 2023 Tate Britain rehung its free collection display for the first time in ten years. From one room, an eerie blue glow emanates from the edges of a dark curtain. Entering the room, gallery visitors are confronted with a circle of nine sculptures (fig.1). An ultraviolet spine courses through each one, illuminating glass pages resting on wire frames. On the one hand, this strange sight draws the viewer in: to find the source of the light, to take a closer look at the glass pages, to circle the ritualistic arrangement of sculptures in the hope of interpreting any message they might offer. On the other hand, the installation also invites caution: the ultraviolet rays risk damaging the viewer’s eye, requiring the provision of safety goggles; the wire frames resemble mosquitoes or flies, carriers of disease that might penetrate the human body or feed off its waste; finally, on the glass pages of each sculpture is etched the image of a triffid (fig.2), a fictional plant-monster that feeds on humans, taken from John Wyndham’s apocalyptic 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids. Statements printed onto the walls call to mind eroticism (‘seductive’), danger (‘contagion’, ‘invasions’) and religion (‘books of fear’, ‘blind faith’);1 the work’s first iteration also featured Fly-Piece 1990/2024 (fig.3), a wall-mounted vitrine containing maggots that moulted and metamorphosed into flies before dying, as well as a video of a triffid. Titled Transmission, the installation was produced by the British artist Hamad Butt in 1990. It was made two years after Section 28 was passed to prohibit ‘the promotion of homosexuality’ by local councils, at the height of the AIDS epidemic in Britain, and in the context of ever-accelerating global flows (or ‘transmissions’) of ideas, goods and people. Transmission invites us to consider the roles of fear and desire, repulsion and attraction, in responses to the seemingly unfamiliar or unknown: to queer and racialised ‘others’ as much as viruses and carnivorous monsters.

Fig.3

Hamad Butt

Fly-Piece 1990/2024

Wall-mounted wood and glass vitrine, gold paint, paper and live flies

1670 x 1064 x 92 mm

Courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Photo © Ros Kavanagh

Transmission (Tate T15512) entered Tate’s permanent collection in 2019, having been presented as a gift by the artist’s brother, Jamal Butt. It joined Butt’s second and final major installation work, Familiars 1992 (Tate T14779), which had entered the collection as a gift in 2014. Familiars is an installation of three sculptures made of glass containing iodine, bromine and chlorine, substances which, depending on concentration, can be harmful to the human body. As with Transmission, these sculptures both captivate and repel the viewer. Their forms invite us to interact or play with them, and yet doing so would shatter the glass vessels, allowing the substances within to leak out. Familiars plays on similar tensions and anxieties to Transmission: a dynamic of containment versus release, control versus surrender.

At the time of his death in 1994, Butt’s work was championed by curators, critics and art historians, including the Founding Director of the Institute of International Visual Arts (iniva), Gilane Tawadros, the art critics Jean Fisher and Stuart Morgan, and the art historian Kobena Mercer.2 In 2014, at Fisher’s invitation, 61 individuals signed a letter to Tate endorsing the acquisition of Familiars, expressing ‘unreserved support’ for the proposed acquisition and emphasising Butt’s ‘unprecedented’ and ‘exceptional’ practice by detailing his interests and achievements.3 In a short text written to make the case for the acquisition of Familiars contained within the work’s acquisition files in Tate’s Gallery Records, Zoé Whitley, a curator at Tate between 2013 and 2019, echoes this sentiment, noting that Butt is ‘an important yet under-recognised figure in 1990s British art’.4 The Tate rehang in 2023 marked the first display of Transmission since the exhibition Zerozerozero: British-Asian Cultural Provocation at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1999. Meanwhile, a 2018 display of Familiars at John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, was the installation’s first since 1995, when it was shown as part of Rites of Passage: Art for the End of a Century at the Tate Gallery.5 With the acquisition and display of Butt’s work at Tate and the opening of Hamad Butt: Apprehensions at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (IMMA), in December 2024, Butt’s work is more widely visible than at any point since his death.

As the artist and art historian Eddie Chambers reminds us, important yet under-recognised artists are particularly vulnerable to exaggerated narratives of loss and rediscovery – the kind of story of which the art establishment is so fond.6 The arbiters of such narratives, Chambers adds, tend not to reflect on, much less articulate, the reasons why certain artists are ‘lost’ or unrecognised (at least by the mainstream) in the first place. The temptation to cast artists in this way – as once ‘lost’ or ‘forgotten’, now ‘found’ or ‘rediscovered’ – is perhaps even more prevalent in the context of the current emphasis on ‘diversifying’ public art collections and exhibition programmes, which has generally entailed the display and sometimes acquisition of works by queer, racialised and women artists, among others.7 The critic Adrian Searle warns against this temptation, writing that Butt’s solo show at IMMA ‘is no rediscovery of a lost artist’.8 Yet this narrative is evident in recent coverage of the artist. In a review for the Guardian, for example, Elizabeth Fullerton asks, ‘why haven’t we heard of Butt before?’ and attributes Butt’s ‘lack of visibility’ to ‘the complex and hazardous nature of his works’ and to his death.9 Similarly, Kabir Jhala implies that the artist is ‘not well known to contemporary audiences’ because of his ‘contract[ing] AIDS’ and ascribes Butt’s obscurity to ‘a stark divide in fortune’ from his better-known contemporary Damien Hirst.10 Such commentary skirts the issue of to whom, exactly, Butt has been lost, and forecloses a more nuanced discussion of why.

In light of the pervasiveness of art world narratives of loss and recovery, and the subtle reappearance of these narratives in writing about Butt, here I regard the idea of Butt’s ‘rediscovery’ with suspicion. To echo Stuart Hall’s comments on the archive, no acquisition ‘arises out of thin air’.11 Acquisitions, like archives, have a ‘“pre-history”, in the sense of prior conditions of existence’.12 The Transforming Collections project of which this research is a part is particularly interested in these pre-histories, in precisely which voices are present and absent from public art collections and archives in Britain and why.13 In the case of Familiars, the first of Butt’s works to enter the Tate collection, this pre-history is not contained within acquisition files or museum databases. What I find elsewhere is that Familiars was proposed and turned down for purchase in 1995 and 1997 before it entered the collection as a gift in 2014. This invites the question of why Butt’s work was initially declined and why it was later acquired. Such investigations, as the art historian Richard Hylton has argued, are part of the work of decolonising art history, seeking as they do to challenge the museum sector’s history of exclusion and tokenism.14

My research interrogates this case first by reconstructing a pre-history of the acquisition of Familiars. This approach is informed by critical theoretical perspectives on institutions and their records, taking into account the scarcity of official documentation to draw on and the knowledge that what is there can only ever tell part of the story. The historian Achille Mbembe invites us to consider the partial nature of records as collections of data having been judged to be archivable, or worth archiving, by some authority or organising power, however diffuse.15 Meanwhile, scholars such as José E. Muñoz and Gavin Butt attest to the value of less conventional, ‘visible’ or ‘rigorous’ forms of evidence such as ‘gossip, innuendo, fleeting moments’ and ephemera (Muñoz), ‘unverified by some authorised body or mode of validation’ (Butt), for their capacity to attest to minoritarian (especially queer) experiences, sensibilities and worlds.16 In my reconstruction of the pre-history of the acquisition of Familiars, I follow rumours and memories of those around Hamad Butt and at Tate, corroborating and challenging these with findings from Butt’s recently catalogued archive at Tate, compiled and donated by his brother Jamal, as well as Jamal’s personal archive.17 I compare this pre-history with the acquisition of works by other contemporary artists in Britain that were prioritised for purchase earlier, including works containing materials that are hazardous or challenging to store and display. In so doing, my research complicates the rumour – tentatively offered by those close to Butt, and increasingly part of the narrative of his work – that Familiars was initially rejected for acquisition for its toxic materials alone. I suggest that Familiars was deprioritised for acquisition in the 1990s because of a complex web of factors, not only Butt’s premature death but also the shifting institutional currencies of work by queer and racialised artists, particularly abstract work. Indeed, Butt’s work is not easily legible within the aesthetic parameters of institutionally successful artists of the global majority at the time – namely, the recognisable representation of their ‘identities’.

Familiars at Tate: A pre-history

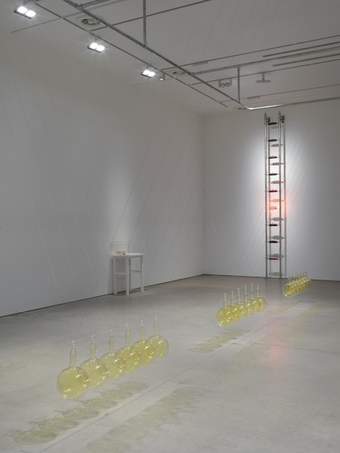

Familiars was co-commissioned by Stephen Foster, Director of Southampton’s John Hansard Gallery (1987–2017), where Familiars was first displayed in 1992; and Lawren Maben, the founder of Milch Gallery, London, where Transmission and Familiars were exhibited separately in 1992.18 The work consists of three sculptures. All are made from borosilicate glass and contain common halogens that are toxic at higher concentrations than Butt used in these works. Cradle comprises up to 18 glass globes suspended from the ceiling, each stained yellow from the chlorine gas held within (fig.4); Hypostasis consists of three prongs made from steel and glass and containing bromine, bowed slightly and held down by steel wire, as if poised to snap straight and shatter (fig.5); and Substance Sublimation Unit takes the form of a brittle ladder, each rung housing iodine (fig.6).

Fig.4

Hamad Butt

Familiars (‘Cradle’) 1992

Vacuum-sealed glass, chlorine gas

Dimensions variable

Tate T14779

© Jamal Butt

Fig.5

Hamad Butt

Familiars (‘Hypostasis’) 1992

Vacuum-sealed glass, liquid bromine and steel

Tate T14779

© Jamal Butt

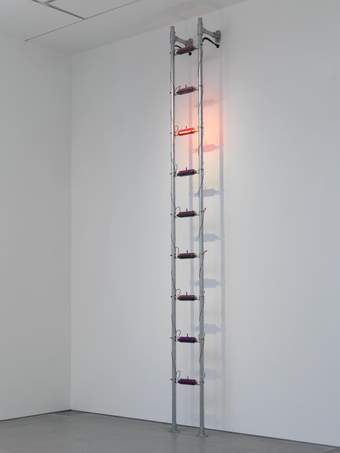

Fig.6

Hamad Butt

Familiars (‘Substance Sublimation Unit’) 1992

Vacuum-sealed glass, crystal iodine and steel

Tate T14779

© Jamal Butt

The sculptures call to mind Butt’s interest in and knowledge of science, cultivated during his undergraduate studies in biochemistry and evidenced in his writings.19 For example, Cradle replicates Newton’s Cradle, an object comprising swinging spheres that evidences principles of momentum and energy, while Substance Sublimation Unit demonstrates the process of sublimation, according to which substances transform from solid into gas. Yet these sculptures also evoke the spiritual and supernatural. ‘Hypostasis’ can denote spiritual principles of fundamental states or substances, as in Greek philosophy, and in Christian theology it refers to the Holy Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, reflected in the sculpture’s three prongs. The ladder form of Substance Sublimation Unit echoes ‘Jacob’s Ladder’, which appears in a dream in the biblical book of Genesis and ascends to heaven, or the ‘holy ladder of perfection’ mentioned by the sixth-century monk John Climacus.20 As Zoé Whitley notes about Familiars in her collection text – short accounts of an artwork created following its acquisition and published on Tate‘s website – sublimation recalls the process of transubstantiation, whereby bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ.21 Butt was interested in the junctures and disjunctures between scientific, philosophical, religious and magical thinking; the hierarchies and porous boundaries between the so-called rational and irrational. He read widely in the history and philosophy of science and attended scientific conferences. His notes reveal a fascination for the now overlooked presence of esoteric and religious thinking in the history of science, including alchemy and ‘Maxwell’s demon’, a thought experiment in physics intended to further understanding of the second law of thermodynamics.22

Butt’s undergraduate thesis – written during his time as an art student at Goldsmiths between 1987 and 1990, and as he prepared Transmission – indicates the political nature of his interest in science at this time, shaped as it was by the AIDS crisis and accelerated globalisation as the world hurtled towards the new millennium. In the thesis, Butt explores the physiological experience of fear in response to perceived danger and the subsequent ‘apprehension’ or ‘misapprehension’ of this experience through language. He writes:

Apprehensions take hold of what is fearful by casting it in the name of a particular other. Apprehension is not comprehension but slides into that realm by the conviction … of the grasp.23

Butt proposes that cultural discourses on otherness fill the gap between physiological experiences of fear and our understanding or ‘apprehension’ of these experiences. Fear, then, comes to be directed at society’s imaginary ‘others’.24 Butt goes on to discuss ‘fear of disease’ and AIDS, theorising that this fear is worked through ‘by the transcription of contamination upon the body of others’.25 Citing the philosopher Michel Foucault and communications scholar Martha Gever, Butt highlighted the role played by visual media such as photography and television in demarcating and constructing these ‘others’ as contaminated, particularly the feared figures of the ‘homosexual’ and the racialised ‘foreigner’.26 In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the AIDS epidemic surfaced cultural fears about increasing global contact, including cultural and racial ‘mixing’, the expanding reach of media and communications technologies, and atmosphere pollution.27 Keenly aware of this widespread homophobia, xenophobia and racism, Butt states that ‘one of the risks in representing AIDS is the identification [of] the others of the social order, the others that the presumed healthy whole community can continue to “scapegoat”’.28 Thus, Butt’s task was to find a means of conjuring the fear of the other – the virus that threatens to penetrate the body’s borders and compromise its supposed wholeness – without offering up an image of othered figures for the viewer to ‘scapegoat’. The sculptures that make up Familiars and the substances that threaten to escape their vessels and infiltrate our bodies thus conjure this fear of contamination through abstraction rather than figuration or documentation, asking us to focus on the experience of danger from which scapegoating discourses emerge.

In the wake of its exhibitions in the early 1990s, Familiars was well received by critics. In his review, Stuart Morgan attends to the conceptual, art historical and experiential aspects of the work, comparing Butt’s ‘industrial imagery’ with that of Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp, and seeing in Familiars an invitation to reflect on the vulnerability of the body and the precarity of existence.29 Writing later in the decade, Jean Fisher praises Butt’s ‘profound reflection on the conditions of contemporary existence’.30

When Butt passed away in September 1994, his brother Jamal took responsibility for his estate. Jamal, a pharmacist, was unfamiliar with the workings of the art world, but Butt’s friend and former teacher at Goldsmiths, the art historian Sarat Maharaj, advised Jamal to place the work in a collection for its preservation for future generations.31 As it happened, Familiars had been chosen for display in the exhibition Rites of Passage: Art for the End of the Century at the Tate Gallery, which was due to open in June 1995. The exhibition was curated by Morgan, a friend and supporter of Butt’s, who had seen Familiars at John Hansard Gallery in 1992, and Frances Morris, who worked at Tate between 1987 and 2023. Butt’s friends, the artists Diego Ferrari, Dan Hays and Angela Bulloch, helped prepare Familiars for display in Butt’s absence.32 One month into Rites of Passage’s run, in early August 1995, visitors to the Tate Gallery were forced to evacuate after a crack appeared in the inner glass of one of the borosilicate rungs of Substance Sublimation Unit, releasing the potentially toxic iodine contained within. As the glassblower Colin Smith suggests in a conservation report written shortly after the incident, the crack was likely caused by the inner glass coming into close contact with the ‘central heating element’ inside it.33 This episode has been absorbed into the myth of Familiars and its rejection for purchase by Tate in 1995. Elizabeth Fullerton, for example, attributes Butt’s ‘lack of visibility’ to the ‘hazardous’ materials that the artist favoured.34 The writer and scholar Kevin Brazil reports in an essay that Stephen Foster, who worked closely with Butt and his brother over the years, believes that Tate’s refusal to acquire Familiars was because of ‘a worry about “how to preserve the toxic chemicals”’.35 Butt’s brother has echoed this narrative in conversation.36 This speculation is bolstered by the fact that Tate acquired other works included in Rites of Passage in 1995, such as Mona Hatoum’s 1993 sculpture Incommunicado (Tate T06988) and several installations by the artist Mirosław Bałka (for example, Fire Place 1986, Tate T06960). That same year, however, when Familiars was proposed for acquisition by Butt’s family, it was rejected.

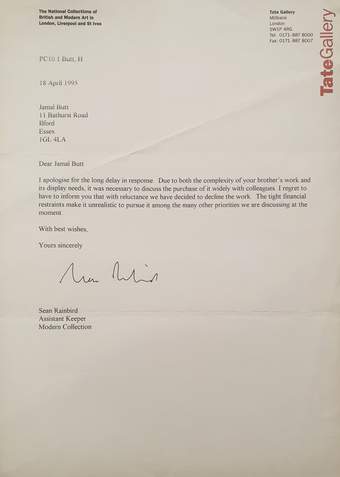

Fig.7

Letter from Sean Rainbird to Jamal Butt, 18 April 1995

Tate Archive, TGA 201919/1/2/23

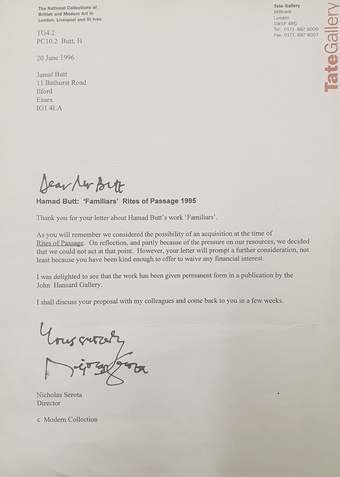

This episode adds drama and intrigue to Butt’s story, corresponding with the myth-making of other young contemporary artists at the same time. David Lister of the Independent discussed the incident in relation to a broader tendency towards ‘hazardism’ – the use of hazardous materials in art or the appearance of health and safety risks to visitors – in the work of artists including Damien Hirst, Carlos Capelan and Rebecca Horn.37 Butt’s archive, however, complicates the idea that Tate refused to purchase Familiars because its curators were, in Jamal’s words, ‘spooked’ by the incident at Rites of Passage. The recently catalogued archive, compiled by Jamal and donated to Tate in 2019, contains correspondence, research notes, exhibition ephemera, sketchbooks and appointment books.38 Correspondence between Jamal and Tate reveals that Familiars was informally proposed and rejected before Rites of Passage opened (fig.7). A letter dated 18 April 1995 from Sean Rainbird, a curator at Tate from 1987 to 2006, notifies Jamal of the decision to decline an earlier proposal because of ‘tight financial restraints’ and ‘the many other priorities’ being discussed at that time. The letter also notes that ‘the complexity of the work and its display needs’ necessitated a wide discussion.39 These factors are reiterated in a subsequent letter following another, unrecorded proposal for Familiars to be purchased. Writing to Jamal on 20 June 1996 in response to this undocumented proposal, Nicholas Serota, Director of Tate from 1998 to 2017, remembers that Familiars had been rejected the previous year ‘partly due to pressure on [Tate’s] resources’, but the proposal would be reconsidered now, ‘not least because [Jamal had] been kind enough to offer to waive any financial interest’ (fig.8). Even with this concession, this second proposal was also turned down. There are no records of this rejection in the archive at Tate, but Jamal’s records contain a letter from Serota in February 1997 stating that he hopes to provide an answer about the possibility of the acquisition of Butt’s work ‘within the next month or so’.40 A letter to Jamal from Rainbird, dated 31 March 1998, confirms that the ‘earlier decision to decline the works still stands’, and suggests Jamal approaches IMMA for acquisition.41 Serota writes again to Jamal on 26 May 1998, expressing his hopes ‘that the Contemporary Art Society has been able to assist in placing Hamad’s work in a regional gallery’.42

Fig.8

Letter from Nicholas Serota to Jamal Butt, 20 June 1996

Tate Archive, TGA 201919/1/2/23

Familiars, then, was first rejected before the incident at Rites of Passage, which has become part of the work’s mythology. The incident is unlikely to have affected the outcome of subsequent proposals, not only in light of Serota’s apparent readiness to consider the work after 1995 but also because the risk to visitors presented by Familiars was deemed by the museum to be relatively low. Safety tests conducted before the exhibition by Jamal – a qualified chemist – stress that the chemicals are diluted to a degree that they pose little danger.43 A note from the conservator Karin Hignett in the acquisition file explains that as soon as it hits cold air, iodine solidifies to inert powder (a form in which it is not particularly hazardous). The decision to evacuate gallery visitors in the event of an issue with Familiars was made in advance of the exhibition as a standard mitigation for managing health and safety risks in public spaces.44 The drama and intrigue of this episode should not overshadow the fact that the work was not considered too risky to display or conserve.

At the time of Jamal’s initial proposal, Tate had several works in its collection that presented similar issues to Familiars, and the museum found ways of mitigating risk. For example, Ballet of the Woodpeckers 1986 (Tate T06551) by the German artist Rebecca Horn, which was purchased in 1991, contained mercury. Being highly toxic, the mercury was replaced with silver foil for safety reasons when it entered the collection.45 Two of Hirst’s formaldehyde works – Mother and Child (Divided), original 1993, exhibition copy 2007, (Tate T1275) and Away from the Flock 1994 (Tate AR00499) – entered the collection in 2007 and 2008 respectively, the years of the Turner Prize retrospective exhibition at Tate Britain (Hirst had won the prize in 1995). Formaldehyde is more hazardous than any of the substances contained within Familiars, with works containing formaldehyde requiring handling by certified specialists.46 The fact that Tate’s collection contains several such works suggests that it is not the case that Familiars was simply too dangerous, challenging or complex for the gallery to acquire. Deborah Cane, Conservation Manager at Tate, states that, with the exception of art containing radioactive material, a work would not be rejected for acquisition on account of its materials or risks. Rather, it is a question of figuring out how to manage these risks.47 Ultimately, in the case of Butt’s work, risks were managed. Familiars went through extensive examination and testing by Tate’s conservation team, who eventually replaced the borosilicate glass with the more heat-resistant quartz.48 With Transmission, the vitrines containing fly larvae were not acquired, along with the video.49

All of this indicates that Familiars was not too risky to consider for acquisition, but that it was not at that time a priority for Tate. So what were the museum’s ‘priorities’ mentioned in the letter to Jamal Butt? Answering this question requires a more detailed look at Tate’s acquisitions of contemporary British art and the broader contexts for artistic production in Britain in the 1990s. For artists of colour working within this context, institutional success partly hinged on making playful or ironic allusions to one’s racial or cultural identity, particularly in relation to ‘Britishness’.

Contemporary British art of the 1990s

In a letter of 1997 to Kerry Brougher – then freshly appointed as the new director of Modern Art Oxford – Stuart Morgan discusses Tate’s potential acquisition of Familiars, which he hoped Brougher might display in the meantime (although such a display was never realised). Morgan notes that ‘Negotiations move slowly’.50 While Tate prevaricated over its potential purchase of Familiars, works by other artists of Butt’s generation entered the collection relatively quickly. For example, Tate purchased Damien Hirst’s 1991 sculpture Forms Without Life (Tate T06657) in 1992. Other artists of Butt’s generation whose work was acquired by Tate throughout the decade include Chris Ofili, Yinka Shonibare and Steve McQueen, to whom I will return shortly.

Many of these artists were and continue to be associated with what was alternately referred to as ‘New British Art’, ‘BritArt’ or, most commonly, the ‘Young British Artists’ (YBAs). Like Butt, several of them studied Fine Art at Goldsmiths College in the 1980s and 1990s, including Hirst and Shonibare; others, like Ofili and Tracey Emin, studied at the Royal College of Art and elsewhere. While the practices of the YBAs were highly divergent and they worked across a range of media, much of their work is characterised by an interest in the abject, shock and irony. The 1988 exhibition Freeze!, organised by Hirst and fellow students at Goldsmiths, is generally considered to mark the beginning of the YBAs’ rise to fame. Group shows including Minky Manky at South London Gallery and Brilliant! At the Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis, in 1995–6 ‘cemented’ contemporary British art as a cultural phenomenon.51

Fig.9

Visitors at the opening of Familiars at Milch Gallery in London, 1992

Tate Archive, TGA 201919/8/10

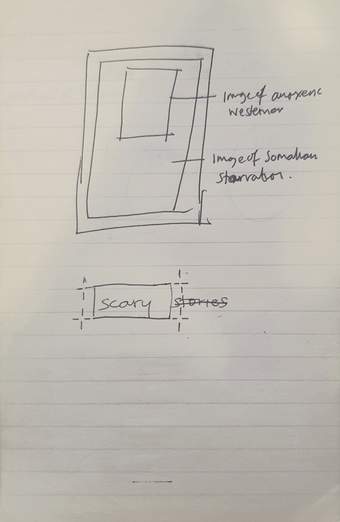

Butt’s work shares certain subject matter and tactics with the wider YBA grouping. Familiars is a case in point, addressing the body’s vulnerability and incorporating toxic materials. The writer and curator Gregor Muir remembers the 1992 opening of Familiars at London’s Milch Gallery as a ‘typically crazed Milch affair, with people’s anxiety growing as they found themselves pressed ever nearer the threatening glass balls’ (fig.9).52 Butt’s notebooks in Tate’s archive show sketches for other unrealised, abrasive holographic works in keeping with the YBAs’ fascination for the abject and for confrontational tactics. One incorporates an image of the writer Salman Rushdie, then the subject of recent and highly public assassination threats for his controversial novel The Satanic Verses (1988), with a branded forehead; another juxtaposes an ‘image of [an] anorexic westerner’ and one ‘of Somalian starvation’ (fig.10); and others merge explicit sexual imagery with pictures of the British boyband Take That.53 One factor distinguishing Butt from these artists, however, is aesthetic. In his 1997 letter to Brougher, Morgan describes Tate’s consideration of whether or not to purchase Familiars in terms of ‘an aesthetic decision and a storage question rolled into one’. Perhaps this was speculation; or perhaps Morgan, who had recently worked with Frances Morris on the 1995 Tate exhibition that included Butt’s work, was privy to conversations that were not recorded. Regardless, Morgan’s comment prompts us to consider the aesthetics of Butt’s work as a factor in Tate’s decision not to acquire the work in the 1990s.

Fig.10

Hamad Butt, page from artist’s notebook, undated

Tate Archive, TGA 201919/3

Illustrative here is a brief comparison between Butt’s work and the work of Ofili, Shonibare and McQueen. In 2014 Eddie Chambers referred to these artists as a ‘triumphant triumvirate’ for their institutional success as Black artists since the 1990s.54 All three saw their work acquired by Tate during this period. McQueen’s short film Bear 1993 (Tate T07073) was acquired in 1996 (fig.11). Tate purchased many of Ofili’s works on paper in the late 1990s, including Double Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars (Tate T07345), produced in 1997 and purchased the same year (fig.12). Shonibare’s installation The Swing (after Fragonard) (fig.13, Tate T07952) was purchased in 2001, the year it was made. Further purchases of works by these artists have followed to the present day. As Chambers argues, these artists were (and are) talented and ambitious. But their institutional success, he writes, is also owed to their relationship to the particular political and cultural context of Britain in the 1990s.

Fig.11

Steve McQueen

Bear 1993 (film still)

16 mm, black and white, shown as video, projection, 9 min 2 sec

Tate T07073

© Steve McQueen, courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery, London

The early years of the decade witnessed a growing dissatisfaction with the long-serving Conservative government, reflected in the popularity of Britpop artists such as Oasis, whose debut album was released in 1994, and Blur, who released Parklife to acclaim the same year.55 Such artists voiced feelings of disenfranchisement owing to years of Conservative domination. Several made music that reflected on or celebrated their working class backgrounds and were therefore considered emblematic of growing social and economic mobility.56 The flurry of interest in the YBAs from galleries, collectors and media pundits is tethered to this context. Their work was seen as a challenge to the establishment; they cultivated a ‘low-culture’ aesthetic, often incorporating elements of mass media culture; and some of these artists developed celebrity personas that were linked to their working class backgrounds (Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin are two examples). Such was the cultural currency of contemporary British art that, along with Britpop, it would be exploited by New Labour’s ‘Cool Britannia’ agenda, the party’s attempt ‘to rebrand Britain as a nation of creative hip young things’.57 The sociologist Jason Arday defines the ‘Cool Britannia years’ in terms of a renaissance of the ‘swinging sixties’, a ‘renewed … sense of national pride’ in Britain’s cultural and sporting achievements, and the emphasis on cosmopolitanism and multicultural ‘inclusion’ in New Labour politics.58

Fig.12

Chris Ofili

Double Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars 1997

Oil paint, acrylic paint, printed paper, glitter, map pins, polyester resin and elephant dung on canvas

2440 × 1830 mm

Tate T07345

© Chris Ofili, courtesy Victoria Miro, London

Multicultural inclusion also manifested on a global stage. With the acceleration in the flow of goods, ideas and people that intensified throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, contemporary art became a global commodity. Curators and collectors were increasingly interested in art by artists of the global majority. The many international mega-exhibitions that arose in the 1990s sought to platform artists seen to represent ‘Africa’ and elsewhere.59 Kobena Mercer noted in 1999 that in this new ‘global market of multicultural commodity fetishism’, difference became hyper-visible, while also being detached from political empowerment.60 Describing the British context the following year, the artist and writer Rasheed Araeen notes the effects of the institutionalisation of concepts such as ‘hybridity’ and ‘exile’, which were drawn from postcolonial theory and developed through analyses of literature rather than art and art institutions. To Araeen’s mind, the popularity of such concepts among curators and artists has produced an unbalanced state of affairs in which ‘non-white artists must enter the dominant culture by showing their cultural identity cards’, by ‘display[ing] the signs of their Otherness’.61

It was in this context that Tate was prevaricating over its purchase of Familiars, and that Ofili, Shonibare and McQueen emerged. The work of each of these artists contains Black subjects, or visual markers that suggest Blackness. Their work was lauded by majority white critics at the time for different reasons, including for not making ‘an obvious issue of … race’ (McQueen), for offering up visually pleasing manifestations of ‘cultural hybridity’ (Shonibare) or else for their supposed ‘political incorrectness’ (Ofili).62 McQueen’s film Bear depicts two Black men wrestling; their sparring bodies, glistening with sweat, are shown in close detail. The subject of Double Captain Shit, meanwhile, is a Black superhero invented by Ofili, chest and torso exposed beneath a bodysuit. Ofili has described this fictional figure as a wry response to portrayals of Black masculinity in blaxploitation films and comic books, most notably the American superhero Luke Cage, upon whom Captain Shit is partly based. Ofili has said: ‘My project is not a PC [politically correct] project … I’m trying to make things you can laugh at. It allows you to laugh about issues that are potentially serious.’63 The board note – an internal document written by curators and presented to its Board of Trustees when an artwork is being proposed for acquisition – echoes this, framing the superhero as ‘an ironic comment on the way in which non-blacks often perceive black people’, and the use of dung as ‘an ironic comment on [Ofili’s] status as a British Mancunian of Nigerian descent’.64 Finally, Shonibare’s The Swing (after Fragonard) presents the viewer with a headless female mannequin wearing ‘Dutch wax print’ cotton textiles (or ‘bright African print fabric’, as Tate’s online collection text puts it), posed to echo the sitter in Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s painting The Swing c.1767–8 (Wallace Collection, London), a symbol for a white, European history of art. The board note stresses the sculpture’s relationship to ‘race, class and heritage’ in connection with Britishness without elaborating on this relationship, stating that the work ‘would find a context for display most readily at Tate Britain owing to its examination of “Britishness” and its engagement with the history of art’.65

Fig.13

Yinka Shonibare

The Swing (after Fragonard) 2001

Mannequin, cotton costume, two slippers, swing seat, two ropes, oak twig, artificial foliage

3300 x 3500 x 2200 mm

Tate T07952

© Yinka Shonibare, courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

For his part, Butt stated in 1985 that he ‘won’t deny’ his ‘Asian … cultural background … but I won’t speak for it, in the same way I don’t primarily regard myself as a gay artist’, although he had previously exhibited in Work by Gay Women and Men at Brixton Art Gallery and at the LGBT bar The Fallen Angel, both in London, in 1983 and 1984 respectively.66 Indeed, in the 1990s his work was frequently compared with that of Ofili, Shonibare and McQueen for diverging from the collectivist political projects that emerged among artists of colour in 1980s Britain and for their reticence towards the politics of identity.67 Yet Butt’s response to the state of affairs described by Chambers, Mercer and Araeen – wherein artists of colour are expected to display their ‘identities’, but in ways that register as ironic, or ‘politically incorrect’, or in relation to Britishness – is distinct from the approaches taken by McQueen, Ofili and Shonibare. The art historian Alice Correia has drawn out Butt’s references to Pakistani heritage in his work: she refers to his notes and sketchbooks to argue that Transmission’s circle of books and bookrests recall a Qur’anic reading circle and stands for the Qur’an, and that the arch of Hypostasis is reminiscent of Islamic architecture.68 But these references are more abstract and less widely recognisable than those seen in work by McQueen, Ofili or Shonibare. Absent are McQueen’s jostling Black bodies, Ofili’s irony or Shonibare’s references to European art history: Jean Fisher celebrated Butt’s work precisely because its concerns lay ‘beyond the limiting myths of national identities’, a quality that positioned his work in an art discourse that ‘receive[d] little institutional support’.69 There is also the difficulty of Butt’s work more generally: as Sarat Maharaj writes, Butt’s ‘subtlety and the deliberate opacities and obscurities of his work must have baffled quite a lot of people.’70

Butt’s practice did not fit the recognisable parameters for institutional success for emerging artists of colour at that time. Beyond his premature death, or the potential challenges of storing and displaying his work, this fact likely contributed to his marginalisation in the 1990s. Arguably, too, the parameters I have discussed remain in place today, as many artists and art historians have reiterated.71 In that case, why did Familiars finally enter the Tate collection in 2014 and, even then, only as a gift?

Why the 2010s?

One of several reasons Familiars was acquired in 2014 relates to a shift in Tate’s curatorial team in the second half of the 2000s. Ann Gallagher, Frances Morris and Andrew Wilson are three important figures in this shift. In 2005 Ann Gallagher joined Tate from the British Council, in the role of Curator (Head of British Art from 1900).72 In 2006 Morris, who had been a curator at Tate since 1987 and Head of Displays at Tate Modern since 2000, was appointed Director of Collections (International Art), and Wilson joined Tate as Curator of Modern and Contemporary British Art.73 Gallagher and Morris presented a new acquisitions policy to Tate Trustees in 2007, although the contents of this are not publicly available.74 Of course, a shift in policy would not have been possible without the prior work of the many artists, scholars and cultural workers drawing attention to the overrepresentation of white male artists in public art collections and art history curricula, and to the work of artists of the global majority.75 But at Tate, as Jamal recalls, Morris, Gallagher and Wilson played a role in the eventual acquisition of Familiars.76

Fig.14

Sunil Gupta

Lisa and Emily, London 1984

Photograph, inkjet on paper, printed 2018

500 x 330 mm

Tate P82137

© Simryn Gill

The expansion of Tate’s collection of modern and contemporary British art largely came to fruition from the late 2000s onwards. Many of the works acquired during this time were by artists of colour active since the 1980s, whose politicised practices had been marginalised by the ‘regressive localism’ and ‘art world globalisation’ that surrounded the YBAs in the 1990s.77 On apparently exceptional occasions, work produced in the 1980s and 1990s by this large and varied selection of artists entered the collection prior to the late 2000s, including two 1985 works by Sonia Boyce in 1987, a 1991 painting by Lubaina Himid in 1995 and several 1980s and 1990s works by Donald Rodney in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, the bulk of acquisitions – including further works by Boyce, Himid and Rodney – have occurred from the end of the 2000s onwards. In 2008 Tate acquired a 1987 work by Keith Piper; in 2009, by the Black Audio Film Collective and Himid; in 2013 and 2014, by Ingrid Pollard, Eddie Chambers and Chila Kumari Burman; in 2015, by Sunil Gupta; in 2016, by Rotimi Fani-Kayode; in 2018, by Sutapa Biswas and Isaac Julien; and in the years that have followed, further acquisitions of work by these artists and others. Much of the other work by artists of colour that Tate acquired during this time displays Black or brown figures, often in a documentary mode, lending itself to identity-based readings. These acquisitions were also the result of a strategy to expand Tate’s photography collections.78 This includes photographs taken in the early 1990s by Anthony Lam, Jagtar Semplay, Faisal Abdu’Allah, Ajamu X and Gupta (fig.14), acquired between the years of 2015 and 2021; and photography from earlier periods, such as by Raphael Albert, Bandele ‘Tex’ Ajetunmobi, James Barnor and Dennis Morris, dating from the 1950s to the 1970s and all presented to Tate in 2016.

Another factor that shaped the timing of the acquisition of Familiars is the ascendency of ‘queer art’ as a category over the past decade or so. The year 2017 can be considered a watershed in the story of queer art’s popularity in Britain. It marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act, which permitted ‘homosexual acts between two consenting adults over the age of 21’ in England and Wales. The year also witnessed several exhibitions and programmes that explicitly tied themselves to queer subjectivities, experiences and histories, including Queer British Art 1867–1967 at Tate Britain, Coming Out: Sexuality, Gender & Identity at the Walker Gallery, National Museums Liverpool, and Prejudice and Pride, a research project at the National Trust. This phenomenon is not restricted to Britain. For example, 2017 also saw the opening of Spectrosynthesis: Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Taipei, which has seen two further iterations at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre in 2021 and Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun Contemporary in 2023.

In its 2019–20 annual report, Tate announced its intention to acquire more works by LGBTQIA+ artists, as well as ‘women … minority artists and artists of colour’, in the wake of the success of Queer British Art.79 In the preceding decade, the museum developed public programming such as Queer and Now festival and the Queer Walk Through British Art, and published A Queer Little History of Art by Alex Pilcher, then a web developer at Tate.80 Its acquisitions during this time include the 1980s and 1990s documentary photography of Fani-Kayode, Gupta and Ajamu, Kutlug Ataman’s 1999 four-channel video installation Women Who Wear Wigs (Tate T13256) and photographs documenting the lives of LGBTQIA+ South African people, by the South African artist Zanele Muholi. Andrew Wilson has stated that there was a sense that the acquisitions of Familiars, Transmission and Butt’s archive would complement other purchases of queer art, most notably Derek Jarman’s 1993 film Blue (Tate T14555), which entered Tate’s collection in 2014.81 Indeed, along with Blue, the acquisition of Butt’s work grew Tate’s modest offering of art relating to AIDS. Before the 2010s, very few works were associated explicitly with AIDS in collection texts. These included Jarman’s painting Ataxia – Aids is Fun 1993 (Tate T06768, acquired in 1993), which was included in a photograph by Richard Hamilton from 1996–7 (Tate P78013, purchased by Tate in 1997), Susan Hiller’s From the Freud Museum 1991–6 (Tate T07438, purchased 1998), Leonilson’s The Penelope 1993 (Tate T07768, presented anonymously in 2001) and Martin Kippenberger’s Happy to be Gay (Tate P79162, purchased 2005).

The increasing currency of art by LGBTQIA+ artists and artists of colour was therefore an important context for the acquisition of Butt’s work by Tate in the 2010s. As conceptual installations, however, Transmission and Familiars stand out from the bulk of such artists. Indeed, there is little in these works that might encourage queer readings from gallery-goers. By way of conclusion, I want to consider the obliqueness of Butt’s work in terms of an aesthetics of ‘opacity’, which may be another reason for the institutional ‘rediscovery’ of Butt’s work now. This gives way to a discussion of ‘opacity’ in an expanded sense, one that considers the opacity of institutions and its ramifications for the present and future research.

From an ‘aesthetics of opacity’ to institutional opacity

As Butt’s undergraduate dissertation suggests, the obliqueness of his works is intentional, a form of what the artist describes as ‘strategic withdrawal’.82 This has been discussed by the performance scholar Dominic Johnson in relation to notions of opacity.83 In recent years, ‘opacity’ – not unlike ‘hybridity’ and ‘exile’ in the 1990s – has become a prevalent concept in discussions of contemporary art. As an idea, it is closely associated with the Caribbean theorist Édouard Glissant, for whom the basis for ‘understanding’ and ‘accepting difference’ in ‘Western thought’ is a certain kind of ‘transparency’ demanded of those belonging to minoritised groups.84 Minoritised others must be ‘reduced’, all aspects of their identity rendered legible and knowable in terms of a singular ‘Humanity’, which is coded as ideally Christian, Western and white. In such a paradigm, racially minoritised subjects may be granted a degree of Humanity, but it is of a lower order to that of their white counterparts.85 As a foil to the demand for transparency made of minoritised subjects, ‘the right to opacity’, as Glissant conceives of it, is the right not to be ‘grasped’, ‘enclosed’ and folded into a narrow ‘Humanity’.86 Recently the term ‘opacity’ has been taken up by artists and art historians describing minoritarian aesthetic strategies working against a reductive politics of visibility and representation, and against regimes of surveillance.87 Meanwhile, art historians have argued for an appreciation of the queerness of abstraction.88

It is possible that the increased currency of ‘opacity’, and the more widespread appreciation for abstraction as minoritarian strategy, have also played a role in the acquisition of Butt’s work by Tate. In 2019 Tate acquired three works of conceptual art that may be read as obliquely indexing queer experiences, histories and life-worlds: Transmission, David Medalla’s Sand Machine Bahag – Hari Trance #1 (Tate T15371), first produced in 1963, and Prem Sahib’s 2017 installation Do you care? We do (Tate T15476). In Medalla’s Sand Machine, a trail of brightly coloured beads, hanging from rotating lengths of bamboo cane, creates endless furrows in a tray of sand. Tate’s collection text states that Medalla described the work in ecological terms as ‘a metaphor for the future, when technology will be able to use solar power to help irrigate the world’s deserts’.89 The text also links the title and the beads implicitly to queerness via LGBTQ identities, noting that ‘bahaghari’ translates as ‘rainbow ... conjuring up ideas of hope and optimism, specifically in its universal symbolism for LGBTQ movements across the world’. Notably, this tells us little about the sculpture itself or what Medalla’s interest in the environment might have to do with queerness. Sahib’s Do you care? We do, consists of lockers taken from a now-closed gay sauna, creating an archive of disappeared social and intimate space. The work does not figuratively represent queer people, as in Gupta’s documentary photographs, for instance, but instead indirectly evokes queer histories, practices and spaces that are explicitly named in Tate’s collection text. Along with Transmission, Familiars stands alongside this smaller selection of work that might be framed as making subtle reference to queer lives and histories.

The opacity of art institutions, however, is of a different order to the kind described by Glissant. It is detectable in the lack of documentation regarding how and why decisions are made, or why certain artworks are prioritised for acquisition over others. One of the central questions of the broader Transforming Collections project asks which works, by which artists, are present and absent from public collections of modern and contemporary British art in the United Kingdom. This question has underpinned my examination of Tate’s acquisition of Familiars and Transmission. But equally important is the question of what is present and absent from institutional databases. During this research, I have rubbed up against institutional opacity time and again. Familiars was presented for acquisition twice over a period of nearly twenty years before it was accepted as a gift in 2014. None of this information is provided in the Tate files that I was able to access. Rather, I gathered it by following rumours and recollections, and examining archival traces in documents donated by Jamal Butt.

Institutional opacity may not be strategic or deliberate, but it does allow institutions of various kinds to elude critique, as philosophers Havi Carel and Ian James Kidd argue.90 Absent or fragmented documentation, however, still holds promise. So often, we think of ‘what is there’ in collections records as our only evidence. But queer, feminist and critical race scholars show us that an overemphasis on ‘evidence’ – or on the easily evidenced – can occlude experiences and histories of marginalisation.91 Gaps and silences in records and archives do not have to be thought of as obstacles. They can also unmoor institutional narratives around artworks and open up room for other stories. Beginning with what is absent offers what the philosopher Sarah Ahmed terms a different ‘orientation’ to research into art collections.92

As Tehmina Goskar has argued, museum databases are in many ways designed to forget rather than remember the complex histories around acquisitions.93 But should museums and researchers always make these histories public? The publication of difficult, drawn-out pre-histories should, where possible, be conducted in consultation with artists and those around them, as in this research. Doing so may pose a challenge to narratives of ‘lost’ artists or artworks being ‘found’ and ‘rediscovered’, and lay bare the institutional biases evident in lag or prioritisation. It also contributes to what Carel and Kidd call ‘epistemic justice’ – opening up knowledge of institutional workings to the publics that institutions serve – and might well direct the course of future decisions regarding acquisition towards something more transparent, self-reflexive, critical and equitable. Only then might artists not need to be rescued from obscurity.

There is, finally, the question of how such histories can or should be brought into the public realm – in what form, when and by whom exactly. Any attempt to do so requires sensitivity to specifics, as well as critical thinking and effort from within the museum rather than without. To echo the introduction to this group of Transforming Collections articles, short-term funded projects like this one cannot bring about enduring change in museum practice. Ultimately, then, the answer to this question will lie with institutions themselves.