Since at least the 1980s, it has been observed anecdotally that public art institutions in the United Kingdom have tended to take a partial view of works produced by Britain’s Black and brown artists, prioritising their socio-political content and contexts and the racial identities of their makers over the aesthetic merits and art historical significance of the artworks.1 The art historian Jean Fisher was among the first to acknowledge this phenomenon in her 1997 essay ‘The Work Between Us’.2 Fisher claimed that work by Black and brown artists had ‘been absorbed into discussions of [social and] cultural context that treat it, and the artist, as a sub-category of social anthropology’, so much so that the work had become ‘ensnared in debates of cultural difference and identity that are noticeably lacking in critical discussion about the work itself’.3 Reflecting on the contribution of postcolonial debates about identity and cultural difference to this outcome, she warned against seeing ‘art production as just one among many decodable semiotic systems readily available for appropriation into the analysis of social anthropology’, which, she argued, brought ‘little understanding of the aesthetic and ethical nature of art practice, [and] of the experiential and material base of the art object’.4 She added that cultural prescriptions set by art institutions in the UK along these lines had forced Black and brown artists ‘into the role of ethnographer or social historian … exacerbating the tension between art’s autonomy and social space’.5

Referring to the same phenomenon but recognising its appearance in art criticism, exemplified in reactions to Chris Ofili’s portrayal of the Virgin Mary as a Black woman, the art historian Kobena Mercer wrote in 2005 of an oscillation between ‘a sort of low-grade celebrationism of multicultural murmuring and a highly charged, explosive and divisive controversy, both of which deflect attention from the work of art itself’.6 Mercer argued that:

this oscillation is indicative not only of the problems of art historical amnesia which cannot relate black British or African American formations into that broader story of twentieth-century art but also of the conceptual chaos and confusion as to what the primary object of attention actually is. Is it the background information about the artist's cultural identity, or the foreground matter of the aesthetic work performed by the object itself?7

Echoing Fisher, he observed further that,

writing about art entails a continuous reflection on the circuit and interrelationship between three very different sorts of things: artists (who tend to be human beings); art worlds (which are contingent sociological structures); and artworks (which are usually physical objects). In the discourse of so-called criticisms surrounding minority formations we tend to see an overemphasis on the first and the second, which overshadows, if not completely obliterates, the third. As a result, the dignity of objecthood is very rarely bestowed on the diaspora’s works of art, on the actual art objects that black British artists have produced.8

Implicit in both Fisher’s and Mercer’s discussions was a plea for art historians, art critics and museum professionals to attend to works by Britain’s Black and brown artists as aesthetic and material objects with art historical importance, and to resist mobilising them solely as illustrations of socio-political moments and issues in ways that are comparable to the use of cultural artefacts in social history museums. While, in many cases, works by Black and brown artists do offer social commentary, to ignore their artistic and aesthetic aspects – that is, the creative methods used in their production, the artistic influences imbued in them, and their style, medium and form – is to tell a partial story that dissociates their work from recognised developments in art’s histories, to which Black and brown artists have, in fact, been central.9

Fisher’s and Mercer’s arguments became the premise for the three-year research project Black Artists and Modernism (BAM, 2015–18), led by the artist Sonia Boyce and on which I was a researcher.10 The project sought to explore and make known how Black British artists have contributed to the development of modernism in the visual arts. Heeding Fisher’s and Mercer’s pleas, we made the art object the starting point in all our investigations. We engaged close reading as a research method, which seeks to uncover an artwork’s formal, symbolic and contextual meanings through sustained observation and critical examination of its elements – such as composition, technique, materiality and visual rhetoric. In this way, direct observation takes priority over pre-existing interpretations or theoretical frameworks. The method, akin to literary close reading, is a fundamental art historical method because of its value in direct visual analysis, but it is also a subject of critical debate given its potential limitations in broader interpretative contexts.11 Throughout the project we combined close reading with first-hand testimonies from selected artists about their influences and concerns, to develop novel, object-centred interpretations of the significances of Black artists’ work within the story of British art and modernism in particular.

The research undertaken as part of BAM focused on developing methods for bestowing the dignity of objecthood on works by Black and brown artists, which might then liberate them from being seen as ethnographers or social historians, as Mercer and Fisher had respectively put it. As part of this, we examined how the phenomenon was enacted in display and exhibition object labels and wall texts in art museums, but our efforts were focused on developing new interpretations for artworks, rather than on evidencing absences and hierarchies in museum interpretations.12 Thus, when devising the later, related project, Transforming Collections: Reimagining Art, Identity and Nation (2021–4), one of our objectives was to build an evidence base to document the absence of object-centred discussion in descriptive and interpretative texts produced by art museums for works by Black and brown artists and analyse how this contributes to the art historical blind spot that Fisher and Mercer had observed.

As susan pui san lok summarises in her introduction to this grouping of articles in Tate Papers, Transforming Collections was one of five research projects funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Towards a National Collection programme.13 The programme sought to explore the challenges of developing a single digitised national collections database, comprising information about all the objects held by public museums and galleries in the UK. Transforming Collections focused on the problem that collections information – information museums and galleries hold about the objects in their care – is often scant, absent, incorrect and steeped in imperial logics. Efforts to develop a single digitised collection could not be successful if this issue was not addressed. We therefore sought to surface examples of some of the absences and misinterpretations in collections information that may have been informed by racial and imperial biases.14

Tate was the lead partner on the project and became both subject and object in the research, meaning that its staff were involved in conducting the research, and that it made available a wealth of information about its collection for the project. This included object provenance and acquisition histories and cataloguing, interpretation and display histories, as well as access to its staff who provided detailed insights into policy and practice within the institution. The partnership presented an opportunity to explore the issues at hand with specific reference to Tate as the institution holding the national collection of British art from 1500 to the present day, and arguably, therefore, a key arbiter of what constitutes ‘British art’. Using Tate’s collection information, I sought to evidence the importance of object-focused and art historical discourse in the interpretation of works by Black and brown artists and respond to some of the key questions posed within the Transforming Collections project: whose voices are centred and privileged in collections; how might we surface systemic absences and biases; and how might we resurface an abundance of overlooked artistic creativity?15

Constructing case studies

Sonia Boyce

Missionary Position II 1985

Watercolour, pastel and crayon on paper

Support: 1238 × 1830 mm, frame: 1290 × 1878 × 70 mm

Tate T05020

In my research for Transforming Collections I selected three works in Tate’s collection, made by three contemporaneous Black artists whose work I am a scholar of and whom I had interviewed as part of the BAM project. I had therefore already obtained detailed artist testimony about the respective artworks held in Tate’s collection. The works were Missionary Position II 1985 (Tate T05020), by Sonia Boyce; Go West Young Man 1987 (Tate T12575) by Keith Piper; and The Sky at Night 1985 (Tate T15971) by Tam Joseph. Boyce has been active since the early 1980s, became a Royal Academician in 2016 and represented Great Britain at the 2022 Venice Biennale. Piper has been active since the late 1970s. In 2022 he accepted a commission from Tate to respond to Rex Whistler’s 1927 mural The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats, which spans the walls of what was formerly the gallery restaurant. Although Joseph has been active since the late 1960s and is therefore of an earlier generation to Boyce and Piper, he is often associated with the British Black Arts Movement of the 1980s. For each of these artworks, I took a deep dive into their acquisition, cataloguing and interpretation histories, looking closely at archived correspondence, institutional records and collections information, including internal and public-facing descriptive and interpretative texts that have been intermittently produced by Tate since the 1980s.

Keith Piper

Go West Young Man 1987

14 photographs, gelatin silver print on paper mounted onto board

14 parts, each: 840 x 560 mm

Tate T12575

The first of these texts are catalogue entries, which are public-facing records of artworks that include basic information (for example, when the artwork was made, its materials and dimensions), a bibliography, the exhibition history of the artwork up to the point of writing, a narrative account of the context, origins, history and making of the artwork, and in some cases, an interpretation of the artwork and quotations from the artist. Catalogue entries vary in scope, detail and length according to changes in standards within Tate over time. Often, long or extensive entries are written when an artist’s work enters the collection, the catalogue entry being the site in which information about the artwork is recorded for the first time. Archival records suggest that in 1987, when the first of the three artworks discussed in this essay was acquired, curators were responsible for producing catalogue entries. These were printed and published biennially in Illustrated Catalogues of Acquisitions until around 2000, when the gallery’s catalogue was digitised and published online. Online catalogue entries had a broader audience than their printed predecessors, becoming shorter and more accessible to non-academic audiences over time. From around 2000, catalogue entries were replaced by public-facing ‘collection texts’, known as ‘summary texts’ until 2024, which are based on ‘board notes’.

Tam Joseph

The Sky at Night 1985

Acrylic paint on canvas

1308 × 2317 × 18 mm

Tate T15971

Board notes (occasionally referred to as ‘Trustees notes’) are internal documents written by Tate’s curators and presented to its Board of Trustees when an artwork is being proposed for acquisition into the gallery’s collection. The purpose of a board note is to give an account of the proposed artwork and justify its acquisition.16 Following a work’s acquisition, board notes are converted into public-facing collection texts on Tate’s website. Collection texts offer short, synoptic accounts of the meaning and making of an artwork. Comprising between 500 and 800 words, they offer more than the shorter display labels found on the walls of collection displays and temporary exhibitions, which are typically under 100 words. Collection texts begin with a description of the artwork followed by an account of its materials, how and where it was made, what it conveys and a broader consideration of the socio-political and art historical contexts that informed its production. This is often supplemented by published interpretations of the work by the artist, critics and art historians. Collection texts are based on board notes, and are typically researched and authored by Tate curators, but there have also been several funded projects to commission collection texts by external writers.17 In such cases, fees were modest and required writers to complete texts within short timeframes, meaning that authors could not justify conducting original research such as artist interviews. Instead, writers were encouraged to draw on published scholarship and existing interpretations, potentially perpetuating interpretive biases that might already be at play.18

This article presents three case studies, each offering a short history and analysis of Tate’s acquisition and interpretation of selected artworks by Boyce, Piper and Joseph. Together, the case studies demonstrate how changes in cataloguing practices and inconsistent application of cataloguing conventions at Tate have impacted the critical and historical framing of the three artworks. Together with additional discussion interrogating the benefits and drawbacks of using artist interviews and adopting an object-centred and artist-directed ethos, I reveal what is afforded when Tate engages these approaches in its production of collection information, and moreover, what is forfeited when it does not.

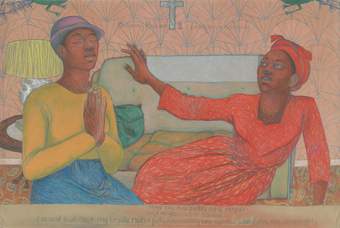

Sonia Boyce, Missionary Position II 1985

Fig.1

Sonia Boyce

Missionary Position II 1985

Watercolour, pastel and crayon on paper

Support: 1238 × 1830 mm, frame: 1290 × 1878 × 70 mm

Tate T05020

The watercolour, pastel and crayon drawing Missionary Position II 1985 by Sonia Boyce (fig.1) was purchased by Tate in 1987, during the early period of the artist’s career. The double self-portrait, drawn within two years of Boyce completing her fine art degree, depicts two figures seated side by side in a domestic setting. Its combination of images and handwritten creolised text, and its references to the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Arts and Crafts movement, are an expression of Boyce’s struggle against the high-modernist dictates of her art school education. The composition is a direct reference to a work by the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas 1939 (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City), and the text and iconography present a meditation on the entanglement of politics and religion.19

After their display in a series of small, one-person exhibitions in the early to mid-1980s, Boyce’s Missionary Position II and several other of her large-scale drawings were in relatively high demand by the nation’s public collecting institutions.20 In September 1986 the Tate Gallery curator David Jenkins visited the large group exhibition From Two Worlds at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, which was devised in relation to the postcolonial theme of ‘cultural plurality’ and sought to exemplify the ‘fusion of European and non-European visions’ in the selected artworks.21 Presumably tasked with determining whether Tate should consider acquiring any of the artworks from the show, Jenkins subsequently wrote to Richard Morphet, Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery, stating:

[While] I do not recommend any action at the moment … The artists I particularly liked were Sonia Boyce, Lubaina Himid and Tam Joseph … The work is of excellent quality … There is no ‘ethnic style’ … the work is sufficiently good to be accepted on its own merits … the Tate Gallery will no doubt be increasingly pressurised to collect work specifically by black artists … the topicality of their subjects gives … these artists an edge which is valuable … the exhibits are metropolitan, post-modern, art school, new art-ish.22

Despite Jenkins’s hesitance to make purchases in haste, within five months a new sense of urgency had developed in relation to obtaining a Boyce work for the collection. Jeremy Lewison, then Assistant Keeper at Tate, wrote to the museum’s Director, Alan Bowness, to suggest reserving three of Boyce’s artworks for consideration, including Missionary Position II, which he described as ‘a colourful work’.23 Bowness authorised the purchase within three days, but the acquisition could not be instigated for another seven months because the artwork was on tour in Boyce’s self-titled touring solo exhibition, organised by Air Gallery in London.24 When the exhibition tour ended, Lewison wrote to Morphet, outlining the cost of two works still available for purchase, Missionary Position II and From Tarzan to Rambo: English Born ‘Native’ Considers her Relationship to the Constructed/Self Image and her Roots in Reconstruction 1987 (Tate T05021). He stated that:

both works are very powerful images … [Missionary Position II] derives its power from its primitivism, its strong colour and bold drawing and from its religious/political message. It is more immediately appealing of the two works in its deliberate naivety and directness … Both works are equally compelling and I recommend that we purchase them both … I think we should act now.25

It is interesting to note that Lewison characterised Boyce’s drawing as ‘primitivist’ and ‘naïve’ in style – terms imbued with racist, colonial and imperial biases. Thankfully such language does not appear in Tate’s recorded descriptions or interpretations of the artwork. This is perhaps because Boyce did not describe her work as such in a later interview with Tate Gallery staff. Such interviews were part of the institution’s commitment, at the time, to an artist-directed approach to cataloguing, which I discuss below.

The purchase and acquisition of both Missionary Position II and From Tarzan to Rambo was completed in the autumn of 1987 and, by the end of the year, Morphet was collating resources to inform research on the new acquisition that would then feed into the production of their catalogue entries.26 These evidently took several years to develop: three years later, in October 1990, Sean Rainbird, Assistant Keeper of the gallery’s Modern Collection, wrote to Boyce stating that he was preparing the entries for Tate’s 1986–8 Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, and asked her to respond to a series of questions about the 1987 acquisition. Demonstrating an embedded, artist-directed approach to cataloguing policy and practice, he explained: ‘We always try to talk direct with artists about their works in the collection in order that the catalogue entries are accurate and have their approval’.27

Presumably Boyce did not respond to Rainbird because just over a year later, in 1991, Virginia Button, another Assistant Keeper of the gallery’s Modern Collection, wrote to Boyce asking the same questions.28 Soon after, Button conducted an interview with the artist. The transcript provided the basis for Button’s catalogue entry for Missionary Position II, which she shared with Boyce in draft form.29 Underscoring the artist-directed ethos expressed by Rainbird, she stated: ‘I’m very keen for you to read the drafts so that any misinterpretation on my part can be moved out’.30 Implicit in Button’s request was the notion that, while there may be value in differing readings of an artwork, it is the artist who is arbiter of interpretations of their own work. I return to this notion below.

Following no immediate response from Boyce, Button wrote again one month later asking her to review and approve the draft catalogue entries, and then again another twenty months later, urging, ‘very little has been written about these works and public interest suggests that there is an increasing demand for information about them’.31 At some point during the course of spring 1994, Boyce must have responded because in June Button wrote to Boyce confirming that the approved catalogue entry had been sent for editing by a colleague. By August that year the catalogue entry had been converted into Tate’s house style, which presumably meant that the text had been formatted for printing.32 It was at least another eighteen months before catalogue entries for works acquired between 1986 and 1988 were published in Tate’s 1996 Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions. It is this same entry that appears on the artwork page for Missionary Position II on Tate’s website.33

At just over 4,800 words in length, the catalogue entry is a substantial and well-researched source of knowledge about Missionary Position II.34 By comparing it with the transcript of Button’s 1991 interview with Boyce, it is clear that the entry is a faithful account of Boyce’s object-centred reflections about the piece: the text includes a close reading of the artwork, discussion of its content, attention to its composition, form and style, commentary on iconographic elements and observation of the artistic strategies taken in its production and in the depiction or articulation of its topics. The textfeatures both direct quotes and paraphrased segments from the interview, evidencing the institution’s commitment at the time to an artist-directed approach to cataloguing.

Object-centred analysis has been a formalised approach within the discipline of art history since the early twentieth century and would likely have been a standard component in Tate’s catalogue entries at the time.35 However, as Fisher and Mercer observed, by the 1990s, when the catalogue entry for Boyce’s Missionary Position II was produced, there was a tendency in discourses surrounding the work of Black and brown artists to focus on racialised identity politics and socio-political contexts over the art object itself. Indeed, in Button’s interview with Boyce, rather than starting with an object-centred discussion of Missionary Position II, she opened with: ‘Many critics have discussed this picture in terms of your personal experience as a woman and as a black woman in a white dominated society but I would really like to hear from your own mouth if that was your intention’. This caused Boyce to respond with:

this term ‘representing a black woman in a white dominated society’ I have had enormous problems with … most of the things that have been written about my work and many other black artists’ work have used this blanket term, in saying that it explains something, but it doesn’t explain anything. You know, I’ve never really set out to work in that way, in that kind of blanket way … If I go back to the works I was doing in 1983 when I’d just left college, what I was trying to do was to make images that I hadn’t been able to see anywhere else … it wasn’t an attempt to talk about black people in a white dominated society.36

Tate’s artist-directed approach to producing catalogue entries was crucial in both allowing Boyce to respond to and refute reductive framings of her work and in enabling her to redirect the discussion towards the art object itself. Thanks to Button’s opening question, the interview started with a lengthy discussion of socio-political contexts for the artwork and of the iconographic elements that relate to those contexts. Following this, Boyce drew Button’s attention to the tension between three-dimensional and flat space in the image, evidencing her own long-held insistence on object-centred analyses. She referenced the Indian drawings and paintings that had inspired the patterns in the artwork, her interest in relief wallpaper, and the work of other artists that had inspired the drawing, including Margaret Harrison, the Mary Cassatt and Frida Kahlo, who were subsequently discussed at relative length in the catalogue entry.37

Had the interview not taken place, and had Button not recognised the importance of Boyce’s own interpretation, the catalogue entry may have overlooked the art historical reference points and significances of Boyce’s drawing, and been premised instead on existing, reductive socio-political assessments of her work. The combination of the artist-directed ethos in place at Tate at the time and the object-centred analysis that Boyce emphasised in the interview produced an interpretation that reflected equally on the work’s aesthetic qualities and its socio-political content and contexts.

The catalogue entry offers several additional ways of understanding Missionary Position II. It highlights themes within the artwork that appear elsewhere within Boyce’s oeuvre at the time, such as religion and relationships of power; it identifies the broader socio-political contexts and issues to which it was responding, such as the role of Christianity within the British imperial project and the proliferation of Rastafarianism across the African diaspora; and it acknowledges other interpretations of the artwork – for example, those that regard it as entirely autobiographical. It is clear from the 1991 interview transcript that Button was driving these additional lines of inquiry and, thanks to the respectful and dialogic approach of the interview, the conversation resulted in an expansive, wide-ranging and nuanced reading of the work that remains in place today.

However, what is presented in the catalogue is markedly different from the information provided in Tate’s current display label text for the drawing (at the time of writing), which was initially written in 2022 to accompany the drawing’s display within the Tate Britain exhibition Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art, 1950s – Now (2021–2):38

Missionary Position II draws inspiration from the intersection of different cultures. Boyce uses herself as the model for both figures, reflecting her growing antipathy towards her Christian upbringing. The praying figure suggests passive acceptance while the figure on the right proposes an alternative position. The head-wrap, adopted in Britain and the Caribbean in the 1970s, is inspired by Rastafari and reflects a growing sense of cultural freedom and connectedness across the African diaspora. By contrast, the ‘missionary position’ title stands as a metaphor for the role of Christian missionaries in imposing colonial rule and oppression.

Comprising 95 words, the text is divided into five sentences. The first characterises the artwork in relation to the theme of cultural hybridity. In the second, the composition and artistic strategy is briefly acknowledged, followed by a summary of the overarching theme or issue at stake within the artwork. The third sentence offers interpretation of the figuration, while the fourth attends to an iconographic element and its representation of the socio-political content and context for the work (the head-wrap as a signifier of Rastafarianism). Finally, the fifth addresses the references and allusions that are at work within the drawing’s title (the role of missionary work within British colonialism). As such, the label skilfully attends to the themes, composition, figuration, iconography and the wider socio-political aspects of the work, all while adhering to a strictly limited word count. However, there is no suggestion as to how the drawing might be understood and positioned within art’s histories or in relation to contemporary art. This type of commentary is an important part of an introduction to an artwork. During research at Tate as part of my PhD, and again as part of the BAM project between 2015 and 2018, I observed that art historical appraisals were commonplace in gallery labels for works by white, male artists in Tate’s collection.39 Despite the catalogue entry for Missionary Position II being replete with discussion of Boyce’s artistic influences and contexts, a decision was made not to include this in the label.40 In consequence, the work is presented as existing in an art-historical vacuum, which potentially precludes consideration of the artist’s position and significance within art’s histories.

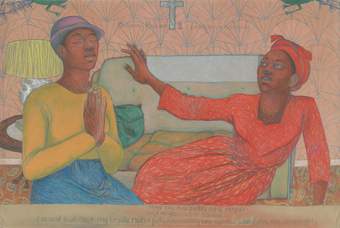

Keith Piper, Go West Young Man 1987

Fig.2

Keith Piper

Go West Young Man 1987

14 photographs, gelatin silver print on paper mounted onto board

14 parts, each: 840 x 560 mm

Tate T12575

Keith Piper’s Go West Young Man 1987 (fig.2) is a series of fourteen narrative panels, combining hand-developed black and white photographs with printed and handwritten text, mounted on boards.41 It is the third of several iterations, the first having been produced in 1979 and the second in 1982. The artwork is a key example of the many highly referential, sequential artworks within Piper’s oeuvre that visualise Black history and ongoing political struggle by engaging collage, copy art and punk-inspired poster art.42

In 2008 Tate purchased the 1987 iteration of Go West Young Man. The acquisition was first proposed by Tate’s then Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary British Art, Andrew Wilson, to Tate’s Acquisitions Monitoring Group in June 2007. There are no records indicating what prompted the proposal, but Wilson wrote to Piper in the same month to confirm that Tate wished to reserve the artwork. There followed a brief exchange of correspondence between the two, discussing the price of the artwork, leading to its acquisition the following year. The letters do not reveal details about Tate’s interest and objective in acquiring the work, nor about Piper’s desires and specifications for its display and interpretation. However, the board note for the proposed acquisition, written for Tate’s November 2007 board meeting, offers insights into the impetus for its selection as well as the critical and historical framings that Tate staff were intending to engage in its display.

The board note offers a description of the artwork, using the keywords ‘slavery’, ‘colonial history’ and ‘black identity’ in the first sentence to assert its overarching themes.43 It also notes Piper’s chosen media, including Letraset, ‘complex printing processes’, grid-based forms and a combination of text and found images. The description does not, however, reference the histories of art with which Piper was engaged when making the work, such as collage, punk-inspired poster art, pop, protest and copy art, and both modernist and conceptualist art more generally.44

The board note then presents the rationale for acquisition, which was to aid in increasing the ‘representation of black artists’ in the collection.45 When addressing racialised underrepresentation within public art collections, however, it is crucial to consider how approaches to interpretation may contribute to the subsequent minoritisation or peripheralisation of those artists within a white-majority collection. Including in the board note non-racialised artistic contexts in which the work might additionally be understood could extend the range of future display contexts for the work beyond those of ‘race’ and racism, potentially allowing it to appear more frequently within Tate’s programme. In this note, the opposite effect was achieved through its specific framing of Piper’s work in relation to works by other artists of colour in the collection (Rasheed Araeen, Donald Rodney, Black Audio Film Collective). This elides important differences between artists, especially in terms of their artistic approaches and chosen media, while also encouraging the perception that their work should primarily be interpreted through a prism of ‘race’. Through this limited lens, Piper’s Go West Young Man may be read as significant within Tate’s collection only in terms of his racial background and his concern with Black history and ‘the Black experience’.

In 2013, five years after Piper’s work was acquired, the art historian Fiona Anderson was commissioned by Tate to write a summary text for the artwork based on the board note and existing scholarship on the artwork.46 Anderson’s text observed the artwork’s materials and composition, the artistic strategies at work in it and the artistic context in which it was made (primarily in association with the Blk Art Group). The text also included Piper’s own interpretation of the artwork, through direct quotations from catalogue essays and academic texts authored by the artist. In this way, Anderson was able to incorporate Piper’s voice and intent in the text, echoing the artist-directed ethos taken in the production of the catalogue entry for Boyce’s Missionary Position II.

Among the quotations was the tantalising assertion from Piper that, in making the artwork, he had been concerned with ‘researching and re-evaluating notions of creative practice which have been formerly marginalised and obscured, and fusing them with the prevailing currents of contemporary practice’.47 Anderson did not unpack what this approach entailed, perhaps because doing so would have entailed further research, possibly involving an interview with the artist, which would have been beyond the scope of her fee and brief (to provide a synoptic account of the work for a general audience within a tight word limit). Herein lies one of the difficulties resulting from the changes in Tate’s cataloguing practices and conventions. In the 1980s and 1990s, before artwork records were published online, Tate staff conducted extensive original research involving artist interviews if required, resulting in longer catalogue entries that could be broad in scope and offer nuanced, insightful interpretations of artworks informed by the assertions of their makers. But after artwork records began to be published online in around 2000, their length and scope was reduced. And when external writers were commissioned to produce collection texts, as was the case for Go West Young Man, the fee could not justify extensive research or artist interviews. This means that such writers depend on information provided in board notes and on existing scholarship. If these sources are in any way skewed, ill-informed or lacking, this is likely to be repeated in collection texts.

Anderson’s text, for instance, echoes the themes and iconographic elements prioritised in the board note (‘slavery’, ‘colonial history’ and ‘black identity’) and similarly overlooks Piper’s artistic concerns. Had there been scope to extend the length of the text, and time and funds to conduct original research, including an artist interview, it may have been possible to present a broader and more nuanced range of insights about Go West Young Man, including its art historical references and significances.

The limitations of the 2007 board note and the subsequent 2013 summary text were replicated in the content of a display caption for Go West Young Man produced in 2017, which remains online at the time of writing:

In Go West Young Man Piper combines text with images relating to the slave trade and the abolitionist movement in Britain, stills from Hollywood films, family snapshots, photographs of lynching and black male bodybuilders. He uses these to explore the historical, social and cultural depiction of the black male body. In each panel, the brutality of the ‘Middle Passage’, of slavery (the crossing of millions of African slaves across the Atlantic from Africa to the ‘New World’ colonies in slave ships from the 15th to the 18th centuries) is related to Piper’s experiences of racism, violence and the justice system.

The caption lists the materials, subject matter and themes of the work and outlines the socio-political issues Piper was concerned with in its making. Crucially, it does not offer any form of aesthetic, critical or art historical commentary about the artwork. Would the artwork’s significance in the wider histories of art have come to the fore in any of Tate’s interpretative texts if Tate had interviewed Piper about it as part of an artist-directed approach to producing collections information?

Tam Joseph, The Sky at Night 1985

Fig.3

Tam Joseph

The Sky at Night 1985

Acrylic paint on canvas

1308 × 2317 × 18 mm

Tate T15971

Tam Joseph’s The Sky at Night 1985 (fig.3) is a large-scale acrylic painting on canvas depicting an urban housing complex. It is one of several paintings and drawings by Joseph featuring the night sky and representing lived experiences of Britain’s Black population. As with many of his works from this period, The Sky at Night is painted using thick, gestural brushstrokes, evoking Joseph’s admiration for the expressionist painters of the early to mid-twentieth century.48

Tate acquired Joseph’s painting in 2022. Prior to the acquisition, it was included the exhibition Life Between Islands. During the course of the show, Joseph was listed in Tate’s collection strategy for 2021–6 as being ‘among artists born under the British Empire who made a key contribution to post-war British art but are not represented in the collection’.49 This was echoed in the rationale for the acquisition of The Sky at Night in a board note produced in April 2022. In my wider research into the acquisition and interpretation history of Joseph’s work across UK public collections, which I conducted for the Transforming Collections project and presented at the project’s 2024 conference at Tate Modern, I found that his work has been discussed in catalogue entries, display labels and exhibition catalogue essays almost entirely in terms of its socio-political content and contexts, rather than in terms of its relationship with and contribution to the canon of British art.50 With the issue of racialised underrepresentation at the heart of Tate’s rationale for acquiring The Sky at Night, one might expect the museum’s interpretation to follow the approach taken by other UK collections. In these examples, the socio-political content and context of the work provides the focus, and artistic and aesthetic concerns are either secondary or absent.51 However, the ‘About the work’ section of the board note, authored by the Tate curators Bilal Akkouche and Elena Crippa, offered a balanced and nuanced reading of the artwork that took account of its content and context as well as Joseph’s artistic influences and approach to painting.

The board note was edited into a collection text for The Sky at Night and published online in 2024.52 Like the board note, the collection text includes numerous citations, evidencing the extent of the research underpinning it. The text offers a detailed description of the artwork, acknowledgement of the influence of the French expressionist Chaïm Soutine on Joseph’s painting style, recognition of the references in the artwork to the figuration of the British painter L.S. Lowry, and of Joseph’s concern with urban planning and social housing. It combines artist testimony, including quotations from the artist and citing correspondence between the curators and the artist, and interpretation by the artist and art historian Eddie Chambers and others.53 The scholarly, object-centred and artist-directed approach taken in the production of the board note has resulted in a well-rounded interpretation of The Sky at Night, which has the potential to open out new art historical contexts for displaying Joseph’s work, as well as for further research and analysis.

Evaluating Artist Interviews as a Method for Producing Collections Information

The case studies presented in this paper offer a detailed account of the acquisition, cataloguing and interpretation histories of three works by Black artists in Tate’s collection. My approach has been informed by Jean Fisher’s and Kobena Mercer’s shared observation that object-centred art historical analysis has been absent in discourses surrounding the work of Britain’s Black and brown artists as developed in art criticism, art scholarship and by museums. It has also responded to the objectives of Transforming Collections: to surface the biases, absences and erasures that may be present in collections information for works by racialised and minoritised artists.

Since the case studies represent a small sample, the collection information analysed therein is not necessarily representative of that produced for all works by Black and brown artists in Tate’s collection. However, the case studies are key indicators of how changes and inconsistencies in Tate’s cataloguing conventions between the late 1980s and the mid 2020s have impacted the degree of presence and absence of object-centred, aesthetic and art historical analysis in the collections information produced for the selected artworks. In the case of Boyce’s drawing Missionary Position II, this kind of analysis appeared throughout the lengthy 1994 catalogue entry but then disappeared in the significantly shorter 2022 display caption. But with Piper’s Go West Young Man, such analysis has yet to feature significantly in any of the internal or public-facing artwork information produced by Tate. The Boyce and Piper case studies therefore support Fisher’s and Mercer’s claims, with the Boyce example demonstrating that even when this kind of analysis is included in catalogue entries, it does not necessarily feature in subsequent display captions, which are the main form of collections information that audiences encounter (hence Fisher’s and Mercer’s observation). However, in the case of Joseph’s recently acquired painting The Sky at Night, object-centred, aesthetic and art historical analysis has appeared in all the collections information produced for the artwork to date (the board note and collection text).54 What seems to unite the instances in which this kind of analysis features in the collections information produced for the Boyce and Joseph artworks is an artist-directed approach, and specifically, the use of artist testimony in correspondence and interviews.

Within my own practice as an art historian, I have found asking Black and brown British artists directly about their approaches, influences and objectives (and when this is not possible, drawing on comparable sources, such as published interviews and artist statements) to be a simple but effective method for counteracting existing, partial interpretations of their work. Hearing from artists, first-hand, about what and/or who informed the making of their work as part of an object-centred interview enables me to consider the aesthetic and art historical significance of their work alongside its socio-political content and contexts. But interviews with artists are not without limitations.

Artist interviews are generally conducted to document their voices and testimonies, often with the objective of uncovering the purportedly real or hidden meaning behind an artwork or revealing the artist’s personality.55 In such instances, the interview serves as a means of uncovering that meaning from the artist’s perspective.56 Alternatively, some approaches prioritise the retrieval of information, focusing on gathering factual details.57 Underlying all these objectives is the concept of ‘authenticity’ and the positivist assumption that the acquisition of information facilitates the revelation of truth. This conceptualisation of the artist interview has been subject to critique from multiple perspectives. Scholars have highlighted several challenges that complicate the notion of accurately capturing an artist’s intention. These include the fluid and evolving nature of an artist’s ideas over time, the inherent difficulty of translating complex thoughts, emotions and mental imagery into language, and the influence of situational context on an artist’s statements. Additionally, artists may fabricate or reconstruct their accounts when unable to recall their original thought processes, further complicating the assumption that interviews can yield a definitive understanding of artistic intent.58 The notion of the ‘death of the author’, as articulated by the philosophers Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida in the 1960s, challenges the practice of attributing meaning to a text based on the author’s biography and intentions.59 Instead, their arguments emphasise the role of the reader in constructing meaning, thereby shifting the interpretative focus away from authorial intent. From this perspective, it becomes necessary to critically evaluate the extent to which the artist’s voice should be privileged over other sources of information and interpretative frameworks in the analysis of artistic meaning.60

Numerous scholars have highlighted the performative dimensions of artist interviews, emphasising how artists may present a constructed version of themselves that differs from their private identity, complicating the notion of ‘authenticity’.61 In this context, some artists – particularly those experienced in interviews – may provide rehearsed or formulaic responses, lending the exchange a scripted quality.62 Likewise, interviewers often rely on established conventions, adhering to standardised formats and predetermined question structures, which can further constrain the dialogic nature of the interview process.63 The interview is shaped by the intentions, biases and framing strategies of the interviewer, whose questions guide or limit the interviewee’s responses.64 Moreover, interviewers may introduce interpretations that had not previously occurred to the interviewee, but which they may accept in the moment. Given these complexities, the extent to which an interview can be regarded as truly ‘authentic’ or as a reliable form of evidence remains a critical point of inquiry.65

The broader context in which an interview takes place also significantly shapes its dynamics and outcomes. Factors such as the act of recording, the intended purpose and potential publication of the interview, the agendas and relationship between both parties, and the presence of formal consent procedures can all influence the discourse.66 These contextual elements often remain unacknowledged. However, increasing scholarly awareness of these influences has led to the recognition of the interview as a ‘mediated dialogue’.67 The editing process further reinforces this mediation, as interviewers, editors and artists actively shape the final text. Artists may revise or rewrite entire passages of transcribed speech, while interviewers and editors can function as ‘gatekeepers’, selectively omitting material deemed superfluous or irrelevant.68 Rather than viewing the contextualised and constructed nature of the artist interview with scepticism, several scholars interpret it as a co-created, dialogic exchange that challenges the notion of singular authorship.69 In this view, the interview serves not only as a method of documentation but as a form of critical inquiry, actively producing discourse around an artist or artwork.70 This conceptualisation positions the interview as a disruptive methodology within both artistic practice and art historical scholarship. For instance, during the 1960s and 1970s, numerous artists’ magazines incorporated interviews as a means of opposing the formalist reading of art popularised by the critic Clement Greenberg, which sought to exclude artists from the interpretation of their work.71 Through the interview format, artists were able to reassert their presence, engage in self-representation and either challenge prevailing art criticism or reclaim it as a tool of their own making.72

Embedding an artist-directed ethos

In developing my own interview methodology for the earlier BAM project, I remained observant of Fisher’s call to ‘attend to the work between us’, adopting an object-centred approach that prioritises the formal and material qualities of artworks. This approach considers how the artistic influences and strategies embedded within an artwork contribute to historically and critically situating the artist’s practice. This methodology allows the artist to guide the development of my interpretations. While this is not an uncommon practice, my approach aligns closely with that of the art historian Ella S. Mills, who draws inspiration from Hazel V. Carby’s influential 1982 essay, ‘White Woman Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood’.73 Mills advocates for a shift away from merely reporting on artists’ statements towards a mode of engagement rooted in active listening.74 To achieve this, she employs Grounded Theory, a methodology that acknowledges the researcher’s subjectivity and recognises the constructed nature of the interview process. This framework underscores that an artist’s articulation of their reality is shaped by their own lived experiences and cannot be assumed to represent a universal truth. By integrating these principles, Mills argues that art historians can reconceptualise the interview – not as a tool for uncovering objective truths, but as a means of consciously co-constructing knowledge through dialogic exchange.

Virginia Button’s interview with Sonia Boyce in 1991 could certainly be viewed in this way, and its benefits for the production of collections information is evident. The interview, conducted as part of Tate’s artist-directed ethos, combined with Boyce’s object-centred responses, provided a powerful counterbalance to the partiality of collections information that was, according to Fisher and Mercer, becoming widespread in the interpretation of works by Black and brown artists in the 1990s. Although an artist-directed approach does not seem to have been applied in the production of collections information for Piper’s Go West Young Man in 2008, it does appear to have been prioritised in information created as part of the acquisition of Joseph’s The Sky at Night in 2022. The collection text for Joseph’s painting brings the art object into focus, drawing attention to its form and materiality, its aesthetic quality and the approach taken in its production. This informs comparisons with the expressionist painters that Joseph references as sources of inspiration, fostering an understanding of how he might be situated both art historically and as a contemporary artist. Moreover, it advances an appreciation of his work beyond the arguably narrow confines of ‘Black Art’, which, as a racialising category, has served to exclude Black artists from the core narratives of art history.

The research presented in this article, with its limited dataset relating to the acquisition and interpretation of only three examples from Tate’s 70,000-strong collection of artworks, cannot provide conclusions as to the museum’s cataloguing practices. Further comparative case studies examining collections information for other works in the collection, including those by white artists, would help to establish whether the absence of an artist-directed approach in the Piper case study is an anomaly, or indicative of larger-scale inconsistencies in Tate’s cataloguing conventions over time, or according to the racial identities of artists. What these three case studies do reveal, however, is the value of an object-centred and artist-directed ethos within cataloguing and interpretation, and moreover, what is elided when such an ethos is not embedded in practice or is inconsistently applied.