During the modern art conservation training programme, many reconstruction exercises are undertaken for educational and research purposes.1 With the assistance of the artist or a relevant material specialist (for example, a woodworker or blacksmith), to-scale reproductions are made using the same materials and imitating the working techniques employed to create original artworks. Only by actually remaking an artwork can the full extent of the original working processes be understood.

Looking at them now, what are the end results? Could these study-copies serve as ‘exhibition copies’ or remakes? Under what restrictions could they be presented? What are the conditions of a successful copy?

Fig.1

Copy of Barbara Hepworth’s

Orpheus (Maquette 2) 2001

© SRAL Maastricht

Study copies

Training includes copying medieval sculpture and panel painting as well as woodcutting. In the reproduction of a wooden sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, the aim was to learn how she used the chisel but also to produce a finished sculpture, a free copy.2 The end result, with partial white enamel paint, looked beautiful and ‘real’. However, it will never be mistaken for a Hepworth because it is not catalogued and has no pedigree or patina.

A more complex Hepworth 1:1 reproduction was made in 2001 when conservation of Orpheus commenced.3 To fully understand the complex method of stringing, the cut out shape of the metal, the possible tension in the bent metal figure kept together by the strings, and the suspected danger of the shape loosening when strings are lost, a copy was made.

Again, as a student project it was very interesting to learn that what appears to be a simple construction is a well thought-through shape with a mathematically precise process.

The parabolic flat shape was cut from copper plate. Over eighty holes were drilled and the shape was bent with extreme force. Finally, the two strings, almost twenty metres in length, were added. Unfortunately, the patina imitation was not as successful due to the lack of experience. It also proved difficult to get an identical logical cone shape and bending with the same natural look. Indeed, even with the help of a professional blacksmith and exact measurements, the replica did not resemble the original as the artistic balance and the patina were difficult to match.

A metal copy of Donald Judd’s Untitled 1967 was made in galvanised steel with green lacquer by a blacksmith whilst the work was undergoing conservation treatment in 2000.4 Details of strips, welding, bending and the surface of the galvanised steel plate with the typical frosting effect were all copied. The copy was made in reverse so as to avoid it being mistaken for an original Judd. In fact, the results looked so good that the remake was ‘signed’ by hammering the text COPY and RvH 2000 in the back ridge.

The only problem that arose when producing this copy was in obtaining the correct plate material. This is because apparently, owing to new environmental restrictions, there is no longer a lead component in modern-day galvanised plated steel. The ice-frosted surface structure, preferred by Judd, is therefore less prominent in modern plates. This case study shows that an object that was produced by a fabricator as a technical translation of the design of the artist is possible to copy. Indeed, during Judd’s lifetime, works were produced and reproduced to his own very precise instructions.5

Artist copies

Henk Peeters

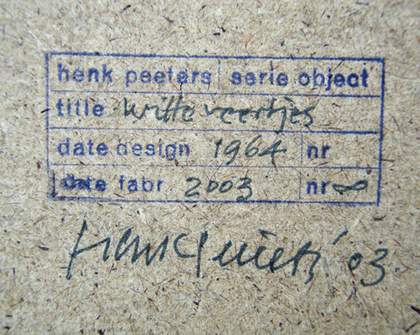

Fig.2

Henk Peeters

White Feathers 2003

© Henk Peeters. DACS 2007. All rights reserved

Fig.3

Henk Peeters

White Feathers 2003

Detail of signature

© Henk Peeters. DACS 2007. All rights reserved

Henk Peeters is a well-known example of an artist who is open to remakes. His Zero and ‘informel’ roots proposed that every person could make his own ‘Henk Peeters’, by following the way he made his Pyrografies (a series of candle-burnt holes in white PVC foil plastic on a stretcher). But asked to make an artist’s remake of 59–18, 1959, he discovered that present-day PUR foam contains fire retardants and it burns ‘not so nice’ as in the old real PUR foam.6 Henk Peeters still sells remakes of his early works in his gallery numbering them as 62–17 1962 remake 2005. The price of such a remake is a modest but ‘real’ art price (even artists need to make a living). The difficulty here is the (absence of) patina which, despite being indefinable, is priceless in the market.

Tom Claassen

Tom Claassen, a young successful sculptor, was interviewed as part of the Artist Interview Project II.7 A typical representative of his generation, Claassen has a website, good entrepreneurial skills, a production line in China for outdoor sculptures and a different artistic structure from an older generation of artists with their studios full of paintings, tubes of paint and stretchers.

His early works are ‘inside-out’ casts of different objects in natural rubber. The Kröller-Müller Museum has the Lavatory Cubicles 1991, displayed as hanging closets on a hook. He has also made ‘carpets’ of spaces such as a part of the stone floor of his studio ‘sandcast’ in rubber. Responding to questions raised by museums about how long the latex rubber carpet would last, he added step-by-step do-it-yourself instructions on how to remake these rugs every ten years when the material is deteriorated. Claassen stated that anyone with some creative skills would be perfectly able to produce a remake after an original.

A dry run of this proposal was set up during the planned artist interview in 2003. The filmed interview took place in the Kröller-Müller museum where some of his major rubber works are held. One of the four rubber owls was missing from the installation Untitled 2000. The plan was to remake it during the interview. Claassen would give the instructions and the conservator would learn how to do it. But during the performance his first doubts arose: Was the tree trunk used the right way up or upside down for the ‘reverse-cast’? Which side would serve best the front and which the back? The turning inside out, over the prepared polystyrene shape in which the owl-sound-producing speaker would be placed, was suddenly not clear, even with the other three owls available. In the interview film, one can see the artist turning from being convinced that the museum could do the remake to struggling with artistic details, i.e. the decisive choices in the making process. In fact, even if the museum remake would have looked alright (at an installation height of four metres in a tree), it definitely would not have been ‘the real thing’. Last year Claassen did indeed remake the missing fourth owl in his studio and it looks rather different than the other three. However, it is an original.

Reconstructive conservation

Numerous examples exist of artworks with reconstructive repairs, replaced lost parts etc. Rebecca Horn’s Das Goldene Bad 1980, is an interesting case where the artist was not the actual producer.8 Horn presents a 180 x 180 x 45 cm ‘bath’ consisting of, on the outside, rusting steel plate, with plated brass (gold) inside. The bath is filled two-thirds full with water. It is then covered with a 180 x 180 cm glass plate in which a poem is engraved, embossed with gold leaf. The current glass plate is already a remake of the original that broke while being transported.

The brass ‘inner bath’ has also leaked and water caught between the brass and steel plates has caused steel corrosion that has distorted the brass plates. As a conservation treatment, the full inner bath was removed and replaced with a new one, completely welded, in keeping with the look of the plates and strips of the original. Currently, the 1cm thick outside bath is, in fact, the only original part that still exists. For the museum, the destructive removal and remaking of the original inner plates was preferred, deemed more original, than a complete remake where the original could be kept in store. The final decision was also down to practical reasons relating to storing the two big heavy pieces and the feeling of one being ‘more original’ than another.

Final considerations

Producing remakes of sculptures that, owing to a material defects, will be lost forever (Naum Gabo) serves the public by providing good copies that keep artists’ work ‘alive’.

Similarly, it seems acceptable to reconstruct works that are lost by traumatic incidents (war, fire). See, for example, the cathedrals after WWII or the old bridge in Mostar, Bosnia Herzogovina.

However, it also feels necessary to produce remakes when the original still exists or when the artist/assistant/family is still around to respond to the end results (László Moholy-Nagy, Marcel Duchamp). The shifting status of originality can be experienced with new plaques by Marcel Broodthaers (unsigned but produced in the same manner as the original) that keep coming on the market.

Why are paintings different? Da Vinci’s Last Supper is almost lost but a replica would not be appropriate or appreciated. The replica of the cave and rock paintings in Altamira, Spain, right next to the original, still smells of GRP-casting.

Who should believe a replica to be the original? Where lies the magic of the original? This is the heart of this discussion, though maybe only in our minds, as to the eye anything can be copied, falsified, replicated and remade. As for representing an artist or an artwork, a 1:1 real material remake works so much better than any photo collage or three-dimensional movie.