Fig.1

Carsten Höller

Test Site 2006

Photo: Tate © Carsten Höller

The desire to blur the boundaries between art and life was shared by a great number of artists working across the world in the 1960s. One of the most radical forms to emerge from this shared concern was a type of art that emphasised the lived experience of its viewers by requiring them to adopt new forms of active participation. These participatory practices, which I have chosen to call ‘do-it-yourself art works’, took the form of environments to be entered by the participant (in Allan Kaprow’s pioneering environments of 1960–3, or Hélio Oiticica’s works from 1967), as well as objects to be worn or handled (in the case of 1960s works by Oiticica and his Brazilian fellow artist Lygia Clark, as well as the group known as Fluxus).

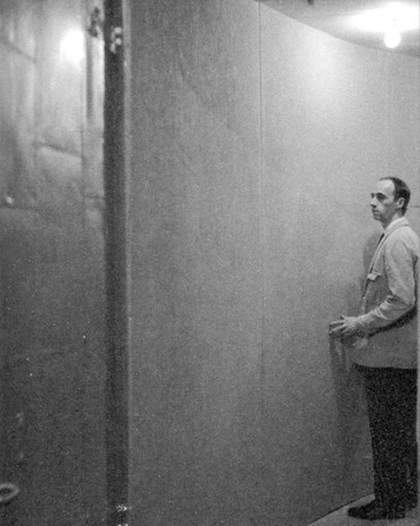

Unlike most art works displayed in museums, do-it-yourself art works cannot exist in themselves. Lygia Clark called her works ‘springboards’ for the viewers’ experiences;1 do-it-yourself art works act as vehicles, tools or stages for the participants’ actions, thoughts and feelings. Direct physical participation in the museum, however, poses major display and conservation problems, as originals created by the artist can be substantially damaged when they are handled by large numbers of visitors. Theoretically, the issue is further complicated by the fact that unlike contemporary participatory works (such as Carsten Höller’s Test Site at Tate Modern in 2007), most 1960s practices were conceived outside, if not in opposition to, the museum. Notions of lived experience, change, movement, and spontaneity, upon which a political discourse of freedom and self-discovery revolved, were considered antithetical to an institution, which, according to Kaprow, ‘reeked of holy death’.2

Fig.2

Carsten Höller

Test Site 2006

Photo: Tate © Carsten Höller

Kaprow himself tackled this problem when he was asked to recreate his early environments for subsequent exhibitions. Explaining that ‘the past can only be created (not recreated)’, he refused to present reconstructions based on sketches and photographs.3 Instead, he created new environments loosely related to the originals, sometimes to the annoyance of the curator.4 (The event organised at Tate Modern on 29 May 2007, in which gallery visitors were invited to make their own Parangolé capes and dance the samba in them around the Turbine Hall, allowed the capes to be brought back to life for the space of an afternoon, but remained independent from the exhibition itself.) Documentation is an entirely inadequate substitute for the actual experience of do-it-yourself art works, which emphasised lived experience in order to counter the passive absorption of images churned out by an increasingly powerful of ‘society of the spectacle’. Even displayed alongside replicas, documentation can play an inhibiting role, as participants often feel compelled to copy what they see in the photographs or films, rather than engage with the objects in themselves.

Like many forms of conceptual art, do-it-yourself art works effected a radical de-emphasis on the art object as a repository of aesthetic and commercial value in itself but, unlike other forms of conceptual art, this dematerialisation operated through a combination of sensory perceptions rather than the withdrawal of sensual pleasure. This ambiguous position means that do-it-yourself art works cannot be apprehended, like other conceptual works, through the mind and imagination alone, and they maintain a presence based on specific formal and material characteristics. Paradoxically perhaps, then, it is because they are still anchored in a material presence that do-it-yourself art works should be replicated. And it is because their formal and material characteristics depend on the choice and arrangement of objects, rather than on the artist’s individual style of painting, that they can relatively easily be reproduced. In this sense, as Jon Hendricks, curator of the major Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, explains, ‘a replica of an interactive work,’ which allows people to ‘have the experience of using it’ and which is clearly labelled as a replica ‘is really not all that different from a photograph’.5

Of course, one could argue that do-it-yourself practices – like most, if not all, avant-garde utopias – failed in their ambition to change the world, and more specifically, to radically challenge the museum. Fluxus certainly never developed an alternative network of production and distribution powerful enough to pose a threat to the art market, and the audience for most do-it-yourself art works often remained limited to small groups among the artists’ friends. In fact, experiments in spectator participation on a larger scale did not always go according to plan. Robert Morris’s 1971 retrospective at Tate, for example, had to be closed down after only a few days because enthusiastic participants injured themselves and destroyed many of the objects in the exhibition. Just as they are required to retrieve the utopian aspirations of de Stijl or the surrealists by looking at their works in the museum, twenty-first-century viewers could thus be invited to contemplate, in a do-it-yourself art work displayed in a glass case, the relics of yet another failed project.

I would like to argue, however, that viewers cannot adequately evaluate the success or failure of do-it-yourself art works unless they are allowed to engage with them in the objects’ own terms. From this perspective, the trashing of Morris’s 1971 show would be considered not so much a failure as a resounding success: participants truly engaged with the work, and demonstrated very concretely what freedom meant for them.6 In fact, I have argued elsewhere that do-it-yourself art works always set up a tacit contract between the artist and the participant, in which the artist gives over some of his or her power on the condition that the participant makes an effort to engage with the work according to some implicit, and sometimes explicit, rules of behaviour. The breakdown of this contract is, of course, always a potential risk arising from the artist’s abdication of some of his or her traditional control. Inhibiting spectator participation obscures this relationship of trust and its attending dangers. Whether one believes that this new relationship allows an actual blurring of art and life, and whether one believes that it could operate in a museum context at all, this feature should remain accessible to all viewers through the use of recreations or replicas.