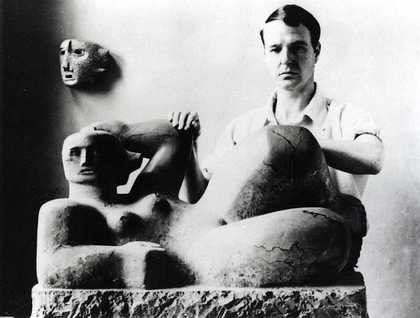

Fig.1

Photography: © Julian Stallabrass

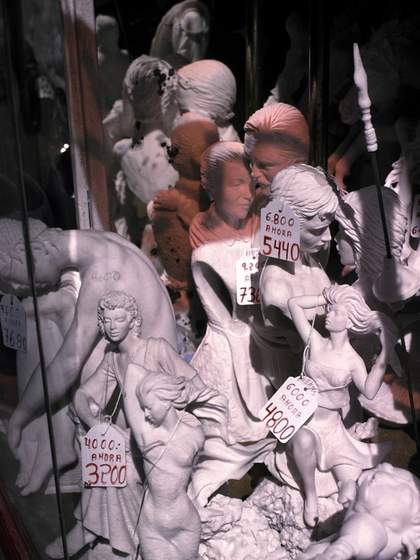

The title suggests, with an air of irony perhaps, but that does not withdraw the implication, that replication in sculpture is an inherent vice (an internal flaw that will damage the value of the piece). Why should this be so? The vast majority of sculpture is replicated, and not merely in the cottage-industry of the artist’s studio but in industrial manufacture. There is, beyond the uncertain remnants of sculpture left in the contemporary art world (objects, installations, environments, interventions, the remains of performance and of ‘relational aesthetic’ events), a vast production and display of what is conventionally but definitely seen as ‘sculpture’ by its users. It includes the signal sculptures of Las Vegas, garden figures (mass-manufactured out of concrete, resin and other substances for sale in garden centres) and figurines for mantelpieces and shelves. The great majority of this is replicated, and no one thinks it should be otherwise. In addition, museums in which the holdings lie outside of copyright, are happy to replicate sculptural objects in unlimited editions to sell in their shops (think of all the replica Egyptian cats in the British Museum).

This ‘virtuous’ replication, which has no effect on the value of this sculpture, allows us to think out the art world’s peculiar relation to reproducibility. The relation of sculpture to the replica has generally been more complex than that of, say, painting. Editioning of cast sculpture has been the norm. Excess or unofficial editions present two separable problems: one is of quality control; the other of contractual and legal violation. The latter may flood the market, devalue previously produced editions and erode the reputation of the artist or estate. But if these two problems are not involved, is there still some residual prejudice against replication?

If we think of Henry Moore’s practice, many casts of the same or very similar pieces were produced at different sizes and in different editions. The artist’s input into the process of enlargement was variable. Even carvings could be produced as replicas of sorts, copied by skilled craftsmen who worked to produce marble versions of Moore’s bronzes. Does even the sanctioning of the artist in the production of these replicas (while it assures them of official status) tend to devalue the work as a whole?

There is a simple economic argument here of supply and demand; it is most unclear that the artificial restriction of production to raise prices – which many artists practice even with non-reproducible works – is the subject of any more vice than profuse production. Rarity is, though, tied to the general value that is attached to art, and that is related to its price: for the unique work, demand may be elastic but the supply is finite and fixed (in this, the art market is most unusual).

So is replication an inherent vice? Only if one thinks that:

- the touch of the artist is central to the work

- that the artist’s supervision is needed in making the work

- that the making of art works is a fundamentally individual pursuit

- that the auratic art work should only be in one place and a particular time

There were, of course, many works made with such precepts in mind, but no one thinks that way any longer, do they? And if not, then the older works must take their place in the context of the new.