In 2002, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art opened Eva Hesse, a comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s works including sculpture, works on paper and paintings.1 The advance planning required for assembling such an ambitious exhibition afforded conservation staff at SFMoMA significant time for the examination of condition issues in the artist’s work, especially sculptural works made from ephemeral materials. In addition, extensive experimentation with natural rubber and other materials used by Hesse was undertaken by the conservators.2 Mock-ups were made to gain a great understanding of the properties of the materials, and techniques were employed to attempt to recreate the effects as seen in her work.

Fig.1

Doug Johns preparing Sans II mock-up

SFMOMA 2002 © The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

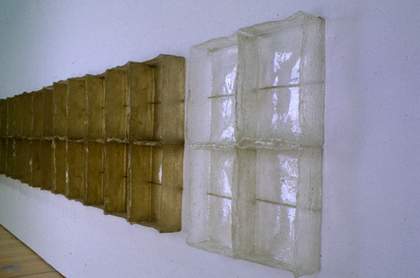

Doug Johns, one of Hesse’s main assistants, was responsible for fabricating most of the artist’s polyester works. Johns now resides in Southern California, which facilitated interviews at his home prior to the exhibition and subsequent visits by Johns to SFMOMA during the course of the exhibition. Michelle Barger, objects conservator, led Johns through the installation and videotaped their discussion of the sculpture. Topics covered included fabrication, condition, limits of variability in disposition, and studio practices with respect to his role in the creation of the work. During another visit to SFMOMA, Johns brought his two original polyurethane moulds used to make Sans II, 1968, a fibreglass and polyester work comprising five sections. Each section is made up of twelve boxes, six boxes from one mould across the top, and six from the second mould across the bottom. SFMOMA owns one of the five sections and Barger requested that Johns bring the necessary materials to recreate a four-box mock-up. He still owned many of the original mould-making materials from the time of Hesse’s studio and used them in the mock-up. The entire process took place in the conservation studios and was videotaped and photographed.

Fig.2

Eva Hesse

Sans II 1968

Installed at Yale University Art Gallery 1992

© The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

The five sections of Sans II are best understood as a quintuplet study – all made from the same container of resin, separated soon after birth and reunited for significant events throughout the course of their lives. Owing to their individual histories, the sections have aged differently and reveal varying shades of yellowing resin and embedded dust. Barger and Sharon Blank, a conservator specialising in modern plastics, worked on a proposal to examine the five sections, research their exhibition and storage histories, analyse samples from each work, and attempt to make correlations between significant factors contributing to various types of ageing. With this in mind, Barger pursued the idea for a Sans II mock-up as an exercise to learn Johns’s specific techniques that might have accelerated ageing: Did he use any UV inhibitors? How precise were his measurements? Was there a release agent? Was it removed? Did he use an accelerator?

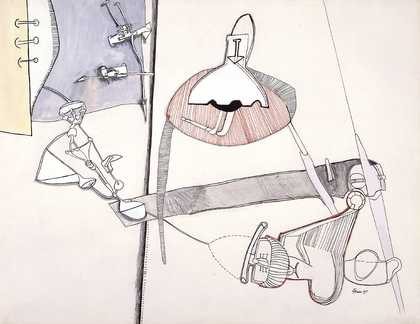

Fig.3

Eva Hesse

Sans II mock-up installed next to original work

© The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

The initial goal for making a Sans II mock-up was to learn more about the process from the original fabricator. Getting a glimpse of what the original work may have looked like was also anticipated, yet no one was prepared for the power of the final product, especially when the mock-up was installed next to the original work at the close of the exhibition. The contrast was startling – instantly bringing to mind Hesse’s comments about striving towards ‘a really big nothing’ in her work.3 The mock-up was presented by Johns during an educational symposium at SFMOMA on Hesse in the spring of 2002, generating a collective gasp from the moved audience. Learning about process was certainly achieved, yet the greater function for the mock-up proved to be the transformative experiential role.

Fig.4

Eva Hesse

Contingent 1969

© The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

In the case study presented above, the mock-up was created for educational purposes. Yet the end result begs the question of reproduction. To explore the appropriateness of this activity for Hesse’s sculptures made from ephemeral materials, one needs to consider the role of repetition in her work. Clearly, this act was at the heart of her creative process, most evident in 1966 with her circle drawings and washer pieces, continuing to her later works including Contingent, 1969. However, actual replication, where elements of a work were reproduced with a mould-making process, were limited to rubber works from 1967–8 (Schema, Sequel, Stratum) and her first fibreglass works with Doug Johns in 1968 (Sans II, Accretion, Repetition 19 III). These works rely on a mould-making process and seem to be limited to 1967–8 – transitional years when Hesse’s sculptural work shifted to a larger scale and incorporated studio assistants in the process.

Fig.5

Mould for Eva Hese, Schema hemispheres

(Spalding ball)

© The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

The technique of replication lends itself well when working with assistants, especially when repetition is a key element in the art work. Yet Hesse abandoned the mould as a means to this end, favouring the variability that comes from hand-made replication of either her model or her verbal instruction. Johns described the process for making Connection as starting with a verbal description by Hesse.4 His ensuing rigid, tightly wrapped connecting sections became Untitled (Ice Piece), a sculpture in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Because this exercise did not result in what the artist envisioned, Hesse was directly involved in a subsequent session with Johns and a second assistant which yielded the much looser and free-form elements that make up Connection. The variability in the elements was encouraged by the artist yet her participation during the whole session controlled the outcome.

Fig.6

Eva Hesse

Detail of Connection 1969

© The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

Hesse never felt comfortable working with outside fabricators, preferring to work with assistants within the walls of her studio. This working style invited a level of variability and randomness in her sculptural work, yet ‘it had to be her random’.5 The idea of full replication of her aged and ‘unexhibitable’ works seems be in conflict with Hesse’s approach. Her works made by using moulds could make better candidates for full replication, yet it seems that mock-ups for educational purposes better honour the artist and her methodology.