Fig.1

Robert Smithson

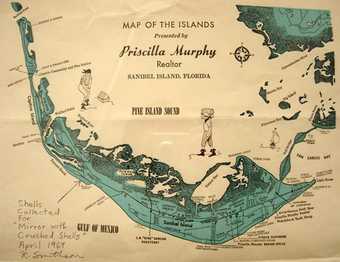

Detail of Mirror and Crushed Shells showing map of Sanibel Island, Florida

© Estate of Robert Smithson / DACS, London/ VAGA, New York 2007

As I try to come to terms with what I have read, what I have heard during the workshop, and what I do as a conservator, I have come to conclude that it is artists who make art. I might go so far as to say that it is only artists who validate art, i.e. something that stands for art in a museum and in the marketplace. Others might exercise or claim the authority – others including studio assistants, fabricators, museum or gallery staff (curators/conservators/art handlers), estates, and collectors – but, in the end, authenticity rests only with the artist. In its wisdom, that is what the law says; rights remain with the artist. As Henry Lydiate writes, ‘under most international and national laws, artists have the statutory “moral right” to object to what UK law calls “derogatory treatment” of their works. This means they can legally object to any addition, alteration, amendment to or deletion from, their original works that damages their “honour, integrity, or reputation”.’ That includes restoration/conservation treatments. Furthermore, as Lydiate explains, ‘most countries have copyright laws that give artists the statutory right to prevent their works being reproduced (and/or such reproductions being merchandised)’. They are therefore assured protection from a replica and the sale of a replica. In most countries, these rights transfer to estates for seventy years post mortem. Thus, artists make art and the authority to protect it from derogatory treatment and replication passes to their heirs. This clarity helps me understand certain artists’ attitudes toward the legitimacy of what they do versus what I do.

Fig.2

Robert Smithson

Mirror and Crushed Shells 1969

Private collection, Houston © Estate of Robert Smithson / DACS, London/ VAGA, New York 2007

On July 9, 1969 Robert Smithson wrote the following letter to Andy Warhol about Mirror and Crushed Shells:

Dear Andy,

This is to certify that the Mirror with Crushed Shells (Sanibel Island) is an original work of art. It consists of three mirrors which may be restored if broken, and one burlap bag of crushed shells collected by the artist at Sanibel Island, April, 1969. If any shells are ever lost, the owner has the right to restore the work by collecting more shells from Sanibel Island (northern part of island – see map of site which is part of the work). The three mirrors are held in place in a corner by the pressure of the shells only. (See photo). The work is owned by Andy Warhol, and can not be duplicated.’Signed Robert Smithson1

In this short letter of twelve lines, Smithson, renowned for a celebration of entropy in his work, has set forth a complex framework of core issues that confronts conservators and curators of modern art. The simplicity of his directives deceptively belies their potential for opening a Pandora’s Box of challenges for those of us thoughtfully engaged in the display of modern art. Let us consider carefully what he wrote.

The first sentence – ‘This is to certify that the Mirror with Crushed Shells (Sanibel Island) is an original work of art’ – at face value authenticates the work but also connotes an apparent need on the part of the artist to substantiate its unique importance, perhaps because it is comprised of non-artistic materials: common crushed shells from Florida and three industrial mirrors. Next, Smithson makes it clear that the ‘three mirrors may be restored if broken’. It is safe to assume that when the artist uses the word, ‘restore’, he actually means ‘replace’.

If we have any lingering doubt about the usage of ‘restore’ to mean ‘replace’, let us consider Smithson’s next sentence. ‘If any shells are lost, the owner has the right to “restore” the work by collecting more shells from Sanibel Island.’ So, Smithson at least condones replaced parts for this work of art but he feels it is his prerogative to dictate in no uncertain terms the parameters of choice for the replaced parts: they must be from a certain place and the artist provides a map to ensure that the exact location is found. In so doing, he maintains control over the character of the replaced shells; any old shell will not do. Smithson is specific and his specificity indicates that the resulting conclusion is a comfortable but precise endorsement.

Now for the final sentence: ‘The work is owned by Andy Warhol and cannot be duplicated.’ So, even though ALL the parts (mirrors and shells) can be replaced, the work cannot be duplicated. By duplication, Smithson undoubtedly means making another piece, i.e. a work that exists in addition to this one, an edition. He draws an important distinction between replacement of parts and making another. Although the artist may not have realised it nor intended it, his instructions offer clear directives to us as to how his work, or at least this type of his work, should be treated in the future.

Lynne Cooke confirms with regard to Richard Serra’s lead/antimony works of 1968–9 that the artist believes ‘switching out individual components in any piece from this group does not constitute a case of refabrication; thus, even if all the components in a work were eventually replaced this would not make the resulting sculpture a replica.’ It might were I to do it, but because the artist made it, he has the authority to do so. Expanding on that notion, Petra Lange-Berndt explains that with Damien Hirst’s art, ‘the concept of originality as something singular has become obsolete … The substitution of the animal [shark] should thus not be rated as surrogation of an original, but as remake: The original frame and concept and a similar shark – they do not guarantee for authenticity but for the continuity of the performance.’ She asks, ‘from which point of time a remake is no longer reasonable?’ What will happen, for example, when Hirst can no longer personally direct the remakes through Science Ltd?

After an artist dies the authority to protect the work of art transfers to the artist’s estate. Estates have a right to protect against replication by others, e.g. exhibition copies. Some estates also exercise the right to replicate for sale and I gather from some papers this practice raises discomfort, even outrage, among you. It is a seemingly small step but actually a giant leap from ‘not for sale’ exhibition copies to posthumous works authorised by estates and other representatives of the artist for profit. One cannot help but think of the legacy of Yves Klein and the 1,281 known posthumous editions (copies) of four of his known works. In 1999 there appeared a catalogue of the posthumous works that was billed as ‘the definitive catalogue of the editions and sculptures’.2 In his introduction and defence of the project, entitled Matter and the Immaterial, Pierre Restany explains: ‘This little book is far from useless and arrives just at the right time. It is more than a message of faith in the Artist and in the spiritual impact of his work; it is also an exhaustive guide to the production of the Multiples, a meticulous catalogue of the editions.’

We learn that in order to make the editions, the restorer (Jean-Paul Ledeur who knew Klein) used an existing original mould or a cast taken from the original piece. The materials were identical (as far as possible) to those used in the first pieces. Each piece comes with a certificate containing a photograph of the piece, its number, and the widow’s signature. When one edition was finished, the moulds were systematically destroyed.

The restorer and author of the catalogue explains: ‘In every case, and following the example of the original model, each piece is painted three times using a paintbrush, then three times with a fine-spray paint gun from different angles. The result is a hand-painted piece – the brush marks are clearly apparent – with the velvet quality and pictorial transparency defined by the artist.’ Lest we wonder whether or not these editions are to be publicly exhibited, he confirms, ‘And, of course, we must not forget the presence of the editions in retrospectives of Klein’s work.’

A catalogue of posthumous works may be helpful in sorting out the legions of blue objects but they are not art works by Yves Klein or are they? How do we restore them? Do we treat them as originals and restrict our inpainting to scratches or do we send them back to the restorer who made them? Or, do we repaint them ourselves using the same materials and techniques? Are they Yves Klein ‘editions’ or are they merely simulations? Their status has a direct bearing upon how we, as conservators, choose to treat them.

Their undetermined status contributes to another potential problem. As Lydiate points out, ‘a related, less certain and even more complex issue is the impact on the market value or works from their being replicated … It is therefore important that anyone (artists, their estates, museums, and collectors) contemplating replication or authorising the lawful replication of work bear in mind the potential economic damage that may befall owners of the original pre-existing work(s).’

What if this motivation to replicate is ostensibly not for the purpose of sale but rather for installation in museum exhibitions? Natalie Leleu-Bertrand describes the reconstructions of Tatlin’s lost Model of the Monument to the Third International in Stockholm (1968), in Paris (1979), in Sweden (1980) because of damage, and in Moscow (1993) by various curators. Leleu-Bertrand explains, ‘The French and Swedish collections today own two artefacts born neither from the hand nor the will of Tatlin.’ And then there is the third one. ‘Neither from the hand nor the will of the artist’, these copies are ‘archivally’ made for exhibition/education purposes only, i.e. for the public. This practice can become particularly complex for museum personnel. Susan Lake notes that some objects are replicated – remade – each time they are shown. Drawing from her experience with sundry instances of replication, she concludes ‘artist’s actions, which are fundamentally redefining the terms of artistic production and replication, are having a profound impact on the Museum’s attitudes and practices.’ Alistair Rider acknowledges that ‘as objects appear ever more short-lived, museums … become storage areas for authenticity and uniqueness per se … they also become the institutional expression of art’s value in providing a counter-world to the realm of the factory-produced, mass-manufactured object.’ Is that assumption still true?

Perhaps it is changing as museums become ‘factories’ of works of art – producing exhibition copies for installations and even making replicas. Rider and James Meyer cite respectively Carl Andre’s and Dan Flavin’s fury over unauthorised installations of their work. Meyer also brings to the table the highly controversial realisation of Donald Judd sculptures from certificates by the collector Giuseppe di Panza. In the end, neither Andre, nor Flavin, nor Judd was (as Rider writes of Andre) ‘wholly prepared to relinquish full or absolute authorial control over the finished work’. In Meyer’s words, with regard to the Panza affair, ‘The collector considered them works of art; Judd did not. According to Judd, the only authentic works in Panza’s collection were those that had been built at Bernstein Brothers. The paper works that Panza had managed to build … Judd dismissed as “fakes”.’ Judd did not oversee their making. He did not make the decisive choices in the creative process, e.g. the determination of when they were finished. Therefore, to the artist, they were not his work no matter how legal their making.

In short, they lacked an aura associated with Judd – whatever that might be. In deciphering Walter Benjamin’s thoughts, Maggie Iversen astutely positions the dilemma in light of a world in which the ‘desire for auratic, aesthetic experience is always threatening to collapse into the copy and the commodity’. She concludes, ‘The difficult task of the museum is to conserve the work of art and where necessary even replicate it while protecting its vulnerable aura.’ Therein lays the problem. The replica by its very nature is not (to use words uttered in this workshop) ‘original’, ‘free’, ‘imperfect energy’. Yet, to be convincing, it must have punch – aura. Are these requirements not inherently contradictory?

Perhaps we must take a closer look and attempt to categorise replicas according to their guiding motivation. What might those categories be?

- Replica made by the artist.

- Replica as documentation and didactic aid to understanding, i.e. a document of lost, irreparably damaged, never made work of art.

- Replica as replacement of individual parts – not unlike ‘inpainting’ of damaged or lost parts of a painting.

- Replica that gives life to a concept by capturing its magic and aura. This work might be put on public display and could potentially over time make its way to the marketplace.

- Replica that assumes the status of art by taking something the artist made but never considered as art.

- Replica that represents something the artist wanted to make and would have done so but never did.

Let’s try to distinguish and assess the authority of these types of replica by starting with a replica made by the artist.