The place to begin this essay is with the artist it is built around: Henry Moore. Yet despite this tight focus, its aim is not to retell a perhaps too-familiar life but instead to summon a more neutral version of the man. Enter Moore, then, in his identity as a British citizen (fig.1), a status that won him the right to travel freely in the post-war world. Which he energetically did, as his passport attested . Issued in 1955, this was the document that in the following next twelve months or so, took him to Paris, Zagreb, Auschwitz, San Francisco, and the south of France, each trip contributing to the apparently irresistible process that, over the next decade or so made Moore the public face of British art.

It might be useful to think of Moore, not as that much applauded public figure, but instead in the terms his passport sets out: the absolute basics of the citizen’s self. In 1955 the authorities required only minimal facts: half a century ago it was sufficient merely to identify the bearer as an artist-sculptor, born in Castleford, residing in England, a fifty-seven year-old man with ‘blue grey’ eyes and ‘fair grey’ hair, where blue grey names a colour and fair grey means fair hair that is going grey. As for his height, Moore was five feet, six and a half inches tall. By contemporary standards this is modest: these days the average British man is five feet ten inches, the average Scandinavian a few inches more. Doubtless the difference – the changed dimensions of the British body then and now – could be asked to speak to Moore’s Yorkshire origins, his birth as the seventh child and fourth son of Mary Baker, a miner’s daughter, and Raymond Spencer Moore, a miner himself.

There is no question that Moore’s coal-country roots mattered keenly to his sense of self. The Tate archives offer unusually immediate, and hitherto unnoticed, evidence that this was the case. It comes in the guise of a printed form that the Tate Gallery used, presumably in the early 1940s, to collect biographical details from the artists represented in its collection (fig.2a and b).1 (This may have been an initiative launched by Sir John Rothenstein, the Tate’s director from 1938 until 1964. In any event, it was sent to Moore under the Director’s name.)

The form’s questions are fairly prosaic, but Moore’s responses are not. They stand out for the care he took to supply the requested ‘particulars as to family history’. He even went so far as to provide a family tree. Not only does his diagram reach back unto the fourth generation (note that when he came to his great grandmothers – not fathers – he is at a loss to say precisely who they were), but it also reports the names, Annie through Elsie, of all his sisters and brothers: his was a family whose four boys were balanced by four girls. Yet as any graphologist would testify, it is the artist’s name in the new generation that grabs our attention; Henry is the one who matters, the one he himself declared most solidly, assertively, a Moore.

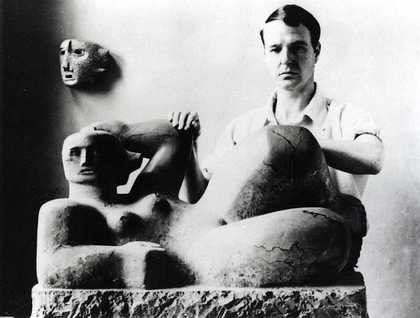

Fig.3

Henry Moore with Reclining Figure and Mask, c.1930

The Henry Moore Foundation Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2011

It was Tate curator Chris Stephens’s remarkable Moore retrospective in 2010 that, for this writer, became a catalyst for reflecting on Moore’s stature in literal, as well as figurative terms.2 This line of thinking began inside the exhibition itself, where the installation allowed visitors to stand behind Moore’s 1929 Reclining Figure, and from there look out at the exhibition space. Doing so triggered a memory of a photograph of the artist showing him in the same location, behind the identical Reclining Figure, both hands proudly on the finished work (fig.3). Occupying that position produced an odd sensation. A piece that over the years had been growing increasingly massive in recollection began to seem quite delicate, with its new smallness underscoring its relation to Moore’s body, and asserting a likeness to mine.

And the same might be said of the other sculptures that were chosen for the show, regardless of whether photographs exist of Moore standing beside them, and if there are, who else happens to be there, too. This sense of a parallel or resonant bodiliness is characteristic of objects that, whether cast or carved directly, stemmed from a process that put the artist face to face with his chosen material, weighing its bulk against the force of his body and tools. Many of the early photographs of Moore in his studio stand as emblems of those close encounters: they insist we keep the bodily back-and-forth between artist and carving vividly in mind.

In fact, it seems right to say that all of Moore’s pre-war carvings retain the bodily immediacy of the process that made them, and offer that immediacy as an effect of the scale and presence of the works. One great accomplishment of the 2010 exhibition emerged directly from its clear grasp of this particular aspect of Moore’s production, which served as an experiential thread from beginning to end. The show, in other words, found a way to allow the work to relate directly to its viewers’ bodies – which not all exhibitions manage to do. The result was something – a traffic, a trade-off – between animate and inanimate presences, an exchange that, in a remarkable series of images, Tate’s photographers paid close attention to and managed to convey (figs.4 and 5).

One further outcome of the retrospective cannot be illustrated quite so neatly. It is that by so concertedly demonstrating the immediacy of the bodily relationships animating the works it selected, the show also inevitably summoned the unquiet ghost of the objects it had excluded: the many large bronzes from the 1960s and after, which were responsible for Moore’s international fame and, by extension, his artistic passport abroad. If Moore’s monumental public sculptures do not have the immediately resonant embodiment of his smaller pieces, then what do they have instead? After the war, it is fair to say that Moore no longer left his mark on his sculptures in the literal sense, as was the case with his earlier work. His working processes had changed. The new way of working meant that he was routinely dwarfed by the objects produced in his studio, as viewers were too. Looking at a photograph taken in a Perry Green workshop in 1969, it is hard not to see the artist as tending to an enormous and demanding body, a bit like an elephant keeper caring for his charge (fig.6).

Yet, the photograph notwithstanding, it was not Moore but his assistants who did most of the tending. When a commission was received, they were the ones who scaled up plaster-clad enlargements from a stock of studies, or maquettes, as he called them. A sculptor usually makes a maquette when she or he has a particular commission in mind. Small studies by Moore, however, were not necessarily remade at larger scale. Often they began from found objects, one alone or two coupled together, but in any case, hand-sized things that famously, Moore could hold, turn and omnisciently inspect from every point of view. To make these works, unlike their later incarnations as monumental plasters, he needed no help from anyone. Nor was he necessarily thinking at the outset of a future work. Instead for him, the maquette’s smallness was a way of getting round the inherent constraints of size and patronage. To quote him directly: ‘I don’t make my maquettes and models for that purpose of trying to show to somebody else what the big one was going to be like. No, as I make this, the size is any size that I like. I can make it any size in my imagination that I want it to be.’3

A maquette, Moore is saying, if not quite a utopian object, is at least a law unto itself, governed only by the artist’s mental image of how it would take its place in the world. Such an object is as divorced from the constraints of patronage as a work of art can be: it was not necessarily destined to have a future life. An active decision had to be taken for a maquette to be remade, at this point not necessarily in the size Moore ‘liked’, but instead in the one the eventual patron, with Moore offering guidance, decided to choose.

For that expansive process to happen – it involved changes that doubled or tripled, sometimes even quadrupled the physical size of his objects – Moore’s studio also had to change. His own tasks became increasingly focused on creation and supervision, while a crew of assistants came up with the technical solutions needed to make monumental sculpture, and supplied the necessary labour up to the point when the final full-size plaster had been completed and a bronze version was ready to be cast. After the early 1950s casting was never done on-site. And for all intents and purposes, Moore’s actual physical labour on his sculpture had by then come to an end; the many photographs that show him apparently working away with the chisel represent what his assistants called ‘Saturday afternoon sculpture’, only performed for the camera (this according to Derek Howarth, one of Moore’s assistants in the mid-1960s).4

This new process changed the shape of Moore’s career – his stature, once again. The increased scale of his sculptures directly increased his critical reputation and, as a consequence, the number of commissions he received. So much is obvious, but it is still essential to measure how far these changes went. Considered simply in terms of the studio’s output, it would show something like a sixty per cent increase in average annual production from 1949 to 1986, the year of his death at the age of eighty-eight. Astonishingly, during the last few years of his life, from 1980 onwards, in terms of sheer volume, Moore’s studio was proportionally more productive than ever before.5

What are the perceptual and conceptual implications of such radical expansion? Might it be worth asking whether Moore’s transformation of his practice served some particular set of aesthetic purposes – if it really did offer him some of what he ‘liked’ – rather than simply corresponding to the laws of supply and demand? The response this essay offers is a qualified affirmative, with the essence of the argument resting on Moore’s innovative attitude towards scale.

What does scale means where sculpture is concerned? The question needs asking because scale is not the same as size. On the contrary, scale is the appearance of size, which may or may not stand up to verification by objective means. Which is to say that as a perception, sometimes even an illusion, the scale of an object is how big or small it looks.

And like most appearances, scale is deceptive, never more so than when an object or image lacks a necessary frame of reference and thus functions as a law unto itself. Yet paradoxically, scale can also be what cuts such deceptions down to size. Adding scale to a view or an image, as all vacation photographers can testify, requires the use of an ‘external’ yardstick, a human figure, for example, or indeed anything whose size we think we know. Usually the addition – think red-faced tourist clinging to the Great Pyramid – looks strange, its presence signalling an alternative, and often lesser, order, a separate truth. Or as the art historian Andrew Causey puts it in an essay on Moore’s drawings, scale is ‘added in a different language’.6 When it is absent, one is all too often at sea.

In short, scale is comparative or relational, as well as contextual; a frame that helps us place objects within the physical world. To assess the scale of something is to place one dimension, measurement or object against another, so as to gauge the differences the comparison draws out. Even so, scale does not always speak in measured terms – smaller or larger, say, or with an inch doing duty for a mile. Instead, its tone can be subjective, even vehement, loaded with rhetorical force: ‘Two vast and trunkless legs of stone’ to borrow the poet Shelley’s well-worn phrase.7

But another rule also governs scale. As a visual effect, it is unstable. An object’s dimensions may be altered according to carefully observed mathematical calculations, yet the effects of these alterations are not necessarily either stable or predictable. Strictly observed principles can be used to swell or shrink a sculpture, but precisely where that process will lead cannot be foretold. The final look of a work depends on context and vantage point, more than anything else. And as Moore’s assistants knew well, adjustments were often needed to accommodate an enlargement to the duplicity of sight.8

This is why nearly any diagram one might use to support this point returns us to the fundamentals of perceptual psychology. Everyone will remember one or another illustration of the fact that it is the immediate environment of any figure or image that determines its apparent size. To provide the simplest possible example, here is a set of linear diagrams in which difference emerges and sameness is lost by nothing more complicated than bracketing an identical line on each end by visually opposite shapes (fig.7). The different additions alone are enough to transform our reading of all three.

Or, to invoke an example that comes closer to the subject of sculpture, there exists a photograph of Moore standing with Michael Heseltine, then Secretary of the Environment, at the 1980 inauguration in Kensington Gardens of a travertine version of The Arch.9 The push and pull between the two human figures and their colossal marble framework is truly peculiar, most of all because the pairing of men of such different heights provides two distinctly different yardsticks to gauge the arch’s scale. The image is telling enough, but if further proof were needed that scale is an unexpectedly visual phenomenon, we can simply imagine it without the honourable Secretary, a subtraction which immediately allows the image to make much more visual sense.

It helps to know, when considering the relationship between scale and the studio, that the Kensington version of The Arch was the last in a series that began from a maquette made in 1962, and now housed in a cabinet at Perry Green. Moore based the model on a salvaged animal bone from which he made a clay or plaster squeeze mould and thence a quick plaster cast. The result is tiny, only eleven centimetres high (by contrast, the Kensington travertine is over 5.6 metres in height). Between these two extremes are a half-sized polystyrene model for a six-metre polystyrene version, which then was given a thin surface in plaster and used to produce a six-metre bronze cast in an edition of three, one of which now stands before the Cleo Roberts Memorial Library, designed by architect I.M. Pei, in Columbus, Indiana, and shipped there from Hermann Noack, Moore’s Berlin foundry, in 1971. And finally there was also a six-metre fibreglass version exhibited at various locations; most dramatically in 1972, as a crowning element of a triumphant show in Florence, with the city at its feet, and then with somewhat less drama, as a component of the Serpentine Gallery’s 1978 exhibition that celebrated Moore’s eightieth birthday.fn]Restored in the summer of 2010 at Perry Green, The Arch was on view in Paris in the courtyard of the Musée Rodin from 15 October 2010 to 27 February 2011.

A potentially bewildering accumulation of versions and sizes, their multiplication is precisely the point. At least six materials were involved in the facture of the works since the composition was first arrived at in 1962: bone, plaster, bronze, marble, polystyrene, and fibreglass. And this accounting omits components that cannot be seen with the naked eye. To look beneath the surface of the plaster would have been to discover webbed strips of hessian soaked in plaster so as to flesh out the wooden armature that lay deeper still. In the case of the bronze, by contrast, what is to be looked at is the surface, which was cast in fifty pieces, and then welded with invisible seams before the chemical patina was applied. The seams on the polystyrene version, by contrast, are fully visible, not least given the dark cement that marks the joins of each building block, and recalls the initial hot-wire cut. And inside the fibreglass version, are wide-spaced stiffening lengths of what is likely to have been recycled wood (fig.8).10

Much more will doubtless come to light about the mushrooming of Moore’s production processes from the later 1950s onwards, and the aesthetic and conceptual transformation of the sculptural object that results. That is, if one believes such a transformation did take place in the last twenty-five years of Moore’s working life. Such a claim would presume that the growth of his reputation (and wealth) involved more than the invention of Moore as a cultural commodity and national myth. Moore’s standing certainly changed: the headline writers had their inevitable field day, and phrases like ‘culture star’ hit the press.11 But I still think it is important to take stock of the exploding visibility of Moore’s later work as both symptom and result of the new heterogeneity of his imaginative and technological means.

That diversity breaks down into what we could call stages, but not if that vaguely managerial terminology hides how fundamentally different each is where scale is concerned. First – think back to the The Arch or to any of the hundreds of studies crowded onto the shelves of the studio – is the maquette and its parent, the found object. I have already pointed to Moore’s use of found objects as a point of departure, a practice that, if not strictly Duchampian or even surrealist, still made appropriation and play its guiding light. Who can image André Breton having a wander across the Suffolk shingle or Marcel himself poking along Perry Green’s lanes? Whereas even to begin to understand Moore as a maker means starting with an idea with someone constantly looking about him, especially down, then pocketing his finds for inspection later on. The habit was his way of bringing bits of the world up close. Never mind that doing so meant stripping away an object’s natural context, its fixity, in favour of a new and oddly placeless, scaleless vision; – its new surroundings were not the studio, but the mind’s eye.

What is striking about this first phase is how distinct it is, as a regime or activity, from the rules that governed what happened next: not imagination but measurement. And not random or discarded bits and pieces of organic matter – ‘Nature’ – but culture, or better, material culture, as its diverse production processes could be drawn on in the service of his work. Moore’s sculptural practice returned, in a fashion that in retrospect now seems almost effortless, to traditional ways of working: to the history of sculpture, and how the studio as a site of production had always worked. And then, with similar lack of effort, these traditional methods were re-mastered along lines opened by the post-war production of plastics: polystyrene came to Perry Green.

Historically speaking, the sculptor’s studio was nearly always a site of both production and reproduction, where the tools and skills of accurate measurement were commonly employed. Consider, for example, the interior of the artist Antonio Canova’s (1757–1822) workshop in Rome, as depicted in a watercolour by Francesco Chiarottini from c.1782, an image published in the Burlington Magazine by the art historian Hugh Honour in 1972, just after Moore’s practice settled into its latter-day form (fig.9).12 On view are plaster models and marble enlargements, plus the assistants and their tools needed for enlarging. Furthermore, two basic systems to do so are also laid out for view. Both depend on back-and-forth measurement, whether by means of the metal calipers propped beneath the figure of Humility, or via the three wooden frameworks suspended above the other monumental figures in the studio (from which parallel plumb lines are to hang).

A scant two centuries later, and Moore and his assistants had revived many of these same old methods of measurement for post-war use. No doubt in at least a few other ateliers, they had never been abandoned. But Moore began by putting them aside. During his early career, when direct carving was preferred, measuring devices had no use in his studio, but during and after the war, this changed From these years date his first editioned bronzes; in the photographs that record the everyday jumble of his workplace, the artist’s plaster-soiled calipers crop up in the general accumulation of saws, shells, a scrunched-up paper, moulds and flints. And there are shots of the artist and his assistants that show this ancient device in active use. Occasionally there is a glimpse of a measuring frame and plumb line, as in an informal snapshot taken in the margins of a professional photo shoot: a bowl of plaster at the ready, Moore is shown posing for the unseen John Hedgecoe, while off to one side, there must have been a second camera that captured the workaday clutter along with the artist carving on cue.

It is possible to overemphasise the echoes in Moore’s practice of sculpture’s more, rather than less, technologically developed past. The differences count too. There is the considerable fact that his team was put to building larger and larger plaster models to serve in the casting process, while Canova’s, for example, was more often able to go directly from the smaller model to the larger final piece. Working for Moore required knowing more about carpentry than carving, so much so that it is tempting to see a repressed constructivism beneath or within the endless plaster mock-ups, and the studio photographs as witnesses to a buried kinship with constructivism’s origins in the skilled carpentry of the Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953).

Which is to say that Moore’s plasters might betoken modernity, as well as tradition, although not as much as do the production methods used in the final stage of his work, methods which derive from his use of polystyrene as a light, fast and cheap method of scaling up. These lightweight models themselves were often re-made in various sizes, and demanded adaptation to achieve the right surface for the final bronze. Even so, with considerably less effort on the part of the artist and his studio, a patron could get a good sense of how a final work would look.

Working with polystyrene demands considerably more precision than plaster or clay; shaped by means of an electrically heated wire, it does not tolerate errors or forgive artistic changes of mind. Hence in the Perry Green studio the old methods of measurement were updated, and new ones evolved. The Henry Moore Foundation has found ways to put some of these working processes on view. Visitors today can look inside a small plastic-walled studio that has been fitted out to suggest a version of the huge light-filled space – a quasi-greenhouse – that the new, larger sculptures demanded. Rather like a display in an anthropology museum, it shows a new and adaptable version of a measuring frame, a device that, instead of hanging statically above the sculptural model, can be moved along it in order to record its three-dimensional coordinates stably and consistently, while bringing them into relation with the gridded ground plane on which the model sits (fig.10). On other occasions the method was more simply subtractive, when the execution needed to be more finely grained. Here the small model sat on a sheet of squared paper, while the enlargement, resting on a scaled up version of the same grid, was shaved, scratched and even grated away (fig.11). It is one of the better known ironies of the years of Moore’s celebrity as a civic artist that his bronzes were often given texture – the look of carving – by using a domestic grater of the sort designed to face up to carrots or cheese.

Fig.12

Photograph of Henry Moore’s Large Standing Figure: Knife Edge 1961, seen at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, Wakefield, October 2010

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2011 Photo: Anne Wagner

Why focus on such breaches in the time-honoured protocols of making? Because these various expedients make clear that Moore’s studio kept hold of a workshop mentality, cooking up solutions as problems arose. Sometimes they worked. If they did not, it was sometimes because the young men who built the models did not know quite how to do what was asked. Perhaps their toughest task involved compensating for distortions in scale. For while width and height grow arithmetically, volume grows geometrically. And the viewer does not grow at all. Shapes become inert and lose definition, or what Moore called their ‘edge’. All sculpted objects share this basic property of objecthood: they deal in edges, backs and sides. They separate themselves from their surround. Moore used the phrase ‘knife edge’ to title more than one of his monumental bronzes. Looking at the earliest of these, Large Standing Figure: Knife Edge 1961, it is easy to see something of what that epithet conveyed: the way a work lays claim to both space and time (fig.12).

There is something both painful and magnificent in learning that this elusive, turning, dancing, spectral figure started its life as a chicken bone. No more, no less. A bone salvaged from somewhere, the precise location unknown. Its transformation into an enormous standing figure resulted from the sculptural processes this essay has tracked. Transformation, yes, but without the founding sense of boniness ever quite fading from view. In an essay published in 1951 – one of his first on Moore – the art critic David Sylvester offered a useful term to name the combinatory process that keeps those origins alive. He called it substitution, a word that with its psychoanalytic aura (it recalls Freud’s lexicon of psychic operations, starting with condensation and displacement in the dream) invites viewers to think about the emotions this hybrid figure calls up.13 Or the knife edge it balances on: between line and plane, between animation and stillness, between aliveness and death. Much about the uncanny presence of this object derives from the processes that made it, and from Moore’s disruption of expected indices of scale.