During its first ten years, the São Paulo Biennial established itself as a central meeting point between Brazilian and international art. The biennial was inaugurated in 1951 at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM-SP) under the direction of the museum’s founder and president, Ciccillo Matarazzo, using the Venice Biennale as a model, with countries presenting ‘national pavilions’, or displays of art. Despite its international success, the project was beset by internal and financial crises. Matarazzo wanted to focus the museum’s scarce resources on the biennial, attracted by the ‘immediate prestige’ it brought the institution, and was frustrated by the lack of support from the museum’s directors.1 In 1962 these tensions came to a head and Matarazzo decided to separate the two institutions: responsibility for the exhibition was transferred to the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo (FBSP; a private foundation led by Matarazzo), and the following year the museum was dissolved.2

The FBSP was criticised in the national press during the 1960s for its mode of organisation and increasing divergence from the artistic community in Brazil.3 While some critics, such as Marc Berkowitz and Olney Krüse, complained that Brazil was exclusively represented in the biennial by artists adopting an international style, others such as Aracy Amaral and Paulo Mendes de Almeida criticised the excessive number of Brazilian participants. It was in this context, informed by art critical debates concerning the representation of national art, that the FBSP proposed a parallel exhibition of Brazilian art, to be organised in alternate years to the international biennial.4

The development of the national biennial in the 1970s reflected ongoing debates concerning the nature of an authentically Brazilian art. An interest in establishing a Brazilian mode of artistic expression can be traced back to modernist movements of the 1920s such as Pau-Brasil, anthropophagia (cannibalism) and verdeamarelismo (green-yellowism).5 Artists associated with these groups often used formal structures appropriated from ‘primitive’ Brazilian art to position a sense of ‘otherness’ at the centre of the discourse of the avant-garde.6 The 1970s saw the re-emergence of this search for a national aesthetics in such movements as Indianism, marginalismo, arte negra and sul americanismo,7 which shared a drive to expand the geographical limits of Brazilian art beyond a Rio de Janeiro–São Paulo axis.

Criticism of the São Paulo Biennial was directed at how artistic practice was framed (and consequently legitimised) by exhibitions that did not acknowledge the artistic and cultural differences contained within Brazil. The exhibition’s organisational model, almost unchanged since its first edition, was constantly questioned. In 1968 the Brazilian Association of Art Critics sent a letter to the FBSP demanding structural reform of the biennial:

The FBSP, whose cultural and artistic presence in Brazil has been of extraordinary value for our development, has shown in its operation several administrative and cultural deficiencies. These deficiencies are, of course, not the direct responsibility of any of its leaders, including its eminent president and founder ... The crisis at the São Paulo Biennial is of a structural nature. It can no longer be conducted in an improvised and amateurish way ... For its survival, a complete restructuring is required, taking into account all administrative, museographic, cultural and pedagogical aspects. This restructuring requires, in the first place, a profound reform of its statutes and regulations.8

It is reasonable to assume that the emergence of a national biennial during a period of dictatorship suggests a nationalistic alignment between the FBSP and Brazil’s repressive civic-military regime, in power between 1964 and 1985. It is perhaps for this reason that the short-lived ‘Bienal Nacional’ does not feature more prominently in the published historiography of the São Paulo Biennial. The exhibitions themselves were under-documented, with few photographic records, but the development of the national biennial is detailed by the FBSP’s organisational documentation, is addressed within its catalogue texts and was discussed by art critics within the country’s mainstream and specialist press.

The four national exhibitions held between 1970 and 1976 had marked differences in both function and organisation. The purpose of the São Paulo Pre-Biennial (1970) was to select Brazilian artists for the international biennial of the following year (eleventh São Paulo Biennial, 1971). The national biennial of 1972 comprised two distinct but concurrent exhibitions: the experimental Brasil Plástica 72, organised by the FBSP, and the nationalistic, state-sponsored Exhibition for the 150th Anniversary of Independence. The first exhibition to be officially named a ‘National Biennial’ took place in 1974 and was again used as a way of selecting Brazilian artists for the São Paulo Biennial. This selective function, however, was discarded during the fourth and final National Biennial 76, for which the jury chose to accept every artist registered for participation – a controversial decision which they justified as a means of presenting a true picture of Brazilian art.

Towards a national biennial

Following the creation of the FBSP, the prospect of a national biennial began to pick up momentum. The idea, however, had emerged earlier. The São Paulo Biennial was structured around national delegations, but it also included special rooms organised with guest artists, which were exempt from the jury. The biennial was criticised for the large number of guest artists, and because the special displays favoured the exhibition of Brazilian art to the detriment of international art. In a 1961 article published in the Estado de São Paulo, the art historian and critic Aracy Amaral asked: ‘Where will Brazilian representation end if we do not take action, with the constant increase in the number of artists “exempt from jury”, on top of approved candidates and special rooms?’9 Amaral suggested the biennial establish an invitation system for Brazilian artists, similar to that used for participating nations, with the MAM-SP ‘obliged’ to travel across the country to ‘get in touch with multiple groups from several cities’.10 The following year, MAM-SP’s Director, Paulo Mendes de Almeida, echoed Amaral’s position, commenting that it was ‘simply ridiculous that each biennial exhibits every artist in the country’,11 and suggested the museum should host short exhibitions as a way of pre-selecting artists for the biennial.

Five years later the idea for a national display re-emerged, partially in response to the criticisms levelled at the ninth São Paulo Biennial (1967), both for the continuing indiscriminate over-participation of Brazilian artists and for its suspect organisational structure. Mendes de Almeida wrote that ‘Brazil lost the opportunity to become the best, among all the 9th Biennial representations’, its display weakened by ‘an excess of artists and, consequently, of works that did not deserve to figure there’.12

Much criticism of the 1967 display was directed towards Matarazzo and his dictatorial attitude towards the organisation. A letter from the International Association of Plastic Arts (AIAP) addressed to the Governor of the State of São Paulo addresses the controlling administration of Matarazzo:

It is no longer permissible for Mr. Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho ... eternal president of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, to have public funds for personal promotion, in his eagerness to perpetuate himself as Patron of Brazilian art. Since the second Biennial, the aforementioned gentleman has not been the sponsor of the exhibition, therefore he must listen to the real will of those who make art in Brazil, the artists, and to bow to the dictates of a true national culture.13

In response to these concerns, a Technical Art Commission was created, composed of three members suggested by the FBSP and three others suggested by the AIAP and the Brazilian Association of Art Critics (ABCA).14 The group wanted to transform the format and regulations of the biennial but ultimately only a few changes were achieved: the criterion of medium was eliminated as a category for selection and awards, opening up a definitive space for interdisciplinary works; and the minimum limit of works by artists was abolished, as were invitations for participation by artists and the acquisition awards. The reluctance of Matarazzo to implement more of the Commission’s proposals led two key figures – Luiz Fernando Rodrigues Alves (Director Secretary) and Radhá Abramo (General Secretary) – to request their own dismissal.15

In this context, facing pressure from associations, critics and artists, Matarazzo recognised the need to publicly address the format of the biennial. In a short note published in the Diário de São Paulo, the idea for a national display was attributed to a suggestion made by Matarazzo in February 1967:

With the objective of giving Brazilian representation more quality in a smaller number of artists and works included in the biennials, and changing the criteria for selection by national juries, the Advisory Commission of the ninth São Paulo Biennial received a suggestion from the president of the Foundation, Mr. Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho – to study, for 1968, the realisation of an exclusively national biennial. In this way, in even years there will be an exhibition to be considered a preview of the biennials of the odd years, which would serve to select Brazilian artists and, consequently, allow our representation to impose its possibilities with greater emphasis.16

The creation of a ‘Pre-Biennial’, he suggested, would both encourage a broader analysis of ‘national art trends and activities’ and, with artists selected by a well-organised jury, ensure that artists with a developed practice and appropriate ‘rank’ would represent Brazil at the São Paulo Biennial.17 As the idea matured, the FBSP engaged specialist advice via the ABCA and the AIAP. The President of the ABCA, Mário Pedrosa, suggested that the FBSP should send a Pre-Biennial jury to larger regional cities in order to reach artists outside the Rio–São Paulo axis.18 The Pre-Biennial was initially planned for 1968,19 but the FBSP’s continuing internal crisis meant the event was postponed until 1970, the year after an international boycott of the tenth São Paulo Biennial (1969).20

Pre-Biennial 1970

Fig.1

Cover of the catalogue to São Paulo Pre-Biennial 1970, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo 1970

Courtesy Bienal de São Paulo

The catalogue of the 1970 São Paulo Pre-Biennial introduces ‘a broader vision, almost a global panorama’ of Brazilian visual art (fig.1).21 In order to select artists from across the country, the FBSP supported regional exhibitions in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais), Recife (Pernambuco), Brasília (Federal District), Goiânia (Goiás) and Belém do Pará (Pará). Each exhibition had its own jury, which selected artists to send to the Pre-Biennial. Other states organised their own means of selection, and the 258 artists who exhibited in São Paulo represented every Brazilian state with the exception of Piauí and Maranhão. On the day of the exhibition’s inauguration, Matarazzo announced the São Paulo Pre-Biennial as ‘a way of making contact with the current Brazilian art scene, which will be increasingly broad in the future’.22

Fig.2

Wanda Pimentel

Involvement Series 1968

Vinyl on canvas

1300 x 980 mm

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

The task of selecting which of the artists exhibiting in the Pre-Biennial would go on to represent Brazil at the eleventh São Paulo Biennial (1971) was undertaken by a jury comprising the North American curator James Johnson Sweeney, the Argentinian art critic Romero Brest and three Brazilian members, the artist Hugo Auler and the art critics Marc Berkowitz and Lisette Levy.23 The jury selected twenty-five artists from the Pre-Biennial exhibition to participate in the international event.24 Among them was Wanda Pimentel from Rio de Janeiro, who was an active participant in Brazil’s circuit of contemporary art salons. Pimentel participated with five paintings from her Involvement Series, made between 1968 and the mid-1980s (fig.2). These works depict brightly coloured domestic spaces which combine modern consumer objects with the fragmented female body.25

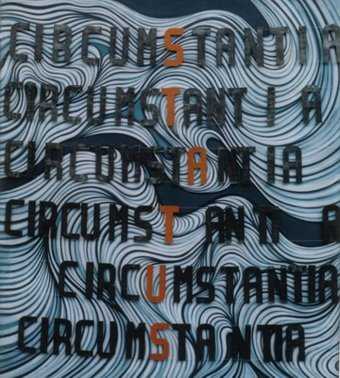

Fig.3

Humberto Espíndola

Circunstantia – Status 1970

Oil on canvas with collage

1720 x 1520 mm

Collection of the artist

The geographically expansive selection process also brought art from regional locations into focus. Humberto Espíndola, for instance, showed his acerbic pop-like explorations of ‘bovinocultura’, the culture of cattle-raising that defined his home state of Mato Grosso. The artist exhibited five paintings at the Pre-Biennial: these were Pantanal: Paisagem 1970; Pantanal: Beef Cattle 1970 (collection of the artist); Cattle Farming: Circunstantia 1970 (collection of the artist); The Badge 1970; and From Landscape to Coat 1970 (collection of the artist).26 His works from this time are painted in vibrant colours – red, yellow and blue – with thick black outlines. Objects such as letters, knives and barbed wire are aggregated onto the surface of the canvases, suggestive of the works’ critical position towards the state (see, for example, Circunstantia – Status 1970; fig.3). The barbed wire, for instance, refers to fences built to control oxen, used by Espíndola as a metaphor for the political moment in the country.

Like the international biennials, the Pre-Biennial had a special room intended to honour a single artist. The artist chosen was Geraldo de Souza, who was registered for the Pre-Biennial but died in May 1970.27 De Souza’s paintings are subtle geometric abstractions in ochre and earth tones.28 His works reflected an aesthetic shared by São Paulo’s Grupo Vanguarda (founded in 1958), which played a leading role in the creation of both the Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Campinas and its annual Contemporary Art Salon (1965–77).29

These three artists represent the range of work highlighted by the first national biennial, which aimed to provide a more rigorous selection process for the Brazilian delegation at the eleventh São Paulo Biennial of 1971, and to consider artists from throughout the country. Hugo Auler described the Pre-Biennial as a ‘rare artistic and cultural event’ that had, despite the risks inherent to any experimental process, achieved ‘positive results in the context of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo’s excellent idea’:

[A]rtists from the most diverse regions of the country had a state-wide reach, and at the same time, those selected, when presented at the Pre-Biennial, reached the national level; and, finally, those who were chosen as part of the Brazilian Representation in the XI Biennial will have an international audience.30

Although ostensibly concerned with selecting artists rather than assembling a ‘global panorama’ of Brazilian art, the Pre-Biennial was considered by some critics as the FBSP’s attempt to assemble a national salon. Paolo Maranca, the arts columnist for the Ultima Hora newspaper, was critical of the participation of young artists whose work was yet to mature, the majority of whom would never take part in the São Paulo Biennial.31 Geraldo Ferraz, who coordinated the Brazilian participation in the international biennial, defended this approach. He explained that the jury made their decisions on the basis of how likely it was that artists would produce important works in the future. This ‘immense’ task, he reasoned, was ‘a futurology – that is, the futurology of art criticism. For the Jury had to discover, in the names it chose, those whose “possibilities”, within a year, were such and sufficient to represent Brazil.’32 Of the artists previously mentioned, Pimentel’s work has reached international prominence following global revisions of the history of pop;33 Espíndola is known to a national audience; and de Souza is recognised regionally. The assimilation of these artists into the art circuit and the historiography of art thus highlights the role of the national biennial in changing conceptions of artistic value.

In his Ultima Hora column, Maranca compared the Pre-Biennial unfavourably to the long-established National Salon of Modern Art, which had been held at the Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ) since 1950.34 Whereas the Rio salon was regulated by the Brazilian Ministry of Education, São Paulo’s ‘new national salon’ was solely orchestrated by Matarazzo’s FBSP. The FBSP had greater freedom to act than the MAM-RJ, which was solely reliant on state funding, but it decided to replicate the Salon model, a fact that disappointed the critics. Frederico Morais, who had served that year as a jury member for two other national salons, was critical of how the exhibition was organised.35 In a review entitled ‘Pre-Biennial: A Pity’, Morais expressed his appreciation for the idea of a panorama of Brazilian art, but offered a clear verdict on the result: ‘the decisions and vacillations in its organisation, the failures of the regulations, the composition of the regional juries and, finally, the choice of the final jury, all worked against the exhibition. The result is more than melancholy. It is tragic.’36

The national politics of regional participation

The FBSP’s second national exhibition took place in 1972, with a new organisational structure. It took the form of two concurrent exhibitions ‘under the sponsorship of the Government of the State of São Paulo, Secretariat of Culture, Sports and Tourism, the supervision of Central Executive Committee of the 150th Anniversary of the Independence of Brazil, and the direction and organisation of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.’37 Although they shared a catalogue, the two exhibitions were distinct: Brazil, Plástica-72 was coordinated by Mário Wilches, General Secretary of the FBSP; the Exhibition for the 150th Anniversary of Independence, meanwhile, was organised by a member of the military, Major Vicente de Almeida.

As this title indicates, the 1972 exhibitions coincided with the 150-year anniversary of Brazil’s independence. The country’s celebrations, which included the inauguration of a new Copa Independência football tournament, appealed to a civic-nationalist imagination and offered a synthesis of the euphoria generated by the Brazilian Economic Miracle.38 The festivities began on 21 April (Tiradentes Day) with the I National Civic Meeting,39 and culminated in the ‘Week of the Fatherland’ in September, with the inauguration of the Independence Monument in São Paulo, containing the newly repatriated remains of Brazil’s first Emperor, Dom Pedro.40 Reliant on public funding and incorporated within nationwide independence celebrations, the 1972 edition of the national biennial established an explicit alignment between the interests of the FBSP and those of the authoritarian state. This was expressed by the language of its catalogue, which describes the exhibition as ‘an event of civic pride’,41 and in Matarazzo’s speech at the exhibition’s inauguration, where he proclaimed the exhibition to be ‘capable of awakening and effectively mobilising the artistic capacity of the country’.42 The Executive Committee of the independence festivities organised four regional shows to gather works for the two São Paulo exhibitions. Each involved independent art critics, but the titles of the exhibitions established a clear link to figures and events associated with the official independence celebrations.43

Brazil, Plástica 72 reflected an increasing interest – within the FBSP and among its advisers – in experimental currents of art in Brazil. Artists could apply by submitting works for selection processes carried out in São Paulo, Curitiba (Paraná), Florianópolis (Santa Caterina) and Goiânia (Goiás). The invited artists were placed into one of three sections: ‘Conceptual Art’; ‘Art and Technology’; and the less-defined category of ‘Environmental Art, Varied Propositions and Research’.44 The display aimed to reflect the country’s most current artistic concerns and included such artists as Lothar Charoux, a founding member of the São Paulo Concrete group of artists, Mario Cravo Neto, Espíndola, Carlos Fajardo, Frederico Nasser and Anna Bella Geiger.

Unlike the Pre-Biennial of 1970, the 1972 exhibitions were not primarily mechanisms for selecting artists to represent Brazil at the subsequent São Paulo Biennial. There was, however, a subtle clause in the regulations, which proposed that this national ‘experiment’ could play a part in defining criteria for the subsequent biennial (the twelfth São Paulo Biennial, 1973).45 This was most evident in the ‘Art and Communication’ section of the twelfth São Paulo Biennial, organised by Wilches and the philosopher Vilém Flusser, who had devised the thematic sections of Brazil, Plástica 72. The 1973 display included a large number of the artists that had shown in Plástica 72, and a distinctly regionally diverse range of Brazilian artists.

The regional contemporary

In preparation for the National Biennial 74, the FBSP’s external advisory group added the national exhibition to their formal agenda for the first time.46 Their first decision was that a figure linked to the field of art and culture, Olney Krüse, and not an official of the FBSP, should be responsible for liaising with the Brazilian states.47 The subsequent preparations for this edition reveal a more transparent and structured approach. The objective of the 1974 iteration was again to pre-select Brazilian artists for the subsequent international São Paulo Biennial and it was preceded by selections, in every Brazilian state, agreed by a single itinerant jury. The travelling jury selected 496 works by 155 artists. The works selected from each state were transported to São Paulo, where they were displayed in corresponding sections in the manner of national delegations at the São Paulo Biennial.

In line with the FBSP’s apparent drive for greater transparency, the National Biennial 74 catalogue included two texts that reflected on the process of organising and assembling the exhibition. In ‘Voyage to Brazil: State Participation’, Krüse describes his job not as one of selecting works but of building diplomatic relations with regional officials and cultural institutions – in other words, not to curate the exhibition but to ensure that it would happen.48 The text collectively authored by the jury, ‘For a Resonant Art’, emphasises the importance of capturing works that are characteristic and representative of each region, with no regard for technique, style or trend, and thus exceeding ‘São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro – read international – requirements’.49 The jury recount their ‘extensive travels’ across Brazil’s ‘multifaceted and practically unknown archipelago’, and note the contribution of local art critics, who helped them to ‘keep one reality in mind: every island that constitutes Brazil enjoys its own particularities’.50

The exhibition was conceived as a broad survey of the country’s art, which would encompass a range of practices, from popular arts to contemporary proposals. Prior to their trip, the jury agreed that their selection should not only consider ‘values such as contemporariness, expression or whatever it is that contemporary art can elicit’, but that ‘the expression of each Brazilian state would have to be resonant at the level of the community from which it emerged’.51 Rather than presenting works that aligned with the contemporary art practices dominant in Brazil’s urban centres, therefore, the exhibition sought to present a wider picture of contemporary Brazilian art by championing regional practices.

The biennial’s greatest honour, the Grande Prêmio, was awarded to Etsedron, an artist collective formed in Salvador, Bahia, in 1969. The group established themselves with a series of environments produced for exhibitions associated with the biennial, including the regional north-east Pre-Biennial (Recife) and São Paulo Pre-Biennial of 1970, and the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973).52 The researcher Walter Mariano describes the word Etsedron – ‘Nordeste’ (Northeast) written backwards – as both the group’s name and its manifesto.53 It functioned as a metaphor for the group’s drive to counter ‘the reality of the Northeast – and the country in general – as presented by the government and the economic elite’ at the time of Brazil’s Economic Miracle.54

Fig.4

Etsedron

Performance of Selvicoplastia Environmental Project Etsedron II – The Art Continues (Selvicoplastia Projeto Ambiental Etsedron II – Arte continua) 1974 at the National Biennial 74, São Paulo, 1974

Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo

Etsedron’s practice was based on ‘convivências’ (‘interactions’) with rural communities,55 which Mariano describes as a form of artistic investigation bordering on anthropology. Their work, closely connected to its regional site of production, encapsulates the parameters set out by the jury. Etsedron’s project for the national biennial of 1974, Selvicoplastia Environmental Project Etsedron II – The Art Continues (Selvicoplastia Projeto Ambiental Etsedron II – Arte continua), was produced over the course of six months in Itaituba, a town bordering the Amazon rainforest in the northern state of Pará. Its presentation in São Paulo included scarecrow-like figures made from low-cost, locally sourced material and was animated by dancers (fig.4). Matilde Matos, an art critic for the Jornal Bahia newspaper and member of Etsedron, reported that the group had chosen Pará ‘as we might have chosen Ceará, Piauí, Paraíba or Maranhão’, because they looked for places ‘that can give us the meaning of our land ... What interests us is Brazilian reality and the Amazon region is a cry, with the jungle, the Indian, the transamazonia itself’.56

Etsedron’s presentation at the thirteenth São Paulo Biennial (1975) involved the participation of the North American choreographer Clyde Morgan, a specialist in African dance who worked in Salvador as Artistic Director of the Grupo de Dança Contemporânea at the Universidade Federal da Bahia.57 This display elicited a debate concerning the presence of what Aracy Amaral named a ‘rural [sertaneja]’ art within ‘a Biennial modelled on Venice’.58 Amaral’s defence of Etsedron, coupled with her involvement in transcontinental debates concerning the nature and specificity of Latin American art, precipitated a wider discussion of the group’s work.59 For the art historian Isobel Whitelegg, Amaral ‘read Etsedron’s collective work as an alert addressed to the southern metropolis, not necessarily in drawing attention to the economically drained north, but in reminding the “country-continent” of its roots’.60 Amaral’s writings confirm that by deviating from metropolitan standards of presenting art, Etsedron launched an institutional challenge to a biennial based on the Venetian model.61

A biennial without refusals

The National Biennial 76 opened with the announcement that it was to be the last, and to the news that its selection jury had decided to accept every artist registered for the event.62 The jury addressed their collective decision in a catalogue text entitled ‘Biennial without Refusals’, which explained that their intention was to ‘offer the general public a view of what is made in the country’ by accepting submissions with ‘greater, smaller or even without artistic quality’.63 The jury’s justification was that ‘as information, as material for analysis’ the exhibition would serve as an indicator of ‘what should and needs to be done in the country for the benefit of the development of art, not only in the big urban centres but also in places far removed from them’.64

About 1,200 works by 330 artists from all over the country were exhibited.65 Under the title ‘End of Chapter’, the juror Tavares de Araújo used his Veja magazine column to compile the reactions of other art critics.66 These included such criticisms as ‘this mere agglomeration makes no sense’ (Roberto Pontual, Jornal do Brasil); and ‘the role of the jury is to guide the public, it has one main function: to select’ (Jacob Klintowitz, Jornal da Tarde).67 Araújo responded that although the jury could have carried out a ‘good traditional biennial with thirty artists’, he questioned whether ‘such a selection would have provided a more truthful sample of the cultural specificities of Brazil today’.68 Pontual was resolute in his criticism of the jury’s actions, however, insisting in a later article that ‘if indiscriminate acceptance is the model to be followed it also needs a method, a system, an interpretative inclination to guide the immense amorphous mass of material available’.69

Fig.5

Robert Evangelista

Nicá Uiícana 1976, installation view as part of a later collaboration with Regina Vater at Clocktower Gallery, New York, 1989

300 Amazonian gourds and bird feathers

Dimensions variable

However, the jury, together with the FBSP, did exercise some discrimination by including special exhibitions, inviting additional artists and awarding prizes. Among the prize-winning artists was Roberto Evangelista, an artist living in Manaus, Amazonas, who had never exhibited before as an artist. He showcased three works in the National Biennial 76 that were closely associated with his Amazonian home state: Mano-Maná 1976, Nicá Uiícana 1976 (fig.5) and Mater Dolorosa – In Memoriam I 1976 (collection of the artist), the latter a transparent acrylic cube containing the incinerated remains of trees placed on a large square of white sand. In his article in Jornal do Brasil, Pontual characterised Evangelista’s work as a ‘doubtful’ socio-ecological enquiry, typical of the ‘large grandiloquent participations’ one might see in a contemporary salon.70 After emerging through this controversially selection-free exhibition however, Evangelista went on to establish a significant and internationally prominent career.71

Fig.6

Rubem Valentim

Emblem: Poetic Logo of Afro-Brazilian Culture – n° 8 (Emblema logotipo poético de cultura Afro-Brasileira – n° 8) 1976

Acrylic on canvas

1010 x 750 mm

Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), São Paulo

The Grande Prêmio of the National Biennial 76 was awarded to Rubem Valentim, a self-taught artist whose work has recently been the subject of renewed international attention.72 Following his participation in six editions of the São Paulo Biennial, Valentim exhibited at National Biennial 76 as an invited artist.73 He began making work in the 1940s, and his paintings display a consistent interest in the popular traditions of north-east Brazil. This interest developed into an engagement with the visual language of the Afro-Brazilian religions Candomblé and Umbanda. At National Biennial 76, he presented twelve paintings collectively entitled Emblem: Poetic Logo of Afro-Brazilian Culture (Emblema: Logotipo Poético de Cultura Afro-Brasileira) (fig.6) and contributed a text to the exhibition’s catalogue. Connecting his ‘plastic-visual-signographic language’ to the ‘mestizo-animist-fetishist’ values of Afro-Brazilian culture, Valentim argued for a universal language with a Brazilian character – one that does not ignore the international influence of artistic trends, but incorporates the ‘non-verbal elements’ that he considered particular to Brazilian culture.74 Valentim appropriates the language of geometric abstraction to build complex compositions that redraw and reconfigure Afro-Atlantic symbols, emblems and references. He transforms artistic languages of European origin that dominated a large part of art production in Brazil in the 1950s and 1960s (geometric abstraction, constructivism, concretism) by combining their forms with drawings and diagrams that represent the orixás (human–spirit intermediaries) of Afro-Brazilian religions, such as Xangô’s double-headed axe, Oxóssi’s arrow and Ossaim’s shafts.75

Opposed to cultural colonialism, respectful of Brazil’s cultural foundations and engaged with the language of constructivist art, Valentim articulated an Afro-Amerindian north-eastern Brazilian iconography that resisted the caricature of regionalism and folklore. As such, he is perhaps the artist that best represents the ideals of São Paulo’s national biennial on the occasion of its final edition in 1976. An underlying aim of the initiative was to resolve contradictions between regional and international contemporary art, presenting a Brazilian art that encompassed the differences contained within a vast country. Nationalism was the guiding force of the civic-military regime, and one that it deployed to wield power over the national biennial of 1972. But this did not entirely dictate the aims or aftereffects of either Brasil Plastica 72 or the national biennial cycle as a whole, which saw the emergence of artists, including Etsedron and Evangelista, who may not otherwise have participated in the international São Paulo Biennial.

By 1976, the debates generated by this short-lived cycle of national biennials had reached no consensus, but the FBSP had facilitated a significant challenge to its own criteria of artistic value. The biennials demonstrate a commitment to revealing Brazil’s local traditions, regional inequalities and diverse cultural roots, drawing on discussions around national and regional modernism and the relationship between centre and periphery.

Renata de Oliveira Maia Zago is Professor of Art History at the Institute of Arts and Design and permanent professor and current coordinator of the postgraduate program in Arts, Culture and Languages at the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora.