Introduction

When Tate Exchange opened at Tate Modern in London in 2016 it was described by Tate as ‘an open experiment that seeks to explore the role of art in society … [inviting] international artists, contributors from different fields, the public, and over 65 Associate organisations, who work within and beyond the arts, to collaborate with Tate on creating participatory programmes, workshops, activities and debates’.1 Anna Cutler, Director of Learning and Research at Tate, has defined its purpose further as drawing together

a range of methods, offering a civic space for dialogue and a platform to test and trial new ideas and emergent thinking. It aims to explore the role art can play in society and the value that might have; it seeks to be relevant and attendant to current local, national and international concerns, as well as to connect the art and ideas held within the gallery with all those who take part.2

Located at Tate Modern across an entire floor of the Blavatnik Building, Tate Exchange was envisaged as a space where activities could be freely accessible to drop-in visitors, and that could be independent from the learning programmes of the rest of the museum. As an important part of its strategy, Tate Exchange invited public organisations and groups to apply to be ‘Associates’ and curate their own programmes within the space. This approach enabled organisations of wide-ranging scale and profile to create content and work with audiences in one of the world’s leading art museums. In doing so, Tate Exchange aimed to ‘give participants an opportunity to contribute ideas by providing a platform and new networks reaching the broader cultural sector and generating practices, products and processes that can make a difference to culture and to society more broadly.’3

The programmes presented by the Tate Exchange Associates have grown in complexity over the four years since the 2016 launch, with a wide range of activities taking place and enabling imaginative and energising ways in which the public could engage with the museum as participants, audiences and co-creators. The evaluation that followed the first year anticipated the tone with which the programmes have developed and been received subsequently: ‘Tate Exchange has been embraced enthusiastically by the public, has the ability to be agile and responsive, diverse in content and audience, surfacing areas of practice, concern and interest that are of relevance to Tate as a whole.’4

Fig.1

A community participant and a student working together at ‘Spread Your Wings’, part of the University of Westminster Associate programme ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May 2019

Photo: Creative Minds

The University of Westminster’s Associate programme was organised by the academic team teaching the MA in Museums, Galleries and Contemporary Culture, a team that includes the author of this paper.5 This postgraduate course is based on the principle that student learning is hugely enriched by gaining a first-hand understanding of the issues, challenges and opportunities facing museums and, where possible, taking part in ‘real world’ activities in a professional environment (fig.1).

This article looks at the way that we in the University of Westminster Associate group embraced the challenge to create a public programme for Tate Exchange that involved both museum visitors and the students undertaking the MA in Museums, Galleries and Contemporary Culture. It explores how we devised a strategy for participation and a set of operational models that the programme could follow and adapt over a three-year period. It shows the way in which we used action research methodology to examine how our projects could provide multi-level engagement for visitors and contribute to the MA students’ learning. The programme emphasised that Tate Exchange is important as an experimental space that enables the museum to find different ways to engage with diverse audiences and communities. As a result, evaluation is an important component of projects of this nature, and this paper shows how evaluation methods were evolved as the programme developed over the three years.

Trust and values: An Associate’s perspective

Before moving on to discuss the University of Westminster programme in detail, it is worth highlighting here the wider context in which Tate Exchange operates. Creating opportunities for public engagement is not the only important and innovative role played by Tate Exchange: it can also be seen as an experiment in trust relationships. Trust can be seen in the manner in which Tate invites a wide range of partners to design and deliver activities within the space to support and articulate the core values at the heart of Tate Exchange: trust, generosity, risk, respect and openness.6 Trust also operates in the goodwill invested by the partners in working with the museum, and it exists on the part of the visitors who may be coming into a space that is unlike anything else they expect to experience in the building. However, there is also a broader context for this trust: museums operate within a trust relationship with society because they are deemed to provide an important cultural service that not only preserves and nurtures creativity, knowledge and heritage, but that also stimulates and offers spaces for debate, expression and inclusion.7 Tate Exchange and the programmes of its Associates bring this into sharp relief.

Initiatives like Tate Exchange illustrate that the trust relationship that museums have with society increasingly requires them to be open as opposed to restrictive, adventurous as opposed to conservative, and proactive as opposed to passive. This initiative is not only a national concern and it needs to be seen in a wider context. A debate at the International Council of Museums (ICOM) conference in 2019 epitomised this change in the understanding of the role museums play as part of society, when a new definition was proposed for the term ‘museum’.8 This new definition acknowledged the functional and traditional roles that museums have played but also suggested that they are places of engagement, agents for change, and have a responsibility to address political or social issues of both local and global interest.

The debate around the new definition of a museum was not resolved at the ICOM conference but the reverberations of the discussion were widely felt. This is the context in which initiatives like Tate Exchange operate and it highlights how a ‘values-based’ approach can be seen as an expression of this change across the cultural sector. A generation of museum professionals, enthusiasts and critical observers have addressed the need for museums to engage more directly and openly with the public and specifically investigate the needs of their visitors and non-visitors, to be polyvocal, inclusive and brave. In the UK, documents such as the government Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s Mendoza Review,9 the Museums Association’s Museums Change Lives10 and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation Our Museum reports11 have all pointed the way towards a deeper and more sustained understanding of social relationships and emphasised the need for institutions to open themselves to engagement with the public – not just as passive recipients but as participants, protagonists and content creators.

We can therefore see that Tate Exchange sits in the middle of a complex set of contexts, both local and global, and that the Associates and the programmes they create are instrumental in bridging the theoretical and the actual. The Associates’ programmes are part of a new generation of interaction between museums and the public seen at the granular level and they contribute to a critical mass of socially engaged museum practices.

University of Westminster’s programme

Fig.2

A student designing the space layout for ‘Waterloo Lives’, part of ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May 2019

Photo: Peter Ride

Fig.3

A student setting up an activity for ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May 2019

Photos: Peter Ride

As mentioned, the University of Westminster’s Associate programme was organised by the academic team teaching the MA in Museums, Galleries and Contemporary Culture. This postgraduate course is based on the principle that student learning is hugely enriched by experiencing first-hand the issues, challenges and opportunities facing museums and, where possible, taking part in ‘real life’ activities in a professional context. From this perspective, working on a project like Tate Exchange provides a fundamental and distinctly different form of learning to the theoretical education students typically receive on university courses in this field. By taking part in the Tate Exchange programme, students can engage with the ‘affordances’ of the organisation in ways that were otherwise unavailable to them if they are only examining the outcomes of a project.12 The annual programme presented by the university was curated by the academic team, but each programme consisted of a number of discrete projects that were designed and delivered by groups of students (figs.2 and 3). The students made decisions that determined how their projects evolved and were responsible for the outcomes. They were also responsible for mapping out and evaluating their own learning activities, which required them to gain a professional outlook and gave them the skills required for ‘reflective learning’.13

The following quotations from those who took part in the University of Westminster programmes at Tate Exchange indicate the different ways that activities can create new levels of meaning for participants.

I was able to sit back for a minute and experience Tate Modern like I never had before. I was already familiar with the spaces and the artwork that we were asked to work with, but I had never thought of it with any of my senses other than my sight. I was probably unconsciously using my smell, hearing and touch senses but I had never stopped to think about it. It was interesting to sit around a table with people I did not know and the more we shared why we thought a smell was similar to an artwork the more we felt comfortable with each other.

Maria, Tate Exchange visitor, 2017

The experience helped to completely remove certain preconceptions about museum visitors as ‘predominantly passive’ in the museum experience. I now identify that every individual has the potential to generate interesting conversations using their personal experiences regardless of their previous exposure to art or cultural products. [It was] enhancing the idea of a museum as a place for meaningful experiences and not as a ‘three-dimensional art history lesson’.

Milo, student organiser, 2018

Amazing. A wonderful time. I’ll come again.

Christine, Tate Exchange visitor (aged 102), 2019

Fig.4

Participants deciding on moral and whimsical choices in ‘Make Your Decision’, part of ‘Make or Break’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, March – April 2018

Photo: Peter Ride

Fig.5

A Tate Exchange participant receiving a ‘secret message’ from ‘The Globe’, part of ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May 2019

Photo: Peter Ride

Each of the university’s programmes was designed around a theme set annually by Tate Exchange, and provided an umbrella concept and a provocation. The first programme, titled ‘Tasty and Smelly’ and held in 2017, responded to the theme of ‘exchange’ and consisted of multisensory activities that aimed to stimulate dialogue between visitors and trigger associations with personal memories. The second, titled ‘Make or Break’ and held in 2018, responded to the theme of ‘production’ and involved visitors creating some objects, destroying others and playing with the concept of being a ‘maker’ (fig.4). The third, in 2019, was ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’ and featured activities that explored the metaphor of ‘movement’, which was the Tate Exchange theme for that year (fig.5).

These three programmes had two principles in common: first, that creativity was at the heart of all the projects; and second, that the activities were designed to enable interaction, sharing and co-creation between participants. One outcome of the programmes was that they resulted in visual evidence of activity in creative environments. But a more important outcome was one that was not visible: the small transformative moments, or even just small moments of pleasure, that took place within and among the participants.

Applying action research methodology

As academic organisers, our goal in taking part in Tate Exchange was to develop a relationship between the museum and the university that provided an innovative student learning experience and a knowledge exchange. Because of the wider social context and a commitment to the values of social engagement discussed earlier in this essay, our secondary goal was to see how our activities could enable diverse groups of people to have a deeper involvement in culture and creativity. The central aspiration of Tate Exchange, as expressed in its 2018 ‘Theory of Change’, is that art should make a difference to people’s lives.14 This lay at the core of our sense of purpose and has synergy with the University of Westminster’s historical mission to enable a wider group of people to access the social and cultural benefits of education.15

Framed by these twin goals, the programme had an ongoing research purpose that could operate over an extended period of time. Because of the experimental nature of the project, we recognised that we required a research framework through which the outcomes could be followed and evaluated. The project was not overtly planned as a research investigation when the relationship between Tate Exchange and the university commenced, but the research agenda grew from the planning conversations, the emergent relationships and the questions that arose. Although participatory practice and co-design in museums have generated a considerable amount of literature during the decade prior to our project, we could not find existing models that combined student ‘workplace learning’ and museum-based socially engaged practice.16 As a result, we decided to use action research as a method, as it provided us with the freedom to be experimental and treat the structure and outcomes of what we were working on as emergent. This approach also enabled us to reflect upon how we were approaching the programme as it progressed, with points for review at the end of each annual iteration. Most importantly, it enabled us to develop models of participatory practice that we could follow and refine over the three years and further into the future.

Research in a creative environment like Tate Exchange required the kind of flexibility that action research methodology could offer because the action research process is dynamic, not static, and at no point are researchers separated from the activity that is taking place. Although action research is well established as a methodology within the arts and humanities, its critics often claim that it is not able to provide robust analysis because it is too imprecise.17 However, at the heart of action research is always a ‘real-world’ situation, where the scenario being addressed is an ongoing circumstance or problem that requires human intervention or action. Researchers using action research methodologies are therefore not impartial investigators, but are actors within the operation alongside the other participants, and have an investment in the ‘real-world’ outcomes of the activity. These can be studied over a period of time, in a cyclical fashion that involves planning, acting, observing and reflecting. Action research also recognises that research is unlikely to be hypothesis-driven but is frequently emergent. Consequently, research questions and concerns may arise and develop as the project progresses, as was the case in our work.

As organisers, we in the academic team deduced that this methodology would also be useful in the context of Tate Exchange because, typically, action researchers manage and control the variables that affect how people interact with each other and go about their work. By taking an action research-based approach we were able to separate the ‘known objectives’ from the ‘unknown’ ones. The known objectives were to do with student learning, public engagement and the management of the programme.18 The unknown objectives were those that we anticipated might arise within each year’s programme but were affected by factors beyond our control, such as audience attendance, the changing needs of community organisations we worked with, or the requirements of operating in the dynamic environment of the museum with its own organisational pressures.

Evaluating the programme

We employed two approaches to evaluate our project: student evaluation of the programme, and visitor evaluation that centred on qualitative methods. Our use of action research had a direct impact on our approach to the first form – the student evaluation – as an essential aspect of gauging whether or not we were addressing and meeting our goals. Two elements of this are particularly noteworthy: the students’ self-reflection on their role as participants and qualitative research into the engagement of public participants. Reflective learning was an important part of the student experience from the outset and over the three years we looked at different ways that students could self-reflect19 and self-appraise how their learning had arisen from designing and managing their programmes, working in teams, collaborating with external partners and interacting with the public.20 These points were often best expressed by the students themselves, as is shown in this quotation:

I was sceptical about our ability to deliver the project successfully… At some point, however, in the middle of the project when I was feeling stressed that things were not going well and we were running out of time, I reached the realisation that the point of the project was the process itself. Tate Exchange is a laboratory, and this was an experiment. Working on ‘Tasty and Smelly’ gave me the valuable experience of working on a ‘real’ project, helping to produce and deliver an event at one of the most prestigious public art galleries in the world. I was able to learn a lot, through the process of planning and executing the activity, and from observing more experienced colleagues.21

Fig.6

A visitor taking part in documentation with a Tate Exchange staff member, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, 2018

Photo: Peter Ride

The second form of evaluation that we used – visitor evaluation – took a qualitative approach to address how the public participants responded to our programmes, and the resulting data also fed into Tate Exchange’s annual programme reports (fig.6).22 This evaluation used a variety of methods including public feedback, participant observation and content analysis. In our first year, students looked in detail at who took part in the activities and the duration of their engagement, and gained feedback through interviews and questionnaires. However, as we self-evaluated as part of our action research cycle, we decided that this methodology was not in keeping with our intention to be creative and innovative in our approach. As a result, we decided it was more effective to take a ‘narrow and deep’ approach and concentrate on evaluating a limited number of activities in the programme, focusing on a small number of participants with whom we had developed relationships. This enabled us to gain a more complex and subtle understanding of public engagement and its benefits, and resulted in the development of ‘operational models’ that will be discussed below. This also simplified the ethics process, which operated at different levels of the project: the organisers were responsible for the ethics clearance for the overall programme with the university and Tate; the students gained clearance for work they did within each of the projects, which included consent from visitors.

As the second and third year progressed we explored a variety of qualitative research methods, including visitor observation and interviews, and focused on the learning outcomes of the public participants’ experiences. As we evaluated these methods in our action research cycles we decided that although they produced informative data, they still had too many limitations and were not flexible enough for us to get the complex feedback we wanted from the public about their experience. This in turn led us to question the form that this feedback might take, whether it be words on the page, the observation of activities, verbal information or the material evidence of things visitors made. As a consequence, we concluded that the next step in refining the evaluation methods for future programmes would be to incorporate content analysis. This method would be more in keeping with the goal of the programmes, and of Tate Exchange, to support and enable creativity. It could be used to examine the material that participants produce, using an approach similar to conversational analysis but drawing on visual outcomes rather than language and text. Although this would not provide a basis for comparison across activities, it could present a wider view of the connections that people make between activities in Tate Exchange and their personal lives, memories and external reference points, as well as society and politics. This could prove to be particularly pertinent when combined with other qualitative methods including participant observation, and could help identify what participants experience when having a sustained engagement with a creative project.

Operational models for participation

The most important outcome of the iterative action research cycles that we undertook was the development of what we have termed ‘operational models for participation’. These provided us with conceptual structures that we could work with and reflect upon, and applying the operational models became increasingly important to us as we developed our approach over the three-year programme. It gave us structures to refer to that were consistent even though they could be reinterpreted as our needs changed, opportunities arose and our appetite for new challenges increased. These were developed over the three-year period into two distinct models: a ‘three-ring model of activities’ and ‘triangles of participation and engagement’.

Before discussing these two operational models in detail, it is important to explain how they came about. The first iterative cycle of the action research commenced with a preliminary stage in the form of a series of workshops. In these we came up with ideas for how we might organise a programme, reflected on students’ own experience as visitors to art museums, and called on experienced curators and graduates to act as mentors. We also addressed the existing theoretical models for participation projects, who our key audiences and users were, and how we wanted to construct opportunities for engagement with a clear ‘invitation to participate’.23 However, as mentioned previously, the established models for participation projects in museums and arts organisations did not cover the mixture of professional learning and public engagement that was specific to our situation, nor did they easily relate to the perspective of Associates who were taking part in a museum programme like that of Tate Exchange. As a result, we recognised that developing our own theoretical models would be an important part of the way we could address our two research goals.

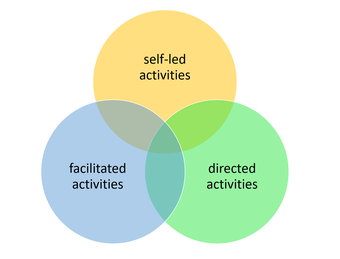

The three-ring model of activities

Fig.7

The three-ring model of activities

Image: Peter Ride

The first operational model addressed the way that the design of activities could enable differing options for engagement and participation and could be ‘scaffolded’ to provide different levels of complexity (fig.7).24 This model was visualised using the well-established form of three interlocking circles, or Borromean rings, each representing a different form of activity. Using ‘visual thinking’ to develop simple graphics for our operational models became an important part of our strategy from the outset.25 Visualising our models helped inform how we communicated with the students about project design and to our partners about programme planning. It also provided a useful tool when we worked with the production teams at Tate and shared information about our experience with other Associates.

The upper ring in the three-ring model represents self-led activities, which were designed as activities that required no instruction and that visitors could simply take part in without interaction with student facilitators. An example of this would be a display board with material such as threads or paper where the purpose was clear from its presentation and the public would respond by writing notes, arranging items or creating designs (see fig.4). Another example would be a multi-sensory experience where visitors would simply handle or smell objects, listen to sounds, and make comments. These activities were open installations with no beginning or end so that participants could join in at any time. During our first year, we realised the importance of giving people time and space to explore for themselves without guidance. Using ‘self-led’ activities in Tate Exchange was an important part of our strategy because entering a space geared towards participation could be intimidating for some visitors and providing visual installations had an advantage because it offered a familiar form. We also recognised that our purpose was not to attempt to present stand-alone artworks since this was what visitors would see elsewhere in the museum galleries.

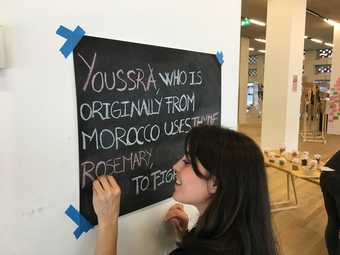

Fig.8

‘Spice Market’, part of ‘Tasty and Smelly’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, April 2017

Photo: Naheed Bilgrami

Our conclusion during the first iteration of the action research cycle was that self-led activities were essential as an ‘entry point’ for the public as they offered visual material for visitors to respond to. Therefore, all the ‘self-led’ activities required a very simple ‘invitation to participate’ that needed to be visual and appeal to the curiosity of the visitor. An example from ‘Tasty and Smelly’ in 2017 was the ‘Spice Market’, where the public could smell mounds of spices that were laid out as in a Middle Eastern bazaar (fig.8). A primary aim was to make people aware of their olfactory sense, which is often ignored in an art space, and to communicate with each other about their responses and, if they wished, to write these down on paper shopping bags suspended on a washing line above them. Student facilitators were on hand to prompt conversation, ask questions and assist if needed, but were not calling on people to take part. The spatial flow within Tate Exchange was designed such that this activity was directly in the sightline of the doorway and would not be missed, so that it set the tone for visitors before they moved on to other activities in the space that explored multisensory perception with greater complexity.

The lower left circle in the three-ring model represents facilitated activities, which were ones that participants could join at any time but where a student would lead the activity, explain or encourage. These activities often resulted in a visual output that would remain as an outcome for visitors to see even if they did not want to take part. We found that facilitated activities frequently created situations where conversations would emerge between visitors taking part and passers-by, and that as a result, newcomers were often encouraged to join in. The ‘invitation to participate’ with projects of this sort was therefore a combination of the visible activity, the encouragement of the facilitator and the example set by other participants.

Fig.9

Keychain produced by a participant at ‘More Than Words’, part of ‘Tasty and Smelly’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, April 2017

Photo: Peter Ride

One such activity that formed part of ‘Tasty and Smelly’ was ‘More Than Words’, in which visitors were encouraged to think about artworks in the permanent galleries in terms of touch, taste, smell and sound. Prompts for this activity included: ‘If this sculpture was a smell, what kind of smell might it be?’, ‘If the painting was a taste, what sensations would you have in your mouth?’ and ‘If it touched you, how would it feel against your skin?’. The participants then created multisensory ‘captions’ for the artworks consisting of vials of scent, items to taste and touchable material like fabric, leather and sandpaper, which they constructed into a keychain (fig.9). This activity required skilful facilitation because the concepts were often surprising to visitors, but once they understood, they wanted to explore in their own time and play with the ideas.

Fig.10

‘Make, Break, Remake’, part of ‘Make or Break’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, March – April 2018

Photo © Tate Photography

The third of the three rings represents directed activities, which were time-based, with a specific beginning and end, such as a workshop. Sometimes these left no visual output, although the activity was usually photographed. The invitation to the public to participate was therefore through a form of signage or verbal encouragement. Often these activities gave space for visitors to engage at a deep level and could involve discussion, but they could also be extremely playful. An example from ‘Make or Break’ in 2018 was a pass-the-parcel-style activity called ‘Make Break Remake’, where participants sat around a table and had a short period of time to make an object out of craft materials (fig.10). This object was then passed to another person who broke or modified it. It was then passed in a different direction to someone who rebuilt it following their own imagination; sixty seconds later it was being deconstructed again; the cycle continued. An activity like this required directing and enthusing, but soon participants found that they had skills which they shared. The activity often led off spontaneously into discussions about art practices that featured chance, destruction and assemblage or social and environmental practices of reclaiming, reconstructing and repurposing spaces or resources.

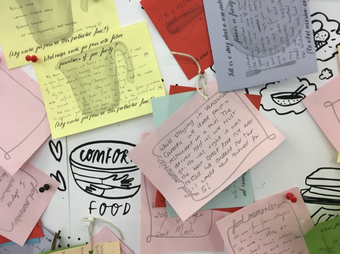

Fig.11

‘Food Memories’, part of ‘Tasty and Smelly’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, April 2017

Photo: Peter Ride

Fig.12

‘Food Memories’, part of ‘Tasty and Smelly’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, April 2017

Photo: Peter Ride

As we evaluated the public response to the programmes we found that some of the most successful activities were ones that were multipurpose and could be designed, or scaffolded, to provide many different forms of participation. For example, ‘Food Memories’, which was part of ‘Tasty and Smelly’, was a facilitated activity where visitors were able to sit down and discuss with students how food had played a part in their sense of identity, and how their preferences, recipes and attitudes might be inherited from family members, acquired through travel and expressed in different ways. The activity featured a large wall map of a fantasy ‘land of food memories’ and visitors could take multi-coloured prompt sheets and write down memories they recalled, favourite foods and anecdotes, then place them on the map (figs.11 and 12). When the student facilitators were not present, visitors could easily engage with the map on their own and leave their contributions. At other times there were organised workshops, co-hosted with the Migration Museum Project, where participants would bring in different food items and discuss the importance of food within narratives of migration. ‘Food Memories’ therefore covered all three forms in the three-ring model of activities: although designed as a facilitated activity, it could also be self-led or directed.

Through our analysis of the programme, we concluded that offering a combination of the three different forms of engagement was essential to meeting the interests and preferences of the visitors and that it also aligned with the way that informal learning can be constructed or scaffolded to provide different opportunities for participants. In addition, we concluded that scaffolded programmes of activity are desirable because they need not be seen as hierarchical; instead, visitors can recognise that they offer different forms of participation that can each be meaningful and rewarding.

Triangles of participation and engagement

The second operational model – triangles of participation and engagement – was used to identify the different levels of participation involved in the Tate Exchange programme. From the outset, we anticipated that engagement in participatory projects operated on at least three levels and that it would be important to be clear about the distinction between the different sorts of participants involved, who might range from collaborators and co-creators to casual visitors. Consequently, one of our aims through the action research cycle was to investigate how we could represent and test a model of participation and engagement that could identify the range of people involved with the activities by the nature of their engagement, and thereby anticipate their motivations and expectations. We also wished to see if their participation could be evolved over time so that individuals and groups could develop from being casual drop-in participants and become more involved as co-creators within the period of a single annual programme or across several years. We hoped that we could create scaffolded opportunities for people to be involved in the projects using methods that were similar to the way the ‘three-rings’ were scaffolded.

The museologist Nina Simon, in a key text addressing participation in museums, identifies four modes of participation: contributory, collaborative, co-creative and hosted.26 We initially based our planning on Simon’s approach, but we came to recognise through our action research process that our model had to include multiple and sometimes contradictory requirements. This is because our programmes were structured around student learning as well as public engagement, and involved a double level of collaboration between the university and Tate Exchange and between the students and community groups. Therefore, we adapted Simon’s design to propose a model of participation and engagement that could show how a successful programme featured a set of dynamic interrelationships.

As a result, we started our strategic planning by using pyramid-style visualisation that identified participation on three levels: the general public; collaborators and partners; and student creators. This presumed that there was a hierarchy to participation and that the more intensively people were involved in the process, the more meaningful their engagement would be. It also presumed that scaffolding would enable participants to move from one level to another. However, the analysis of the first and second years of our Tate Exchange programme taught us that while some of these points might be valid, they also provided a one-sided way of understanding how participation and engagement works.

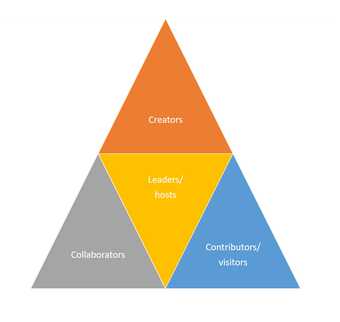

Fig.13

Triangles of participation and engagement

Image: Peter Ride

The revision to the model resulted in a different approach to thinking about the process of participation and engagement, one that was more focused on the relationships that were established than presuming a hierarchy. Using a segmented triangle with four compartments indicates how the different aspects of activity taking place had different purposes and different characteristics, but when interlocking together the four triangles represent a fifth, overall triangle: the unified experience (fig.13).

The upper triangle in the pyramid, ‘Creators’, represents participation by the co-creators and facilitators of the activities: the students and the volunteers. Fundamental to their position was that they had been given the responsibility to design and deliver a creative project and that they had been part of a creative dialogue with the institution. The motivation of this group to be involved has to do with personal identity – many of them were students who aspired to be museum professionals in the future – but also includes a commitment to working with socially engaged practices and helping make cultural organisations into more inclusive and polyvocal spaces.27 Therefore, they perceived that contributing to the programme, working in teams, being involved with Tate Exchange and forging links with new communities or organisations all contributed to their learning experience. They aimed to create activities that offered a deep and worthwhile public engagement, that gave them creative and intellectual satisfaction and that also enabled them to gain knowledge and expertise.

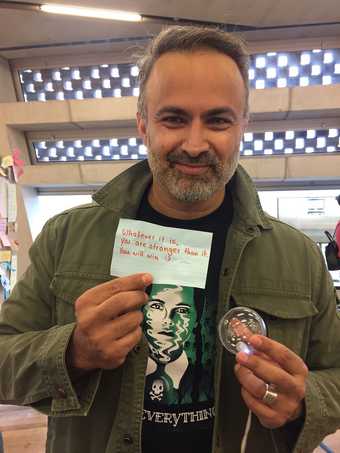

Fig.14

‘Make Me, Break Me, Read Me’, an activity designed as a game in which participants could leave a message in a balloon for an unknown person and receive one themselves, part of ‘Make or Break’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, March – April 2018

Photo: Peter Ride

The bottom right triangle in the pyramid, ‘Contributors/visitors’, represents the involvement of the general public. These could range from museum visitors with no previous experience of the season of activities at Tate Exchange, who might discover the space purely by accident and as such would have few specific expectations, to visitors who had come to Tate Exchange because of word of mouth, marketing or attendance at previous activities and who would have more concrete expectations (fig.14). Alternatively, they could be associated with external partners and therefore have other reasons for coming that related to their community connections or work and personal identities. We recognised that the engagement of many people in this category might be limited to the duration in which they were actually taking part in an activity, or even observing others doing so. Yet there would also be people whose intellectual or emotional engagement would extend beyond the time spent in the actual space of Tate Exchange, either because the activities resonated with them or because they were involved in dialogue that continued beyond the end of the activity.

The triangle on the bottom left, ‘Collaborators’, represents community partners, volunteers, stakeholders and external organisations. This includes groups who could have an extended relationship with the student organisers and who might be involved in the conceptual and practical development of the projects. We recognised from the outset that it would be desirable for us to develop long-term relationships with partners who had community interests and networks as this could ensure that the activities we offered reflected a diverse range of interests, not just those of the students. We also recognised, pragmatically, that while some of the Tate Exchange Associates might have constituent communities, members or friends that would provide an audience for their activities, the university students did not. Therefore, it was to the benefit of the programme if we could work with partners who would see that being involved might support their cultural aims. Discerning the motivation for these groups and individuals in participating was and is complex. It includes the cultural capital of being part of an activity at Tate Exchange, but a more important factor is the perceived benefit of the programme to their group’s wellbeing or in taking part in co-creating a stimulating and creative activity.

Working in collaboration with community partners meant that the students could have the opportunity to learn that co-creation and co-design might require them to negotiate with collaborators so that their activities might meet multiple objectives, and not just reflect their own vision. This could also expand the visitor base so that alongside the drop-in visitors to Tate Exchange we might have contributors with special interests and particular reasons for taking part. Participants in the ‘Collaborators’ triangle also included volunteers who were previous students on the Museums, Galleries and Contemporary Culture MA course and now worked in the cultural sector, and in some cases had been the student organisers of prior Tate Exchange programmes.

The central triangle in the pyramid, ‘Leaders/hosts’, represents the management-level members of the university team, including leadership and mentoring from experienced curators and graduates, and the involvement of the Tate Exchange curators and production team. While at times having an ‘arms-length’ distance from the design and delivery of the activities, both the Tate Exchange team and the university academics were imparting skills, training the students through leadership and pedagogy and setting targets and expectations, explicitly and implicitly. ‘Hosting’ is a fundamental concept because the viability of the programme depended on creating a structured environment in which the students, public and partners could interact, and a safe space in which they could take risks and be supported if they failed in their expectations. ‘Leaders/hosts’ also includes the overarching management overseeing finances, security, ethics and monitoring and evaluation, all of which were integral to the structure and balance of the programme.

Scaffolding the participation of collaborative partners

In order to explore how we could develop our relationships with participants so that their engagement could be scaffolded, we set out to form significant relationships with key partners from outside the university sector. In particular, we looked for organisations with whom we could develop sustained partnerships that could lead to shared projects over future years and that would enable us to do longitudinal research into the effects of taking part in the programme. As a result, three organisations became important partners in our activities in year three: Creative Minds, a UK-wide artist community; Core Arts, a not-for-profit social business based in North London; and the Bridge Project at Waterloo, a residents’ group local to Tate Modern.

Fig.15

Creative Minds participants taking part in ‘Dreamweaver’, one of the activities in ‘Make or Break’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, March – April 2018

Photo: Peter Ride

Fig.16

Creative Minds participants taking part in ‘Dreamweaver’, one of the activities in ‘Make or Break’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, March – April 2018

Photo: Peter Ride

The partnership we formed with Creative Minds illustrates how a strategic partnership can enable mutual and collaborative outcomes as well as a deeper and more sustained set of outcomes. Creative Minds is a social enterprise and nationwide community of artists who deliver art sessions to people of all ages in venues across the UK. They had been involved in our project ‘Make or Break’ in 2018, when they brought in groups from care homes to participate in ‘Dreamweaver’, an activity where visitors created compilations of fabric that adorned a hanging net (figs.15 and 16). The enthusiasm of the groups from the care homes was infectious, and very interesting interactions took place around reminiscence, craft skills and the thrill people felt at being at Tate Modern and making something personal that thousands of visitors could interact with.

Fig.17

‘Spread Your Wings’, part of ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May 2019

Photo: Peter Ride

Fig.18

‘Spread Your Wings’, part of ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May 2019

Photo: Peter Ride

The following year, for the programme ‘The Museum of Things that Don’t Stand Still’, the artist managers at Creative Minds worked with the students to define the concept of different activities for participants that again included those living in care homes.28 One of these was ‘Spread Your Wings’, which featured a tunnel of origami birds and flowers that grew over the week of its installation at Tate Exchange, and a peacock with a majestic tail to which visitors added painted feathers (figs.17 and 18). Students worked in the care homes alongside the Creative Minds artists-in-residence before the week at Tate Exchange so that the residents had a sustained involvement in the project. As explained by one of the student organisers, the planning represented a deep level of collaboration:

We wanted to develop a project reflective of the topic through physical, theoretical and metaphorical perspectives. Creative Minds reflected on birds’ movement, and how some residents can feel trapped by their disabilities. It was also quite a nostalgic experience for some clients. This metaphorical movement of stories implied is also a physical journey, enabled through the space. This path intended to become a materialisation of our biggest aim: share a creative moment and walk through it. What we desired from visitors was to share a moment relaxing, sharing and to give an opportunity to express their own creativity.29

Fig.19

Instagram post by Creative Minds about ‘Spread Your Wings’ at Tate Exchange, 18 May 2019

Image: Creative Minds

Image transcript: Thanks to all who joined us this week for our project at the @tateexchange in the Tate Modern, in collaboration with MA students from @universitywestminster. We’ve had the most incredible week! The project brought together a diverse range of people, young and old, to explore their creativity and add their own piece of art to our installation ‘The Museum of Things That Don’t Stand Still’. By the end of yesterday, you could walk down a colourful passage beautifully decorated with flowers and birds. Percy the grand peacock stood proud and tall with beautifully decorated feathers in his train. Our open wings sculpture looked vibrant…

The collaboration illustrates a symbiotic relationship on many levels. It enabled the students to develop a rich socially engaged project and gave Creative Minds the opportunity to expand their artistic practice into a context that they did not normally work in (fig.19). It set up the possibility that partners could create ‘spin-offs’ from the activities at Tate Exchange that they could develop for their own spaces. For example, the Bridge Project took inspiration from an activity co-created with the students and developed it further as part of the Waterloo Festival that they organised. Collaborations also provided both organisations with a track record and allowed them to form connections with individuals who might be able to contribute to later feedback exercises or research into attitudes into the long-term value of participating in arts events. Importantly for the purpose of our research, it also showed how we could deepen our knowledge of the benefits of participation through the programme and create richer relationships with external groups that enabled them to gain long-term benefit from Tate Exchange.

Conclusion

Museum educator Lisa Roberts describes the museum enterprise as being shaped by value and belief systems, observing that museums ‘give rise not only to the meanings constructed by visitors but also to those that are given by the museum. In a world that allows for multiple perspectives, the conditions for meaning have become as important as the meanings themselves.’30 The University of Westminster case study examined here shows how in a programme dedicated to public engagement and participation, the ‘conditions for meaning’ are not at all straightforward but instead reveal the varied priorities and needs of the different groups, organisations and individuals involved. The ‘operational models for participation’ that have been examined in this study show that ‘participation’ needs to be thought of as operating in many contexts and is not just limited to public activities.

Our programme demonstrates that in any participatory context, individuals or groups bring their context and motivations into the operation. The success of Tate Exchange, from our perspective, is that it creates benefit by bringing together a diverse range of groups and organisations with different points of view, all of which are committed to social engagement through the arts. Our twin goals were to provide a learning opportunity for the students on the MA course in a professional environment and to create programmes that were stimulating and rewarding for their public participants. Reflecting on these aims, we can conclude that by using the self-reflexive analysis of the action research method, we have been able to identify how the meaningful experiences that resulted from our programme apply equally to the students, the visitors, the collaborative partners and to us as the organisers. This has provided us with tools that we will use as we continue to develop our programme as a Tate Exchange Associate in future years.31

This case study also shows how the Tate Exchange Associates’ programmes can contribute to the ‘values-based’ approach of Tate and its goal to enable the public to make a meaningful connection between their experience in the art museum and their own lives. It reveals how participation can be designed to support inclusion and social engagement as well as the aspiration that art should make a difference to people’s lives. Most importantly, however, it shows that participatory programmes can result in small but important changes of perception, as expressed by one participant in 2017:

I reckon that the purpose of the activities was to open our eyes to a different view of the world of art. At some point, we’ve got to stop asking ourselves what is the meaning of everything – maybe it’s not so very important what it means. It’s probably more important what the sense of it is... They are two very basic and different things.

Bethany, Tate Exchange visitor, 2017