Introduction

This paper situates politically engaged artistic practice in the context of a critical and constructive encounter with socially engaged artistic practice, critical art and activist art. We argue that politically engaged practice, although influenced by these other forms, is also distinct and efficacious – a form of artistic practice capable of affective change and critique. We draw on debates from within art and political theory in order to gesture towards a form of practice that refuses roles and practices that support hierarchy, including ‘arbitrary expertise’, curation, ‘legitimate art’, privilege and cultural distinction. This has been developed in the concrete context of our own work together with galleries, schools, community groups and artists on the ‘margins’. Our practice has grown from our work at Tate Exchange: the gallery space and programme at Tate Modern, Tate Liverpool and online where social practice art is given primacy. Although most of our planning, devising, painting, building, workshopping and sometimes even exhibiting took place outside of Tate Exchange, the work led to a final intervention at Tate Modern. It is the Tate Exchange programme and its annual themes that have underpinned the development of our work. In response to the inherent tensions that exist in socially engaged art we have developed a prefigurative practice that is underpinned by a commitment to solidarity.

It is important to note from the start that we are political theorists and academics – not artists. Moreover, we are not museum and gallery studies scholars. That said, there have been useful and informative discussions in these fields on topics relating to the concerns of this paper.1 Our prime concern is with the operation of power within the political theories and artistic practices interrogated in this article. We have developed our practice in response to our research in radical politics, and this collaboration has included the development of theory alongside, and as part of, artistic practice.

Understanding Tate Exchange

Tate Exchange is a space of experimentation; it is heavily influenced by the groups of Associates who provide the content for the programme. Our Associate group – Canterbury Christ Church University – is one of these. This is not to dismiss the work and guidance of Tate Exchange staff who have played a large role in the direction of the programme and the work created. To do so would also be to dismiss one of the key tensions that this article seeks to explore: namely, the tension between the ‘expertise’ of Tate as an institution and the potential ‘illegitimacy’ of the artists and participants at Tate Exchange. Each group of Associates is given time in the Tate Exchange space as part of the programme, with some groups choosing to occupy it alone, and others, ourselves included, choosing to engage in collaborative practice with other Associate groups.

The place of socially engaged or community art in the art world is contested and fluctuating. For example, art historian Clare Bishop has described the tension between social and artistic discourses. For Bishop, the ‘social discourse’ argues on behalf of ethics and values while the ‘artistic discourse’ criticises the didactic nature of socially engaged art. Furthermore, the artistic discourse accuses socially based practices of removing any aesthetic, and therefore artistic, quality or merit from the work produced. This is a key framework for the development of our practice as it is something that we have observed throughout our time working as part of Tate Exchange. Many of the Associate groups are socially engaged artistic practitioners, or employ socially engaged practice as their method. This has led to this tension between artistic and social discourses coming to the fore in our evaluation of Tate Exchange specifically, and large international art institutions more broadly. It is this tension that creates the need for politically engaged artistic practice.

Our involvement with Tate Exchange has given us time to explore this tension and to model our practice, which is one based on prefiguration and an ethical commitment to the refusal of arbitrary ‘expertise’. We follow political theorists Paul Raekstad and Sofa Saio Gradin in their characterisation of prefiguration as: ‘the deliberate experimental implementation of desired future social relations and practices in the here-and-now’.2 Here we show a willingness to confront the political pressures and conflicts present in the space of Tate Exchange through what we term ‘progressive exclusions’, exclusions that are themselves a deliberate experimentation in desired social relations.

Each year Tate Exchange appoints a lead artist to open the programme and to work with the Associates to develop their work, if they collectively choose to do so. The lead artist for the third year of the programme in 2018–19 was Tania Bruguera, whose work has had a large influence on the development of our prefigurative practice and, we argue, on Tate Exchange and its relationship with the rest of Tate. Bruguera’s work directly challenges the tension between these discourses by foregrounding her ethical commitments and a ‘relocation’ of aesthetics to the creative process, as opposed to in the final object produced. We have found in her work and thought a number of practices that mirror our commitment to prefiguration.

Place

Fig.1

Tania Bruguera

Installation in the Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London 2018–19, as part of Bruguera’s commission 10,148,451

Photo: Tate

The sweeping entrance of the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern opens onto a major annual commission created specially for the gallery. Between October 2018 and February 2019 this was provided by Tania Bruguera in the form of a huge matte black square on the floor that bore an enlarged portrait of a Syrian migrant called Yousef – but only if enough visitors worked together to press and heat the material, revealing the image (fig.1). The efficacy of this depended on members of the public acting together – a number never revealed by the artist – and the temporary nature of the collaboration and quickly disappearing image underscored the ephemerality of the work. Deep, ominous sounds filled the cavernous space and in a small adjoining room, an organic compound was emitted that was designed to make visitors cry.

This set of works, collectively titled 10,148,451, formed only part of Bruguera’s contribution to the gallery during 2018–19. She also worked as the lead artist for Tate Exchange, and part of her project there included ‘re-imagining the institution’ itself by bringing local residents into Tate Modern, committing to a long-term project of solidarity called Our Neighbours.3 Visitors to the gallery are faced with a choice: do they go into the main galleries – renamed by Our Neighbours in honour of local community activist Natalie Bell – or do they walk through the former oil tanks from where they can ascend the new Blavatnik Building to the level reserved for Tate Exchange?

High on level five, overlooking the Shard skyscraper and the borough of Southwark, Tate Exchange has hosted over sixty Associate groups – of which we are one – that are involved in socially engaged practice, community art and open workshops. This is a space of play where the public are welcome to engage with a wide range of artists, community groups and institutions. We have been involved with Tate Exchange from the beginning and our experiences with it have led to this research. We have worked with a school in Dover, alongside partner Associates, and explored the relationship between politics and art. In our first year at Tate Exchange (2016–17) we were given the theme ‘exchange’ and our programme was entitled ‘Fairground’, based on the exchange of diverse populations in carnival, excess and play. We were part of a political carnival featuring stalls at which visitors were invited to test their strength and smash the patriarchy or ‘splat’ a villain of their own choosing, in a way that subverted popular fairground games. For year two (2017–18), responding to the theme ‘production’, our programme was called, simply, ‘Other’. This involved an in-depth examination of the intersection of class and gender in separate live art installations, including recreating bodily shapes by rearranging body parts on a mannequin and sitting on ‘boob-bags’ – beans bags decorated to look like breasts – in a feminist reading corner. In year three (2018–19) the theme was ‘movement’, and our project, inspired by the work of Bruguera, aimed to activate our politically engaged practice through a series of pop-up protests, political poster workshops and the creation of a user-generated political space. The title for this programme was ‘Movement²’ and the work forms the basis for this paper alongside our evaluation of current artistic practice and the challenges and criticisms of political practice. In year four (2019–20) the theme of ‘power’ has formed the basis for our programme, which, sadly, we have had to adapt to work within the restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic. This programme has been based on greater levels of community engagement and support through community arts partner Dover smART.

Expertise, hierarchy and curation

Our practice is concerned with challenging the hierarchical relations in which expertise in general, and categories such as ‘established art’ and ‘curation’ in particular, have been embedded.

Reflexivity is a central concern for any artist-activist/activist-artist who considers their practice to be non-hierarchical (or indeed, anti-hierarchical). Here we intend to refuse two interrelated narratives, each of which lack reflexivity. The first is a ‘hard’ narrative that considers that professionals – here we would include professional artists and art educators – have expertise that they can ‘transfer’ to communities in order to make the community’s life better.4 Such practice comes to the community from outside of it. In UK academia, for example, researchers, including those in the arts, are encouraged by government funders to ensure their expertly produced outputs have a meaningful impact on communities and wider society, often without considering whether communities and groups want to be impacted in this way. Such work may be socially concerned, but it is not socially engaged. The gaze of this approach is deeply problematic; it assumes that the lives of the ‘subaltern’5 would be better if members of these groups would accept the help of those who ‘know better’. The second narrative is a ‘softer’ one and is perhaps best captured in the idea(l) of ‘reflective practice’, which views uncertainty as a basis for reflective ‘knowing in practice’.6 Yet even here – despite what would seem to be a more radical and democratic approach – the structures of social hierarchy between practitioner and non-practitioner remain intact.

Within our artistic practice we have refused these hard and soft narratives, engaging in a range of practices that are themselves influenced by the nascent tensions in radical political traditions. For example, when working with our community partners, we are concerned first to respect the knowledge they have – a knowledge that is intimately tied to day-to-day practice, but which also embodies an ethics and a further (implicit or explicit) political world view. It is only then that we can expect our contribution to be both valued and valuable. Second, we never come to ‘help’; rather, we aim to work ‘with and alongside’. At least, these are our values. Third, we recognise the need to be constantly open to the possibility that we have got it wrong; to being called out by our partners if we impose our values, fail to respect their expertise or behave in a patronising way. The friendships that we have developed with Valleys Kids and Astor College over a four-year period from 2016 onwards, and our work with the Dover smART project since 2019, have been crucial here. Such friendships are necessarily founded on a basis of equality and the rejection of hierarchy.

We work as practitioners operating within and, paradoxically, outside of the ‘aesthetic regime’.7 We refuse the doctrinal division between theory and practice. Politically engaged artistic practice has attempted to navigate this division from within the institution itself. In Bruguera’s work with Our Neighbours she incorporated a process of critical reflection to address this. She facilitated a group that is created and sustained by its participants. In doing so she acknowledged the hierarchy involved while rejecting its basis in ‘legitimacy’ and attempted to abdicate her role as ‘expert’. She told Sharkey that she rejects ‘any specific powerful role’ and uses the practice developed with Our Neighbours to demonstrate the power they have to engage in the process of self-change. The atmosphere in the critical reflection meetings was described by Bruguera as ‘open’ and ‘inclusive’, despite there being animated debate and agonistic disagreement. In a discussion of conflict resolution and how problems were dealt with, Bruguera describes one participant who found this environment to be intimidating and who was therefore unable to participate fully. Despite feeling compelled to intervene, and thus accepting the role of ‘expert’ or ‘leader’, she allowed the group to solve this problem without direction. In this instance, the participants identified the need to include the individual, found a way to communicate in a less confrontational manner, and created a role for the individual that would allow them to participate fully. This increased the confidence of the participant to the point that they could take part in the discussions that had, previously, been a source of anxiety.8 This relatively small example demonstrates the way prefigurative practice, based in a critical awareness of the problem of ‘expertise’, can respond to doctrinal division.

Allowing participants the opportunity to find their role within groups brings about a substantive self-change, not to be mistaken for the aestheticisation of life. There is a danger that this process of aestheticisation can lead to the commodification of subjectivities, that is to their transformation merely into different lifestyles to be marketed to; take, for example, the ‘pink pound’ or the ‘Bic for Her’ pen. Instead it is important to maintain a critical stance in order to highlight the potential for the ‘aesthetic regime’ to operationalise and disguise the role of expertise in artistic practice. From within our own practice we have encountered the difficulties that this can cause. The artistic nature of our political project – as opposed to the political nature of our artistic work – has to some extent disguised the clear power imbalance that exists when we work with groups of young people. As a result, it can be difficult to maintain the critical stance required to assess the needs of the group; this can lead to the disguised re-creation of hierarchy. Ideas such as co-authorship and co-creation do not, by themselves, negate the soft narrative. Indeed, far from rejecting the existing social hierarchy, these ideas can exacerbate the power imbalances between participants and practitioners. While we hold Bruguera’s work in high regard as an example of political practice, it is still her name associated with these projects, not those of her participants/collaborators.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have argued that in contemporary informational society, arbitrary expertise, authority and even authorship are fundamentally eroded. Such autonomist thought has influenced many of the ideas in this paper. Hardt and Negri write of the ‘general intellect’, which is developed in Nick Dyer-Witheford’s idea of the cyber-proletariat – a new class of exploited and already subversive knowledge workers. For Hardt and Negri, we can understand the general intellect as the arena in which value-creating immaterial labour occurs. Hardt and Negri write: ‘General intellect is a collective, social intelligence created by accumulated knowledges, techniques and knowhow.’9 Thus, the socially creative aspect of general intellect places the production of knowledge outside of arbitrary hierarchy.10

In capitalist society, historical claims to know have been bound within a particular division of labour. These societies have attempted to remove ‘legitimate’ knowledge from workers and to deliver it into the hands of dominant classes. Such legitimation existed side by side with a process of ideological de-legitimation, perpetuated by dominant state structures and institutions – of which art institutions were to be an important part. Today we are presented with the possibilities of subversion on the basis of the sociality of contemporary labour forms. This is particularly the case with immaterial and affective forms of labour, key concerns of our artistic practice.

Here we might regard the labour of participants in Tate Exchange as having a dual character. First, as knowledge workers – to the degree that labour is potentially exploited on the basis of the neoliberal composition of the institution and that they contribute to the productivity of the ‘creative economy’.11 Second, as a site of the refusal of such exploitation – particularly to the extent that this refusal prefigures new, creative, non-hierarchical social possibilities.

It is important at this juncture to state a critical point. Hardt and Negri consider that the challenge of immaterial labour to hierarchy is ‘immanent’ (inherent). We consider that hierarchies are challenged mainly in the process of political practice: technological processes may shape these possibilities, but they do not as such determine them.

It is true that large institutions – at least as we have traditionally understood them – have come to be less necessary for information generation and dissemination, for a range of social and technological reasons; therefore, their legitimacy has undoubtedly undergone a crisis, as have those practices founded on such legitimacy.12 Yet as we find in our practice, any challenge to hierarchy will itself be met by challenges from the long-standing and consolidated hierarchies of institutions, practice and privilege. In short, actually-existing hierarchies remain more robust than writers such as Hardt and Negri suggest. Yet such hierarchies can be challenged, and therefore are worth being challenged. This brings us back to a key theme: curation, and its ideological-political function. Politically engaged artistic practice first challenges hierarchical forms of curation, to the extent that curation embodies forms of arbitrary expertise.

What became evident to us throughout our Tate Exchange experience was how curation often served to mask (and simultaneously to expose) deeply embedded hierarchical practices, including classed, gendered and racialised forms of what philosopher and sociologist Pierre Bourdieu termed ‘distinction’.13 All people may potentially be curators, but within the aesthetic regime it is difficult for them to assume such a function. Curation, for example, is a practice that serves to delimit legitimate art from illegitimate art, or more precisely, art from ‘non-art’ and consequently artists from ‘non-artists’. This is hardly surprising given the underrepresentation of working class people and people of colour in ‘expert’ curatorial roles specifically, and the artistic industries more widely – an underrepresentation that only intensifies as these stratifications intersect.14

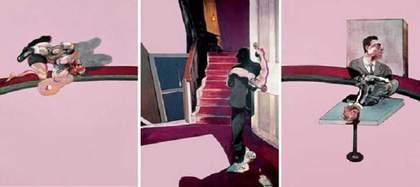

Fig.2

Francis Bacon

Triptych – In Memory of George Dyer 1971

Oil on canvas

Each: 1980 x 1475 mm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen

© The Estate of Francis Bacon/DACS 2008 Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

We can make a connection here with what sociologist Imogen Tyler has called ‘social abjection’.15 For example, museums are classed spaces, and ‘traditional’ gallery audiences do not expect their space to be contaminated by working class ‘waste’ – unless that waste is commodified in the collection. Francis Bacon’s work Triptych – In Memory of George Dyer 1971 (fig.2) is an interesting example here. In it, Bacon situates the classed object of his lover as simultaneously an object of love and one of disgust. But Bacon’s position as a highly marketable and far from working class artist means that the painting becomes more than an acceptable contamination: it becomes respectability, and importantly – in a final violence to its subject – it becomes money. This issue of social abjection is one we addressed directly in our work with Astor College, Dover and Valleys Kids, Rhondda Valley in collaboration with artist Kelly Green, as well as in planning year four of Tate Exchange, the theme of which was ‘power’.16

Such practices of exclusion may be more overtly pernicious than this, for ‘curation’ often polices the exclusion of such social waste. As self-identifying working-class artists, our legitimacy at Tate was frequently put on hold. Our participants at times reported that some members of the curatorial team within the gallery (not the Tate Exchange team) behaved in a way that made them feel unwelcome. Tate Exchange is itself located in such a way that the wonderful creative noise that it generates should not pollute or spill into the wider gallery space. It was very clear in practice what we knew at least in theory – that in a publicly funded art institution, socially engaged practice is afforded a much lower status than are the museum’s collections.

We are confronted here with a brutal illustration of the operation of power inside and outside the relationships that comprise our practice. The privilege that demarks an institution such as Tate allows it to be blind to these forms of power relation, for it ‘sets in place the limits of engagement from the outset’, as museums scholar Bernadette Lynch has observed more generally.17 But the example described above challenges this ‘blindness’, demonstrating to the participants the borders of their freedom within these ‘elite’ spaces and the power they hold, albeit temporarily.

Fig.3

Canterbury Christ Church University, People United and Valleys Kids

‘Movement²’ programme, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May 2019

Photo: Tate

In year three of Tate Exchange, our pop-up protest invited the public to suggest a cause for us to protest, and to join us in a celebratory and noisy procession around the Tate Exchange space (fig.3). One of these protests mobilised a call and response – ‘What is Art? This is Art!’ – to interrogate this issue. Even within community groups operating with a model of socially engaged artistic practice, the hierarchical operation of distinction was apparent. We found that the role of ‘curation’ was again crucial here.

Accordingly, we refuse the idea of curation, preferring instead a non-hierarchical model of co-creation. Political theorists Thomas Swann, Alex Pritchard and Ruth Kinna have identified the way in which anarchist-influenced movements, particularly Occupy (founded in 2011), ‘constitutionalise’ the consensus process.18 They have adapted their findings into a series of toolkits and guides on the facilitation of this process that is based in a commitment to prefiguring ‘post-sovereign’ politics through the constitution of ‘alternative sites of political agency’.19 Their work acts as a way of engaging participants in a reflection on their own political agency and exploring the inherent contradictions of consensus or supermajority as a basis for political action. This work has highlighted the way in which ‘bottom-up’ organising has finessed Swann, Pritchard and Kinna’s praxis, albeit imperfectly, emphasising that this is based on a rejection of the authoritative nature of legitimation.

In our view, such a process should develop to include two-way communication between teacher and taught.20 Operating within a hierarchy or an institutional setting can foreclose the possibility of two-way communication. The process of horizontal decision-making within the artistic process is one technique to refuse the co-option of artistic practice and to address the problems caused by the vertical decision-making structures of curation. Two-way communication is a defining characteristic of horizontal decision-making; to be considered ‘horizontal’ to any extent, decision-making processes must reject any procedure that forecloses the possibility of all participants contributing to the decision. This is an illustration of the tension within the limits of constituent and constituted power. Politically engaged artistic practice necessarily places priority on constituent power (that of participants or the demos). However, in order to maintain a productive relationship, the role of constituted power must be removed from the institution and be deployed within the practice.

An example of this within our own practice is our refusal of a final, single place of authority in the creative process and its delivery. In year three, participants were given space to explore their agency, both within Tate Exchange and within other networks in which they operated – for example, as members of a school. The consensus model was chosen by the participants as the best way for them to contribute and also to give them a way of refusing the power structures that reinforce their exploitation. This involved all participants meeting to explore an issue and the use of open discussion and a block or approval method that ensured total agreement or rejection of an idea. This has been broadly successful and the process-driven mode of operation has been held up by our participants as key to their continued engagement with us at Tate Exchange. During evaluation of our work on Movement², one of our participants, a teenage girl, commented that the consensus model gave them a new understanding of political interaction and a way of being listened to. While it may seem unsurprising that this model would afford the opportunity for members of the community to be heard, we had not anticipated the potential political impact this would have. This process of becoming is part of restructuring the symbolic order of the political to ‘democratise’ the role of the artist; or, to state it another way, it is through the freedom afforded in artistic practice that participants are able to address the imaginary relationship to society as a whole.21 Indeed, Antonio Gramsci’s claim that everyone is an intellectual has been echoed in artist Joseph Beuys’s provocation that ‘Every human being is an artist’ – a provocation that we embrace.22

Opening up these discussions has also generated productive forms of contradiction in our engagement with art institutions such as Tate. It could be argued that this has tested the ‘liberal sensibilities’ of such institutions, which, as we have already remarked, are sites of inclusion and exclusion.23 For example, how should an institution such as Tate engage in a conversation that seems to unsettle such liberal sensibilities? The tension between inclusion and exclusion is important here. We have placed a decolonising ethic and affectivity at the core of our practice and we are committed to a radical politics of inclusion. We agree with Tate Exchange’s wish to create a ‘place for all to play, create, reflect and question what art can mean to our everyday’.24

From socially engaged to politically engaged artistic practice

This section will cover how our critique of socially engaged practice has provided us with a basis for the expansion of our political practices. We shall also discuss political philosopher Chantal Mouffe’s conceptualisation of critical art and its relation to class politics, and Bruguera’s navigation of the tension between activism and ‘artivism’.

Our use of the term ‘politically engaged artistic practice’ is deliberate and considered. We agree with the claim that all art is political, though we appreciate Claire Bishop’s insistence that we need to understand precisely the ways in which such art is political.25 Put differently, it is not the case that all art is political in the same way. We might differentiate politically engaged artistic practice from the following: socially engaged artistic practice, activist art and critical art.

To start with socially engaged artistic practice, the Tate website describes this as follows: ‘Socially engaged practice, also referred to as social practice or socially engaged art, can include any art form which involves people and communities in debate, collaboration or social interaction. This can often be organised as the result of an outreach or education program, but many independent artists also use it within their work.’26 Socially engaged artistic practice in the UK emerged from a series of movements in the 1970s, but for many came to be subsumed within neoliberal politics in the 1990s. Art historian Julian Stallabrass has demonstrated the manner in which neoliberalism has ‘financialised’ what is supposedly an ‘exceptional economy’.27 He claims that the nature of the marketised, finance-driven logic of neoliberalism has subsumed both liberal consumerism and the operations of the art world. Stallabrass also argues that even those forms of artistic practice capable of resistance to neoliberal marketisation come to be co-opted, partly as a result of the way they are ‘generally reliant on private sponsorship and public funding’. As a result, artistic practice is ‘tied to corporate involvement in the arts and the commercialisation of the museum, in a way that directly cuts against its origins in do-it-yourself artists projects; this in turn is linked to the connection between globalisation and privatization (of which the art world is just a small part)’.28 Stephen Pritchard gives Park Fiction in Hamburg as an example of co-opted socially engaged art, writing: ‘Park Fiction was part of Hamburg city government’s broader regeneration agenda – an agenda that, like so many cities around the world, fetishised art, culture and commerce. It was, in fact, a testbed for a softer form state-backed cultural intervention that harnessed the social capital of activists.’29

Our practice

Key participants in our work have been young people from Dover in Kent and the Rhondda Valley in Wales, who we have worked with for over four years. We continue to work with and alongside Valleys Kids as we enter year five of programming at Tate Exchange (2020–1), where the theme is ‘love’.

Dover is an area that has suffered increasingly as a result of deindustrialisation, as is the case with many UK coastal towns, and it remains dominated by its port, creating a virtual liminal community: a space created for the purpose of passing through. Astor College is located in the Tower Hamlets area of Dover. This area is in the top 20% of the most deprived small geographical areas in the UK known as LSOAs (Lower-Layer Super Output Areas).30 We have developed our work within one specific community for the entire development of this practice. Similar to Bruguera, we believe that projects of this nature do not simply ‘finish’ when the project ends and funding stops. As discussed, socially and politically engaged practice can be counterproductive, especially when the long-term impact on participants is not considered. In our practice we have tried to reflect our commitment to not ‘abandon’ participants and communities.

Fig.4

Canterbury Christ Church University, People United, Valleys Kids, Whitstable Biennial and School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent

‘House of Horrors’, part of the ‘Fairground’ programme, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, April 2017

Photo: David Bates

In our first year at Tate Exchange we worked with live artist Kelly Green in our programme ‘Fairground’, an exploration of class identity through live art interventions. This work developed from workshops that Green devised for our participants. A number of live art installations were ‘worked’ by the young people that took the form of fairground stalls. These included a contemporary ‘freak-show’ called ‘House of Horrors’, where members of the public were invited into a dark box eerily illuminated by a spinning disco ball featuring fluorescent depictions of world leaders Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un (fig.4). A contemporary take on a fortune-teller – ‘Balloon Man’ – offered dark predictions for the future with balloons full of questions. Another stall, ‘Fish and Chips’, focused on common racial stereotypes of ‘white British’ subjects to challenge racial characterisations of them as ‘Little Englanders’.

Fig.5

Canterbury Christ Church University, People United, Valleys Kids and School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent

Feminist reading corner as part of the ‘Other’ programme, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern, London, May – June 2018

Photo: Tate

In our second year we continued to grow this project with Green and the final work was similar in form to the previous year. As mentioned above, the theme for the second year was ‘production’, and we developed this with Green to explore how ‘othering’ is produced. The content for this work explored how normative conditioning can produce oppositional binaries such as us/them, included/excluded and rich/poor. The live art component of this work focused on body image and objectification in response to our participants’ experiences of these phenomena. These included a feminist reading corner, composed of breast-shaped beanbags and literature produced by participants; a piece where members of the public were encouraged to construct the ‘perfect body’ on a pair of dressmaker’s mannequins; and a procession through the space that ruptured the usually quiet atmosphere of the gallery, featuring a refusal of social abjection (fig.5). We reflected on this work over two years and came to a number of conclusions that led to the development of the model and argument presented in this article. Most significantly, we decided to work directly with our participants on the development of the work. This allowed for direct access to data in the form of conversations with the young people and enabled us to be more flexible in our work. This way we could both learn from our participants and develop and test the theoretical underpinning of our practice.

The third year of our project built critically on what we had learnt from working with Tate Exchange over a two-year period. As outlined above, our programme Movement² took the form of a large installation mimicking the aesthetic of a political protest. This programme represented the culmination of three years’ practice and evaluation and we shall briefly sketch the methods here. The methodology we have proposed in this paper is grounded in a number of political and ethical commitments. The methods, perhaps better described as tactics, that we have employed are separate from the previous iterations of our programmes described above, however they cannot be separated from them. The long-term and embedded practice with which Bruguera engages is key to our approach and it is the trust and open relationships we have developed which acted to give us the ‘capital’ with these groups.

The work on Movement² began with a series of introductory workshops with the participants. These initially focused on exploring the previous work and the role of art in political movements and Tate Exchange itself. Participants were asked to produce art that responded to the general themes raised. This could be in any form and was used as a way of engaging the participants. The key focus here, as with all of our practice, was a rejection of objectification and a commitment to prefiguration.

The final ‘object’ – be it carnival protest, painting or impact report – can never be separated from the practice. However, the focus of our practice is on process, or what Bruguera describes as ‘production over implementation’.31 Our workshops led to the creation of objects, but their purpose was to reveal the power relations and hierarchies that operate within the group and with us as ‘instigators’. For example, the participants were allowed to break the usual rules for the space they were in: they could refuse to engage or could take control of the session.

We also held an open, free session at Tate Exchange alongside other political theorists, participatory artists, arts administrators and members of the public. In this session we explained the principles developed in our practice and encouraged an open discussion to produce provocations that were used to inform the work with our participants. This process was designed to critique and adapt the possible arbitrary expertise potentially present in our practice. For us, this was not intended to be merely an exercise in reflexivity – a thin, often problematic concept that can be used to excuse or to cover for the problematic employment of power. To this extent, we have tried to foster a critical relationship with the museum, heeding Bernadette Lynch’s warning that ‘the museum’s subtly coercive exercise of power ... [can] help to maintain the museum’s status quo rather than challenge it’.32

The second stage of the Movement² programme took place at the school in Dover where our participants were based. This involved the creation of the programme alongside the ‘objects’ that would be used at Tate Exchange. Consensus meetings were developed as a method and through these a number of political issues were established as key concerns for the group. However, the major development from this work was not these individual issues, but the process itself. Related directly to the prefigurative tactics employed, the participants took the decision to share in a process of open consensus discussion, a process that demonstrated the power that was already held in the group.

Following this, the group decided that they wanted visitors to be participants in their art. A large public square was created from artificial grass decorated with flowers and with workshop stations for the development of protest art and discussion. We took the decision to make the space a celebration and place of play, taking inspiration from a provocation produced during an early workshop: ‘joy can be an act of resistance’. Twice daily, members of the public were encouraged to join participants in developing a pop-up protest that would parade around the space. These meetings and protests formed the heart of the work based on research into post-sovereign forms of politics developed by Kinna, Pritchard and Swann.33 The protests also built on research by Bates, Matthew Ogilvie and Emma Pole on the Occupy movement and forms of constituent power,34 and their relation to the ‘Movement of the Squares’ (of which Occupy was a part) was both an aesthetic choice and one that gave primacy to forms of prefigurative politics that are commensurate with our practice. After gathering political grievances from the public, participants decided on the theme and the methods that the group would employ, which included creating chants and slogans that could then be used in the protest. The art-making and consensus process were the focus of the work and the procession gave an undefined ‘end’ that opened up the possibility of surprise: no editorial control was taken by the authors or other ‘experts’ in the space and this led to some unexpected results, including the contentious decision to protest the sugar tax – a measure introduced in the UK in 2018 to reduce the sugar content of soft drinks. The proposal was initially viewed as problematic, as the group broadly supported the reasons for the tax; however, this was debated and the speaker convinced the group it was an issue they should argue against since the impact of the taxation fell unfairly on younger members of society and those living on a low income.

How our practice responds critically to socially engaged practice

We have identified three challenges within socially engaged artistic practice that have caused us to move away from such a model. First, there is an important extent to which some socially engaged artistic practice comes to be reduced to a form of commodified and numerical ‘outreach’ that is at best anodyne and at worst complicit in mechanisms of domination and exploitation. For example, in order to justify their share of public revenue, large art institutions must demonstrate that they reach out to the public more widely – and in particular, that they engage with ‘marginalised’ groups. In itself, this appears progressive. However, outreach programmes are frequently judged through metrics based on ‘footfall’. High footfall becomes a necessary way of generating income. This brings these programmes within the totalising ‘rule of measure’ of the commodity form.35

Second, such footfall in itself does nothing to restructure galleries as spaces of inclusion. It is perfectly possible that new as opposed to traditional audiences remain segregated within gallery spaces, much as socially engaged art remains segregated from the museum’s collection. The architectural configuration of Tate Modern, and the location of Tate Exchange within it, is interesting in this regard. Tate Exchange is somewhat out of the way, situated on level five of the Blavatnik Building. As beautiful a space as it is, it is difficult to find for the uninitiated. The work that takes place in Tate Exchange is important and vital, yet given Tate Exchange’s location in the physical building and, one suspects, in the aesthetic hierarchy, it does little to disrupt Tate Modern as a space of exclusion, despite the hard work of the Tate Exchange team.

Our young people did their best to occupy Tate Exchange – a space with which many of them were not familiar. One young person stated: ‘I didn’t know the Tate existed. I didn’t know where it was. I didn’t know it was a thing.’ Encouragingly, another said: ‘It put us out in the world, with the museum being in London, it made us take that step.’36 As stated earlier, we also witnessed another side to Tate: a certain institutional silencing of our practice. In addition to the curators wishing to ‘contain’ the work, the institution withdrew permission for the work to move outside of the gallery spaces. This had the effect of refocusing the practice – anger and disappointment at the constraining of the participants’ practice turned to a productive discussion of how and why institutions choose to operate in the manner they do. This gave our participants a way of understanding the power relations within which the work operated, but also how they are viewed from within the ‘legitimate’ art world – even a part of it supposedly reserved for them. Initially this caused us concern and we asked if this might take away from the experience of the participants or create a sense of resignation that could have led to compromised or anodyne work. However, this illustration of the power structures our practice sought to address gave the work a clear focus and helped demarcate the axes of resistance. The work found a new, more internal focus that allowed for connection and collaboration with other Associate groups. The political nature of our work enabled what could have been perceived as a defeat to be used as a way to explore our position within the institution and highlight the social exclusion and objectification that had inspired the participants’ work.

The third issue for socially engaged artistic practice is that in order to become fully inclusive, it can shy away from asking ‘challenging’ questions; in this context, conflictual politics comes to be replaced by an ethics of anodyne consensus which reproduces the status quo. As Bishop rightly notes: ‘Unease, discomfort or frustration – along with fear, contradiction, exhilaration and absurdity – can be crucial to a work’s artistic impact’.37 Again, there is an interesting contradiction here. To be inclusive, we should not ‘unsettle’ participants. The privileged assumption is that marginalised, exploited and ‘non-traditional’ groups ought not to experience discomfort. This assumption may take two forms, one of which is reasonable, the other of which is pernicious. The first is a desire not to traumatise further those who may be genuinely vulnerable. (It is of course the case that the groups with which we work are likely to have been unsettled more in their life than most curators, given the demographics of the curatorial elite in places like the UK.) The second is to assume – implicitly or explicitly – that only those with a properly aesthetic habitus38 can adopt the ironic distance necessary not to internalise the unsettling gesture. To this extent, we consider that the gesture is itself depoliticised.39 Reflecting on our own practice, we have come to the conclusion that the desire not to unsettle says more about the privilege of curatorial elites and the way in which the funding of large art institutions is bound up with a regressive – and exploitative – status quo.

Critical art

It might be suggested that ‘critical art’, or art which has an acknowledged and explicit political content, has the opposite problem to socially engaged art: that is, it can be too didactic.40 Philosopher Jacques Rancière has argued against the (Marxist) variants of critical art that ‘see the signs of Capital behind everyday objects’ as aligning with didacticism – a line of critique with which Bishop is sympathetic.41 Critical art is perhaps closer to our practice than socially engaged art. Indeed, we would argue that Bishop mistakenly tends to consider that art with an explicitly ideological content is necessarily didactic.

Fig.6

The Yes Men

Exxon’s Climate-Victim Candles 2008

We will now turn to the theme of critical art in more detail. In a public debate at Tate Modern in 2019, Tania Bruguera and Chantal Mouffe embraced the label of ‘critical art’. To illustrate what she understands by critical art, Mouffe has referred to the example of the Yes Men. This group has intentionally parodied neoliberal ideology through work such as Exxon’s Climate-Victim Candles 2008 (fig.6). Posing as executives from the oil industry, they advised three hundred delegates at Canada’s largest oil conference that post-mortem humans should be used as a form of fuel ‘so the all-important free market could continue to work well past doomsday’.42

Mouffe’s notion of critical art is located within a post-Marxist politics that explicitly rejects practices of ideological unmasking and consciousness-raising as ‘essentialist’. This is connected to a wider rejection of Marxist class politics – indeed of all politics connected to class identity.43 This position emerged from Mouffe’s exposure to the thought of philosopher Louis Althusser in Paris in the 1960s – an engagement with which Rancière was also involved. Indeed, Mouffe’s critical art is in many ways aligned with Rancière. For example, Mouffe writes:

I do not see the relation between art and politics in terms of two separately constituted fields, art on the one side and politics on the other, between which a relation would need to be established. There is an aesthetic dimension in the political and there is a political dimension in art ... artistic practices play a role in the constitution and maintenance of a given symbolic order or in its challenging and this is why they necessarily have a political dimension. The political, for its part, concerns these symbolic ordering of social relations.44

Critical art for Mouffe is therefore an art that challenges the dominant hegemony. She states further that: ‘According to the agonistic approach, critical art is art that foments dissensus, that makes visible what the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate. It is constituted by a manifold of artistic practices aiming at giving a voice to all those which are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony.’45 It strikes us that there is much that is positive to be said about Mouffe’s vision of critical art – specifically the extent to which it comprises a significant gesture towards reasserting the importance of the political in the field of artistic practice. However, we do have some concerns. First, we are concerned that Mouffe’s work involves an a priori rejection of a politics linked to class identity. Mouffe seems to consider any such politics as constitutive of a form of classism, and therefore of a totalising essentialism. Yet to ignore questions of class identity is a political move that potentially silences voices at the abject margins of the neoliberal consensus. One does not have to regard the working class as the key agent of social transformation to consider that their narrative of exploitation can be subversive of capitalist hegemony and common sense. Connected to this, we are also concerned about a move present in the work of Bishop and Rancière which regards as didactic artistic practice that references and challenges forms of class marginalisation and exploitation. Here we want to stress how social class identity may be part of a radical art that moves beyond immediate dissensus, and points to a possible break with the existing state of affairs. However, it need not be. Indeed, the prefigurative practice supported in this paper simply seeks to mobilise dissensus, and in so doing signals towards a world better than this one – although in our practice we make no claims concerning what the content of such a world may be.

Our second concern about Mouffe’s vision of critical art is that it in fact gives too much respect to the status quo. It has been remarked that this was a problem with her earlier writings on radical democracy.46 Mouffe writes that:

Acknowledging the political dimension of such interventions supposes relinquishing the idea that to be political requires making a total break with the existing state of affairs in order to create something absolutely new. Today artists cannot pretend any more to constitute an avant-garde offering a radical critique, but this is not a reason to proclaim that their political role has ended.47

We do not wish to propose in any way a ‘brave new avant-garde’, to quote artist and writer Marc James Léger.48 Indeed, committed as we are to horizontalism, we must reject such an approach. Moreover, we are not proposing a total break with an existing state of affairs (though we do not rule out the possibility of such a break). Rather, we are gesturing towards the possibility of a prefigurative dissensus more radical than Mouffe’s politics allow. Hardt and Negri write: ‘Beyond the simple refusal, or as part of that refusal, we need to construct a new mode of life and above all a new community. This project leads not towards the naked life of homo tantum but towards homohomo, humanity squared, enriched by the collective intelligence and love of the community.’49 Our gesture is at once more radical than that of Mouffe, and less utopian than that of Hardt and Negri. Any orientation towards a ‘new mode of life’ is bound within our practice in the here and now, in a tactics of community life and of solidarity, an approach that denies any form of assumed hierarchical strategy.50

Activist art

This brings us to ‘activist art’. The name would suggest that this form of art is anything but anodyne. It is a term has become fashionable more recently, and Tate’s Art Terms describes it as follows, quoting Bruguera:

The aim of activist artists is to create art that is a form of political or social currency, actively addressing cultural power structures rather than representing them or simply describing them. In describing the art she makes, the activist artist Tania Bruguera said, ‘I don’t want art that points to a thing. I want art that is the thing’.

Activist art is about empowering individuals and communities and is generally situated in the public arena with artists working closely with a community to generate the art.51

We can identify at this stage three ways in which Bruguera’s work has been characterised – as ‘critical art’, as ‘activist art’ and (to use Bruguera’s preferred term) as ‘artivism’. We consider that her work also aligns with politically engaged artistic practice.

Bruguera prefers the moniker ‘artivist’ precisely because she does not feel comfortable with appropriating the label ‘activist’. Bruguera’s recent – and long-standing – protests and subsequent arrests at the hands of the Cuban authorities seem to contradict this. However, this reveals a certain operation of the aesthetic regime. Bruguera is engaging in what could be described as political activism, but she has been given the license of the Artist. As Rancière explains, in places of ‘high art’, artistic license leads to artists seeking ‘to give moral lessons or unveil the reality hidden beneath our social world’.52 Despite not always operating within a high art space, Bruguera’s practice is focused on the ‘unveiling’ that Rancière describes, a privilege accorded to her due to her status as artist. Other activists within Cuba have worked alongside Bruguera, or been involved in separate projects, however the aestheticisation of her political actions appears to preclude Bruguera from being labelled as an ‘activist’.

Towards a politically engaged practice

As we have argued above, socially engaged practice is a socio-artistic form that occupies a position of tension. Many socially engaged artists are concerned with co-producing art that seeks to transform in a substantive way the lives of those who participate in it. However, a great deal of socially engaged art is trapped within a pernicious neoliberal meta-discourse. This is a discourse in which all areas of life – including art/society, society/art – are subsumed within a logic of measurability and of the market. This discourse is so strong that it is almost impossible to imagine that another world is possible. As austerity policies in neoliberal economies result in the erosion of the welfare state’s capacity for love (rather than resulting in discipline), socially engaged art has necessarily filled a gap. In Britain and America, the socially engaged art of the 1980s confronted this tension head on. However, as marketisation seeped into more and more areas of civil society, the critical capacity of socially engaged art came to be challenged. It is increasingly – though not exclusively – the case that contemporary socially engaged art has been forced to underplay its critical role in order to gain the funding and legitimacy that enable it to perform those functions of loving and welfare previously performed by the social-democratic state.

Drawing on the work of cultural theorist Paola Merli, Bishop notes that such practices will not ‘change or even raise consciousness of the structural conditions of people’s daily existence’, thus offering us a view of what, for Bishop, marks the ‘success’ of such practices and hints at the disruption of the symbolic order required for this to be achieved.53 We are not arguing here that socially engaged artistic practice should be avoided or dismissed, for two reasons: first, because in a commodified neoliberal world where the state has been hollowed out, the function of such practice is often necessary; and second, because despite the best efforts of market fundamentalists, good socially engaged practice can still maintain a critical function. This critical function is more effective where socially engaged practice has developed out of the real activities of communities. For example, we have gained a great deal from working together with Valleys Kids. Their work has reactivated the historical sense of solidarity of working class communities of the Welsh Valleys, a sense of solidarity challenged – but not destroyed – by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s particular brand of neoliberalism in Britain during the 1980s. Fostering this sense of solidarity is a conscious move. Valleys Kids seeks to engage with often ‘discounted and undervalued’ communities, and to build affinities through their practice.54

We are seeking to formulate an artistic practice, or rather a range of practices, that is able to both balance its social commitments with its political presuppositions and address the potential foreclosure of the political from the communities and participants involved. Bishop’s statement above clearly creates a vision of success that is able to address the structural conditions of society, or at least ‘raise consciousness’ of them. Far from rejecting Bishop’s aims, we are proposing a category of artistic practice that embraces this challenge and engages in a critical and reflexive evaluation of its relationship with the state-market – including, as Stallabrass describes it, ‘Art Inc.’.55 Examples of politically engaged artistic practice can be found in existing artistic categorisations, as discussed above; however, our experience working with the artistic community as part of Tate Exchange has enabled us to develop the tools begin to define, or at least discuss critically and openly, the utility of political approaches to practice and the need for these to be theorised and explored.

Political approaches to artistic practice differentiate themselves from social-based approaches through their refusal of the commodity form, alongside a self-awareness of the internal relationship of the commodity form not only to the market but also to the state. Such practice draws on a range of theoretical tools and practices, informed by an engagement with critical theory’s interrogation of the commodity form, and Foucauldian and post-anarchist critiques of power.

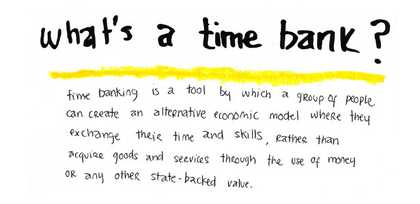

Fig.7a

Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle

Description of Time/Bank 2010

Image transcript: What’s a time bank? Time banking is a tool by which a group of people can create an alternative economic model where they exchange their time and skills, rather than acquire goods and services through the use of money or any other state-backed value.

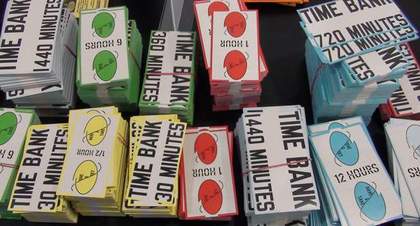

Fig.7b

Lawrence Weiner

Currency design for Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle, Time/Bank 2010

Photo: Julieta Aranda

In his 2010 book Dark Matter, artist and writer Gregory Sholette identifies a critical approach to ‘useful production’ taken by ‘non-artists’ and ‘illegitimate’ art forms that is able to resist the dominant market logic of the art world and forms the basis for a counter-history that is formulated ‘from below’.56 The history of art graduates, gallery technicians, amateur artists and other ‘non-artists’ who form the majority of the art industry, but who are excluded from its system of aesthetic valorisation, are identified as the ‘dark matter’ of the art world. Those who fill the galleries, serve its ‘customers’ and keep the art supply business in healthy profit drive, and are in turn exploited by the supply and demand economics that dominate the operation of this supposedly exceptional economy, are able to resist this capitalist prose – through a direct engagement with the political-economic hegemony. Examples such as Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle’s Time/Bank project 2010–ongoing, in which individuals exchange time and skills as opposed to ‘money or any other state-backed value’ (figs.7a and 7b), or prison artist Angelo’s Prisoners’ Inventions 2003–ongoing, demonstrate this critical relationship with market operation and a refusal of its logic.57

This is a key element of politically engaged artistic practice; however, it must be paired with other political critiques. Autonomous Marxism is important to our understanding of practice – for it is here that Marx meets Foucault.58 Also significant to our account of politically engaged practice is the Quaker-influenced direct democracy seen in the Americas, which had an impact on the global Occupy movement, and what sociologist Richard Day refers to as the ‘newest social movements’59 that have opened new axes of political resistance. It is not enough for such practice to refuse the commodity form; it is also necessary that such refusal occurs together, arm in arm, with others. Here we draw on the best work of the more critical forms of socially engaged practice, although our politics are more explicit.

Yet where such social movements have tended to regard an engagement with class politics as outdated and reductionist, we are concerned with creating an arena in which class-based practice can engage with a range of oppressions and thus build relations of solidarity that seek to challenge the status quo. This will include types of oppression that intersect with those of class – such as the oppression of women, the trans community, people of colour and people with disabilities. In such an arena, we can develop a fresh impetus towards forms of resistance, and the operation of power in the current political landscape.

Moving beyond Bishop’s critique of socially engaged artistic practice, our practice seeks to refuse the particular state-market conjuncture typical of neoliberal capitalism. We propose to do this through direct forms of artistic action, the establishment of relations of solidarity with a wide range of progressive struggles and, importantly, by developing prefigurative relations that point to the possibility of an alternative future. We are influenced by the history of working class movements, the feminist struggle, the practices of contemporary new social movements such as Occupy, and of those mutual aid groups that, for example, provided care and assistance in the aftermath of hurricane Sandy, which hit eight countries on the Atlantic in 2012. At their most effective, such practices challenged (and at times extinguished) the legitimacy of the state-market by proposing – in the words of Hardt and Negri – ‘active refusals’. Such refusals are active precisely because they embed forms of action that simultaneously expose the neoliberal state for what it is: a market guarantor with only a disciplinary function.60 Put another way, neoliberal states guarantee the separation of one individual from another; on the other hand, prefigurative and active refusals make claims that are founded on their solidarity.

Art and exclusion

Key to this refusal is the evaluation of activities outside of the direct context in which they operate. This is a feature of successful politically engaged artistic practice that also highlights its dismissal of plural liberalism’s emphasis on meritocracy: the claim that to exclude white men or mainstream artists from a creative space is a re-creation of the systems of domination and oppression that it seeks to eradicate. This is demonstrated to be erroneous through an engagement with the wider socio-political context, something that forms a key plank in politically engaged artistic practice.

Based in a shop in Queens in New York, Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International has, since 2011, formed a base for engagement in an ‘artist initiated socio-political movement’.61 Beginning with moderated conversations with artists and opening its doors for community use, from youth music tutoring to workshops on immigrant rights, Immigrant Movement International created a space of refusal for New York’s immigrant community. Although Bruguera’s work includes projects from other exploited communities and individuals, she has primarily focused on immigrant communities, which has led to Tate citing her work as a key example of ‘activist art’.62 Her work has included projects involving the Vatican and ones that address the yawning gap in the Cuban application of artistic freedom.63 She has faced arrest and imprisonment for her work as a result.

Bruguera’s 2018–19 Turbine Hall commission at Tate Modern saw her place a fifty-foot portrait of a Syrian migrant in the heart of a major UK art institution at a time when migration, especially from Syria, was the subject of much discussion. To talk of her work as ‘political’, then, seems wholly accurate. However, far from the direct addresses to the state-market seen in Pedro Reyes’s Doomocracy 2016,64 Aranda and Vidokle’s Time/Bank65 or Christoph Schingensief’s Please Love Austria 2000,66 Bruguera’s output offers us a glimpse of a practice that operates as a refusal of market logic, displays a critical awareness of its relationship to the state-market, and addresses the operation of power relations. Bruguera’s work eschews the traditional signification of Politics: she describes it as not ‘political in the sense of using an image that refers to a political movement or political leader, or political because it refers to a particular issue’.67

Fig.8

Immigrant Movement International demonstration, International Migrants Day, New York City, 18 December 2011

Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International engages in a progressive exclusion of people from outside the immigrant community (fig.8), just as her work with Our Neighbours is reserved exclusively for those with a geographical claim to membership, but both projects remain engaged with their broader context and the struggles that they seek to represent. Through these progressive exclusions and the critique of existing power relations, politically engaged artists and collectives are able to promote inclusion.

Immigrant Movement International identifies the need for support among the immigrant community in New York, a group of individuals who are suffering from the particular problems of arriving in a new place and being politically excluded through acts of othering. Bruguera is not making a claim to the primacy of this axis of struggle; she is identifying an area of reactionary exclusion and creating an act of progressive exclusion to negate it. She describes this process of socio-political evaluation as part of her body of work rejecting the neat, individual objects and projects usually associated with the art world, and her attempts to incorporate this within its wider political context: ‘I try to find success in things that are invisible, or are very long term. So it is very hard to see the whole thing.’68 For us, trying to see ‘the whole thing’ is a process of critically investigating the site of power and its systems of operation. Political philosopher Todd May states that the ‘political character of social space can be seen … in terms of intersections of power rather than emanations from a source’;69 this has become clear to us during our work at Tate Exchange in balancing the needs of both co-authorship and collaboration.

Exclusion and prefiguration

Working in collaboration with partner organisations who may not share one’s commitments, interests or values involves the direct exploration of the power relationships both in the social space and in its wider political context. This highlights to us the fallacy of the social space as existing a priori, as it is contingent on the intersections of power; relationships between institution, practitioners, participants and audience are what form the basis for Tate Exchange as much as they do Immigrant Movement International. This should not involve a dismissal of power, as that would concede to a unitary place of power, but the process must be predicated on an investigation into which relationships of power are acceptable and which are not. There are clear connections here to Sholette’s argument that artistic practice should reject market logic, only this is broader in scope.

The commitment to prefigurative practice underpins the ethical concerns and the ontological grounding of our work. Prefiguration is defined, in the broad sense, as the removal of the distinction between ends and means. In our own practice this influenced our decision to utilise basic consensus decision-making procedures at Tate Exchange. This refers to the process-based approach to artistic production and practice, as found in socially engaged practice, where the object is dismissed as the primary reason for engaging in artistic practice. We have seen that Bruguera argues for an art that ‘is the thing’, not an art that symbolises or re-presents ‘the thing’. She describes her approach as ‘implementation’, where a process-driven design requires a different decision-making process to object-based methods. This also replaces ends with means, but is premised on an art of becoming, which Bruguera describes as a practice that ‘opens up’ rather than forecloses. She gives the example of making a political t-shirt, explaining that the object-based nature of this work would lead to a closed set of artistic, political and ethical decisions, as ultimately the ‘end’ of the t-shirt is set. This is contrasted with an approach that ends with and is proven by the process that constitutes the practice. This, Bruguera suggests, is premised on the ‘transformation of the people’ as both its means and ends.70

Prefigurative approaches negate the meta-dialectic of the social and artistic discourses as described by Bishop.71 Bishop writes that the ‘social discourse accuses the artistic discourse of amorality and inefficiency’ and the ‘artistic discourse [accuses] the social discourse of remaining stubbornly attached to existing categories, and focusing on micropolitical gestures at the expense of sensuous immediacy’.72 This closely mirrors our own experience working at Tate. This tension was clearly represented in the interaction between our work on level five – and as part of Tate Exchange more broadly – and the curatorial stance presented to us by Tate. As discussed above, there was a curatorial disagreement on the nature of our practice and the limits that should be placed upon it, which in this case meant restricting the work to the physical space. Our work maintained its success through the commitment to prefiguration and the different set of decisions this presents. This is because the element of our practice affected by this tension was designed prefiguratively rather than being minimised by the tension – if the ‘end’ in mind had been the spectacle of protest outside of the Tate Exchange space, then this would have been catastrophic for our work. However, since we were primarily concerned with ‘means’, this allowed for the flexibility to alter the form and audience for the work without compromising its integrity. Reflecting on this process, one of the participants said that they ‘didn’t know that the Tate could be used as [a place for] such a political movement. The way we were able to use the space in the Tate to interact with the public and everyone could get involved, outside of the standard expectation of art.’ Here we can read the ‘standard expectation of art’ as the pressure of artistic discourse and it is interesting to note how the participant highlights their surprise that an art gallery can become a political space.

We consider prefiguration as an ontological condition for politically engaged artistic practice. This practice does not rely on an ontological foundation in human nature, nor does it propose any particular programme for politics or society. Rather, questioning the legitimacy of the existing power relations starts with the commitment to process and a refusal of the logic of the neoliberal market and state. In place of the often-quoted commandment to live as if we are already free, we propose that one should make art as if one were already an artist.

Conclusion

The need for an effective politically engaged artistic practice has never been more urgent. Neoliberalism is in crisis, a crisis which intensified after the financial crash of 2008. The ‘extreme centre’ can no longer hold.73 The subsequent revival of the politics of the far right in the US and Europe has posed a reactionary challenge to this consensus.

Our practice is progressively grounded. It seeks to refuse the marketised neoliberal agenda of society in general and contemporary art spaces in particular, while at the same time refusing the troubling rhetoric of the far right. Socially engaged art has done a great deal to work with those groups and communities who have suffered most from policies of economic austerity.

Our practice has facilitated the development of prefigurative spaces – grounded in an ethic of solidarity – where we can work together to produce work that is challenging, emboldening and, where necessary, disruptive. Our practice makes explicit the political within the artistic and the artistic within the political. It does not shy away from challenging problems, but neither does it propose a political programme as such. Rather, we work together with and alongside key stakeholders to co-produce art that reorients the lens through which we see the distribution of power in the world. In the words of one of our younger participants: ‘It’s not that I feel more grown up, but I feel that I am having conversations about things that matter, something that is bigger than myself.’