Over the past two decades, the field of exhibition history has shifted. From the formative ground established by key late 1990s publications,1 it is now both an established area of research, and a topic of interest for curators, publishers, museums and galleries. As a canon takes shape, so the case for deconstructing it grows.2 Recent contributions have drawn attention to the relationship between celebrated exhibitions and the infrastructural advantages they enjoyed,3 and between a show’s critical reception and its potential for historical recovery.4 Predictably enough, the São Paulo Biennial exhibitions that have best lent themselves to historicisation – notably including the twenty-fourth edition of 1998 – are those that enjoyed favourable material conditions and substantial critical attention in their time.5

For a biennial to make history, it seems, it must come with already existing ‘discursive density’:6 critical corroboration, well-kept records and locatable names. A biennial, however, is defined by both single editions and by its reiterative persistence in time. This complicates the task of producing any definitive history of this exhibitionary-institutional form. Linking together discrete moments at which individual biennials came to be recognised as models produces partial perspectives. This approach can elucidate a range of curatorial, critical or structural innovations to the biennial form, and convey broad historical narratives, such as how large-scale perennial exhibitions came to shape a global art world.7 A selective focus on these isolated moments, however, obscures the fact that it is also the nature of biennials to stumble, stutter and fail.8 The ‘mechanistic chronologism’ of a biennial does not only describe its ‘every-other-year‘ appearance.9 It also defines a specific institutional type, one that strains to keep pace, however conducive the circumstances, however likely the chances of critical success. To miss a beat for any reason short of force majeure signals institutional crisis. Tethered to this temporal rhythm, the biennial achieves a semblance of perpetuity while exaggerating its vulnerability to historical contingency.

The event at the centre of this essay is the twelfth São Paulo Biennial in 1973, which opened during a period of organisational instability, and almost four years into the technocratic-military regime of President Emílio Garrastazu Médici (October 1969 – March 1974). If a biennial’s potential to be remembered rests on positive interplay between institutional, structural and infrastructural forces, where does this leave this edition, born from institutional complications into the least amenable conditions for critical reception and historical recall?

The twelfth São Paulo Biennial was no model; it was an embattled event lacking unifying coherence. But there is historical significance to be retrieved from the discordant pieces of a broken biennial. To deploy Bruno Latour’s notion of the black box,10 just as an efficiently running machine will show input and output but conceal its inner workings, so the hidden complexities of a biennial exhibition are made invisible by success. The use of a central theme or innovative curatorial approach, as Bruce Altshuler has noted,11 can serve to hold an exhibition together, as if it were a unified artwork or a univocal statement. Conversely, in the absence of any guiding framework, the plurality of narratives contained within the whole become all the more apparent.

The twelfth São Paulo Biennial did not function as a cohesive ‘unit of artistic significance’,12 thus the exhibition in itself could not guide my historical analysis. Taking place during a messy phase of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo’s (FBSP) turn towards a thematic approach, and at a time of self-censorship and government surveillance, neither the exhibition’s curatorial apparatus nor its organising institution explains how this event related to its time. From its fragmented records, however, it is possible to reassemble a more nuanced articulation of context: a specific moment during the complex and changeable period between 1964 and 1985 that Brazil was subject to military dictatorship.

The twelfth São Paulo Biennial’s scant records contain clues to many stories, including that of a rogue British contingent.13 But my focus in this essay is the collective and critical works by Brazilian artists that were admitted to this edition on the basis of proposals. This unprecedented form of participation was the warped output of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo’s stuttering organisational reformation. I will first track the institutional compromises that produced the event of the twelfth São Paulo Biennial – between risk and self-censorship, theme and nation, the demands of artistic practice and the need for government support. I will then turn to the collective projects, reassembling some of those that remain overlooked or misunderstood, and restoring their associations with the concerns of their time.

São Paulo, 5 October – 2 December 1973

Towards the back of the twelfth São Paulo Biennial’s catalogue, written proposals for works of art are published under the heading ‘Art and Communication’. Participants within this section are listed by nation. Canada, France, Germany, Switzerland and the United States are each represented by one project, but Brazilian participants form a decisive majority. Several among them, including Ana Maria Maiolino and Terezinha Soares,14 have contributed individual proposals, but the longest are those that were collectively authored. One, entitled ‘Urban Anthropophoria’ (Antropoforia Urbana) descends after two lines of description into a poem:15

The theme of the proposal is dedicated to the man dismembered

divided

shattered

vertebral column where

feet / legs / trunk / hands / arms / eyes / ears

heads

try to compose

incomposables

a human being

decomposed

in body and in ideas that

the city

germ (shell and egg) of the man

the age

the community

the false ideals

grind

loose parts of a body in search of a truth

loose parts of a one-day body

and ideas

and ideals

that fell apart

but that survive

like man

like ideas

like ideals

as long as there is a poet

(though sad).16

Among the twelve participants listed for ‘Urban Anthropophoria’ are the artists Mauricio Fridman and Gerty Saruê and the concrete poet Augusto de Campos.17 But not every name is so easy to place. Many of those who are listed as collective participants within the Art and Communication section were then at the start of a short-lived artistic career, or else not linked to the professional art sphere at all. These names therefore fall outside established frames of art historical reference. Similarly, the dissent expressed by certain collective proposals exceeds existing understandings of what artists could say or do within the São Paulo Biennial at that time.

The 1969 call for an international boycott of the São Paulo Biennial, an event addressed by Caroline Schroeder elsewhere in this issue,18 casts the biennial as both an instrument of the regime and a space where freedom of expression was impossible (a tactic necessary to its success). The boycott has become a widely referenced event, and one used to structure anglophone studies of Brazilian art under dictatorship.19 Thus the strategic narrative it deployed has endured: that critical participation was unthinkable, or that any form of political dissent or social critique was by necessity more subtle. Contrary to this, several of the proposals published within the twelfth São Paulo Biennial’s catalogue cut to the heart of Medici regime by targeting its key strategy: pursuing economic expansion at the expense of disenfranchisement and environmental destruction.

A proposal from the city of Londrina, Paraná, entitled ‘Anthropomagic Village in the Land of the Red Feet’ (Aldeia Antropomágica na Terra das Pês Vermelhos) asserts that ‘in a region where economic groups control most of the profits obtained from arable farming, the majority of the population that does this work is left aside’.16 In ‘Objective Project’ (Projeto Objetivo), a group from Curitiba propose an analysis of the detrimental effects of the city’s urban and industrial expansion.20 Another contribution, ‘Santa Caterina Project’ (Projeto Santa Catarina), addresses the colonisation of indigenous territories:

The vain euphoria of ‘technological age’ man is a hypocritical formulation of ethnocentric prejudice. The curiosity of the ‘civilised’ citizen in the face of primitive societies is the contempt of the colonialist dressed up in composure. The native variant of this prejudice is integrationism. Its practice is implicit in the destruction of indigenous societies and the assimilation of their destruction by the uniformity of ‘industrial civilisation’.21

Little appears to have been said, at the time and on record, about these proposals or the realised projects they point to. The archives of the São Paulo Biennial have adapted their structure over time to make it easier to find names associated with collective projects.22 But the folders are thin, and the FBSP’s public narrative on the 1973 edition does not mention the proposals.23 It tells us instead that the biennial is remembered for an unprecedented exhibition of the work of Kandinsky, and the participatory and playful nature of the contemporary works on display.

Fig.1

Caricature of contemporary works shown at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973), illustrating Carlos Eduardo Novaes Wilmar’s article ‘O vale-tudo da arte’ (the anything goes of art), Jornal do Brasil, 11 November 1973

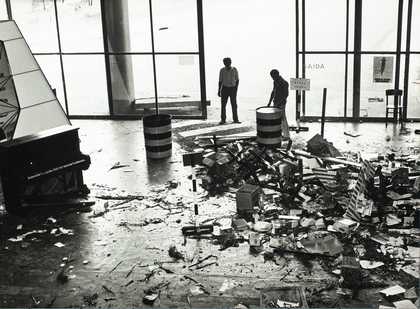

Fig.2

Twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973), view of ground floor showing works by Vera de Figueiredo and Ivens Machado

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo/Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo

Such playfulness was illustrated by one of the Art and Communication section’s most photographed works, the participatory installation Enter Hell and meet yourself (Visite o inferno e encontre você) by the Rio-based film-maker Vera de Figueredo.24 From the dark cavity of a velvet-lipped mouth, an actor’s voice called visitors to climb inside, via the tongue, where they were confronted with their own reflection. Press photographs of children queuing to clamber inside Figueredo’s gigantic mouth supported the notion that this was a biennial that looked like a funfair, fuelling the ire of critics writing under headlines including ‘The biennial of what? why? with who? for whom?’; ‘White and empty: is this communication?’; and ‘Testimonies of the absurd’, and – for an article illustrated by a caricature of the contemporary works on display – ‘The anything goes of art’ (fig.1);25 A photograph held by the biennial’s archives (fig.2), however, depicts the close proximity between Figueredo’s work and another that could not be described as playful. A few feet away from the tip of Figueredo’s tongue, we can see five straitjacketed armatures, bent and collapsing across the surface of a low plinth. This work by Ivens Machado was described by critics alternately as derivative and courageous.26

Fig.3

Grupo Seguranca enacting Faixa da Seguranca at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Eduardo Carlos Pereira Archive

© Eduardo Carlos Pereira

Fig.4

Grupo Seguranca enacting Faixa da Seguranca at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo/Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo

The group Segurança (Security) produced an equally memorable work for the Art and Communication section, which their proposal – published in the catalogue – describes as a recreation of ‘a piece of urban reality’.27 Utilising machinery and workers, the project involved the construction of a pedestrian crossing within the biennial’s pavilion (fig.3). Two road markings reading ‘PARE’ (STOP) delimited an area extending from the main exit to halfway up the ramp that connects the FBSP pavilion’s ground and first floors. On the day of the inauguration, road workers began laying the pavement. Surrounded by signs and barriers and releasing toxic fumes, Faixa de Segurança impeded the passage of the public and became embroiled in territorial conflicts with both a neighbouring artist and an on-site bank constructed within the pavilion.28 Its most controversial phase culminated in the destruction of the work by the group and the participants they had recruited. The pedestrian crossing was left strewn with debris including signage, bottles, food, packaging, printed matter and blood (fig.4). All traces were removed the next day.

Suitably broad, suitably technical

The presence of explicitly critical proposals begs the question of who invited them. The connection between the Art and Communication section and philosopher Vilém Flusser’s partially developed plans for the twelfth São Paulo Biennial as a whole has been acknowledged by Vinicius Spricigo and others.29 But this relationship alone does not account for the final exhibition itself, nor for the works that were there, particularly those accepted on the basis of a written proposal and realised in situ within the pavilion. Whereas most of the international names in this section appear in Flusser’s plans, none of the Brazilian participants do.

The conditions that made this form of participation possible were shaped by the FBSP’s pursuit of organisational reform. This process had been pushed forward by Brazilian artists and critics since 1966, when Maria Bonomi, Salvador Candia, Maria Eugenia Franco and Fernando Lemos compiled a report entitled ‘For a Restructure of the São Paulo Biennials’.30 The FBSP appointed artistic advisory groups to provide further recommendations, and potential changes were also raised for discussion within two International Art Critics Roundtables, held in parallel with the tenth (1969) and eleventh (1971) editions. This process of reform conveyed several consistent concerns. One preoccupation was how to define and support new forms of artistic practice. Another was the São Paulo Biennial’s mechanism for assembling an international show – a model based on the Venice Biennale whereby artworks were solicited via official agencies and displayed by nation. In June 1969, this process of reform coincided with the call for an international boycott. As well as causing several nations to withdraw, the call catalysed an alternative tactic, namely a consciously critical approach to participation. The simultaneous forces of reform, experimentation, international withdrawal and critical intervention shaped two thematic shows, featuring invited Brazilian artists, within the tenth and eleventh editions.

Prior to his decision to join the international boycott, the French critic Pierre Restany had been the first to propose an entirely thematic biennial. His initial idea – to replace ‘abusive national distinctions’ with ‘a suitably broad, suitably technical theme’ – arrived on the desk of FBSP President, Francisco (‘Ciccillo’) Matarazzo Sobrinho, in August 1968.31 From Matarazzo’s perspective, Restany’s idea was both excellent and impracticable. Thus, they reached a compromise: to invite artists chosen by Restany via their respective national channels. Restany’s biennial within a biennial, assembled according to the theme of Art and Technology, would – it was hoped – serve as a rehearsal for ‘how a future world exhibition could be established’.32 Restany did not resign until June 1969, and both the scale and promise of his proposed thematic exhibition contributed to the impact of the international boycott.33

A neon, wood and steel sculpture by the Greek-American artist Chryssa – despatched prior to Restany’s resignation – was among the stranded works of art selected for the Art and Technology section to arrive and be exhibited in São Paulo in 1969. A review published by the New York Times took Chryssa’s partially assembled artwork, The Gates to Times Square 1966, as a synecdoche of a biennial that its headline described as ‘awful’.34 As Caroline Schroeder notes, however, the tenth São Paulo Biennial also included Novos Valores (New Values), an important exhibition of work by young Brazilian artists brought together according to their shared interest in working beyond traditional media.35 This, she argues, was the first step towards establishing a critical presence at the biennial.

In Restany’s absence, the question of national representation entered into wider debate via the first International Art Critics Roundtable, held during the opening week of the 1969 edition. The meeting resulted in an agreement to maintain the use of discrete displays organised by participating nations, on the premise that proposed alternatives would ‘reaffirm the superiority of the centres already considered most prestigious’.36 In the case of Restany’s unrealised Art and Technology exhibition – whose chosen participants were restricted to the critic’s own networks – such reasoning is not without grounds.37 While national representation would be maintained, however, those assembled also agreed that this should be complemented by the inclusion of historical retrospectives and thematic contemporary shows.

The national versus the thematic was not the only topic under discussion. While Restany was still developing his Art and Technology exhibition from Paris prior to his resignation, an advisory group of artists and critics (Comissão de Artes Plásticas) had set to work in São Paulo. When the group disintegrated in June 1969, it left the FBSP with a series of recommendations. These included the removal of medium-based categories and the introduction of a critical seminar to the biennial’s programme. The discussion of these more experimental approaches continued within the first Roundtable, resulting in a list of possible measures: a permanent organising committee, interim research exhibitions to show ‘developing possibilities’, the inclusion of forms of art involving ‘human participation’ (‘happenings, parangolés, kinetic art’) and an institutional commitment to both art as research and freedom of expression.38

The underlying themes

Despite being a key proponent of the 1969 boycott, Restany returned to the FBSP just six months after his resignation, with a revised proposal for the eleventh São Paulo Biennial (1971).39 Another early supporter of the boycott, the Argentinean critic Jorge Romero Brest, had also changed his stance by 1970. In that year, he accepted an invitation to judge the first national biennial and drafted a project for the 1971 edition centring on the ‘art of the proposition’, with works to be produced in situ and debated within a parallel symposium.40 Neither Restany’s nor Romero Brest’s proposal was realised. There were in fact five cross-national exhibitions tabled for 1971, but none of these happened.41 What did take place, however, was a second International Art Critics Roundtable and another thematic show of invited Brazilian artists, Proposições – Arte, Vida, Ciência, Tecnologia (Propositions – Art , Life, Science, Technology) selected by a new advisory group, the Comissão Técnica.42

Restany’s orphaned theme, Art and Technology, was on the agenda of the Second Roundtable alongside an alternative: Art and Communication, as suggested by the chair of the event and President of the International Art Critics Association (AICA), René Berger. As well as gaining AICA validation for the 1971 Roundtable, the FBSP had secured the presence of international critic-directors including Umbrio Apollonio (Venice Biennale), Jacques Lassaigne (Biennal des Jeunes, Paris), Dietrich Mahlow (Kunsthalle Nuremberg and the Nuremberg Biennial) and Romero Brest.

The majority of those assembled duly outlined their responses to the proposed themes, but Romero Brest announced that had come to São Paulo in order to bring an unspoken undercurrent to the surface. He had come to acknowledge the reasons for the boycott, to utter the word ‘dictatorship’, and to insist that the only valid plan for any future biennial would be to face up to these facts:

It has come to my attention that everyone is avoiding the underlying theme. The underlying theme is that the biennial was politically boycotted by many artists around the world, it has been boycotted again this year, and it will be boycotted again in 1973 … The question must be faced, and I think that the authorities of the Biennial may or may not want to face it. Well, now that we are here as a group of independent critics, let’s face it … Let’s examine why the phenomenon of boycott happens.43

To be present, but critically so, was a stance also articulated by Teresinha Soares, who was one of two artists exhibiting within Proposições to be invited to take part in the Roundtable.44 In her statement (which included a take-down of the chair’s ignorance of the country in which he was speaking), Soares voiced her opposition to the boycott by referencing Berger’s proposed theme: ‘the weapon of the artist is precisely communication, what they do with their work, their communication, their protestation’.45

The Secretary General of the FBSP, Mário Wilches, concluded the proceedings with phrases later used to frame the twelfth São Paulo Biennial: the biennial as a laboratory; the work of art as a proposition; the need to both speak to the ‘anguishes and indignations’ of a younger public and to engage new technologies of communication.46 But within a nation under technocratic-military rule, the themes under discussion produced other associations. The art historian Clarival do Prado Valladares remarked that from the point of view of the ‘fenômeno brasileiro’ (Brazilian phenomenon) there was no creative relationship between art, technology and communication. Rather, these terms were represented by a culture of consumption and a form of ‘cyber-governance’, whereby information and counter-information had become an instrument of national security, encircling some and rewarding others. Here, Prado Valladares was likely alluding to Médici’s national information system (SISNI), which was by 1970 extending its reach into universities and public bodies via a web of informants and Security and Information Advisory (ASI) units.47

A certain indifference

Fig.5

Banco Nacional de Habitação stand at the tenth São Paulo Biennial (1969)

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo/Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo

In the wake of the boycott, the FBSP repeatedly declared its commitment to freedom of expression. But while the official government stance was not to intervene in the biennial, the event was a convenient platform for its interests, notably the Banco Nacional de Habitação (BNH). This national housing bank was the regime’s central mechanism for incentivising urban development and home ownership, offering payment plans to both the middle classes and those re-housed in the process of urbanisation and desfavelização (the demolition of informal housing to enable redevelopment). The BNH had been the sponsor of the biennial’s architecture section since 1967 (fig.5), and at the time of the second Roundtable it was the subject of a special exhibition that shared the pavilion’s third floor with Proposições.

The second Roundtable was a crucial moment for the FBSP to gain international support for its proposed reform. Prior to the event, Matarazzo sought the support of Médici’s increasingly active public relations operation, the AERP, a ‘special advisory’ that was the origin of notorious slogans including ‘Brazil – love it or leave it’ and – accompanying Médici’s push to colonise Amazonian territories – ‘men with no land for land with no men’.48 The AERP also produced films for television broadcast. The regime had been incentivising the purchase of home television sets since 1968, and a substantial percentage of the population could now tune in to watch an AERP vision of Brazil as a hardworking, prosperous, racially harmonious, three-time world-cup winning nation, cutting its way through the Amazon in the interests of national integration, pursuing urban and industrial development with zeal.49

Before the Roundtable, the FBSP drafted an internal memorandum, which was shared with the chief of the AERP, Colonel Otávio Pereira da Costa.50 An early version states the case plainly: the intended purpose of the biennial’s thematic programme was to ‘demonstrate the inexistence of censorship or restrictions’ on the part of the government and biennial alike.51 The final draft presents the biennial’s proposed renewal as one necessary for its survival as ‘a true assembly of nations’, which would be likely to reflect positively on Brazil. In this, it carefully notes that ‘our current art sector (conceptual, cybernetics, kinetics, technology, accidental, etc.) does not register ideological concern and when this may exist, the message becomes so diffuse that it leads to nothing’.52 The FBSP’s claim that contemporary forms of art were mute and ineffectual is a convenient point of rhetoric, one that possibly did not align with the FBSP’s actual views on the socio-political implications of contemporary art.53 Such deflection, however, also implied that the institution could not provide a narrative that would allow critical messages to be widely understood.

After the close of the Second Roundtable, the FBSP established a Technical Secretariat to develop a full thematic proposal for the twelfth São Paulo Biennial. Vilém Flusser was appointed as a member of this group and went on to develop a cluster of subsidiary ideas relating to the agreed theme of Art and Communication. Working from Europe, Flusser developed a new system of organisation whereby ideas related to specific artists would be used to create interdisciplinary teams involving Brazilian participants. While Flusser awaited Matarazzo’s approval, the number of artists and related ideas steadily grew from eight to twenty-one: the apartment; furniture; the environment; happenings; the aesthetic gesture; the influence of African culture; folklore; the social dimension of art; food; press animation;54 theatre and music; agro-villages and civic centres; the primary school; psychology; trash; open circuits; sculpture in question; images of the cosmos; art and hospitals; and fashion, all of which would be accompanied by a ‘dynamic’ exhibition catalogue.55 Like Restany and Romero Brest, Flusser was proposing something both ambitious and, given the importance of national representation to the FBSP’s financial model, impossible.56

In September 1972, Flusser and the art critic Antonio Bento were invited to present the project at the AICA general assembly in Paris, but it was not until late October that the FBSP granted approval for the projects they were then aware of. In a belated reply to Flusser, Matarazzo reminded the philosopher of the need to assemble the exhibition by means of existing diplomatic channels, and that conventional national representations would also be accepted.57 Suggesting concern over how the cost of Flusser’s plans might be met, Matarazzo mooted possible means of financing some of the ideas proposed thus far: Daniel Spoerri’s proposed project on food might be financed by the Brazilian Association of Food Producers; Joseph-Aurélien Cornet’s project on African culture could perhaps be funded by a television channel or a ticketed show;58 and Horia Damian’s interest in agro-villages may be of interest to the BNH, involved as it was in the ‘re-urbanisation’ of the Trans-Amazonian region.59

Three days before Matarazzo’s letter, Wilches had been to Brasília. In his meeting with Brazil’s Ministry of Cultural Affairs (Itamaraty), the themes of African cultural influence and Amazonian agro-villages had been picked out as of interest to the government. It was also remarked that Flusser’s project presented no political conflict. His ideas were deemed excellent and the Ministry had no interest in interfering. The only possible risk was ‘a certain indifference – major or minor’ on the part of Itamaraty if the event were to bring the country into disrepute.60 Reading between the lines, the prospect of ‘indifference’ on the part of the Ministry for Cultural Affairs, which could fund international cultural engagement, could have been a veiled threat to withdraw financial support.

The great laboratory of ideas

While in Europe in 1972 and working on plans for the biennial, Flusser decided to leave Brazil for good. By early 1973, perhaps disillusioned by the compromises his plans had been subjected to, his correspondence with the FBSP came to an end. The remaining members of the Secretariat – Wilches, Bento and the artist Bethy Giudice – began to transform his partially developed plans into parameters for the twelfth São Paulo Biennial. The ideas Flusser intended as focal points for cross-national teams were taken as a list of themes, to which national agencies could respond if they chose.61 The least developed aspect of the project was the involvement of Brazilian artists. With Flusser gone, the remaining members of the Secretariat deployed a technique rehearsed by the FBSP’s national biennials: a process of regional selection.62

One hundred Brazilian artists exhibited in the biennial. All were selected via regional juries but could also apply specifically to the Art and Communication section, with final selections approved by the Secretariat. Artists across the country were encouraged to participate in the reconceptualisation represented by this section. At a colloquium in the north-eastern state of Paraiba, Giudice introduced the ‘dynamic infrastructure’ of this ‘great laboratory of ideas’, describing it as one designed to permit the simultaneous creation, activation and public reception of works of art.63 Proposals could be collective and interdisciplinary, and participants were encouraged to embrace the work of art as a process, intended or not to result in any predetermined physical form.64

If they applied to the Art and Communication section, Brazilian artists were subject to the agreed criteria and regulations of an international thematic show. They were therefore both permitted and encouraged to propose works taking a variety of forms, including research, happenings, symposia, individual or collective experiments. The practical implications of a proposal system – one put together as a hasty solution to the disintegration of Flusser’s proposal and informed by artistic advisory groups’ emphasis on art as experimental research – were that artists from across Brazil could apply as individuals or teams, and with propositions rather than already-existing works. It created the conditions that allowed the twelfth São Paulo Biennial to be occupied by collectives representing various parts of the country, whose works would unfold within the event.

São Paulo, 5 October – 2 December 1973

The twelfth São Paulo Biennial opened little more than three weeks after the military coup d’état in Chile, and on the eve of what would come to be known as the Yom Kippur War. On the day of the inauguration, the city of São Paulo was on high air pollution alert. Guests arrived, eyes already streaming, into a pavilion stinking of hot asphalt.65 It was not widely known then that Médici had conspired with Richard Nixon to topple Salvador Allende; neither was it known that the war that would begin the next day would precipitate the first international oil shock of the decade and, in turn, Brazil’s economic decline.66 After three years of record-breaking growth, Brazil’s ‘economic miracle’ was nearing its zenith, and the biennial opened to a nation told it was thriving, in a city under construction, entering the rapid verticalisation and extensive spread with which it is now synonymous.

The material remains of this biennial offer little with which to assemble a history, not least because this edition included an unprecedented number of works exceeding the ontology of a single and stable object. It included works that were event-based and performative, as well as multi-sensory environments, the effects of which would not be registered by photographs. This biennial did not have the curatorial framing or interpretative apparatus now common to large-scale exhibitions of contemporary art. The catalogue offers no substantial rationale for the theme of Art and Communication, no interpretation of projects included within this section, and no biographies for those that produced them. The available source materials include incomplete photographic documentation of the biennial itself and the sometimes unreliable witness of art-critical reception.

More detail, however, is given by Brazilian academic research relating to specific projects. Walter Mariano has contributed foundational work on the Etsedron group from Salvador, Bahia, who participated in the biennial for the first time in 1973.67 Daiana Schvartz’s study of the archives of Elke Hering, an artist involved in ‘Projeto Santa Caterina’, provides a description of and context for the realised work, exhibited under the title Indian Project (Projeto Indio).68 The proposal-poem ‘Urban Anthropophoria’ relates to the group’s presentation of audio-visual documentation of a 1972 project in the nearby Vila Mariana district, which has become a reference point for urban interventions.69 Karen Debértolis’s study of the multi-faceted career of Joana Lopes, the co-instigator of the proposal ‘Anthropomagic Village in the Land of the Red Feet’ (Aldeia Antropomágica na Terra dos Pês Vermelhos), provides insight into how this project was informed by Lopes’s earlier experiences.70

As Bruce Altshuler noted in 2014, one of the ‘great lacunae’ of exhibition history is a lack of information concerning non-expert responses to past exhibitions.71 There are indeed no accounts that document the general public’s reaction to the collective proposals realised at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial. Some of the works, however, would have been difficult to avoid or ignore. Outside, visitors would see an inflatable dome bulging out from the side of the pavilion, housing a collective and participatory work named Open Project (Projeto Aberto).72 On entering, they would need to pass Figueredo’s mouth and Machado’s straitjackets, and then negotiate Faixa de Segurança to get to the first floor’s central atrium and the pavilion’s open, spiralling ramp.

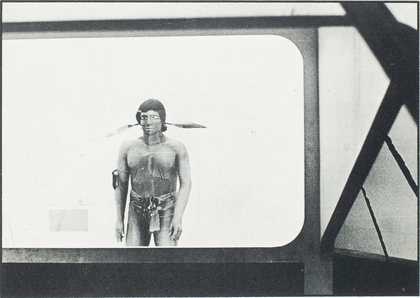

Fig.6

View of the central atrium of the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973) showing Projeto Índio by Arno Vogel, Elke Hering, Maria de Lourdes Menezes and Paulo Rocha at the centre of ground floor

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo/Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo

Fig.7

Projeto Índio by Arno Vogel, Elke Hering, Maria de Lourdes Menezes and Paulo Rocha illustrated in Argumento, São Paulo, no.3

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo/Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo

A photograph of this latter space (fig.6) allows a glimpse of Indian Project: a canopy stretched over a white cube; a small crowd huddled outside. As Schvartz explains, this hooded cube was a glazed showcase, displaying at its centre a large painted terracotta figure (the ‘Indian’) (fig.7) surrounded by objects made from an industrialised material (acrylic). The internal lighting was set on a timer so that the lights would suddenly switch off, transforming the treated glass into a mirror that reflected back the public’s gaze. One critic described his reaction to this experience: ‘when the figure of the Indian is darkened and we are illuminated, he is the one who criticises us. We feel ashamed to be there’.73 The group’s proposal for Indian Project targeted the curiosity of ‘civilised’ citizen’s toward indigenous communities, and the shame felt by this art critic indicates that this had hit home. Faced with his own reflection, caught starting at the terracotta figure, perhaps he recognised such an attitude in himself.

The group’s intent was to connect a commonplace othering of indigenous peoples to their wider marginalisation by ‘industrial civilisation’. At this time, such marginalisation was evident in a widespread colonisation of indigenous territories, carried out in the service of urban and industrial development. For the group who proposed Indian Project, this situation had particular relevance. Their home state, Santa Caterina, is largely identified with a population of German heritage, to the exclusion of those living in its vast indigenous territories. By 1973, indigenous communities including the Xokleng-Laklanõ had been subject to more than a century of colonisation, the effects of which had been researched by the ethnographer and adviser to Indian Project, Silvio Coelho dos Santos. In 1972, work had begun on a new dam situated within Xokleng-Laklanõ territory, designed to protect the city of Blumenau while leaving Xokleng-Laklanõ land vulnerable to devastating floods.

In certain places

Fig.8

Etsedron’s Projeto Ambiental I at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973), illustrated in Argumento, São Paulo, no.3

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo/Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo

The majority of works included within the Art and Communication section were displayed on the third and final floor of the pavilion. The plan shows areas reserved for contributions from Canada and France, an audio-visual screening room, and a small architecture section. The spaces allocated for Brazilian participants are indicated by blank shapes, one of which was occupied by Etsedron’s Environmental Project I (Projeto Ambiental I) (fig.8). This work was awarded a prize and frequently featured in press coverage of the biennial. The responses it elicited – positive, negative, sometimes dismissive – initiated a debate that gained depth and momentum when the group participated in the thirteenth São Paulo Biennial two years later.

Etsedron’s space was delimited by a ground of red earth, marked with pathways and populated with plants, figures made from tough twisted vines and the frame of a taipa (mud) hut. The project, coordinated by the artist Edison da Luz, involved fourteen participants, who contributed dance, music, film and documentation to establish a dynamic environment. This was the first of a series of Etsedron works to begin within a period spent living with communities in north-eastern Brazil.

For Environmental Project I, the group stayed in Vila Guajeruz, a fishing village close to the Bahian coastal town of Arembepe. As Mariano notes, this constituted a phase of quasi-ethnographic research, through which the group learned local construction techniques. The full proposal for this project, submitted to the FBSP by Etsedron, conveys how the group came to understand and be absorbed by the daily life of the community in Vila Guajeruz:

We understood with them the importance of the river that passes by, its ebb, its flow, its pollution by Tibrás.74 We attended births, we prayed at vigils, we went with them to candomblés and sambas de roda, we lived with Ângelo, Iansã’s horse who receives the Boiadeiro.75 We lacked telephone, electricity and television, which was until recently considered a punishment but can also be a blessing. Bathing in the river. Mysticism, beliefs, leaf and root remedies and the strange mythology passed from mouth to mouth ended up affecting us.76

Within the twelfth São Paulo Biennial, Etsedron aimed to present a reality unacknowledged by the artistic milieu and government alike. While occupying the contemporary language of the ‘environment’ or ‘happening’, the group conveyed an aesthetically, economically, topographically and ontologically distinct reality – one that exposed the collateral effects of Brazil’s economic success and expressed the distinct mode of relating to the world they had experienced in Vila Guajeruz. This drive to use the biennial as a site for producing and exposing a counter-reality was a consequence of the FBSP’s adoption of regional selection, coupled with its expanded criteria. It can also be seen as a tactical opposition to the false consciousness fomented by Médici’s AERP.

The biennial’s regional selection process and openness to work by collectives drew responses from sites of activity not previously connected to a professionalised art world: those where artistic practice bridged experimental theatre, cinema, popular culture, ethnography and community action. Among such sites was the recently established State University of Londrina (UEL), in Northern Paraná, from which the proposal for Anthropomagic Village emerged. By realising this work at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial, Lopes had hoped to ‘bring to light’ the work of Grupum, a theatre group she created when she joined UEL in 1971.77

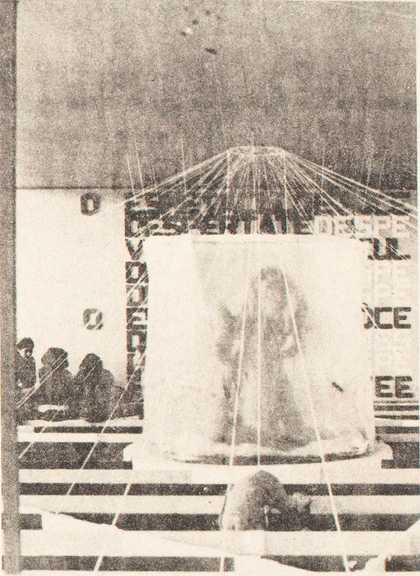

Fig.9

Aldeia Antropomágica na terra dos pês vermelhos at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973), published in Tavares de Miranda, ‘Com os Brasileiros, a riqueza da variedade’, Folha de São Paulo, 5 October 1973, p.3

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo/Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo

The distinctive materiality of red earth was also an element of Anthropomagic Village, where it represented the bright soil of Northern Paraná, which lends the nickname ‘red feet’ (pês vermelhos) to its inhabitants. Like Environmental Project I, this work occupied a large space on the third floor. Its existence, however, is barely registered by the archive, where all that remains is a grainy and mis-captioned newsprint image (fig.9).78 My inability to understand of what this image represented was resolved by the work of Debértolis, and in conversation with Lopes.

Fig.10

Aldeia Antropomágica na terra dos pês vermelhos at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Joana Lopes Archive

© Joana Lopes

Fig.11

Aldeia Antropomágica na terra dos pês vermelhos at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Joana Lopes Archive

© Joana Lopes

Fig.12

Aldeia Antropomágica na terra dos pês vermelhos at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Joana Lopes Archive

© Joana Lopes

A track of red-earth footprints led up the pavilion’s spiralling ramp to the third floor, where it ended at the entrance to a large construction with three open sides and a traditional beaten-earth floor, the back wall of which bore phrases including ‘wake up’ (desperte-se) and ‘the spectacle is you’ (o espetáculo é você). The floor of this theatre-like construction was traversed by raised beams, creating awkward subdivisions for the public to clamber into or across, their headspace impeded by threads connecting the beams to the ceiling (fig.10), where they marked out an image of the Brazilian flag. At the centre of the space, a circular raised stage contained figures trapped within a transparent plastic tent (fig.11), a role alternately played by actors and puppets made from burlap coffee sacks, which otherwise lay, as if abandoned, within the space (fig.12).

Fig.13

The Teatro-Escola Pindorama

Joana Lopes Archive

© Joana Lopes

The group who proposed Anthropomagic Village included Lopes, the artist and Grupum member Dijalma di Souza, and the Teatro-Escola Pindorama: a theatre school and Grupum offshoot based in a disused laundry on the eastern fringe of Londrina.79 Its students were the residents of a nearby and recently completed complex of single-storey houses, the Conjunto Habitacional (Cohab) Pindorama, built for and sold to former occupants of the demolished Vila do Grilo favela. In Londrina, a large proportion of those living in the city’s favelas worked, or sought work, on coffee plantations. At the start of the 1970s, their labour conditions deteriorated from secure contracts to non-unionised day labour.80 The architecture of the Cohab Pindorama inhibited its residents’ ability to gather, interact and organise.81 When it was first completed it had no community facilities. This gap was filled by the Teatro-Escola Pindorama (fig.13).

The exercises in drama and movement that Grupum practiced with the Cohab’s residents were informed by a methodology Lopes had developed through her experiences in popular education. In 1965 she began working for the Escola Rural Isolada de Itágua, a school in a fishing village on the north coast of the state of São Paulo, which taught literacy according to Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy.82 In 1969, Lopes was invited by the founder of the Ação Popular (Popular Action) movement, Herbert ‘Betinho’ de Souza, to support a theatre production in Greater São Paulo’s ‘ABC’ industrial region involving workers aged between nineteen and twenty-five.83 This was a formative experience for Lopes’s understanding of theatre as a form of communication and agent of transformation.84

Lopes devised Anthropomagic Village as a deliberately restrictive space, one that forced the public to adopt awkward or uncomfortable movements as they moved about in search of a vantage point on the tent at its centre. The work also included elements associated with Northern Paraná: the red earth floor, the abandoned coffee sack figures and di Souza’s improvised music on the theme of agricultural day-workers (boais-frias). Lopes recalled that the visitors who appeared to grasp these subtexts were predominantly younger, of student-age. In relation to this, she remembers a certain distinction between the ‘second floor people’ (those drawn to the floor below, which contained the Kandinsky exhibition, the FBSP salesroom, two historical exhibitions of Brazilian art and official national exhibitions) and those who spent time on the third floor.85

Pale metaphors: The third movement of Faixa de Segurança

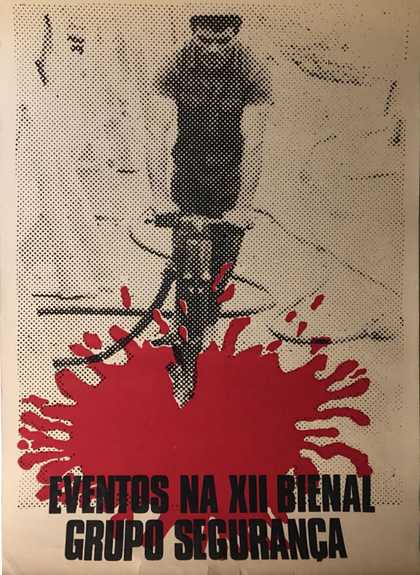

Fig.14

Eduardo Carlos Pereira, poster for Grupo Seguranca’s performance at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Eduardo Carlos Pereira Archive

© Eduardo Carlos Pereira

Proposals for the Art and Communication section came in from existing groups, such as Grupum and Etsedron, but the opportunity to work collectively also spurred individuals to work in new ways. Both Indian Project and Faixa de Segurança were collective projects that included an artist-member who had been selected for Brasil Plástica ‘72, part of the FBSP’s national edition the year before. As Renata Zago notes, this second national biennial was drawn into ostentatious commemorations of Brazilian Independence.86 In this context, Eduardo Carlos Pereira, a young artist and architecture student who later formed part of Grupo Segurança, exhibited a photograph of a worker pushing a pneumatic drill under the title Dominization (desominização; an increase in dominion, expansionism, territorialisation) (fig.14).

Pereira had been part of the first cohort to enter a new Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at Braz Cubas University and, like the other members of Segurança, was from Jundiai, a city just north of São Paulo. Three of the group’s four members were students, living in São Paulo’s old downtown, a neighbourhood that was then a distinct milieu populated by journalists, artists, writers, actors and students, theatres, bars and cinemas.87 Press reports, which refer to Faixa de Segurança in dismissive or sensationalist terms, do not convey the planning that underpinned it. To realise this work, the young group contracted paid workers and co-ordinated many additional participants, a process that Pereira has described as ‘difficult and precise’.88 One member’s father ran a construction company, which facilitated support from Jundiai City Hall and permitted Segurança to employ roadworkers and security guards.89 The headline-grabbing happening that ended the event was part of the dramaturgy devised for a work conceived as a series of four movements, each explained within a detailed proposal submitted to the selection jury.90 Press reports give the impression of a sudden outbreak of violence, but the parameters for this scene had been shared with the FBSP.

Fig.15

Pavement under construction on the entrance ramp during Grupo Seguranca’s performance of Faixa da Seguranca at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Eduardo Carlos Pereira Archive

© Eduardo Carlos Pereira

As outlined, the work was to begin with the ‘static and organised’ assembly of materials and workers.91 The first movement would be announced by a siren, calling for work to commence, and the construction of the pedestrian crossing would occur in two stages: the preparation and laying of a stone and hot asphalt pavement (fig.15), and the painting of white stripes. The second movement would be the substitution of roadworkers with security guards to protect the freshly painted pavement. In a third movement, a removal crew would rush in and a struggle would ensue. The fight would escalate and meanwhile, in order to ‘maintain a relative level of security’, musicians would provide gentle entertainment. In the end, ‘some would be declared the winners and others the losers’. The dead would be covered and mourned, the victors would be celebrated, and trophies would be awarded to heroes. The fourth, unrealised, movement was the screening of a film documenting the prior stages, which the group intended to show alongside the work’s remains.

Fig.16

Comind Bank under construction during Grupo Seguranca’s enaction of Faixa da Seguranca at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Eduardo Carlos Pereira Archive

© Eduardo Carlos Pereira

In reality, however, Segurança encountered interruptions. On the day of the opening, both the FBSP’s own security and the military police tried to prevent the group from blocking the ramp.92 They were remarkably defiant. A photograph published by the Estado de São Paulo depicts the Brazilian Vice-President Augusto Rademaker, in full entourage, squeezing his way past their construction site. The following day it became evident that the FBSP had leased an area of the ramp to Comind (Commerce and Industry) bank, whose temporary premises impinged on Segurança’s space (fig.16). A neighbouring artist objected to the word ‘PARE’ (STOP) being close to her work and scraped it from the floor. An agitated Matarazzo hovered about the space, making failed attempts to call work to a halt; Wilches’s intervention veered between encouragement and castigation.93

Fig.17

The third act of Grupo Seguranca’s Faixa da Seguranca at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Eduardo Carlos Pereira Archive

© Eduardo Carlos Pereira

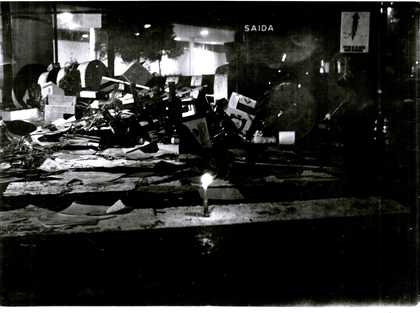

Fig.18

The third act of Grupo Seguranca’s Faixa da Seguranca at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Eduardo Carlos Pereira Archive

© Eduardo Carlos Pereira

Fig.19

The aftermath of Grupo Seguranca’s Faixa da Seguranca at the twelfth São Paulo Biennial (1973)

Eduardo Carlos Pereira Archive

© Eduardo Carlos Pereira

Nevertheless, the movements continued, up to and including the fight between the group’s security guards and the invading removal crew. This scene was accompanied, as planned, by a piano recital, attended by an elegantly dressed crowd (fig.17), at first quietly drinking champagne, then cramming sweet snacks into their mouths, smashing their glasses and throwing the bottles. This movement took place at 10pm, when the biennial exhibition was due to close, and Segurança had been given permission to dim the lights on the ground and first floors. Any member of the public making their way to the exit and unaware of what was happening would walk into a scene of escalating conflict (fig.18). At its peak, this involved the throwing of various missiles: bottles, chairs, road signage, food packaging, printed material and potatoes (fig.19). This orchestrated atmosphere of violence, confusion and panic culminated in the visceral shock of three barrels of blood being tipped down the ramp and over the pedestrian crossing.94

In retrospect, the associations created by Faixa de Segurança seem clear: the military regime’s National Security Law (Lei da Segurança Nacional); omnipresent urban and industrial development; entertainment as pacifying distraction from ongoing violence; gluttonous consumption; and blood on the floor. But the possibility of any critical meaning was not acknowledged by the press.95 The violent atmosphere produced by its third movement was said to be gratuitous. At a time of routine press censorship, even sympathetic newspapers were unlikely to link pollution, vigilance, violence, destruction or greed with the state of the nation. And the FBSP was also under pressure to uphold its promise: that contemporary practice was incapable of any intelligible political stance. In this, the group’s youth was an advantage; they were dismissed as immature mal-educados.96

The question of what motivated the work was addressed by a folded broadsheet distributed during the third movement. In the text published within, the group acknowledged the contribution of the Comind bank, whose unwelcome presence helped to articulate the work’s ‘underlying reasons’.97 The reasons themselves are stated in a few words that require some explanation: ‘because potatoes are pale metaphors, and structures organise serpentine systems’. In a doubled allusion to logics of division,98 the metaphorical potatoes point to an analogy which appears in Machado de Assis’s 1891 novel Quincas Borba: two starving tribes face a field of potatoes sufficient only to fuel one tribe’s journey to the next slope, where potatoes are abundant. The only apparent answer is for one tribe to exterminate the other and collect the spoils. The tale encapsulates a fictional philosophy that conceives war (and implicitly, capitalism) as an acceptable law of natural selection. Segurança’s reward was not the potatoes. It was the ignominious removal of their work prior to its final movement, and an enduring fear that their self-exposure would have consequences.

To the conquered, hate or compassion

This explains the joy of victory, anthems, cheers, public recompense, and all the other results of warlike action. If the nature of war were different, those demonstrations would never take place for the real reason that man only commemorates and loves what he finds pleasant and advantageous, and for the reasonable motive that no person can canonize an action that actually destroys him. To the conquered, hate or compassion; to the victor, the potatoes.99

On meeting Joana Lopes, the first question I asked was how she remembered the twelfth São Paulo Biennial. Her answer was as ‘a tragic event’, inseparable from the circumstances of her dismissal from UEL in January 1974.100 By this time, it was clear that this outpost for staff and student resistance had been infiltrated. When Lopes was ejected, the Teatro-Escola Pindorama came to an end. At our second meeting, Lopes placed a small pile of papers into my hands: a DOPS (Department of Political and Social Order) file, documenting her surveillance by ASI units at both UEL and the Folha de Londrina newspaper, for whom she subsequently worked.101 What we now know of the political circumstances of this time may make both Lopes’s decision to bring her work to light, and the actions of Segurança, hard to comprehend. But the twelfth São Paulo Biennial offered a peculiar liberty. Outside the pavilion, citizens had no right to freedom of assembly; within, they were permitted to work collectively. And the biennial, although subject to boycott, was an exhibition that newspapers could cover with relative freedom.102

In 1975, the thirteenth São Paulo Biennial shifted away from the experimentation of its predecessor.103 The fourteenth edition (1977), however, coherently combined national representation with the presentation of works in defined cross-national sections, thus lending coherence to the exhibition as a whole.104 This decisive restructuring was not accomplished overnight or by a sole named curator. It was proposed and implemented by a newly formed body of artists and critics, the FBSP’s Conselho de Arte e Cultura (Art and Culture Council),105 and informed by more than a decade of experimentation, reversal, compromise and critique.

Shaped by an unstable process of organisational change, the twelfth São Paulo Biennial betrays the contingency between the biennial as exhibition and as institution. Despite Flusser’s ambitions, and those of Restany and Romero Brest before him, it failed to establish a new paradigm. Had their ideas been proposed at another time or under different circumstances, the twelfth São Paulo Biennial may have been held up as an exemplary exhibition. We are left, however, with other reasons to remember it, not least the still-searing relevance of the collective works that occupied it.

The call for international boycott in 1969 drew attention to the most brutal facts of the military regime, including state-endorsed censorship, kidnap, torture and murder. In spite of these risks, the collective works that occupied the twelfth São Paulo Biennial evidence the use of critical participation as an alternative means of expressing dissent. These now articulate the social and political context of this biennial more persuasively than any curatorial theme. They also convey another dimension of the military regime’s history. Grounded within diverse locations, each group had witnessed the impact of the Médici regime’s fostering of structural inequalities and environmentally exploitive policies, and their works thus address a form of violence that had become both physical and systemic. The legacies of this time did not end with the restoration of democracy. These collective proposals, hidden in plain sight within the twelfth São Paulo Biennial’s catalogue, now articulate a history of the present.