The Pre-Biennale de Paris

In the years following the coup-d’état of 31 March 1964, Brazil’s civic-military dictatorship strengthened its repressive apparatus by instituting a succession of legal instruments and norms. Coming into force in December 1968, the Institutional Act No.5 (AI-5) inaugurated the regime’s most violent phase. The measures it enforced provided tools to intimidate, repress and demobilise any opposition. The right of habeas corpus (protection against illegal detention) and freedoms of expression and assembly were suspended and peremptory dismissals permitted; mandates and citizens’ rights could be annulled and political trials were to be conducted by military courts with no right of appeal.

The existing use of surveillance and censorship was bolstered and the use of torture became systemic. Within the cultural sphere, references to the political context or questioning of social and behavioural norms were repressed.

The closure of an exhibition hosted by the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ) was a tipping point in the censorship of the visual arts and a catalyst for the boycott of the biennial. The exhibition, which featured artists selected to take part in the sixth Biennale de Paris (1969), was ordered to be closed before its opening night by the government department that had commissioned it.

Niomar Moniz Sodré Bittencourt, the owner of the Correio da Manhã newspaper and Director of the MAM-RJ, later reported on the cohesiveness of the group of artists selected to represent Brazil in Paris: ‘a beautiful and kindred team, united by a strong Brazilian accent’.

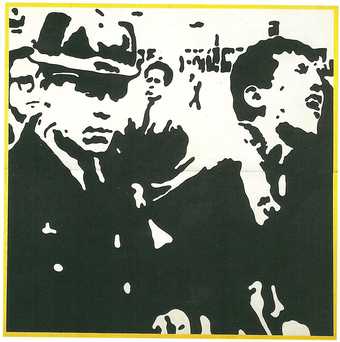

It was precisely this accent, however, that precipitated the exhibition’s end. Antonio Manuel exhibited one of his most recognisable works of this period, Repression Again: Here is the Consequence (Repressão outra vez: eis o saldo) 1968 (fig.2), which includes five red-panelled silk screens of police violence against students, each covered by a black cloth that could be raised by the public, revealing the images. Evandro Teixeira showed The Fall of the FAB Motorcyclist 1965 (fig.3), a photograph depicting the moment when a Brazilian Air Force official fell from his motorbike while escorting Queen Elizabeth II during her visit to Brazil. The image, taken by Teixeira when he was working as a photojournalist, had not been censored when it was published on the front page of the Jornal do Brasil in 1965. Three years later, however, it seemed overtly offensive in the eyes of the military. The Minister of Foreign Relations, José de Magalhães Pinto, attempted to justify the censorship by stating that MAM-RJ should have advised his Ministry of the works selected for the exhibition and avoided the inclusion of any ideological or political content.

In the wake of AI-5, the inventive and intellectual abilities of art were constrained at a moment when artists and critics were pushing for a greater understanding of its potential for social transformation. In 1967, on the occasion of the exhibition Nova Objetividade Brasileira (New Brazilian Objectivity) at the MAM-RJ, Oiticica had articulated a new vanguard: a critical position characterised by participatory forms of experimentation and challenge to the status quo.

Informed by his reading of political theorist Herbert Marcuse, Oiticica understood participation as a ‘dis-repression’, which he defined as the refusal of passivity and the adoption of a socially marginal position.

The following year, Pedrosa translated and published an excerpt from Restany’s 1967 manifesto ‘Against an International Mediocrity, Towards Generalised Aesthetics’ (Contro l’Internazionale della mediocrità, verso l’estetica generalizzata).

Describing ‘total art’ as ‘a generalised popular aesthetics’, Restany’s manifesto argued that art had changed its purpose and must now be ‘a collective metamorphosis that works in favour of all’.

In the commentary that follows his translation, Pedrosa outlines one of his most widely cited concepts: ‘Today, the conscious artist is making something unprecedented: the experimental exercise of freedom’.

Over the course of the 1950s, and during the first five editions of the São Paulo Biennial, Pedrosa had promoted concrete and constructivist art in tandem with his democratic and socialist politics. Following the civic-military coup, he took a stand against the regime’s authoritarian actions by publishing articles in the national press and engaging in meetings and marches. On 21 June, following the closure of the MAM-RJ exhibition and subsequent prohibition of the artists’ participation in the sixth Biennale de Paris, the ABCA-RJ met to define a series of resolutions. Pedrosa’s passionate protest, written on behalf of the association, was published as a manifesto the following day, and sent to state authorities and to the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) in Paris.

As well as referencing the censored MAM-RJ exhibition, the manifesto cited two cases of censorship that had occurred in 1968 – the closure of the second Bienal da Bahia, where artworks had been removed and organisers arrested, and the removal of works from the third Salao de Ouro Preto.

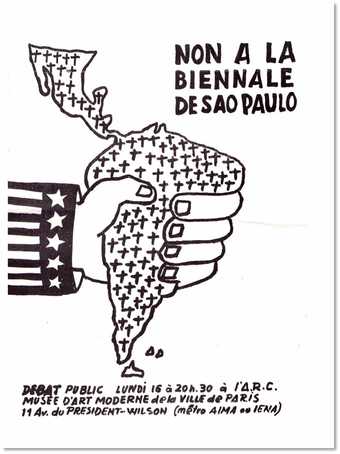

Less than a week before the manifesto was published, details of the same cases had been presented at the Paris meeting and included within the Non a la Biennale de São Paulo dossier. With information concerning repression and censorship crossing borders, efforts in Brazil and France started to come together.

The obligations of the art critic

The ABCA-RJ’s manifesto of 22 June was articulated as a defence of art criticism, a profession whose work was being constrained and interrupted by the regime. Its resolutions included refusing to participate in juries or accept positions in salons and other ‘official or officious art exhibitions’ in Brazil, whether publicly or privately funded, and refusing to select artists to represent the nation abroad.

The manifesto called for the abolition of visual arts censorship, which – unlike theatre and cinema – was being carried out ‘in an unorganised and deregulated fashion’.

This position was reiterated by Pedrosa’s article ‘The Obligations of an Art Critic in Society’, which was published by Correio da Manhã under the pseudonym Luiz Rodolpho on 10 July 1969.

Written in response to the official justification for censoring the MAM-RJ exhibition given by Pinto, Pedrosa’s article asserted that art could neither be judged according to ideological criteria nor understood as illustration or propaganda, because any apparent moral or political content was inseparable from its form.

The visual arts, Pedrosa argued, did not play a clandestine role requiring control and surveillance by secretive government departments; and neither were visual arts exhibitions comparable to live events, which were subject to censorship under the Brazilian constitution. Pedrosa also reminded readers of AICA’s mission, of which the ABCA was a member organisation, to ‘fight for consensus on the role of art critics’ as ‘qualified technical professionals’.

In Brazil, two professional associations – the ABCA and the International Artists Association (AIAP) – became key networks for sharing documents and debating a proposed boycott of the tenth São Paulo Biennial. The ‘official or officious’ exhibitions that the ABCA-RJ had agreed to boycott included the São Paulo Biennial. The manifesto also agreed, however, that withdrawing from previously agreed commitments should be optional, a clause permitting those already engaged by the FBSP to retain their roles. The São Paulo branch of the ABCA agreed to remove their representative from the biennial’s Visual Arts Commission and published a statement expressing their willingness to join the ‘combat against censorship and the struggle for creative freedom, in defence of the free exercise of art criticism’.

The resolutions published within the ABCA-RJ manifesto were contested by four local critics.

This led the ABCA-SP to criticise a ‘lack of unity’ that would, as Aracy Amaral noted, ‘provoke greater confusion among artists’.

Withdrawing from the biennial was a point of contention and uncertainty for artists, both those invited to take part in the exhibition and those planning to submit works for selection by the jury. AIAP members shared the ABCA’s repudiation of censorship, but the association decided against issuing any collective response to the call for a boycott. In late June, the Rio de Janeiro branch of the AIAP (AIAP-RJ) published a declaration defending creative freedom from judgements ‘enforced by officials who are not trained to assess the global values of an artwork’, which would threaten ‘any chance of legitimacy, stunting or limiting the professional practice itself’.

The statement referenced earlier cases of censorship, noting that ‘already in the eighth and ninth São Paulo Biennials, censorship had removed works by several Brazilian artists from the exhibiton’.

The AIAP-RJ urged artists to examine the facts and base their decisions over whether or not to participate in the biennial on ‘the solidarity necessary to achieve our nation’s cultural development’.

A letter from the artist Antônio Henrique Amaral in São Paulo to the critic Frederico Morais in Rio provides rare insight into the discussions taking place among AIAP members.

Recounting a meeting during which documents including the ABCA manifesto, AIAP-RJ declaration and the Non a la Biennale dossier were read to fifty artist members, Amaral describes a dynamic debate: ‘things change every minute. I am writing to put my ideas together and to inform you in Rio what is happening here. Reply, share, have your say!’.

Amaral predicted that artists registering for selection by jury would ultimately take the same stance as those rumoured to be declining invitations to take part. But he also reported that some artists believed that exhibiting was the more effective weapon against government censorship. Even under repressive conditions, they argued, artists should not stop producing, but instead maintain the struggle to ensure a ‘constant and challenging presence within areas to which they are assigned, such as biennials, galleries, museums, etc’:

Amaral reported that critics of the boycott also considered its implications for other exhibitions within Brazil’s circuit of contemporary art salons. He questioned the focus on the São Paulo Biennial alone, since censorship is ‘an imposition that reaches the whole national territory’, and asked where the line should be drawn: ‘If the artist does not send an artwork to the biennial, does that mean he won’t take part in any salons, ad infinitum?’.

From this perspective, taking part in the biennial can be understood as a local tactic, distinct from the methods of the international boycott. Rather than regarding the São Paulo Biennial as an extension of the regime, certain artists viewed its international stage – with delegations from other nations – as a potential site for mass critical participation. These artists believed that their absence would have little impact beyond their immediate milieu of artists, while large-scale critical participation would resonate further. Launching an attack from ‘the inside’ would be the ‘Brazilian way’ of contributing to a proposal ‘made by artists from abroad’.

Any written protest was likely to be restricted by press censorship, and therefore ineffective. Moreover, in the absence of a unanimous decision by Brazilian artists to boycott the biennial, the idea of rendering the exhibition empty would fail.

Others viewed the rising tide of protest initiated by Non a la Biennale as a force to which Brazilian artists could contribute. Some cited the FBSP as a reason to join the boycott. According to the artist Waldemar Cordeiro, it was ‘a senile and feudal institution’ unworthy of celebration, whose selection criteria did not meet the ‘real needs of current Brazilian art’.

Although at first he considered taking part in the biennial, Amaral was uncertain which direction to take. His fellow painters Arcangelo Ianelli, Alfredo Volpi and Samson Flexor were likewise undecided. All four, individually and at different times, eventually decided not to exhibit. But at the time of Amaral’s letter, July 1969, nothing was set in stone.

With the biennial scheduled to open in late September, discussions continued and art critics began to state their positions in the national press. Jacob Klintowitz viewed the boycott as a proposal ‘detached from the Brazilian and human cultural context’ and argued that the biennial’s relevance and achievements to date should be carefully considered before shutting this ‘door to culture’.

Geraldo Ferraz agreed, arguing that ‘passive abstention’ would have a significant impact on the biennial itself but no effect at all on the problem of censorship.

The artist and critic Arnaldo Pedrosa d’Horta took a balanced view, lamenting the fact that the boycott would deprive the public of knowledge of important works while empathising with the artists choosing to boycott: