Is there a quality that separates art produced in Minnesota from art, produced, say, on the West Coast of America? Is American art, as such, different from European art and, if so, are those differences embodied equally in the art of Minnesota and New York?

Lawrence Alloway1

In 1963, two years after arriving in New York from London to take up a post at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the British critic and curator Lawrence Alloway penned a short essay called ‘Whatever Happened to the Frontier?’. Written on the occasion of the Minnesota Biennial, and published in the Minneapolis Institute of Art Bulletin, the essay confronted the challenge of how to account for the local adoption of a historically global exhibition format, one that Alloway would return to consider in depth in his later book The Venice Biennale, 1895–1968: From Salon to Goldfish Bowl.2 The Minnesota Biennial presented for Alloway ‘an occasion to raise questions about the relation between regional, national, and international art’, an undertaking he related to ‘present attempts to locate specifically American properties in recent American art’.3 Such questions persist in recent critical projects that seek to understand the role and relevance of the local and the regional in the era of the global or transnational.4 At the centre of these debates, which inevitably reflect social, political and economic contexts as well as cultural and art historical ones, is the question of what we mean when we speak of American art.

Alloway’s essay articulates both the paradox and the politics of provincialism in American art and criticism in the post-war decades. He observed a tendency on the part of mid-century critics to define American art and those who make it by means of loaded geographical metaphors, according to which the progressive American artist was frequently cast as a frontiersman or pioneer. The art he produces is described as being, in the words of the critic John McCoubrey, for example, ‘possessed by the spaciousness and emptiness of the land itself’.5 This widespread assumption that linked art to the expansive American landscape embodied the continued romanticisation of wide open spaces that conjure the colonial myth of the ‘undiscovered’ continent as a blank slate. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the locational anxieties articulated in Alloway’s essay reflect not only the Europe-US cultural relations that would characterise much writing on post-war practice, but also the complex manner in which the category of American art was defined. If New York (for which read Manhattan) was the post-war thief of modern art, according to art historian Serge Guilbaut’s infamous assessment, then American art was regularly described in the Cold War period according to broader American tropes that drew on the loaded symbolic potential of the country’s history of colonisation and expansion.6

This article explores the ways in which provincialising rhetoric (that of the frontier and the Old West in particular) was deployed by critics and artists alike to assert, undermine or challenge the cultural asymmetries that art historian and critic Terry Smith would decry in his 1974 Artforum article ‘The Provincialism Problem’. In that essay, Smith proposed provincialism as operating both geographically and psychologically, describing it as ‘an attitude of subservience to an externally imposed hierarchy of cultural values’.7 It was driven by ‘the projection of the New York art world as the metropolitan center for art by every other art world’.8 Yet, though this competitive model of centre and periphery persists in much writing on art made outside of New York, I shall argue that for many the situation was less clear cut. In particular, for artists working in Los Angeles during the post-war decades, metaphors of the frontier, the pioneer and the cowboy were not merely deployed to reinforce or overcome cultural hierarchies, either deliberately or inadvertently, but were performed as a self-conscious assertion of cultural identity and agency aimed at destabilising the binary narrative of success and failure. While Terry Smith argued that ‘the provincial artist cannot choose not to be provincial’, I am arguing for a reverse manoeuvre, whereby artists in Los Angeles inhabited that position deliberately and strategically, performing provincialism in order to play one position off against the other and to reveal the ludicrous nature of the provincialist model.9

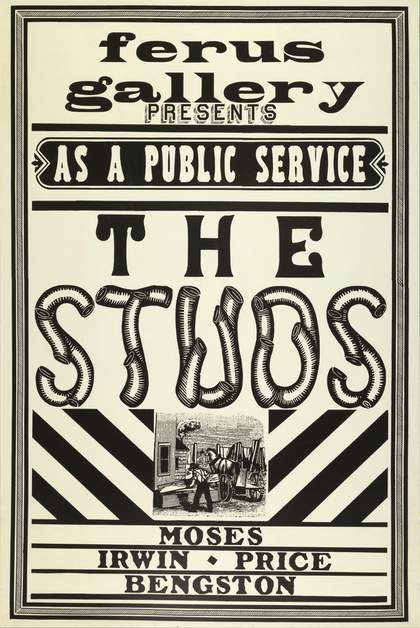

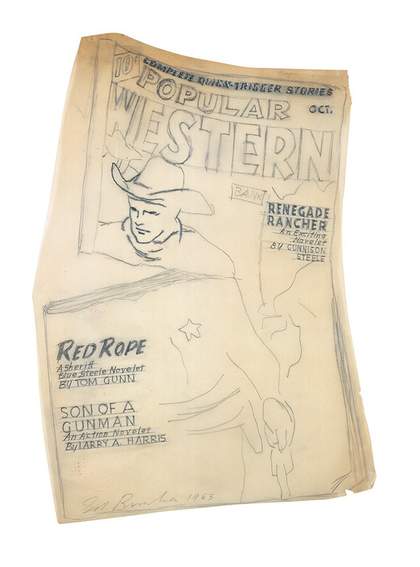

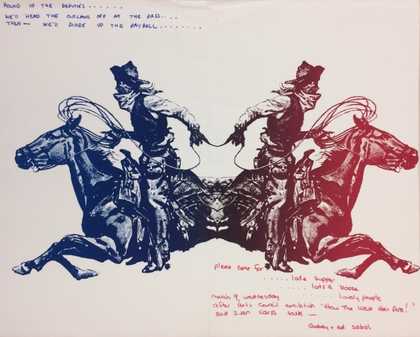

Fig.1

Poster for The Studs: Moses, Irwin, Price, Bengston at the Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles, December 1964

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York

Performing the frontier

One answer to the question that Alloway posed – whatever happened to the frontier? – is suggested by a 1964 poster produced for the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles to announce an exhibition of work by four Los Angeles artists (Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, Ken Price and Billy Al Bengston), a quadrumvirate grouped under the macho title The Studs (fig.1). Although the poster names the four artists, it does not depict them or their work, giving few clues as to what the exhibition will comprise. Nor does it deploy the mid-century modern aesthetic that might be expected of one of Los Angeles’s leading avant-garde galleries at that moment.10 Rather, the black and white design invokes an older point of reference via multiple textual registers, framing devices such as borders and cartouche, and imagery that might be described as outmoded in both form (resembling a woodcut) and content (a pioneer farmer chopping wood next to a horse-drawn wagon). Though the poster has a striking graphic impact, it requires some decoding, suggesting that its message is aimed firmly at a small coterie already familiar with the Ferus Gallery and its macho stable of artists, for whom the designation ‘studs’ was probably only partially tongue-in-cheek. In its curious invocation of the historical past in the post-war context, the design also hints at some of the tensions that would shape the Los Angeles scene.

Theatrical and eye-catching, the poster resembles the kind of public announcement one might imagine encountering in the Wild West, an allusion that is reinforced by the announcement of the Ferus exhibition ‘as a public service’. Its stylistic allusion to the past situates the self-fashioning of the Ferus group in the context of the post-war revival of the western as a genre urgently associated with American nationhood and its contestation. Post-war invocations of the frontier included the 1950s revival of famous nineteenth-century frontiersman Davy Crockett and the newly opened Disneyland’s Frontierland, which allowed theme park visitors to perform a pioneer identity even as they consumed the products of late capitalism that were its logical result.11 These popular cultural iterations, argues cultural historian Richard Francaviglia, ‘sustain[ed] the region’s past as a significant mythological element in American culture’, reflecting and reinforcing the role of frontier mythology in American cultural identity formation.12

The Ferus poster is not straightforwardly revivalist, however. It also reflects a productive countercultural reimagining of the American West, as embodied in the category defined by film critic Philip French and others as post-western on account of its broad concern with a critical deployment of ‘the West today’, and the tendency of its cultural outputs to ‘draw upon the western itself or more generally “the cowboy cult”’.13 The Ferus poster similarly stages the historical frontier in the context of the post-war contemporary in a manner that appears at least tongue-in-cheek, if not directly critical. Its pioneer figure, described in rough black lines, is sandwiched between two more modern sections of geometric black and white stripes. The juxtaposition set up by this arrangement is ostensibly between old and new, traditional and modern, outmoded and progressive, though it is not immediately apparent with which category we are supposed to identify the four Ferus artists. Where the poster frames them as ‘studs’, it also draws a parallel between this status, the avant-garde abstraction suggested by the striped sections, and the figure of the pioneer, undercutting any suggestion that the contemporary stands in opposition to, or supersedes, the historical.

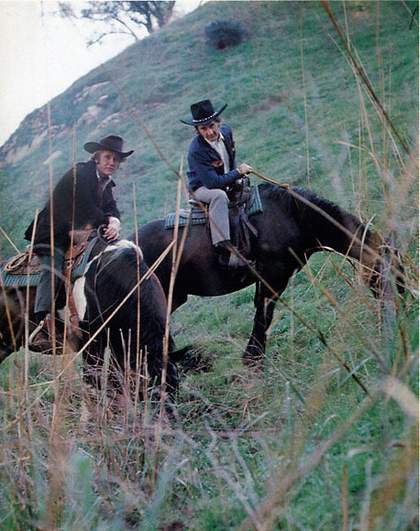

Fig.2

Jerry McMillan

Joe Goode and Ed Ruscha on Horseback 1968

Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica

Photo © Jerry McMillan

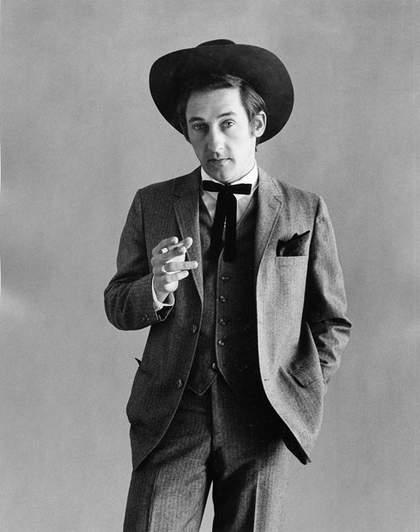

Fig.3

Jerry McMillan

Ed Ruscha as a Cowboy 1970

Photo © Jerry McMillan

Fig.4

Dennis Hopper

John Wayne, left, and Dean Martin, right, on the set of The Sons of Katie Elder 1962

University of Southern California, Los Angeles

Photo © Dennis Hopper

In her book Pop L.A.: Art and the City in the 1960s, art historian Cécile Whiting notes the tendency of those artists associated with the Ferus Gallery ‘to imagine themselves as a new type of regionally specific artist … as artist studs roaming the urban range’.14 Indeed, the image of the male artist as an outdoorsman appears in several other instances of self-fashioning produced by Los Angeles artists in the 1960s, including Ed Ruscha and Joe Goode’s cowboy posturing in a 1968 photograph taken by Jerry McMillan (fig.2) and a further 1970 portrait of Ruscha dressed as a cowboy (fig.3). Such images may, on one level, be intended as light-hearted parodies of the 1966 California gubernatorial campaign images that depicted candidate Ronald Reagan posing in a cowboy hat on horseback, set against a dramatic rocky backdrop. They may also have reminded Ruscha, Goode and McMillan of a photograph of Hollywood stars Dean Martin and John Wayne on horseback, shot in 1962 by Dennis Hopper on the set of Hollywood western The Sons of Katie Elder (fig.4). Hopper’s status as both a film actor and a member of Los Angeles’s avant-garde art scene indicates another useful context for images of artists as cowboys: as Neil Campbell has explained, Hopper’s films, including Easy Rider (1969) and The Last Movie (1971), indicate a critical approach to westerns, one characterised by ‘an urgent need to see the genre differently, moving beyond it or sitting disruptively “beside” it, willing to reflect on its inner workings, ideological nuances, and generic use of action, images, and character’.15 In Easy Rider, Hopper’s bikers, Wyatt and Billy, ride through the vast landscape of their Old West namesakes, in search of America, a clear embodiment of the cowboy cult reimagined for a disillusioned post-war generation. For Campbell, they find corollaries in Andy Warhol’s Double Elvis 1963 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) or Roy Lichtenstein’s Fastest Gun 1963 (private collection), in which pop art renditions of gunslingers serve ‘to defamiliarize and interrogate the associated cultural and political violence prominent in the mid-1960s both at home and abroad’.16 Ruscha and Goode offer parallels closer to Hollywood’s home. Their images are attuned not only to the national and geopolitical context, but also to the fraught role that regionalism played in a fledgling cultural city.

Fig.5

Ed Ruscha

Standard Station with 10-Cent Western Being Torn in Half 1964

Private collection, on extended loan to The Modern, Fort Worth

© Ed Ruscha

Fig.6

Ed Ruscha

Cheap Western Study 1962

Private collection

© Ed Ruscha

Fig.7

Ed Ruscha

Torn Western Study 1963

Private collection

© Ed Ruscha

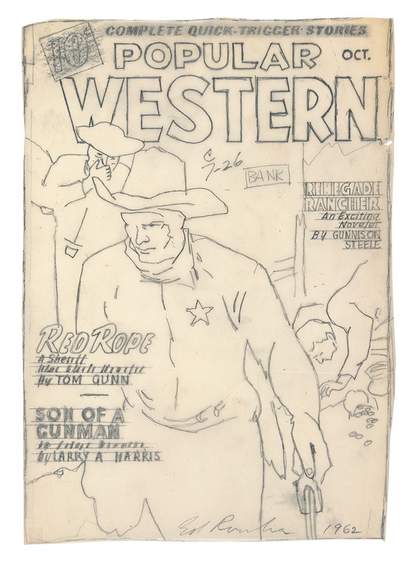

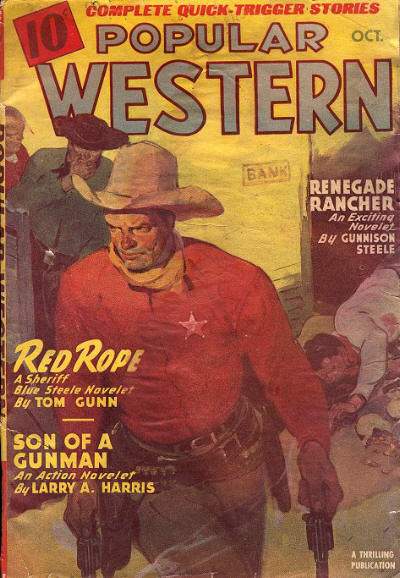

Fig.8

Popular Western, vol.31, no.2, October 1946

© Better Publications, Inc.

Ruscha’s own interest in the western as a popular cultural genre is suggested by several works from the 1960s: painted depictions of pulp western comic books appear in Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western 1963 (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) and Standard Station with Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half 1964 (fig.5), the latter of which curator Karin Breuer has read as an assertion of the obsolescence of the Old West in the face of the new and heroic automotive landscape of the gas station.17 Studies for both paintings reveal that Ruscha traced their outlines from an actual comic book cover using pencil on tracing paper, depicting them both whole and torn almost in half (figs.6 and 7). These examples suggest that for Ruscha, the attraction lay in part at least in the vernacular nature and cheap availability of the comic book western (costing only ten cents) and its materiality (as interesting torn as in pristine condition). Later works, such as Western with Fly 1967 (private collection) and Western, with Two Marbles 1969 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo), depict the word ‘western’ as if constituted out of ribbons of paper and pools of liquid respectively, indicating that he may also have found the word itself intriguing as a concrete form.18 Certainly, however, the symbolic potential of the cowboy also appealed. In Ruscha’s graphic treatment of Popular Western’s cover image, the figure of the gun-wielding Sheriff Blue Steele is carefully demarcated in pencil outline in one drawing, then shown ripped apart in the second. This act of tearing, and the transition from the detailed tracing of the first image to the vaguer and more sketchy version of the second, might indicate an ambivalence towards the contemporary power of this iconic figure and quintessential ‘American’ hero. That the issue in question (fig.8) dates from October 1946, when Ruscha was just twelve years old, also suggests a self-conscious continuity between youthful play-acting and adult self-fashioning.

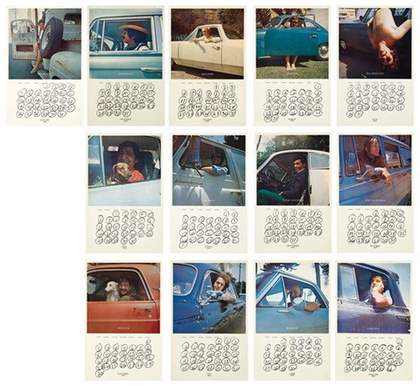

Fig.9

Joe Goode

L.A. Artists in Their Cars calendar pages, 1969–70

© Joe Goode

Such references to the Old West and the characters that inhabit it are inevitably situated within the context of post-war citation of the history and mythology of the frontier, and the countercultural interrogation of the ideologies that they contain. The widespread depiction of the cowboy and frontiersman by artists and filmmakers alike points to the value that the frontier held both for political discourse and for a city asserting its cultural identity, both played out against the backdrop of American national identity during the Cold War period.19 The portraits of Ruscha and Goode thus seem to oscillate between jokey and serious, like Easy Rider betraying an ambivalent position towards the historical West. Like contemporaneous depictions of other Ferus figures surfing (Ken Price), on motorcycles (Billy Al Bengston), in cars (the dozen men who make up Joe Goode’s L.A. Artists in Their Cars; fig.9), or surrounded by glamorous models aboard a gallery-branded boat (director Irving Blum), their cowboy posturing both confronts and performs the overt machismo of the Ferus stable of artists during the early 1960s, epitomised in labels such as the ‘Ferus gang’ or the ‘Cool School’.

Images of Ferus Gallery ‘cowboys’ and ‘frontiersmen’ invoked tenacity and hard graft in the midst of lawlessness, implying a cultural void to be conquered and settled by pioneering artists. Furthermore, just as the cowboys depicted in these popular cultural outputs were almost exclusively white men, so too were the artists of the Ferus stable. These kinds of performative photographs thus also reflect the starkly gendered and racialising terms according to which frontier and Old West narratives were deployed during the Cold War. Historian K.A. Cuordileone has described the period in terms of a widespread cultural and political crisis of (white) masculinity and reactionary performative bravado epitomised by John F. Kennedy’s ‘New Frontier’.20 The ‘cult of toughness’ that Cuordileone identifies in the Kennedy administration might also serve as a description of the macho swagger that many have observed among the Ferus Gallery artists, who performed the rhetoric of American manifest destiny even as they resisted the conservative restrictions of American suburban life that predominated in and around Los Angeles. While L.A. Artists in Their Cars seems less obviously connected to the visual vocabulary of the frontier and the Wild West and arguably posits leisure, rather than labour, as the artist’s primary mode of activity, it nonetheless establishes a correlative to artists on horseback via its emphasis on hegemonic white masculinity. It also suggests the easy manner in which the rhetoric of the frontier segued into that of car and beach culture.

Whereas Goode’s calendar half-ironically lauded car culture as an integral part of West Coast artistic identity, the 1971 exhibition How The West Was Won, curated by artist Barbara T. Smith and motorcycle racer and fibreglasser Dick Kilgroe at the Fresno State College Art Gallery, drew more explicit links between contemporary custom car subcultures and the history and mythology of westward expansion. The exhibition’s premise was that works by artists such as Billy Al Bengston, DeWain Valentine and others shared a common sensibility with the creations of professional autobody decorators ‘Von Dutch’ Holland, Dean Jeffries and Rollin ‘Molly’ Sanders, in that they embodied ‘the spirit and need for adventure and exploration in the form of a vehicle, actual motion coupled with personal self-expression, singularity and style’.21 This sensibility, the curators argued, was particular to the region, where there was a unique crossover between the roles of professional autobody decorator and fine artist: ‘Here where we know there can be no further westward expansion into uncharted lands is the conflict most keenly felt’.22 The 1962 film from which the exhibition took its name charted several stages of westward movement, including the Gold Rush, the Civil War and the building of the railways; Smith and Kilgroe’s exhibition argued for motorcycle and custom car subcultures as the next historical step in that narrative.23

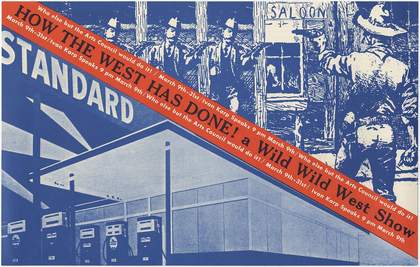

Fig.10

Ed Ruscha

Exhibition announcement for How The West Has Done! A Wild Wild West Show, 1966

Audrey Sabol papers, 1962–1967, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Fig.11

Poster for How The West Was Won, curated by Barbara T. Smith and Dick Kilgroe, Fresno State College Art Gallery, Fresno, 1971

Betty Asher papers, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

This was not the first time that the film’s name had inspired an exhibition of contemporary California art. In 1966 the Arts Council, a volunteer organisation sponsored by the Young Men’s/Women’s Hebrew Association of Philadelphia, had mounted an exhibition called How The West Has Done! A Wild Wild West Show.24 It was curated by Audrey Sabol with help from Ed Ruscha, who also designed an exhibition announcement that juxtaposed a reproduction of one of his gas station paintings with a woodcut-style image of a Wild West shoot-out (fig.10). Ruscha and Goode were both included in the show. In the same vein, the poster produced for the opening and after-party of Smith’s exhibition (fig.11) again suggests a correlation between the figure of the artist and that of the frontier dweller, in its depiction of two cowboys galloping away from each other but on conjoined horses, rendered in the vivid blue, red and purple tones more readily associated with the custom car aesthetic. The text, which reads, ‘Round up the deputies… We’ll head the outlaws off at the pass… then – we’ll divide up the payroll…’ playfully emphasises the historical referent, though leaves it unclear whether we are to identify the artists with the sheriff’s party, or the outlaws.

These examples express the different levels of seriousness or playful irony with which artists, photographers and curators were staging the American West as a crucial contemporary concern. Whether via description, performance or confrontation, they were responding to a set of pervasive clichés with which both the Los Angeles art world and the work produced within it were discussed by critics at the time, and which echo the structural symmetries upon which Terry Smith remarked over a decade later. Art criticism of the 1950s and 1960s – not only that produced by New York-based writers such as Barbara Rose but also by her West Coast counterparts Henry Seldis, Arthur Millier, Jules Langsner and Henry Hopkins – resorted frequently to regional stereotype in their descriptions of the city’s art scene and the work that emerged from it: the Los Angeles art world was ‘small, embryonic, and self-contained’ according to Rose;25 it was located, said Langsner, ‘at the end of a transmission belt moving from Paris to New York to Los Angeles’.26 If the region was characterised by its far-flung geography, warm climate and rugged topography, then these also were established as influences on the city’s contemporary cultural production. Thus, according to Millier, writing in Art in America in 1954, ‘A near-desert climate and its scattered physical makeup apparently influence the city’s art. Artists seem unconsciously to reflect the warm climate in a preference for warm colors’.27 In an essay in that same issue of Art in America, Seldis framed this state of affairs in more romantic terms that tally with those highlighted by Alloway, concluding that recent works by West Coast artists ‘evoke a sense of contemplation, peacefulness and freedom which may be attributed to local climatic conditions … The influence of the West’s wide open spaces and man’s inescapable intimacy with nature is reflected in much of West Coast art’.28 At the 1963 California Conference on the Cultural Arts held at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), the Director of the Pasadena Art Museum, Thomas Leavitt, uncritically reiterated those tropes in his statement that ‘California’s healthful cultural climate has enabled the visual arts to prosper here’.29

Such characterisations of Los Angeles art, whether intended as critical or supportive, served to define and assert the kinds of cultural hierarchies that Terry Smith critiques in ‘The Provincialism Problem’. To some historians they have provided argument enough for the recuperation of the city and the region as a significant site of important cultural production, the history of which has nonetheless been ignored in histories of American art. For example, provincialising art criticism such as Rose’s or Seldis’s served as a rallying cry for historians, archivists and curators working towards the first iteration of the Getty-led Pacific Standard Time initiative, which focused on art in Los Angeles and which culminated in 2011. However, straightforward art-historical recuperation can run the risk of ignoring artists’ own engagement with precisely those provincialising mechanisms that are perceived to have excluded them. As we have seen, many deliberately adopted the provincial position in a manner that might be read in terms of performance or parody. Often they did so via knowing reference to the longer history of the discourse of provincialism.

Art criticism and boosterism

That post-war critical tropes emphasising Los Angeles’s topography, climate or lifestyle of leisure were predicated on a longer history of regional myth-making is widely acknowledged, as is the iterative self-invention that has characterised the city’s history, both in actuality and in the popular imaginary.30 The rhetoric deployed by Rose and others echoed one of the nation’s most significant historical regimes of symbolic meaning-production, boosterism, which historian Tom Zimmerman has called ‘the most efficient and multi-faceted … promotional campaign in American history’.31 Between the 1870s and the late 1920s, boosterism was mobilised as a means of expanding the population, size and wealth of the city via a sustained and hugely successful campaign of place-making and publicity. Its stakeholders were varied but united by a clear vested interest; they included the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, the Los Angeles Times, the L.A. Realty Board, Southern Pacific Railroad, Automobile Club of Southern California, Municipal Art Commission and the California Fruit Growers Exchange, who coordinated the Sunkist marketing campaign. The Chamber of Commerce assembled a collection of over 50,000 stock photographs illustrating the multiple charms of the southern California life. Publications such as Land of Sunshine (founded in 1894 and later titled Out West), Southern California: Year-Round Vacationland Supreme and Southern California All The Year provided readers in the Midwest and Northeast of the United States with depictions of the perfect climate and abundance of agriculture, the romanticisation of California’s mission history, and narratives of the Hollywood real estate boom. Land of Sunshine even included a pull-out postcard that could be sent to friends and family back home along with a subscription to the magazine. Promotional materials emphasised southern California’s warm, dry climate, which offered the promise of health cures for late nineteenth-century consumptives, outdoor leisure pursuits for twentieth-century tourists, and plentiful employment, cheap and fertile land, and improved housing standards for would-be migrants during all decades.32 As historian Lawrence Culver has noted, the myth of the frontier as a land of opportunity for white Americans played a central role in the construction of this idealised vision of the American West, even into the twentieth century.33 As early as the nineteenth century, the imagery of sun-drenched leisure and that of hardworking pioneer spirit were intertwined via the imperatives of boosterism.

Fig.12

Judy Chicago

Rainbow Pickett 1965, 2004

Collection of David and Diane Waldman, Waldman Family Trust, Rancho Mirage, California

© Judy Chicago

Photo © Donald Woodman

Though some decades separate the era of boosterism and the development of the post-war art scene in Los Angeles, the two both represent a sustained and self-conscious attempt to create the city. Moreover, they both rely on an appeal to the American cultural imaginary to do so. In the hands of Barbara Rose and others, however, the intent of mobilising boosterist rhetoric is reversed: the idyllic ease of life championed by the boosterists is offered as evidence of superficiality and triviality. For Rose in 1966 and for Peter Plagens in 1974, Los Angeles and California more generally were just too pleasant to produce serious or noteworthy art. ‘America’s greatest art center (New York) has been ugliest longest’, opined Plagens in the introduction to his book Sunshine Muse: Art on the West Coast, echoing Rose’s infamous assertion in the dismissively titled article ‘Los Angeles: The Second City’ that ‘the brilliantly sunny, palm-studded, DayGlo-spangled Los Angeles landscape inspires an art quite different from that made in reaction to New York’s frigid lofts and littered slums’.34 Doubtless Rose had in mind the reflective and often brightly coloured plastic sculptures produced by artists such as Craig Kauffman, Helen Pashgian, Peter Alexander, Fred Eversley and even Michael Asher, works that spawned the reductive label Finish Fetish (or Fetish Finish as it was sometimes deployed).35 But her words also invoke those older boosterist tropes. We might even read echoes of the visual vocabulary of boosterism in Plagens’s dismissal of Judy Chicago’s minimalist sculpture Rainbow Pickett (fig.12) as ‘fruity’ despite its inclusion in the landmark 1965 exhibition Primary Structures in New York.36

Thus the very terms deployed by boosterists to assert Los Angeles’s superiority – and thus increase its profile and ultimately its competitiveness as a city with national import and influence – were turned against the city’s art world in order to emphasise its failure to achieve that goal. That is, if the primary aim of boosterism was to transform Los Angeles from an insignificant frontier town, post-war art critics were on hand to remind the city that it remained just that, at least in cultural terms. The potential for the frontier to serve in both positive and negative critical terms highlights the tension between its delimitation of a geographic location and its operation as both metaphor and origin myth, one that retained its potency in the post-war decade. Drawing on the terms set out by Miwon Kwon (albeit in relation to different artists and practices), the frontier operated for post-war artists and critics as at once a location-bound site and one defined by discourse.37 It was as much to this discourse of regionalism that Los Angeles artists were responding, as to the specific topography of their home state.

The complex and often contradictory political-cultural value of frontier rhetoric in the post-war and Cold War period is indicated in its frequent deployment not only by art critics seeking to provincialise California, but also by those seeking to assert the region’s singular cultural status. Frontier was the name chosen by Gifford Phillips when in 1949 he founded what he later described as ‘a politically-oriented journal covering the Western states’.38 Subtitled The Voice of the New West, the magazine was conceived partly in response to the political and cultural conservatism of the Los Angeles Times; Frontier’s art critic Gerald Nordland (who joined in 1956) was perceived in direct contrast to the Times’s conservative critic Henry Seldis. Frontier took as its editorial inspiration the liberal politics of the Nation and New Republic, though refocused towards ‘a regional perspective and readership’.39 Phillips was not inexperienced in producing regional publications: he had briefly been in charge of the Colorado-based publication Rocky Mountain Life, and brought its editor Phil Kerby on board for Frontier. But while Phillips expressed frustration with Rocky Mountain Life’s ‘mishmash of mountain tales’, he envisioned a more robust role for his new California publication. In developing it, he drew on the advice of liberal journalist Carey McWilliams, author of Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California (1935), Southern California: An Island on the Land (1946) and California: The Great Exception (1949).40 The new title, decided unanimously and intended to suggest ‘an exploration of new political territory’, invoked the loaded history of westward expansion.41

Asserting a specifically southern Californian cultural agenda was part of the project of Frontier from the beginning, while the magazine acknowledged the asymmetrical power relationship between West and East, with New York ‘widely regarded as the de facto arts capital’ in relation to southern California, the art of which lacked, in Phillips’s estimation, the critical cachet of New York.42 ‘In Eastern cultural circles,’ Phillips observed, ‘Los Angeles was seen as a rather barbaric place, its culture a bizarre mix of Hollywood and off-the-wall cultism.’43 Phillips’s assessment of the cultural and critical hierarchies that advanced the position of New York over Los Angeles were shaped by the specificity of California in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when the city had little or no cultural infrastructure and a political environment hostile to modern art.44 In many ways, then, Frontier is a product of its time and place. But it also participates in a longer and more wide-reaching narrative that frames art and art criticism in the middle of the twentieth century in terms of the much older, more pervasive and strongly contested rhetoric of the frontier, one in which boosterism is complicit. And, as Smith’s 1974 article indicates, it was predicated on assumptions that would persist. Phillips’s pioneers were politically liberal and culturally adventurous; they were also, like their forebears, precisely geographically located: ‘Frontier,’ he wrote, ‘is … especially designed for the pioneers of today, and for everybody who wants, above all, to create a mighty, new society in the West.’45

If the frontier held symbolic potential for those, like Phillips, who sought to delineate a specifically regional cultural agenda, then it was also mobilised to describe American art as a national phenomenon. As critic Brian O’Doherty noted in 1973, the model of the frontier (along with the personas of the colonial pioneer and the native that it implies) has a significant presence in American cultural and historical criticism, from literary critic Philip Rahv’s dubious typology of American writers in the 1939 essay ‘Paleface and Redskin’ to Harold Rosenberg’s 1954 essay ‘Parable of American Painting’ (originally titled ‘A Fable for American Painters’ and retitled for publication in Art News).46 In his essay, Rosenberg draws a distinction between European and American artists as falling into the categories of ‘Redcoatism’ and ‘Coonskinnism’, which are terms he derives from school history accounts of a British military expedition that was ambushed in unfamiliar territory in Ohio in 1755. The British preference for formation fighting was no match for the frontier skirmish tactics adopted by the American colonials, and the redcoats suffered painful losses. For Rosenberg, the episode offers an analogy for American painting: the old-guard painters, encumbered by European tradition, are no match for their younger counterparts, who are unhindered by conventional academic training. Unfettered by the dictates of education, the latter are free to respond to new and unfamiliar terrain. Pioneer ignorance, located ‘in the blinking wilderness’, is productive and progressive. ‘The triumphs of individuals have been achieved against the prevailing style or apart from it, rather than within or through it.’47 The single, but crucial, difficulty facing the redcoats and European academic artists alike, was the fact of being in the wrong place. Location defines temperament.

Underpinning both Gifford’s magazine project and Rosenberg’s peculiar parable is the mythos of the American West. It is appropriated for modern American art via the model of Frederick Jackson Turner’s ‘Frontier Thesis’, according to which American democracy is presented as the outcome of the determined labour of the pioneer at the frontier (a model of American advancement that relies explicitly – and of course problematically – on the perceived emptiness and free availability of the land in question).48 In his magazine’s inaugural editorial, Phillips articulated what he saw as the radical potential of the frontier as both position and method, writing that ‘this new frontier no longer involves large unexplored tracts of land. Its undiscovered areas lie in the realm of the mental, moral, and social – rather than in the physical’.49

The frontier as site

How are we to read the Ferus Gallery’s Studs poster, and those other references to similar frontier personas, in light of this widespread frontier discourse that at once delimited the regional and sought to define the national? That the frontier remained a contested term in the post-war decades – one that simultaneously divided the category of American art while uniting against Europe – suggests that the works I described above should not be taken merely as examples of regressive and culturally bereft hinterlands. Or, at least, following Rosenberg’s formulation, their emphasis on manual labour and common sense over and above regimented academic education renders them more successful than their disciplined but inflexible enemy (the latter indicated, perhaps, by the rigid stripes that surround our intrepid pioneer). They confound expectations of hierarchy, as manifested in the common centre-versus-periphery comparison. In the Studs poster, the frontier and the activities that it implies are deployed to articulate a set of cultural contradictions: between art world insider and provincial outsider, between national heartland and cultural periphery, between provincialism as a location and as a mindset (or, following Rosenberg’s military analogy, tactic). In this sense, Los Angeles art conforms to Smith’s observation that provincial art can be ‘highly self-conscious’.50 In this case, however, that self-consciousness assumes a deliberate and semi-ironic inhabiting of the provincial position. Like the post-western critique of the western myth and the associated collective fictions of the frontier model, such practices must surely be read as somewhat critically engaged and heavily invested in irony.

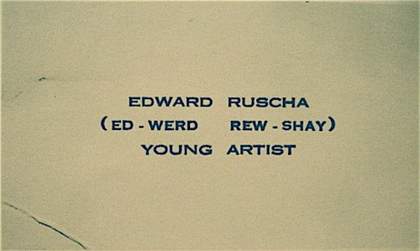

Fig.13

Ed Ruscha

Business Card 1960s

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

© Ed Ruscha

While the Studs poster articulates this set of contradictions explicitly via the appropriation of the visual vocabulary of the frontier, we find a similar indication of Los Angeles artists’ self-conscious negotiation of the ‘provincialism problem’ manifested in more conceptual formats too. For example, we might read Ed Ruscha’s tongue-in-cheek business card (fig.13) as performing provincialism in its assertion of youth and its implication of lack of renown (that the artist is not well enough known that a reader would be expected to know how to pronounce his name). Ruscha’s adoption of the pseudonym Eddie Russia played on the tendency of strangers to mis-pronounce his name as well as the note of suspicion that its apparent foreignness might engender in the Cold War United States. The inclusion on his business card of a pronunciation guide also points to Ruscha’s doubly othered status, not only as a Los Angeles artist, but also as the descendent of Bohemian/German immigrants. Indeed, his self-deprecating acknowledgement of the difficulty presented by his name reads doubly ironically in light of the fact that his grandfather changed it from Ruiska upon emigrating. Thus we might read Ruscha’s business card as a performance of his own provincialism as well as that of the art scene of which he was part, one that was still emerging in 1963 (and, one might add, one in which Ruscha was in some sense an outsider anyway, coming as he did from Oklahoma).

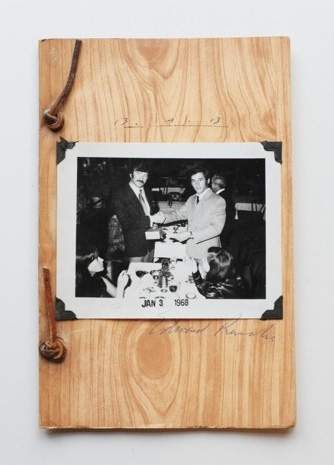

Fig.14

Ed Ruscha and Billy Al Bengston

Business Cards 1968

Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago

© Ed Ruscha and Billy Al Bengston

Anxieties about the new professionalism that Los Angeles’ burgeoning art scene might demand are evident – albeit in a tongue-in-cheek way – in Ruscha’s 1968 collaboration with Billy Al Bengston on the artists’ book Business Cards (fig.14), in which the two perform an elaborate ritual of creating and exchanging business cards wearing conventional grey-suited office attire and mock-serious expressions. As art historian Monica Steinberg has noted, the book, which chronicled the project of devising, producing and exchanging the cards, represented an acknowledgment of the tendency towards roleplay in the worlds of business and art alike.51 For Steinberg, the hyperbolic play-acting that Bengston and Ruscha enact is incongruous, highlighting as it does the chasm between a public image ‘more closely associated with the sun, sand, and surf lifestyle of Los Angeles’ and the professional world of serious business.52 While the latter represents the grown-up world of the symbolic order, then the former is implicitly infantilising, despite the origins of such myths in the economic imperatives of boosterism.

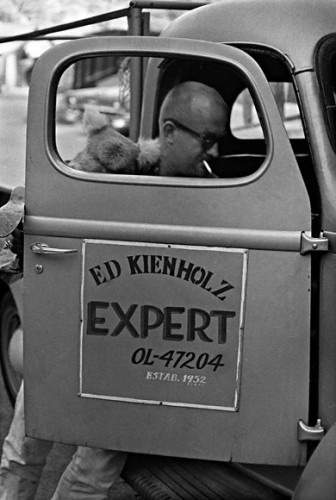

Fig.15

Marvin Silver

Edward Kienholz 1958

Marvin Silver and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica

© Marvin Silver

If Business Cards humorously performed the entrée into privileged circles and thus permitted the transition from provincial to insider, then a similar play on the relative status of professional and amateur underpins Ed Kienholz’s self-styled persona, according to which the jack-of-all-trades status implied by the artist’s pick-up truck was belied by the label ‘expert’ on its side (fig.15). Kienholz cultivated an overtly masculine persona and also gained a reputation as a barterer. ‘If he had something,’ fellow assemblage artist Gordon Wagner explained, ‘if he had a piece – I’ll trade you for a typewriter. I’ll trade you for a lawnmower, a drill press, a motorcycle. He’d trade anything.’53 On one level, the laconic performance of masculine labour in evidence in the photograph of Kienholz echoes art historian Caroline Jones’s assessment of the self-fashioning of other American artists of the 1960s, in particular their emphasis on masculinist rhetoric that equated the labour of the artist with that of the welder, factory worker or technician.54 In its allusion to the individualist labour of making do, Kienholz’s persona both emphasises the economic precarity of the Los Angeles art world – where a work of art had as much value as a drill – and recalled in clearly gendered terms the hard manual graft of the pioneer. It also embodied the swagger of the cowboy, though with how much irony is not entirely clear. This performance of provincialism via the framework of professionalism and its absence also informs Ruscha’s 1964 Artforum advertisement publicising the rejection of his book TwentySix Gasoline Stations from the Library of Congress. It serves as a reminder of his outsider status (even as his listing of its sale in venues in Los Angeles and New York situates the artist in both places at once). Ruscha’s dance around the borders of acceptance and rejection, inside and out, centre and periphery, are complex and continual: while the Library of Congress represents establishment acceptance, the assertion of his rebel status in the pages of America’s most up-and-coming new contemporary art magazine (one founded on the West Coast and later moved to New York) arguably represents the kind of Coonskinnism that Rosenberg described, reinforced by the renegade posture that Ruscha would adopt when he dressed up as a cowboy.

Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 account of the frontier was simultaneously an articulation of its closure. Seventy years later, at the end of his essay ‘Whatever Happened to the Frontier?’, Lawrence Alloway similarly comes to the conclusion that the frontier is a thing of the past. ‘The American frontier,’ he writes, ‘got eroded by the same internationalism and by the same communications revolution that exploded national boundaries in the art of Europe.’55 Yet the symbolic potency of the frontier narrative remained urgent in the post-war decades; the allegory of the frontier deployed provincialism at a local level but against the geopolitical backdrop of Cold War geospatial politics. For urban planning historian William Fulton, the development of Los Angeles, a city whose history is rooted in land development and regional marketing, also represents a continuation of the frontier in the ideological form of suburban expansion.56 In these dual contexts, the growth and internationalisation of the Los Angeles art world resulted not in the disappearance of the frontier and all it stood for, nor the dissolving of provincialism, but an even more urgent need to find ways to navigate both. Artists in this new version of the American West did not straightforwardly position themselves in opposition to the perceived cultural centre of New York, as is quite often implied in both history and criticism. Rather they performed the problem of provincialism in order to articulate the complex histories within which it was embedded and the multiple contradictions according to which it was structured. This geographical specificity permits a reading of art criticism through the lens of the West’s longer cultural identity, one shaped by the visual clichés of boosterism and implicated in the structural metaphor of the frontier as it pertains to conceptions of American manifest destiny. As such, of course, the model of the frontier is not confined to California (indeed historically it is primarily located elsewhere, as the specifics of Rosenberg’s battle citation attest). Rather it emphasises the way in which Los Angeles’s cultural identity is to some extent predicated on a broader identification with the position of the regional or the provincial.

At the heart of the provincialism model is the notion of place as practiced, a notion derived from the work of cultural theorist Michel de Certeau that informs much writing on critical site-specific art and institutional critique.57 Although the works that I have described do not fit easily into those categories as they are conventionally delimited, there are some useful points of comparison. Among others, Nick Kaye and Miwon Kwon challenge the ideas of a site’s fixity, instead proposing it as mobile, unstable or elusive. As Kaye describes it in Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place and Documentation, site is ‘always in a process of appearance or disappearance’.58 The frontier is exemplary of such unfixity. It is a physically mobile site always defined in relation to other places, and one that has engendered a similarly mobile set of meanings and associations. Yet it is its lack of fixedness that grants it its enduring power, allowing it to become a shifting signifier that can be deployed according to sometimes contradictory agendas. Kwon, writing in One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity, articulates the tension between identity as a localised procedure ‘bound to the physical actualities of a place’ and the kind of internationalising tendencies of contemporary art and its economies that might be discerned with particular clarity in the burgeoning Los Angeles art scene of the 1960s.59 For Kwon, the relation to site must always be ambivalent, especially when it is expressed in the literal and conceptual expansiveness of the art world: ‘If the search for place-bound identity in an undifferentiated sea of abstract, homogenized, and fragmented space of late capitalism is one characteristic of the postmodern condition,’ she writes, ‘then the expanded efforts to rethink the specificity of the art-site relationship can be viewed as both a compensatory symptom and a critical resistance to such conditions’.60 The practices that I have described above are thus site-specific not because they reflect the warm climate and open spaces of southern California, nor merely because they refer directly or indirectly to the peculiarities of the American West (whether historically via the rhetoric of the frontier, or in contemporary terms via allusions to California subcultures or lifestyle). First and foremost, they relate to the discursive site of provincialism, according to which the space of the West (as both landscape and myth) was mobilised during the post-war period, either as a means of denigration or as an assertion of productive marginality. In doing so, they drew attention to the ways in which this discursive space deployed assumptions about physical location as a means of reinforcing the centre-periphery dynamics of the post-war art world.

Ruscha, Goode and Smith, among others, recognised the relational constitution of regionalism as signifying both physical location and cultural discourse. They performed a deliberately constructed regional identity in order to emphasise that regionalism is contingent both on assumptions about the power of contemporary cultural centres, and on specific histories of the West. The iconographies of both boosterism and the Old West were potent in this context precisely because, though rooted in history, they were always imbricated in myth, fiction or fantasy.61 In performing provincial personas that are demonstrably and often hyperbolically masculine, the examples of self-fashioning that I have discussed also reveal the gendered manner in which regionalism operates, according to which the West is constructed as a space of (masculine) manual labour, even as Los Angeles is feminised on account of its perceived inexperience, triviality and superficiality.62 In performing the complexities and contradictions of regionalism or provincialism, they stop short of reiterating a centre-periphery model via the mode of oppositionality, instead occupying a self-consciously ambivalent position. Their subject, then, is not Los Angeles or California per se, but the very idea of place as an artistic category or the determinant of cultural import. They play on the binary dynamics of provincialism, but refuse to conform to the oppositional methodologies that the centre-periphery model implies, instead inhabiting a ‘both-and’ position. They present the regional as a shifting signifier onto which is projected multiple, sometimes conflicting, desires that speak to a longer history of American identity construction that continues to structure the American cultural imaginary in the context of contemporary art.