In 1968 the artist Nam June Paik arrived at the studios of WGBH-TV in Boston. During the years that followed, he developed a body of work at the station that subverted all conventions of public television. Eschewing traditional formats, his programmes were hallucinatory collages of abstract, electronic images interwoven with footage of avant-garde performances and references to pop culture, often framed by dry voiceover narration. Considering that WGBH was the site of many ‘firsts’ for Paik – including his first production for broadcast and the invention of his video synthesiser – it is surprising that little scholarship has been produced on this strand of his work.1 This paper draws from unpublished archival documents and conversations with the station’s producers to provide a fuller picture of Paik’s engagement with WGBH. Addressing the whole of Paik’s work there, with particular focus on his most ambitious project – the four-hour Video Commune 1970 – it shows how Paik sought to reconcile the artistic aims he had been articulating in other media with the distinct nature of broadcast television.

Broadcasting forced Paik to confront the question of audience in a completely new way. In contrast with the audiences at the performance festivals and gallery exhibitions to which he had previously been accustomed, television audiences were anonymous, geographically dispersed, and, as they were likely watching from home, susceptible to a range of distractions. In a 1972 letter to John Cage, Paik explained, ‘TV is … a form of giving away… even more so than music. TV: You give away through airwave… you don’t even know, to whom it went.’2 His productions for WGBH show how his thinking about this unknown audience evolved over time. Paik came to realise that, while television could not easily accommodate the physical participation he had invited in his sculptures, what it could do is disseminate ideas to a broad audience and unsettle habitual ways of thinking. The work Paik produced for the station reveals how he moved from efforts to achieve direct participation to programmes that present a more expansive understanding of audience engagement, with the crux of this shift occurring in 1970. While recovering understudied work by a major video artist, this paper also sheds light on post-war artists’ shifting ideas about the value of viewer participation and the potential of technology’s global reach.

Paik arrives in Boston

Paik came to WGBH four years after his move from Germany to New York City. There, he had been exhibiting his work at the upstart Galeria Bonino when the gallerist Howard Wise – a promoter of kinetic, light and electronic art – included his work in a 1967 group show, Lights in Orbit. In 1968, as Wise was organising another show, TV as a Creative Medium, he met a group of producers from the Ford Foundation’s recently established Public Broadcasting Laboratory who were embarking on an initiative to enlist artists to collaborate with public television. The group selected six artists, including Paik, to take part in a pilot programme. They found an ideal partner in WGBH, which had a growing reputation as a hub for experimental television.

By the time he reached Boston, Paik had been working with television for several years, having debuted television-based artworks in his first solo show, Exposition of Music – Electronic Television in Wuppertal, Germany, in 1963. There, he exhibited a dozen television sets whose inner workings he had modified to produce a range of effects – from twisting distortions of the picture signal, to abstract kinetic shapes and simple lines.3 In an essay, Paik explained that he intended these works to introduce ‘indeterminism and variability’ into visual art.4 He achieved this goal in three ways: by physically altering internal circuitry to distort broadcasts; by introducing external input – for example, by allowing audience members to speak into a microphone whose audio signals would alter the picture; and by relying on the sheer variability of broadcast television, allowing whatever happened to be playing to become part of his art. As the art historian Christine Mehring has noted, Paik was attracted to television at this early moment ‘not as a means of broadcasting and reaching out, but rather … as a way of creating electronic pictures’.5 That is, in his Wuppertal exhibition he took the inherent ability of television to transmit identical broadcasts to an extensive number of receivers and turned it on its head; his televisions, in effect, transformed these identical pictures into individualised distortions, viewable only within the space of the exhibition.

Paik continued along these lines in New York, where he further pursued the participatory potential of his altered sets. In 1966 he created another interactive piece in which audiences could speak into microphones to create new forms, this time on a colour set, calling it Participation TV.6 Three years later, Paik reused the title for a different work featured in Wise’s TV as a Creative Medium, a closed-circuit installation with three cameras that presented visitors with distorted images of their own faces. ‘Participation TV’, in these examples, refers variously to artworks that respond to voices or that incorporate live pictures of their viewers; Paik would return to the phrase in his broadcast work to refer to more conceptual forms of interactivity.

It was at this moment that Paik began to articulate the importance of audience participation as a mode of reducing the inherent passivity of television viewing, rather than simply as a source of indeterminacy. In a 1965 essay, he outlined a plan for the future development of an ‘adapter with dozens of possibilities’ that people could connect to their home televisions to modify or create pictures, transforming the medium ‘from a passive pastime to active creation’.7 In doing so, he voiced concerns about the potentially stultifying effects of television shared by a wide group of artists, addressed in such works as Richard Serra and Carlota Fay Schoolman’s later Television Delivers People 1973.8 These artists sought ways to ‘activate’ television viewers, in an attempt to counteract the advertising industry’s efforts to produce anesthetised, passive consumers.

As soon as portable video cameras became commercially available in the mid-1960s, Paik quickly adopted the medium, and showed his first video at the Greenwich Village nightclub Cafe Au Go Go on 4 October 1965.9 His early videos often featured recorded footage edited by the artist. Mayor Lindsay 1965, for example, shows a repeated loop of New York’s mayor, John Lindsay, waving to journalists; Paik manipulated the videotape, running electric current along its surface to produce static distortion that occasionally obliterates Lindsay’s face.10 Such videos demonstrate Paik’s continued interest in altering images through technological interventions into the medium.

At WGBH, Paik worked with director Fred Barzyk, a former theatre student and aficionado of the loosely structured, often participatory performance art events known as ‘happenings’. Barzyk was best known for the experimental programme What’s Happening, Mr. Silver?, which had attracted considerable media attention.11 He and colleagues David Atwood and Olivia Tappan collaborated with Paik and six other artists to produce The Medium is the Medium, a compendium of short videos which aired on 23 March 1969.12

Fig.1

Nam June Paik

Still from Electronic Opera #1 1969

Video, colour, sound

4 min, 45 sec

© Nam June Paik Estate

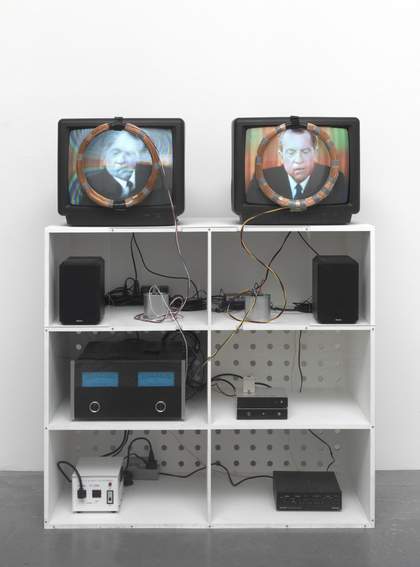

Fig.2

Nam June Paik

Nixon 1965–2002

Video, 2 monitors, black and white and colour, sound and magnetic coils

10 min, 51 sec

Tate T14339

© Nam June Paik Estate

Paik’s contribution – his very first foray into broadcasting – was Electronic Opera #1 1969, an engaging, five-minute video that is also a remarkably canny assessment of television’s limitations. The work combines several types of imagery, set to a soundtrack of classical music and voiceover narration to create a kind of avant-garde variety show. We first encounter purely abstract ‘dancing patterns’ – bouncing, rainbow-colored, slinky-like figures – taped directly from manipulated television sets that Paik had brought to the studio (fig.1). Next are three young men who gaze dazedly at the camera, their bodies solarised, and a nearly nude dancing woman, rendered in translucent coloured layers. A final element consists of taped television footage of Richard Nixon and his attorney general John Mitchell, their faces subject to swirling distortion. The disparate elements mesh together in a soft, electronic collage. Paik had worked with images of Nixon before, as in the video sculpture Nixon 1965–2002, in which magnetic rings attached to television monitors warp the president’s face (fig.2).

While its imagery generally conforms with Paik’s earlier sculptures and videos, Electronic Opera #1 also introduced new elements. For one, WGBH engineers helped Paik develop the ghostly, superimposed effects that he applied to the dancing figure, a technique he would return to again and again.13 Perhaps the most strikingly original aspect of the programme is the voiceover, which Paik recorded with staff announcer Ron Della Chiesa and Barzyk. Della Chiesa begins with a reference to Paik’s favourite title, saying, ‘This is participation TV. Please follow instructions.’ Paik then issues a series of short commands: ‘close your eyes’; ‘open your eyes’; ‘three-quarter close your eyes’; ‘two-thirds open your eyes’. At another point, Barzyk sighs and says that he is beginning to feel ‘awfully bored’; Paik responds, ‘thank God it’s the last one’, a reference to the video’s position as the last of the Medium segments. Barzyk then asks, ‘what do we do now?’ to which Paik replies, ‘let’s start it again’. The video recommences, until a voice abruptly instructs, ‘Turn off your television set’.

It is through these spoken lines that Paik communicates the challenges of working with broadcast television. The strategies he had previously employed in his altered television sets were no longer available; most obviously, there was no clear way to allow audience members to contribute physically to the production of images. Neither was there a way to gauge viewers’ interest in the programme or to make spontaneous changes. The voiceover ironises these difficulties. In it, Paik and Barzyk jump between speaking roles, assuming the positions of artist, audience and editor. In the spoken instructions, Paik invites viewers into a highly reduced experience of ‘participation TV’, one in which they can introduce minimal variability into the programme by looking, not looking, or partly looking at their screens. The complaints about boredom seem spoken by imagined viewers who have become annoyed with the programme. Finally, the call to ‘start it again’ implies that we are overhearing Paik and Barzyk in a live moment of editing, although the programme was pre-recorded. Electronic Opera #1 creates awareness of the different temporalities at stake in television: the distinct moments of recording, editing and watching that collapse into a general impression of immediacy under normal conditions. Set against a background of engaging visual effects, Paik’s voiceover self-reflexively exposes the mechanisms of television production.14

In his desire to transform television into ‘participation TV’ – from a one-way transmission to a two-way conversation – Paik entered a longstanding discourse around the nature of broadcasting. Whereas dialogue is often posited as the ideal mode of communication, radio and television developed historically along a dissemination-based, one-to-many model.15 As the poet and artist David Antin has written, the fundamental characteristic of broadcasting is the ‘the social relation between “sending” and “receiving”, which is profoundly unequal’, asymmetry is the norm and any attempts at interaction operate ‘in reaction to this norm’.16 In his early television work, Paik hoped to defy this structure and allow literal, physical intervention. Despite the ironic attitude towards viewer participation displayed in Electronic Opera #1, he continued his pursuit. His goal was to give audience members the ability to actively modify the appearance of televised images, along the lines of the adapter he had first imagined in 1965.

Video Commune: Beatles from Beginning to End

When Paik was able to stay at WGBH as artist-in-residence thanks to a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, he began to make the plans for this device a reality. He approached the station head, Michael Rice, and successfully petitioned him for funding to build a synthesiser that would make the creation of avant-garde television cheaper and more accessible. The synthesiser would incorporate elements from Paik’s modified televisions and participatory video installations; it would, in the artist’s words, ‘accumulate all my past experiments into one playable console’,17 effectively compressing ‘the whole studio into a piano keyboard’.18 As in his early sculptures, he imagined converting the television into something akin to a musical instrument, but now on an entirely new scale.

In 1969 Paik created the video 9/23: Experiments with David Atwood at WGBH. In it, he explored the kinds of image processing that could be carried out in a traditional studio setup and that he hoped to generate more cheaply with his proposed synthesiser. The project was never intended to air. It is weirder than his earlier and later work for the station; set to a space-age soundtrack of blooping electronic music and eerie distorted vocal sounds, it comprises pure abstraction, long shots of candles in a dark room, and distorted found footage, most notably the faces of Barzyk and associate producer Tappan. What Paik needed from these experiments, Barzyk recalls, ‘was to learn how to make these effects happen and what they were called. This was like learning a new language. He left with those images in his mind’s eye and tried to make them happen again with his low-cost synthesiser.’19 Paik showed the video in the groundbreaking 1970 exhibition Vision & Television at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University and would use excerpts from it in later broadcasts.20

Between 1969 and 1970 Paik travelled to Japan to construct his synthesiser with the engineer Shuya Abe.21 Atwood has described the machine as a ‘collection of cheap parts’, an assemblage of mixer-colour encoders, cameras, modified televisions and other components.22 The Paik-Abe Video Synthesiser could be controlled, but not precisely – it was tricky to replicate any effect exactly, and surprises were common. WGBH was known for its reliable, high-end production tools, and the synthesiser was thus in tension with the station’s spirit. As Paik would later say, ‘Ironically, a huge Machine (WGBH, Boston) helped me to create my antimachine machine.’23 The synthesiser made its first broadcast appearance in a live programme on the station’s sister channel, WGBX, on 1 August 1970.

Fig.3

Nam June Paik

Still from Video Commune: Beatles from Beginning to End 1970

Video, colour, sound

240 min

© Nam June Paik Estate

Titled Video Commune: Beatles from Beginning to End, the programme was Paik’s most ambitious project for WGBH: a sprawling, four-hour video collage set to the music of The Beatles. Over the course of the programme, Paik, other artists, and members of the public used the synthesiser to generate abstract patterns and distort live and pre-recorded footage. In the broadcast there were neon oscillations, fog-like masses of colour, and expanding target-like patterns; a translucent image of George Harrison’s face on a rotating turntable; engineers working inside the studio; and hands and bodies dematerialised into electronic blobs (fig.3).24 Then, every so often, the programme was suddenly interrupted by unedited Japanese musical performances and commercials. These clips are hardly noted in the literature on Paik’s work, which, when it discusses Video Commune at all, simply records it as the synthesiser’s debut. Yet it is this unexpected combination of the distorted clips and the unedited Japanese material which makes the piece especially intriguing. At the very moment that Paik introduced the synthesiser, a tool ultimately intended to allow broad audiences to modify televised images, he also began to move in a second direction: towards the introduction of what he would call ‘global television’.

As Video Commune opens, a narrator – Russell Connor, an artist and museum curator who would continue to assume this role in future Paik productions – gives a short introduction.25 He tells viewers to treat the programme like ‘electronic wallpaper’ to which they can tune in and out at any time, and then names six New England artists who will contribute to the piece.26 The bulk of the programme consists of these artists using the synthesiser to generate visual patterns, along with anonymous visitors to the studio who employ the tool. About an hour in, Connor’s voice returns: ‘Dear audience, this is participation TV. Your TV set is not there just to be watched passively, but to be played with actively.’ He then gives instructions to home viewers, explaining how they can modify the colour, brightness, and other aspects of the image using the knobs on their television sets – in effect hijacking controls meant to correct the picture and turning them into creative editing tools. In doing so, they would echo the participatory process they were seeing onscreen: in Connor’s words, they could ‘talk back to the synthesiser symbolically’. With these instructions, Paik provided a way for viewers to physically intervene in the apparatus to modify the artwork. Again, however, the extent of their participation would remain relatively constrained, limited to the modification of pre-existing images and visible only to themselves.27

Fig.4

Nam June Paik

Still from Video Commune: Beatles from Beginning to End 1970

Video, colour, sound

240 min

© Nam June Paik Estate

Amid these scenes of electronic image production and formal experimentations with colour and shape, it is jarring when the programme suddenly cuts to the sharp, highly produced Japanese material. For example, a long segment of scrolling horizontal lines set to ‘You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me’ cuts to a performance by the seven-year-old Osamu Minagawa, who sings while seated on a windowsill beside two dolls (fig.4). This is followed by two performances by stylish female singers and a Maggi soup commercial, all in the original Japanese. Connor, at the beginning of the video, explains the material’s inclusion: he says that Video Commune has been ‘expanded globally’ through a collaboration with the Osaka-based television station Mainichi Broadcasting System. To commemorate the world fair held in Osaka, Expo ’70, the station sent WGBH a compilation of Japan’s current hit songs, which also contained commercials. The commercials have been retained, Connor says, for ‘sociological and artistic reasons’.

Paik’s best-known statement on the international potential of television is his later, iconic video Global Groove 1973, which he produced for New York’s public television station, WNET. That video famously features tap-dancers performing to the American pop song ‘Devil with a Blue Dress On’, interspersed with performances by the Korean dancer-choreographer Sun Ock Lee; a ceremonial dance from an ethnographic video about Nigeria; a Japanese Pepsi commercial; and other material. It was three years earlier in Video Commune, however, that Paik incorporated international television clips into his video work for the first time. Indeed, the voiceover introduction to Global Groove, which describes the video as a glimpse into the expanded television channels of the future, clearly echoes the idea of global extension already presented in the earlier work. Paik’s notes and archival documents from the period leading up to Video Commune indicate that he intended the broadcast to serve, in part, as a statement on the social promise of television’s transnational reach.

In an undated typescript written before the broadcast, Paik outlined his plans. He envisioned that The Beatles’ music and synthesised images would ‘flow parallelly’, interwoven with images of people in the studio. Every so often, the synthesiser would need to be reconfigured to produce new types of visuals, a process that required it to be taken off air. During this time, Paik suggested, the pre-recorded Japanese material could be shown. In addition to providing a practical solution to the logistical difficulties of a live broadcast, the clips would serve a broader purpose: to ‘demonstrate the togetherness of mankind by showing successively two kinds of music from two kinds of continents’.28

The tone of the document suggests that Paik had encountered scepticism from WGBH executives regarding the Japanese clips, for reasons that remain unclear. In the document, Paik wrote that he had been developing the idea of ‘global television’ for a year, and insisted, in all capitals, ‘THERE IS ABSOLUTELY NO REASON TO COOL THIS SITUATION INTO APATHY ABOUT HARD WON GLOBAL TV’. The Japanese songs and commercials, he argued, must not only be shown but must also be interwoven with the American material. Showing the foreign footage alone ‘only amplifies the video nationalism currently prevailing in the international art world’, he wrote. Instead, ‘US and Japanese materials should be COMBINED and collaged and mixed and intefrated [sic] with each other. Otherwise, it is just self-defeating the purpose.’ It was not enough to simply broadcast the Japanese clips; it was essential that they collide and converse with the footage produced in Boston.

The conversation over the incorporation of Japanese clips in Video Commune relates thematically to Paik’s essay ‘“Global Groove” and the Video Common Market’, written in early 1970.29 The essay advocates for the free exchange of video across national borders, following the model of the European Common Market. Paik’s experiences in Boston clearly contributed to his thinking. For example, he attributed to David Atwood, the producer at WGBH, the idea that children are increasingly unfamiliar with the peaceful countries of the world – such as Switzerland and Norway – because television focuses so exclusively on conflict and violence. Were video more fairly distributed, he suggests, viewers could be exposed to a greater range and variety of global imagery that would contribute to mutual understanding. Paik concludes, ‘The American Public Television System is, by its nature, destined to be a vanguard for this movement. A persistent and protracted effort should be initiated by WGBH.’30 Correspondence indicates that the station took Paik’s proposal seriously; Howard Klein of the Rockefeller Foundation called the idea ‘most innovative’, noting that it will ‘attempt to create a first in international programming with the goal of bringing to watchers of television throughout the world greater understanding of their fellow man’.31 Paik likely intended Video Commune, which aired a week after Klein penned his letter, to constitute a first step in this direction.

Why, then, might Paik have chosen to debut the synthesiser and the global material in the same programme? The two types of footage, on the face of it, have little in common – one is experimental, process-based and participatory, while the other is a highly polished product of the pop culture industry. But their combination suggests Paik’s increasingly complex understanding of how broadcast television could most successfully engage its audience. In one sense, Video Commune furthers the artist’s aim of allowing viewers to exert increased control over the imagery they see, and thus disrupt the uniformity of a centralised broadcast. Yet Paik had clearly come to perceive that inviting viewers to produce or alter images was not enough. He now sought to intervene into traditional television on the level of content as well as form, to facilitate encounters that traditional broadcasting did not provide.

Specifically, Video Commune reflects Paik’s increased attention to the inequality of media flows at the peak of the Vietnam War. Paik’s worldview had been shaped by his early experiences of displacement and migration. Born to an affluent family in Korea in 1932, he had fled to Hong Kong in 1950 at the start of the Korean War; he attended university in Japan before settling in Germany and then the United States. His perspective as a Korean immigrant working in the West gave him a deep-seated sense that the American media failed to address Asian issues responsibly. The root causes of the atrocities of Vietnam, he thought, could be attributed in part to a lack of understanding – a problem aggravated by unbalanced representation on television.32 In ‘Global Groove and the Video Common Market’, Paik wrote, ‘Most Asian faces we encounter on the American TV screen are either miserable refugees, wretched prisoners, or hated dictators’, whereas Asian audiences regularly viewed middle-class white families in American sitcoms; he also asked, ‘Did this vast information gap contribute to the recent tragedies in Vietnam?’33 This political context lent urgency to the content of his broadcast productions. In Video Commune, Paik fought hard to present American viewers with images of Asian men and women that many would not come across elsewhere.

Ultimately, Paik saw the synthesiser experiments and the Japanese pop performances, different as they may appear, as deeply compatible. In the undated memo on global television, he writes in defence of the clips’ inclusion that the ‘spirit of togetherness, of sharing, and participation is and should be the theme of Video Commune’.34 For Paik, the ‘spirit of togetherness’ referred both to interactive art – in which a work is open to viewer interventions beyond the artist’s control – and to art that, while not directly participatory for its audience, deliberately incorporates contributions from other authors. Art historian Claire Bishop’s terms are helpful for distinguishing these modes. On the one hand, Paik aimed with the synthesiser to construct an ‘active subject’ who would be ‘empowered by the … experience of participation’; on the other, with the Japanese clips, he ‘responded to a perceived crisis in community’ by attempting to restore social bonds.35 Here, these two aims clash somewhat: viewers are invited to become agents in the construction of the television picture, but with periodic interruptions – surprise encounters that prevent any feeling of total control.

In a sense, Paik’s desire to foster togetherness through television may be understood as a kind of utopianism, a dream that technology could engender a perfectly harmonious global village. Such is the vision conjured by the broadcast’s title, Video Commune, with its allusion to the collective living communities popular in that period.36 The Japanese compilation that Paik obtained, moreover, had been created in conjunction with Expo ’70, the world’s fair whose slogan was ‘Progress and Harmony for Mankind’. Yet as art historian Dieter Daniels observes of the later Global Groove, Paik’s global community cannot be characterised as simple integration, because it locates ‘the understanding of cultural diversity in the foreground’.37 I would suggest that the deliberately confusing effects of the Japanese segments in Video Commune – many of which include large amounts of untranslated intertitles – similarly complicate any easy notions of smooth, unimpeded global communication.

Video Commune reflects a significant change in Paik’s own approach. Yet it is also symptomatic of a more general shift around 1970, in which many artists began to move away from formal explorations towards more overt social engagement – from minimalism to institutional critique, for example.38 What may be surprising is that Paik remained committed to technology in a period when many artists abandoned it entirely. As scholars have noted, at this moment, discourses in the art world shifted from a general sense that the model of the artist-engineer could revitalise creative practices, to a widespread belief that working with technology amounted to condoning the industry’s complicity with the US military effort in Vietnam.39

Paik was not naïve about technology’s potentially deleterious effects, including its military applications. In the case of electronics, he thought, the essential problem is that technologies themselves are neutral. Television, for instance, aims solely for perfect reproduction of a signal without regard to its content: ‘The whole multimillion-dollar electronics industry has one purpose – re-creation of the source’, he wrote, ‘The nature of the source is not their problem. Electronics has thus been used for military purposes, for censorship, for eavesdropping.’40 For Paik, there were two ways to address this problem: first, to disturb the signal at the moment it reached a receiver, and second, to intervene into the creation of source content itself. He would continue to explore the latter mode in his subsequent work for WGBH, in which he continued to put forward models of community absent from commercial programming. What was never an option for him was to withdraw entirely from the world of technology at a moment when the stakes were particularly high.

Beyond Video Commune

In the early 1970s, WGBH substantially expanded its engagement with artists. After the period of Rockefeller funding, Barzyk spearheaded the establishment of what would come to be called the New Television Workshop, meant to foster artists’ experimentations with television.41 In the intervening years, Paik had made another short for WGBH. Part of a programme inviting artists to accompany performances by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Electronic Opera #2 1972 shows an anonymous hand repeatedly punching a bust of Beethoven and a toy piano bursting into flames. The video was a return to the shock tactics Paik had employed in his early performance art, and a callback to his early desires to disrupt classical music.

Paik’s next major production for WGBH was A Tribute to John Cage 1973, 1976 (hereafter Tribute), a homage to his mentor on the occasion of Cage’s sixtieth birthday.42 The hour-long video incorporates images and techniques familiar from the artist’s previous videos, including the use of the synthesiser, the insertion of Japanese songs and commercials, and even footage recycled from his earlier WGBH programmes. Tribute, however, abandons the loose, heavily abstract format of Video Commune – a style to which Paik would not return – in favour of a quasi-documentary approach. In it, Paik alludes to viewer participation without explicitly inviting it; instead, he presents a picture of shared authorship by incorporating material from a wide range of artists and cultural registers.

The video begins with a reference to participation. As Paik walks down a street with a robot that he and Abe had built, K-456, Connor’s voice explains that both Paik and Cage share a concern ‘that the modern cybernated society might turn people into a parade of mindless robots’. Cage responded to this danger by composing ‘music for audience participation’, while Paik later invented ‘participatory television, in which viewers are no longer robots, but human beings, who can talk back and strike back at their TV sets’. As the video cuts to an excerpt from Video Commune, Connor says, ‘The next segment is created by two passers-by, who dropped into a video commune, and did their own thing’. We then see two familiar figures from that earlier broadcast, who screw up their faces into different expressions as they play with the synthesiser’s warping and colourising effects.

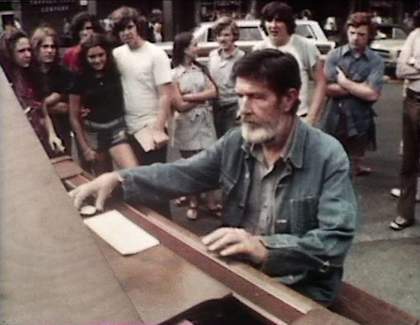

Fig.5

Nam June Paik

Still from A Tribute to John Cage 1973, 1976

Video, colour, sound

29 min

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

© Nam June Paik Estate

Despite this introduction, the video does not include explicitly participatory elements in the mode of the earlier broadcasts. The two centrepieces of the programme are twin performances by Cage, one in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and one in New York City, of 4’33”, a musical piece in which the performer sits in silence while the audience listens to the ambient sounds of their environment. In the first, Cage performs at a piano in the centre of Harvard Square (fig.5). The scene foregrounds New England’s artistic community, much as Video Commune had. Following Cage’s piece, a number of other figures perform on the piano and other instruments, including the composer and artist Maryanne Amacher, who would soon be a fellow at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies; the composer Richard Teitelbaum, then studying at Wesleyan University in Connecticut; and members of the art collective Pulsa, also living in Connecticut. Others, such as the media artist Liz Phillips, then at Bennington College in Vermont, are visible in the audience. The remaining parts of the video comprise conversations about Cage with Wesleyan professor Alvin Lucier, excerpts of Electronic Opera #1, and portions of works by Charlotte Moorman, Stan VanDerBeek and Merce Cunningham. In its collage-like format as well as in its content, the video is less a portrait of Cage than of a community of artists and performers inspired by his ideas.

Newly discovered archival documents reveal how Paik’s plans for Tribute changed over time. Initially, Paik intended a central segment of the video to feature parts of Cage’s most important compositions, which he planned to pair with hit pop songs released in the same years. In part, Paik wrote, the juxtapositions would illuminate the ‘complicated relationships of serious art and pop culture (entertainment industry) in the past 50 years’. He added, ‘THIS IS A SERIOUS PROBLEM. I will restrain from positive or negative judgement. No music art history CAN be written without the integration of two cultures.’43 Paik abandoned this plan, but traces remain: the video includes a long montage of images from the Woodstock festival in 1969, including performers such as Jimi Hendrix; it cuts from the end of Cage’s performance to a catchy Japanese Pepsi jingle; and it ends with an extended routine by a burlesque dancer. Paik understood this openness to all realms of culture as a defining quality of Cage’s work. He told an interviewer, ‘I like John Cage because he took seriousness out of serious art. There is no difference between ritual, classical, high art and low, mass entertainment, and art. I live – whatever I like, I take.’44 It is clear, however, that Paik went much further than Cage in his engagement with popular media and his belief in its ability to generate affective connections among people.45

Paik’s comments on popular culture during the planning of Tribute expand upon interests he had already displayed in Video Commune, with its Beatles soundtrack and Japanese pop hits. Certainly, Paik worried about the mindlessness that the entertainment industry could engender. Yet he also sensed that pop culture, although inextricably related to consumerism and global power imbalances, was a double-edged sword: it might also serve as a shared vocabulary that transcends language. In Tribute and subsequent videos, he combines materials that span the full spectrum of cultural production.

Many of Paik’s videos of the later 1970s and 1980s, made largely with WNET in New York, followed the quasi-documentary format of Tribute. More than a decade later, the artist returned to WGBH for a final project, Living with the Living Theatre 1989. The video explores the Living Theatre, a New York-based alternative theatre company founded by Judith Malina and Julien Beck with the aim of breaking down the divisions between performer and audience. Parts of the video explore the pair’s radical politics: in one segment, they discuss the philosophical and practical problems of dividing labour on communes; in another they visit the grave of the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. Paik’s primary focus, however, is on Malina and Beck’s lives as parents, and their relationships with their adult children. Alongside interviews with its subjects, the video incorporates animations that Paik commissioned from Boston-based artist Betsy Connors, graphics by Paul Garrin, an appearance from Paik’s robot K-456, and musical performances by Janis Joplin that – while bearing little direct relation to the central topic – lend the video a raucous energy in tune with the Living Theatre’s own productions.46

Conclusion

Paik’s WGBH projects demonstrate a shift from inviting participation, in the form of following instructions or turning knobs, to modelling participation, through the incorporation of diverse source material into heterogeneous collages with multiple authors. Although Paik’s turn away from the dialogical dream of ‘two-way television’ may seem regressive, a step back from the technology’s radical but unrealised potential, there were advantages to the artist’s later approach as well. In his early work, Paik had imagined that viewers could modify centralised broadcasts to ‘speak back’ to the machine. Yet these interventions were mostly private, local performances with an audience of one – a single riposte rather than a mutually responsive conversation. Even public uses of the synthesiser were largely self-reflexive, as participants generally employed the machine to modify images of their own faces. From 1970 onwards, Paik pointed his camera’s lens outward to expose viewers to content lacking in commercial programming, from international perspectives to avant-garde art. With his distinctive choppy editing, he left the seams between parts visible and the variety of perspectives tangible. He had learned that he could turn television’s dominant one-to-many model to his own ends.

In the 1980s Paik focused much of his energy on international satellite television. In that context, he returned, for a time, to the dream of a truly democratic, interactive broadcasting system that had continued to elude him. Writing in 1984, however, he also signalled his awareness of a possible danger that such a system might entail: opening additional communication channels to give users increased agency might simply replicate existing power structures. ‘Although’, he wrote, ‘the concepts of freedom and equality may appear to be close brothers, they are in fact antagonistic strangers.’47 That is, creating a truly equitable system might not be a matter of simply increasing access to creative tools; rather, it would take conscious effort and careful attention to ensure that all were given a fair hearing. Paik’s work at WGBH shows him navigating this problem. Initially pulled in the direction of freedom, he later shifted largely to the side of equality.

Yet we should also take seriously the moments, as in Video Commune, in which Paik envisioned these two modes – one directly participatory, and one deliberately crafted to represent multiple perspectives – as two sides of the same coin. Both modes involved a reduction of authorial control – either during the broadcast, when viewers were asked to modify the images emanating from their sets, or before it, when Paik made a work’s initial content permeable to contributions from others. Both strategies aimed to correct omissions in the mainstream media environment: reasserting individual agency in the face of corporate hegemony, or remedying the uneven representation of national, racial and cultural groups. And both certainly had their roots in Paik’s early formation in post-war experimental art circles.48 They were two distinct but related ways to resist what Paik called the ‘fidelity’ of television, its unquestioning reproduction of both electronic signals and social forms.49 At WGBH, assisted by station staff who were strikingly open to taking risks, Paik had the resources and support to explore these modes in depth.

By now, it is commonplace to observe that Paik anticipated the era of video sharing and YouTube, where anyone with an internet connection has access to media channels.50 A more productive approach is to consider the places where Paik complicated the notion that the pure democratisation of media access should be progressive artists’ only, or even primary, goal. It is also easy – given Paik’s quasi-mythical status as the ‘father of video art’ – to forget his specific social perspective: he was an Asian immigrant working in the United States at a moment when the contents of the nightly TV broadcast carried high political stakes. In imagining ways to deliberately elevate underrepresented voices and perspectives within the American televisual landscape, Paik was an early participant in conversations about equitable representation in media that remain critical today.