Over the course of four issues in March and April 1967, the French journal Les Lettres Françaises published a series of articles by the prominent poet-critic Marcelin Pleynet. Collectively titled ‘De la Peinture aux États-Unis’ (On Painting in the United States), and spurred by the author’s recent six-month stay abroad, the essays attempt to analyse the mid-century advancement of North American abstraction embodied in work by the likes of Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko.1 Pleynet contextualises the phenomenon within a broader history of modern art in the US, referring back to the 1886 arrival in New York of the French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, the 1913 Armory show and the migrations of European artists that accompanied both world wars. The central event nonetheless remains the emergence of a new painterly language in many ways distinct from European precedents, and – although this receives less attention in ‘De la Peinture’ – the support of that practical development by the appearance of a substantially new critical model: the formalist criticism of Clement Greenberg. Pleynet characterises Greenberg’s analyses in the latter’s 1960 anthology Art and Culture as ‘among the most precise we have’.2 Pleynet’s own articles, he would later note, were everywhere indebted, in ways he himself had yet to recognise fully, to the ‘didactic efficacy’ of Greenberg’s essays.3

Reading Pleynet’s texts today, it seems surprising that his exposé of post-war painting in the US should have come as news in France at what appears, to North American eyes at least, a notably late date. We might also be struck by his avowed admiration for Greenberg’s writing. By 1967, artists and critics in the US increasingly sought to occupy a space ‘After Abstract Expressionism’, as Greenberg himself had put it in a pivotal essay of 1962.4 The aftermath, in turn, appeared decidedly fragmented. In one area, the colour field painting that Greenberg would continue to champion (and that Pleynet, too, considered the main line of contemporary practice) arose, but, importantly, so did the beginnings of an enduring backlash against Greenberg’s uncompromising alignment of modernism and medium-specificity.5 Neo-dada and pop art had transformed the scene; minimalism, conceptualism and performance were ascendant. In France, however, Greenberg’s writings were all but unknown. Translations of the major texts only began to appear in the early 1970s, largely at Pleynet’s urging, and the abstract painting Greenberg had helped to bring to the fore was still being received slowly and haltingly, primarily under the very different rubrics of ‘action painting’ and ‘art informel’.6 In comparison to the verbose, pseudo-Nietzschean rhetoric of French critics Michel Tapié and Pierre Restany, two dominant voices Pleynet was eager to sweep aside, Greenberg’s plainspoken attentiveness to the literal properties of painting appeared a bracing alternative.7

To be sure, Pleynet himself had already written about abstract expressionist painting in a limited capacity, mostly in the form of exhibition reviews. One might particularly note early essays on Mark Rothko and Franz Kline, both of whom had important – if sparsely remarked upon – exhibitions at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1962 and 1964 respectively.8 Yet ‘De la Peinture aux Etats-Unis’ is far more ambitious in scope, and represents the critic’s first sustained attempt to take a comprehensive view of US painting. And although their author would later bemoan what he came to see as the articles’ many shortcomings, ‘De la Peinture’ was significant insofar as it set up a much more sustained reckoning with the challenges and limits of American painting in and around the journal with which Pleynet was by that point closely associated, the avant-garde review Tel Quel.

Published in Paris between 1960 and 1982, Tel Quel is well known in the United States as a primary vehicle for much of what is now called ‘French theory’. This reputation was secured by the review’s support for and publication of texts by writers including Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, and by Julia Kristeva’s role on the editorial committee from 1970 onwards. Although the journal’s history was in many respects volatile and marked by numerous schisms, Pleynet proved an important constant, serving as editorial secretary from 1962 until its dissolution.9 During this period, the review elaborated what the intellectual historian Patrick Ffrench has characterised as a distinctive theory of literature. He describes how it fundamentally reconfigured the standing of previously under-appreciated writers such as the Marquis de Sade, the Comte de Lautréamont and the dissident surrealists Antonin Artaud and Georges Bataille, even as it substantively informed the production of new literary and poetic work both within and beyond the French-speaking world.10

The journal also developed a unique and broadly influential view of art from the US. Along with its eventual satellite Peinture, Cahiers Théoriques (Painting, Theoretical Notebooks), which appeared from 1971 to 1985, and Catherine Millet’s Artpress, founded in 1972 and likewise distinguished by its critical engagement with art in the US, Tel Quel actively promoted many of the figures flagged in Pleynet’s 1967 articles as the leading lights of post-war abstraction. In so doing, it also fostered the emergence of a generation of artists, famously including the individuals associated with the Supports/Surfaces group, who were similarly committed to thinking through the issues raised by the new developments across the Atlantic. Greenberg believed that painting since the later nineteenth century had evolved through a process of progressive self-criticism, winnowing away references to the external world so as to foreground exclusively formal problems, ultimately underscoring the medium’s constitutive flatness. Both singly and collectively, the writers and producers of the new generation defined their vision explicitly in relation to – and increasingly against – what Pleynet came to portray as the limitations of Greenberg’s formulations on ‘the modernist reduction’.

Taking ‘De la Peinture’ as a point of departure and recurrent touchstone, and engaging additional writings by Pleynet from the 1960s and 1970s, this article has a double aim. It will first draw out the broad contours of Pleynet’s conception of American painting,11 before turning to the work of the US expatriate James Bishop, repeatedly held up by Pleynet as an exemplary practitioner. Addressing key canvases and critical documents, I suggest that Bishop and his admirers took particular issue with Greenberg’s ‘technocratic’ reduction of the painter, and sought to articulate an alternative, more nuanced model of painterly subjectivity. This body of work constitutes a crucial episode in the transnational reception of American art and criticism in the decades following the Second World War.

The subject of painting

For Pleynet and his colleagues, the question of ‘the subject’ stood at the very crux of modern culture. Tel Quel was fully engaged with broader debates about the role and function of the subject in the human sciences that reconfigured French intellectual life in the 1960s and 1970s, and with developments in psychoanalysis that drew on the writings of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, among others.12 The journal presented itself as thinking through what Pleynet identifies as ‘the least easily rationalisable manifestations of the human animal’s symbolic activity’.13 While the group’s engagement with unconscious desire is in certain respects inherited from surrealism, Pleynet and other core contributors came to focus increasingly on the constitutive role of religion in the Western tradition. Part and parcel of this project was a sustained critique of what Pleynet dubbed ‘the secular illusion’: the failure of an apparently non-religious modernity to grapple with aspects of the cultural past it often seemed to him merely to set aside.14

For Pleynet, art appears to have been a way of working through what he saw as the crisis of the subject, inaugurated by the withering of religion and the effective collapse of Christianity in particular. The modern separation of church and state was deeply rooted in French philosophical and political thought from the eighteenth century forward, becoming formalised in French law in 1905. Much of Pleynet’s writing during the 1970s casts this separation in terms of a loss of ‘mediation’ between individuals and state institutions, and struggles to think through the consequences of that uncoupling in both economic and, more primordially, libidinal terms. In ‘De Pictura’, a 1975 essay written to accompany an exhibition of work by the painters Bishop, Robert Ryman, Agnes Martin and Wolfgang Nestler at the Galerie Rencontres in Paris, Pleynet argues:

It is a question of what, in the process that constitutes the relation between the subject and the State, takes over the mediating role of religion; and if there is still mediation, then what is the subject of this new mediation? This is a crazy, insane question, when one considers the type of contract with the unconscious that the religious structure implied for centuries on end.15

What, in other words, becomes of the libidinal drives and investments that religion once served to repress and sublimate? For Pleynet, all of modern culture circles endlessly around the perennially unsatisfied and largely unrecognised need to reconceive both individuality and collectivity after Christianity. To cast the problem at this level is to see modern culture as engaged with issues beyond the scope of any one national tradition. Rather, modernism becomes the name of this extra-national attempt to acknowledge and address ‘the community of separated subjects’ that results from the loss of the religious contract.16

North American painting of the 1940s and early 1950s, Pleynet believes, takes over all of this. As evidence, he cites Jackson Pollock’s often quoted assertion that the problems of modern art have no nationality, as well as the search by ‘the painters of the 1940s and Barnett Newman in particular’ for a ‘new subject’.17 Yet that wide-ranging attempt to reconceive subjectivity was undermined and ultimately baffled by another intellectual inheritance: what the critic presents as the faith in progress, including the possibility of ‘evolutionary’ progress in art, produced by the positivist currents of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.18 Present in modern culture from the first, Pleynet allows, this tendency finds a uniquely hospitable climate in the US in the years following the Second World War. Producers there had been largely sheltered from the fascist crises that convulsed Europe in the 1930s, and therefore from the profound disillusion inflicted upon the continent’s artists and intellectuals. Indeed, Pleynet thinks, the flight of European modernists only served to reinforce US exceptionalism: ‘Displaced geographically and historically, the henceforth extra-national culture that came to view in New York was experienced and considered as a national privilege and progressively cut off from its original determinations’.19 It was, one might say, provincialised.

This detachment of modern culture from the question of the subject is manifest in what ‘De la Peinture’ already identified as the extreme focus, on the part of younger artists, on ‘formal problems’: questions of structure and spatial organisation.20 This rationalistic approach appears to Pleynet to consciously or unconsciously sidestep a host of less readily stabilised aspects of the painterly enterprise, foremost among them the matter of colour. ‘Where colour is treated’, Pleynet notes, ‘it is done so in an optical fashion’ – that is, as disembodied hue.21 His immediately preceding remarks make it clear that he is thinking especially about the work of Frank Stella, whose approach he provocatively qualifies as ‘border[ing] dangerously on technocratic ideology’.22 It is worth noting that Stella’s output was at this point closely identified with the notion of ‘deductive structure’, consisting substantially of pictorial compositions clearly derived from, if not wholly dependent upon, the framing edges of his differently shaped canvases.23 But the critic also expresses reservations about the work of Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, noting with respect to the latter artist in particular that he yearns to see him ‘engage himself more dangerously (by taking more risks) with the problem of colour’.24

These lines establish colour as a central practical and theoretical crux. Subsequent essays develop this point, presenting colour as intimately entangled in a host of social and subjective determinations, including the libidinal economy Pleynet believes had previously been regulated by religion. The failure of formalist discourse to grapple more intensively with the problem of colour therefore becomes a striking index of a broader impoverishment. This emerges clearly in a key text of 1975, in which Pleynet presents the North American high modernist discourse of the 1960s as usurping the comparatively impure questioning of the first generation of abstract expressionists:

The passage from Abstract Expressionism to the formal ritual of an art that strives toward the stripping-away of all extra-visual meanings, and the contradictions that it puts in play, are from this point of view highly instructive. Since it comes down to reducing to a national lineage what is an essentially extra-national progressive movement, the efflorescence of the American pictorial phenomenon of the years ’40-’45 will be registered as such without the causes that produced it ever being interrogated. Thus, beyond the movement that carries and constitutes the force of the artists of the ’40s, there will develop a flattened reading of their works reduced – in terms of plane, line, and surface – to the two-dimensionality of optical objects.25

Borrowing language from the Paris leg of E.C. Goossen’s controversial travelling 1968 exhibition The Art of the Real: USA 1948–1968 – a show that had presented US minimalism as essentially continuous with abstract expressionist and colour field painting – Pleynet continues:

If one follows the analyses that are put forward, the youngest [painters] find nothing to borrow from the work of their elders apart from a few features and technical processes, dismissing the ‘remainder’ along with everything capable of evoking an ‘extra-pictoriality’ of painting. Paradoxically, the search for a ‘new subject’, for a ‘new sublime’, for a ‘heroic’ expressionism, on the part of the painters of the ’40s and Barnett Newman in particular, thereby gives way to an ‘object-like’ art, systematically repressing all subjectivity. But it goes without saying that from subjective obliteration to subjective obliteration, from ‘modernist reduction’ to modernist reduction, from flattening to flattening, the tableau tends to lose all specificity and become indistinguishable from the real object (or undifferentiated surface).26

Here I want to underscore the ways in which subjectivity itself appears to fall, in Pleynet’s reading, on the side of the uneasy ‘remainder’ increasingly banished from formalist thought. The works resulting from this process, he believes, give themselves over to a kind of sterile and increasingly decorative repetition before ‘progressively sinking into a morose and nostalgic rehashing of ideas, the symptom of a crisis whose solution cannot be exclusively American, whether historically or geographically speaking’.27 Modernist art from the US, read in these terms, is at once the genuine taking-over and transformation of the deepest contradictions in modern culture, and the site (or non-site) of a missed encounter – a failure to think through that culture’s generative conditions.

James Bishop’s exemplarity

Pleynet’s problem, briefly put, is to conceive painterly subjectivity differently, taking into account the constitutive force of precisely those aspects of the medium brought to the fore by Greenberg’s formalism – flatness, boundedness, the specific properties of different supports and pigment types – while also acknowledging the less ‘easily rationalised’ aspects of the human subject then of interest to Tel Quel. In this endeavour, one artist in particular seemed to show him a way forward: the US painter James Bishop.

A succession of texts of the 1960s and 1970s clearly establish Bishop’s emblematic status for the Tel Quel group. In ‘De la Peinture’, Pleynet had included him alongside Louis, Noland and Stella as one of the leading younger painters from the US, although with no further explanatory gloss.28 He had previously devoted a 1964 article to Bishop, published in English in the Lausanne-based Art and Literature under the heading ‘James Bishop: An Experimental Reality’.29 In 1965 Tel Quel published another important text on Bishop by Sollers, suggestively entitled ‘La Peinture et son Sujet’ (Painting and its Subject).30 Both authors continued to write about Bishop into the 1970s, and the artist’s work featured prominently in Peinture, Cahiers Théoriques. An untitled drawing of 1969 was featured on the cover of issue 8/9, in February 1974, which contained the first French translation of Greenberg’s ‘Modernist Painting’ (1960); the artist also garnered reviews and repeated mentions by editor Louis Cane, among other prominent painter-theorists in the Tel Quel orbit.31 One might also note Bishop’s contemporaneous presence in Artpress, which devoted a cover story to the artist in 1974.32 In this context, Bishop appeared as an exemplary figure, one who had learned to make compelling use of the most radical achievements of post-war American painting precisely by getting ‘outside’ that tradition and its prevailing discursive frameworks.

Fig.1

James Bishop

Water 1961

Private collection

© James Bishop

Fig.2

James Bishop

News from Ferrara 1963

Private collection

© James Bishop

The painter’s distance is construed as at once geographic and historical. Born in Neosho, Missouri, in 1927, Bishop studied painting at Washington University and Black Mountain College, where he worked with Esteban Vicente and explored an openly gestural style. He also took courses in art history at Columbia, where he especially followed the teaching of Rudolf Wittkower and Meyer Schapiro. He travelled to Europe in 1957 and settled in France the following year. At the time, he ‘still had something of the “true believer” feeling’ with respect to abstract expressionism, and early Parisian paintings such as Water 1961 (fig.1) reveal particular affinities with the work of Robert Motherwell, Newman and Rothko, among others.33 Although Bishop has never renounced this association, he soon rethought it substantially. He closely followed subsequent developments in the work of Louis, Noland and Stella (all of whom showed in Paris in the early 1960s) and – more importantly, in the eyes of his French critics – he engaged with the tradition of European art. Italian painting of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was a particular interest for Bishop, with works such as News from Ferrara 1963 (fig.2) evoking the achievements of Cosmè Turra, Francesco del Cossa and other Ferrarese artists.

For Pleynet, this deeper historical perspective did not simply allow Bishop to see more; it allowed him to see otherwise. It effectively attuned him to exactly that aspect of pictorial tradition which the critic believed had been rendered unthinkable by the ‘modernist reduction’: ‘the material ground of colours, whose captivating power he now draws forth precisely where it has been repressed, at the very site of the greatest resistance’.34 By embracing colour in all its fascination – in its appeal to all that remains least easily ‘rationalisable’ in the human subject – Bishop avoids ‘“avant-gardist” illusions and their technicist trap: the flattening of colour, optical illusion’.35

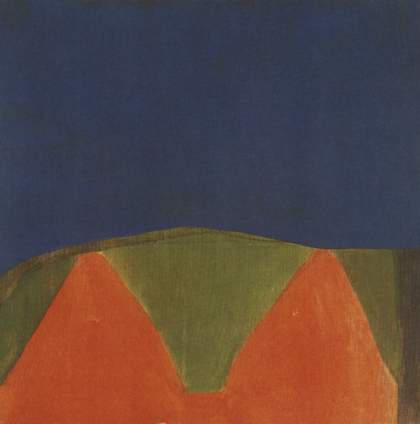

Fig.3

James Bishop

Proof 1967

Private collection

© James Bishop

These lines introduce Pleynet’s most developed statement on Bishop, the 1971 ‘La Couleur au Carré, les Rides, le Dessein’ (roughly translated as ‘Colour Squared, Wrinkles, Drawing’). When he wrote them, the critic would have had in mind the stratified, just-off-monochrome canvases the artist began making after 1966, following his return to the US and his initial first-hand encounters with US minimalism. Produced through a process that saw Bishop laying his stretched canvas on the floor and then tilting and rocking the support so as to disperse deposits of very liquid oil paint about the surface, paintings such as Proof 1967 (fig.3), marry all-over or rectangular fields of layered, subtly variegated colour to regular configurations of repeating and abutting bars and squares. The repeating forms, as Pleynet’s title aims to capture, are demarcated by wrinkle-like ‘lines’ generated entirely by the controlled overlapping of pigment from adjacent areas, a technique the critic understands as subverting the traditional secondarity of colour relative to drawing.36 Exhibited in New York and throughout Europe from the late 1960s, these canvases remain fundamental in the artist’s production.37 In the following, however, I want to focus on an earlier painting that in many ways made the later works possible.

Fig.4

James Bishop

Hours 1963

Private collection

© James Bishop

Bishop has frequently cited Hours 1963 (fig.4) as a key turning point in his work. The pooling and running of liquid oil paint appears in its central portion, making it the first painting where he employed the method that he would use consistently in his abstractions after 1966. The canvas figured prominently in Bishop’s 1963 exhibition at the Galerie Lawrence, then one of the best-known galleries in Paris to focus primarily on work by American artists, and appeared on the exhibition’s invitation card. It also became an important touchstone in Pleynet’s writing. Hours is reproduced in the critic’s 1964 article ‘James Bishop: An Experimental Reality’ and is discussed at length in ‘La Couleur au Carré’, a text originally written to preface a landmark presentation at the Galerie Jean Fournier, which was another space in the capital renowned for its openness to new tendencies in the US.38 Read within the context we have established thus far, Pleynet’s essay is in many ways a sustained response to the idea of the ‘modernist reduction’ in the form of one privileged case study. At stake in the essay’s key idea, the curious notion of ‘colour squared’, are ideas of multiplication and proliferation that Pleynet takes to fundamentally unsettle the seeming containment of Bishop’s literally square formats.

Fig.5

James Bishop

Untitled 1962

Private collection

© James Bishop

Fig.6

James Bishop

Untitled 1962–3

Private collection

© James Bishop

Already in 1964, the critic had underlined the constitutive importance of these formats, suggesting that ‘one of the first problems for this painter is the square or rectangle on which he will paint’.39 Sollers’s 1965 text also notes that ‘James Bishop’s paintings are made with a view to the surface unit, that is to say the square’.40 Hours inherits its square support from the artist’s immediately preceding canvases, including two untitled examples from the years 1962–3 (figs.5 and 6). As in those earlier instances, Bishop appears highly conscious of the framing edges, articulating the wide internal frame of deep azure and the less sharply defined but roughly quadrilateral zone painted primarily in thinned-out washes of what appears to be the same blue pigment. Reiterating the physical shape of the format within the pictorial scaffolding, these structures register as at least loosely deductive, thereby tying Hours to one of the most prevalent tropes in formalist art and criticism. Bishop, like his peers in the US, begins by acknowledging the canvas as a separate unity – indeed, by radically accentuating its objective reality. Described by the artist himself as ‘the most neutral form’, the square appears cleanly detached from subjectivity.41

Yet Hours’s seemingly impersonal geometry serves primarily as a foil for a host of ‘subjective’ decisions. There are, to begin with, the imperfections of Bishop’s formal reiterations. The bold, brushed-in frame is not perfectly rectilinear but subtly irregular: the edges waver, and the upper internal border slants downward toward the right. There are additional idiosyncrasies in the diluted interior ‘square’, where Bishop is no longer drawing the contours in any conventional sense. Disrupted from within by a vertical length of white canvas and completed in the upper left quadrant by a wedge-shaped area of olive green paint, the entire configuration is at once off-kilter within the frame and asymmetrically sectioned within itself. Bishop’s divisions, one might say, openly produce remainders – a kind of excess within what appears initially as an emphatically self-enclosed structure.

Bishop’s use of colour further supports and indeed intensifies this impression. In an important departure from the painter’s earlier works, in which multiple layers and veils of more or less saturated pigment had largely obscured the cloth support, Hours reveals significant areas of exposed, primed canvas. This feature points in part to the painter’s encounters with works by Louis and Noland, who also exhibited at the Galerie Lawrence in these years.42 In Hours, as in the canonical contributions of those signal predecessors, the found colour of Bishop’s commercially prepared support ceases to function as a neutral ground and appears, instead, as a highly active element in its own right. In the view of the Tel Quel writers, Bishop confronts the whiteness of the non-painted cloth as the chromatic equivalent of the square. Seen as the sum of all colours, white appears another kind of unity. And here, too, the painter divides and displaces this apparently ‘unified’ identity. Pleynet writes: ‘Reversing the proposition that the canvas is prepared so as to receive form and colour, Bishop surmises that the form (the closure of his square canvas) comes to him already coloured and that it is white – that is to say, that the infinite “germination” of colours is already at work.’43

The intervention again proceeds in several steps. Looked at anew, the striking internal frame does not simply echo the work’s outer limits but also rivals the support’s inherent, optically dazzling whiteness. Precisely in so doing, however, it reduces that whiteness to one colour among others.44 Its unity, in other words, can no longer be imagined as standing above or beyond the finite hues. Yet the watercolour-like areas in the central zone do something else. As less definitive forms in uneven saturation and, in the case of the green wedge, a decidedly impure tone, these painted areas appear to Pleynet as if welling up from within the whiteness, effectively signalling the heterogeneity at its heart. In a formula deliberately reminiscent of the writing of Jacques Derrida, Pleynet calls this the ‘always already there-ness of colour’ (ce toujours déjà-là de la couleur).45 In this sense as well, the painter’s divisions produce an apparent surplus, the colour ‘squaring’ or multiplying itself indefinitely. In so doing, they suggest a way that colour might count in terms other than optical flattening, becoming associated instead with something like an irreducible reserve or supplement of subjectivity.

Conclusion

More than fifty years after the publication of ‘De la Peinture aux États-Unis’, Pleynet’s view of modernism remains largely unfamiliar outside of France. Many of the texts cited here have yet to be translated into English, along with the preponderance of the material gathered in his important 1977 anthology, Art et Littérature (Art and Literature). Especially telling, perhaps, is the fact that the one major English-language edition of Pleynet’s writings to appear thus far – System and Painting (1984) – comprises the critic’s historical essays on Matisse, Piet Mondrian, the Bauhaus and the Russian avant-garde, but not his texts on contemporary painting in France.46 Recent scholarship and several remarkable exhibitions have helped to create a new openness to Pleynet’s insights and objects; I think in particular of the seminal As Painting: Division and Displacement, held at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, in 2001, which called attention to a range of post-war French practices and the intellectual milieu in which they developed.47 Yet Tel Quel’s sustained engagement with post-war American art and criticism still awaits broader recognition within US art history.

It is perhaps unsurprising that this reception is still emerging. Although critiques of Greenberg were ubiquitous in the 1970s, Pleynet’s continued attachment to painting – and indeed, to the very notion of modernism – rendered his writing largely illegible in a situation fundamentally transformed by American minimalism and the adventures of objecthood. The Tel Quel writers and the painters they championed seemed simply to have missed the lessons of the 1960s. ‘French theory’, meanwhile, was received essentially as a set of frameworks for negotiating the end of painting and the passage beyond medium – frameworks, that is, for putting paid to Greenberg once and for all.48 That these narratives largely continued to pass, as Pleynet once put it, ‘from subjective obliteration to subjective obliteration’ might now give us pause.49 Perhaps the time has come to fundamentally rethink the subject of American painting, in the essential doubleness of that phrase.