We knew [Greenberg] was a kingmaker; we knew he had immense power.

Gene Davis1

In September 1962 the Washington, D.C. painter Gene Davis – rather unknown at the time, but growing in critical acclaim – arrived in New York. He took an apartment at the Chelsea Hotel, the legendary haunt of the day’s reputed (and infamous) artists, musicians and writers. The choice of venue set him in the footsteps of his more famous abstract expressionist contemporaries such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Davis invited the renowned American art critic Clement Greenberg to visit his new studio, and upon learning of the visit, the Chelsea Hotel’s building manager arranged for Davis’s walls to be freshly painted white so as to impress the critic.2

A short while after the visit, on 5 October 1962, Davis wrote a letter to Greenberg about their encounter and addressed the less-than-favourable impression that his recent coloured, stripe-based works had left upon the critic:

Your observation that I tend to paint flat-footed in my recent work hit the bullseye. Since I returned home, I have changed a few of my existing works by painting atonal stripes on the far edges or changing the color of a stripe here and there … You have the sharpest eye I have ever encountered. It almost seems that you know more about what I am trying to say than I do.3

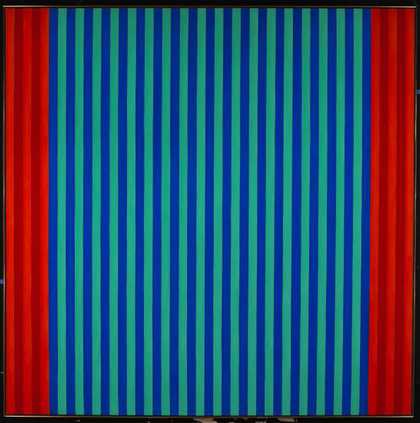

Gene Davis

Untitled 1962

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

© Gene Davis

Following Greenberg’s advice, it would appear that Davis turned a corner: ‘This week, I started work on a new painting inspired by your remark on flat-footedness. Damn if it doesn’t have an entirely new look.’4 The work was Untitled 1962 (fig.1).

At the outset of his October letter to Greenberg, Davis also mentioned a conversation with Elinor Poindexter, a Manhattan dealer representing some of the era’s leading abstract expressionists, including Richard Diebenkorn, de Kooning and Franz Kline. In September 1963, another letter to Greenberg recorded that Davis’s efforts had been rewarded at long last with a debut at Poindexter Gallery. ‘The opening is 5 to 7, and, needless to say, I would be most honored if you could come,’ Davis wrote, then adding, in a moment of self-deprecation, ‘But I’m sure you have more pressing things to attend to, and, if you can’t make it, I will understand’. Regaining his composure, the artist concluded solicitously, ‘Clem, I’ve never forgotten your admonition against painting flat-footed and in my upcoming show I hope you will see some of the fruits of it.’5 Although representation at Poindexter would have been hugely validating, Davis naturally also wanted Greenberg’s attention and approval. Yet Davis was new to the scene, and Greenberg was at the time one of the most influential critics working in America.

Looking back on this earlier part of his career in 1978, Davis appraised the situation quite differently, writing in Art in America that his relationship with Greenberg was ‘from a discreet distance’.6 Later in the same article, Davis remembered that ‘I often stubbornly resisted his suggestions and observations about my work’, although ‘I came to see in retrospect that he has a truly first-rate eye’.7 As the art historian Joan Kee has shown, by the end of the 1960s, an endorsement by Greenberg amounted to being ‘acceptably Establishment’ and therefore the very opposite of that to which a young, emerging artist might aspire.8 Indeed, the early 1960s was drastically different from the latter part of the decade, both artistically and critically. Greenberg’s claim that the best modern art rose above mere politics fell flat in the later 1960s, an era preoccupied with anti-governmental and anti-capitalistic countercultures worldwide. To continue to follow Greenberg – the ‘kingmaker’ of the epigraph above – amounted to a passé alignment with predominant political and commercial elitism.

The subject of this essay is a seeming paradox: how did a critic who argued for the radical detachment of art and politics in the face of totalitarianism in the 1940s and 1950s then opt into mainstream politics in the 1960s? Looking closely at the intense connections between the artistic cultures of Washington and New York in the late 1950s and early 1960s puts the issue into clearer focus. Although Washington might have seemed ‘provincial’ in matters of culture in comparison to New York, both were (and are) powerful places. While New York is the United States’s centre of finance and contemporary art, Washington is its national capital and administrative centre. It is precisely because of its powerful political role that Washington has been home to an educated class of professionals. Due to its wealth and privilege, this class was privy to knowledge of culture and had an interest in cultivating an exclusive taste in the arts. This essay will therefore present two Washingtons: one national and the other local. The ‘national’ Washington represented political power on an international stage, while the ‘local’ Washington was, as far as avant-garde tastemakers in New York were concerned, a cultural province that saw its first stirrings of contemporary cosmopolitanism during the early 1960s.

It was at this time that, owing to the influence of a young and glamorous President John F. Kennedy and his fashionable First Lady Jacqueline, Washington began to experience something of a cultural renaissance. In hindsight, we can see that Washington’s local style – its eponymous Color School – became embroiled in, and even central to, the art critical polemics usually associated with New York artists. In particular, the work of the Washingtonians Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis came to reinforce Greenberg’s formalist modernist position within an especially precarious art world – one that was already restlessly moving beyond Greenberg’s supremacy, as pop and minimalism took centre stage.9 Looking at the US as a whole, the West Coast scene, specifically in Los Angeles and San Francisco, was more raw but up-and-coming, and prided itself on liberation from East Coast fussiness.10 Due to geographical proximity, however, Washington still remained very much within New York’s orbit, despite its own momentary sparkle. As the Washington-based artist Anne Truitt lamented in 1966, artists in New York ‘could figure out a way of living in which art could be their lives’ – an option not yet available in the same way to Washingtonians.11

This paper will first set the scene by describing the influence of Louis and Noland, and, more briefly, their colleague Anne Truitt, on Greenberg’s criticism in this period. Greenberg’s experiences with these Washington artists coincided with certain shifts in emphasis in his essays, especially pertaining to his essential beliefs about painting. I will then discuss Washington’s political influence on Greenberg through a brief analysis of his work as a United States cultural attaché in the late 1950s and 1960s. Finally, this paper will return to what Gene Davis perceived to be the allusions in his own work, including an admiration of jazz: a trait shared by many abstract painters, including Greenberg’s own hero, Piet Mondrian. It is my belief that Davis’s ‘flat-footedness’ in Greenberg’s eyes was due to the reference to such a popular genre, and indeed, to the artist’s further openness to various forms of popular culture. Seeing what constituted ‘failure’ to Greenberg allows us to examine the opportunities presented by an oppositional relationship with the critic’s prescriptive analyses.

The Washington Color School

Fig.2

Sam Gilliam

Simmering 1970

Tate T01326

© Sam Gilliam

Like so many so-called ‘movements’, the Washington Color School was not organised as a school, but it was, indeed, a ‘thing’, to borrow a phrase from the minimalist Truitt, who worked in Washington for the majority of her long career. In 1963 Truitt wrote to Greenberg, a longtime friend, to share news about their mutual friend, the artist Mary Meyer: ‘I thought you would be interested to know that Mary … showed … new paintings at her opening, which fit into this touted Washington School thing very well. She uses a circular stretcher and paints in a way imitative of Ken’s, soaked in flat areas of spiral color.’12 ‘Ken’ – Kenneth Noland – was key among the Washington community of artists; he was a storied teacher and a supportive presence for artists in the city before he moved to New York in 1962. Truitt and Meyer were very close friends, but as Truitt’s letter makes clear, she distinguished herself from Meyer artistically; to Truitt, Meyer’s style appears to be the one more obviously influenced by Noland. For those who accepted the label (or at least did not object to it), an affiliation with the Washington Color School was – if not a school as such – a way of holding a position in the artworld and maintaining the stylistic relevance of a large and diverse group that included Gene Davis, Howard Mehring, Thomas Downing and Paul Reed.13 Significantly, at a time in which the critical rhetoric of the practice of painting was highly masculinised, the Color School included women – Meyer and Hilda Thorpe. It also included African American artists such as Sam Gilliam, highly regarded for his monumental painted and draped canvases (see Simmering 1970; fig.2), and the retired schoolteacher Alma Thomas. This is an important point given Washington’s history as a centre of vibrant black culture and the nexus of the American North and South.

Noland and Louis were major influences on the Washington Color School, but never claimed an affiliation. Noland was from Asheville, North Carolina, a town in the Appalachian Mountains, and was a student of the geometric abstractionist Ilya Bolotowsky at Black Mountain College, a celebrated liberal arts institution that attracted America’s leading artists as members of its faculty. It was around this time – 1950 or 1951 – that Noland befriended Greenberg at Black Mountain, where the critic was in residence for a summer with Frankenthaler.14 Louis was twelve years Noland’s senior. He was from Baltimore – less than an hour’s drive from Washington – but had lived in New York City during the Great Depression, working for the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. Louis relocated to Washington in 1952 and began teaching at the Washington Workshop Center for the Arts, which is where he met Noland, who was also employed there as a teacher. A mutual interest in the paintings of Pollock brought them together. Louis in particular had an affection for Pollock’s recent work, an influence that can be seen in Louis’s painting from 1950 to 1953. He was particularly attracted to the wall-sized format, dripped and poured enamels and resins on unprimed canvas, and a palette emphasising black with white accents. This latter quality was quite the opposite to Louis’s colourful later style, for which he is best known.15

Fig.3

Jackson Pollock

Yellow Islands 1952

Tate T00426

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.4

Helen Frankenthaler

Mountains and Sea 1952

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

© Helen Frankenthaler/All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

In April 1953 Noland and Louis made a trip to New York City. Noland promised to introduce Louis to Greenberg at the Cedar Street Tavern, the infamous haunt for artists located in Greenwich Village, with the hope of persuading the critic to facilitate an introduction to Pollock. Although this introduction failed to take place, Greenberg organised for them all to visit Frankenthaler’s studio. She was only twenty-three years old, but already the subject of acclaim in the New York scene. At her studio, the artists conversed about the practice of staining, a tendency in Pollock’s work in 1951–2 in which the artist thinned industrial enamel to the point that it could be poured by hand onto unprimed canvas or squirted onto the surface with a syringe (a technique evident in Jackson Pollock, Yellow Islands 1952; fig.3). Frankenthaler explained how she adapted this technique in her own work, and Noland and Louis observed this firsthand in the studio in her painting Mountains and Sea 1952 (fig.4), which combines expanses of thinned colour that both fill in and exceed the boundaries of drawn shapes.16 In a 1971 interview, Noland remembered from this meeting that ‘Frankenthaler showed us a way to think about, and use, color’.17 Louis said that Frankenthaler was ‘the bridge between Pollock and what was possible’.18

The unifying formal principle of the Washington Color School is an experimental approach to a dazzling array of colours, which is also borrowed from Noland and Louis. In the same New York weekend, Louis introduced Noland to Leonard Bocour, the manufacturer of Magna, a glossy acrylic paint that was one of the first synthetics commercially produced for artists. Louis had already been using Magna since 1948, although he was mostly interested in the darker shades and black. Even so, the invention of Magna had three advantages. First, if the pigment was mixed with enough mineral spirit to pour, it could bleed into the weave of the canvas with very little to no surface incident, and dry very quickly. Second, when a painter dilutes oil-based paint, colour saturation is often lost – an effect that we see in Frankenthaler’s muted compositions – but this was not so with Magna, which allowed the artist to fill expanses of the canvas with brilliant, high-keyed hues. Third, since synthetic pigments like Magna are suspended in water-clear polyester resin, they do not yellow as much over time, and thus retain their maximum optical force. Seeing Frankenthaler’s soak-stain method and her freer approach to colour no doubt allowed both Noland and Louis to think more expansively about the chromatic potential of Magna, tubes of which they brought back to their studios in Washington.19

Along with Noland and Louis, Anne Truitt completed the core group, although the peripatetic lifestyle she led as a result of her husband James’s career as a journalist resulted in several entrances and exits from the Washington scene. Notwithstanding this, the pair was well connected. Truitt first met Noland at the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) in Washington in 1948, where he was a teacher, but their friendship flowered when she enrolled in his life drawing class in the spring of 1953, which coincided with the time of Noland’s trip to New York with Louis.20 There had been a small group of intellectuals guiding the programme at the ICA in the 1950s, hosting modernist luminaries such as Marcel Duchamp, Naum Gabo and Rufino Tamayo. Anne and James Truitt left Washington in 1957 for San Francisco, and while in California they met and befriended Clement Greenberg. When they eventually returned home in 1960, they came back to a Washington art world ennobled by the presence of President-Elect Kennedy and his wife. Unlike other Presidents before him, Kennedy singled out the local, contemporary Washington ‘writers, artists … and heads of cultural institutions’ to engage in a productive relationship with his administration.21

Fig.5

Morris Louis

Point of Tranquility 1959–60

Hirshhorn Museum of Art, Washington, D.C.

© Estate of Morris Louis

Fig.6

Kenneth Noland

Gift 1961–2

Tate T00898

© The estate of Kenneth Noland/VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2019

By this time Noland and Louis had established their signature styles. Louis’s billowing flumes of jewel-toned colour, layered one over the next, extended to the edges and near-edges of the unprimed canvas – as seen, for instance, in Point of Tranquility 1959–60 (fig.5). Noland’s ‘bull’s-eye’ paintings, such as Gift 1961–2 (fig.6), radiated energetically from a central disc. Both artists’ work was aggressively championed by Greenberg, who endorsed colour field painting as the proper inheritance of modernism in his 1962 essay, ‘After Abstract Expressionism’. Greenberg was especially enthusiastic about Barnett Newman’s intense, open canvases, and his approval hinged on the quality of the artist’s ‘color-space’: ‘[C]olor is given more autonomy by being relieved of its localizing and denotative function … it speaks for itself by dissolving all definiteness of shape and distance.’22 Yet the work of Noland and Louis suggested more than mere colourfulness – they suggested a new, sensuous experience of colour released from the constraints of picturing or of an imposed narrative.

Through the combined efforts of Noland and Louis (and their appeal to Greenberg) the conceptual distance between the art scene in Washington and New York dramatically shortened. In 1961, Greenberg recommended Noland and Louis to André Emmerich – a Manhattan dealer, friend of the painter Robert Motherwell and an ardent supporter of new modernist painting and sculpture – who enthusiastically took them on. Emmerich had opened a new gallery two years earlier in 1959 in the Fulton Building on 57th Street in Midtown; such a location strategically presented artwork to buyers in an elegant, modern, centrally located space. Back in Washington, the charismatic Noland attracted a group of artists eager to learn from his example: Davis, Mehring, Downing and Reed. To quote Truitt’s words in an unsent letter to Greenberg, the newfound attention paid to artists in Washington ‘was practically exhilarating and blew away the miasmic vapors of provincialism, which have never really come back’.23

Fig.7

Anne Truitt

Insurrection 1962

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

© Anne Truitt

Truitt quickly found a place in the inner sanctum of this intimate group. She rented a space in Noland’s studio, experimenting intensively with nuances of colour as applied to geometric sculpture, resulting in the creation of works such as Insurrection 1962 (fig.7). In the summer of 1962, a sequence of events surrounding Louis’s untimely death led unexpectedly to Truitt’s advantage. The Truitts hosted a private reception before Louis’s funeral at their home in Washington on 9 September, with guests including Greenberg, Emmerich and the critic and curator William Rubin. At Rubin’s urging, Emmerich visited Truitt’s studio the same day and, sensing the importance of the work he saw there, offered her a solo debut, which took place in February 1963. The show at Emmerich was akin to the fulfilment of Greenberg’s prophecy; when he had originally seen Truitt’s sculptures, he proclaimed ‘Now there will be three in Washington’ – Noland, Louis and Truitt.24

It is striking that just as what Truitt had called the ‘miasmic vapors of provincialism’ were departing from Washington, the New York establishment nonetheless imparted a hierarchy there, one that was fashioned in its own image. Greenberg’s crowning of the ‘three in Washington’ set Noland, Louis and Truitt apart from their ‘followers’ – the ‘Washington School thing’, in Truitt’s words. The particular inclusions and exclusions were perhaps unintentional, but we get a fairly clear idea of how it was perceived by artists in Washington via Truitt herself in that same unsent letter to Greenberg from 1965:

All those painters [Noland] left behind [crossed out in the margin: ‘and how cruelly and meanly’] – are still put-putting along in the direction toward which they were wrenched, lured, persuaded – and in which they were finally confined by Morris’s and Ken’s success. Morris’s work was, it seems to me … even more important than Ken’s in the ’50s: he was watched and emulated by his students and by Ken’s because Ken told them to.25

In other words, students were seduced by Noland’s and Louis’s styles, believing them to be leading the modernist charge, but the students were inevitably overshadowed by their teachers.

Greenberg and a changing political context

Despite these observations, I wish to leave the impression that this period was useful for Washington’s artists and arts institutions. Kennedy officially entered office in 1961. He and his wife Jacqueline were young, glamorous, progressive and cosmopolitan, and the administration and staff newly populating Washington in the early 1960s carried themselves with the same buoyancy. Modern art finally had a home in Washington and the Color School was its ideal vehicle: exorcised of the stronger emotions underpinning abstract expressionism, these painters’ works were cool, yet ebullient; subtle, yet grand – qualities that were understood also to describe the Kennedys.26 Galleries popped up and flourished in fashionable neighbourhoods – Georgetown, K Street, Dupont Circle – and work sold.

As Greenberg wielded his influence among Washington artists, the federal government in Washington was playing an increasing role in promoting him as the official voice for American culture abroad. Abstract expressionism, once reviled by the American public, had subsequently been ingested into mainstream culture as an example of free expression and spontaneity, shored up by the enjoyments of a democratic life in the West in stark contrast to repression behind the Iron Curtain. Many art historians have written about this in detail – Serge Guilbaut, Eva Cockcroft, Paul Wood, Jonathan Harris, Charles Harrison and Francis Frascina are foundational.27 Frascina is especially relevant to the present discussion, taking as his subject the multiple revisions Greenberg made to his well-known essay ‘Modernist Painting’, which was first written for a US Department of State-sanctioned Voice of America pamphlet in 1960, then revised for a Voice of America radio lecture broadcast in 1961, and reprinted many times subsequently. In it, Greenberg offers a structured way in which to understand American avant-garde painting as the heir to a legacy of modern art originating in Paris at the end of the nineteenth century. To his mind this was also the culmination of Western painting as a whole. Modernist painting, according to the critic, achieved such refinement through abstraction. Freed from the obligation to depict, an artist could pursue a true exploration of the medium. The lack of apparent content also signaled ideological independence, since abstract pictures necessarily also avoided an obvious political agenda. At the time this was a persuasive argument in favour of the free-thinking West, and an important booster for American civil liberties, given that the totalitarian regime in the USSR restricted the creativity of Soviet artists unless they were overtly in the service of the state. However, to return again to the paradox cited earlier: how could Greenberg argue that the greatest quality of American modernism is its ability to deflect politics, while at the same moment accepting money from the US government to promote its views internationally?28 To make matters all the more peculiar, in 1971 Davis recalled Greenberg’s praise of Washington artists’ relative ‘freedom’ from ‘political entanglements’, at precisely the moment in which the critic was deeply entangled himself.29

Before and during the Second World War, Greenberg argued for the importance of abstract art as a bulwark against the intrusion of both Nazi and Stalinist propaganda, since, he believed, the ‘true’ avant-garde sought a high standard of cultural quality purified of ‘ideological confusion and violence’.30 In the Cold War, the context, if not the criticism, had certainly changed. The US government amplified its persecution of communists within the US, resulting in infamous blacklists and witch-hunts – termed ‘McCarthyism’ after Senator Joseph McCarthy, who was the public face of the supposedly patriotic campaign. The attempt to contain communism resulted in a tight grip on culture. Hollywood, long known for its leftist sympathies, was especially hard-hit. Even greatly lionised foreign artists were subject to scrutiny. For instance, the Federal Bureau of Investigation maintained an active dossier on the French painter Pablo Picasso, surveilled him closely in Paris, and denied him a visa to enter the United States in 1950 because of his affiliation with the French Communist Party.31 As a result of this persecution, American leftist publications in the 1950s renounced socialist sympathies and became outwardly anti-communist. Major infusions of resources from the Central Intelligence Agency and the private sector shored up employment for intellectuals, trading their post-war disillusionment for cash.32

At the same time as the unexpected colonisation of the liberal elite by the staunchly anti-USSR American government, what Clement Greenberg saw around him in the 1950s was an incredible surge of US prosperity and an unprecedented consumer culture that pervaded every facet of American life. Of course, there were the cars, refrigerators, televisions, washing machines and massive, suburban, split-level homes, but also a spectacular art market with a newfound appetite for American-made products. The reification of Pollock, de Kooning and Mark Rothko within the context of late capitalism is now well-known to social art history: as the 1950s wore on, these artists’ names began to refer less to enigmatic painters of an intellectual avant-garde than to pieces of fashionable property.33 Overseas, the Marshall Plan was enacted as the official state foreign policy initiative, with the ostensible goal of flooding Western Europe with US dollars in order to modernise industry, restore European prosperity, and – of course – to expand the market for US products, in the hopes of forestalling the spread of Soviet communism.

Thus, the ‘ideological confusion and violence’ of authoritarianism that Greenberg saw in the Second World War and its immediate aftermath could just as easily have been applied to the new, insufferable institutional structures held up by the free market. Avant-garde art, then, derived its revelatory potential from its putative independence from its relationship to capitalism – or, at least its ability to conceal it. As Greenberg wrote in ‘The Case for Abstract Art’ in 1959:

[T]his seemingly new kind of art has emerged as an epitome of almost everything that disinterested contemplation requires, and as both a challenge and a reproof to a society that exaggerates, not the necessity, but the intrinsic value of purposeful and interested activity … and it seems fitting, too, that abstract art should at present flourish most in this country. If American society is indeed given over as no other society has been to purposeful activity and material production, then it is right that it should be reminded, in extreme terms, of the essential nature of disinterested activity.34

Here is the crucial point: the American government had a vested interest in the impartiality of Greenberg’s stance. If the essential character of American art was its resilience against political influence, then the government could claim its own impartiality to culture and distinguish itself from the vilified propaganda machine of its political rival, the USSR. If the political leanings of the artist are purified – as Greenberg insisted – by the transcendent art object as it hangs on the wall, then all ends justify the means. Frascina takes the question one step further: is this not also the logic of American Fordist systems of assembly-line manufacture, to erase the subjectivity of the worker in favour of the gleaming surface of the commodity?35

To Greenberg, the praiseworthy qualities of Louis’s and Noland’s paintings were their abilities to focus the viewer’s attention into a single point of visual concentration, requiring eyesight alone for their perception. Louis’s work, according to the critic, was so sensuously visual that it obviated the viewer’s every other sense to experience it.36 Noland’s did the same, although Greenberg was even more enthusiastic about the allusions his paintings made to space outside the canvas, an ambitious centrifugal radiation that nonetheless referred ultimately back to itself, the painting, as the centre and locus. Greenberg wrote: ‘One of the effects achieved was that of boundlessness, of anonymous and ambiguous space, and the way in which it specifies and at the same time generalizes … space, making it seem both very literal and very abstract.’37

Boundless, anonymous, ambiguous, general: these are words that describe power, specifically the power of a capitalist nation-state feigning its own impartiality to culture. Indeed, these are words about control and the consolidation of control in the Cold War. Late-twentieth-century expressions of power tend not to be found in a single person or ruling class, but rather in power structures supported by ruling class interests. Such power is diffuse, and the average person maintains an ambivalent relationship to it, because our everyday desires are invested at different levels in attaining power, either consciously or unconsciously; it is also these desires which make it very difficult, if not impossible, to resist submission to the power at the centre. In this sense, the policeman and the prime minister are one; they are the same.38

It is little wonder why the powers that were in Washington, D.C. in the early Cold War favoured Greenberg’s formulation of modernism. Enfolded within in it was a rhetoric of dominance that was not regional nor even national, but global in its scope and purpose. In effect, Greenberg had put the success of Louis and Noland down to their ability to harness the brutal force of this anonymous power, returning it to an object – a painting. However, as his interest in the apolitical nature of the avant-garde would prescribe, not even the painting existed in material form as such, but rather as an object for disinterested contemplation and the pure pleasure of visual experience. Truitt’s sculptures, since they physically occupied space, were less transcendent to the mind of the critic. Although he was otherwise a vigorous proponent of hers, Greenberg attributed what he considered the occasional weakness of her works to the artist’s ‘feminine sensibility’, revealing the masculine bias that typified the period.39

Davis’s specificity

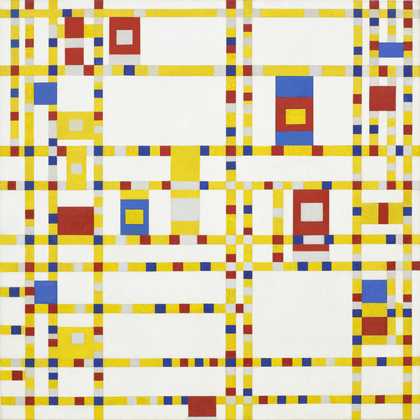

Fig.8

Piet Mondrian

Broadway Boogie-Woogie 1942–3

Museum of Modern Art, New York

As a critic, Greenberg chastened the local and particular. Take, for instance, Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie 1942–3 (fig.8), a surprisingly literal painting for the De Stijl artist, invoking the Manhattan grid filled with traffic lights exuberantly pulsing in continuous, syncopated rhythm. Greenberg, who otherwise celebrated Mondrian, disliked this painting – he thought it was a failure, calling it ‘floating, wavering, and somehow awkward’, to describe value contrasts weaker than in his older work, although adding that it was ‘a failure worthy of only a great artist’.40 But art historian Yve-Alain Bois suggests that rather than being about formal characteristics, Greenberg’s disappointment with the work had to do with Mondrian’s fetishisation of his new life in New York, having escaped war-torn Paris. For one, Mondrian painted by electric lighting rather than gaslight, which may have accounted for an unfavourable change to the overall effect of his colours. This was, namely, the unpredictable perception of secondary colours besides red, yellow, blue and greyscale (the ‘pure’ primary colours, so to speak). But then there is the plain fact of the jazzy grid – too much a representation to suit Greenberg; a tribute, even, to the local sights and sounds of Mondrian’s exhilarating new home.41

Local appeal was not Greenberg’s metric of quality. The closest Greenberg veered to this discussion came in a very long essay, often overlooked in the United States, entitled ‘Painting and Sculpture in Prairie Canada Today’, commissioned by the journal Canadian Art and published in the spring of 1963.42 The extreme isolation of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta led Greenberg to ‘take it for granted that prairie art was nothing but provincial’, ‘doubly provincial’, he wrote, because it was first isolated from the main cities in Canada, and secondly, isolated from Paris and New York. In the end, Greenberg describes his satisfactory impression of Canadian art and especially its landscapes, the distinctiveness of which he speculates is ‘owed to the character of its favorite terrain’. About fifty words later, Greenberg moved on, writing more characteristically about the Canadian modernists’ assimilation of French impressionism into the English landscape tradition.

It may seem now that we are at the furthest remove from Gene Davis. But keeping Greenberg’s disapproval of Broadway Boogie-Woogie in mind, and in general the critic’s ambivalence towards local representation, we might speculate that Greenberg found Davis to be too provincial in his references – too much a discernable product of a place and time in Washington. First of all, the attachment to Noland as a consequence of training in the institutions of Washington was too specific for the critic’s taste. He wanted Davis to paint like Davis – not Noland. Noland’s influence was so detectable, in fact, that Greenberg insisted upon an attribution; the critic irately contacted Davis to say that he had read an interview in the Washington Post Times-Herald, published on 26 August 1962, in which there was no sufficiently proper mention of the more famous artist. Davis followed up quickly to Greenberg that he had brought it up, but that it was the journalist’s decision to edit it out of the published piece and hastened to add that he would write a letter to the Washington Post to right the wrong.43

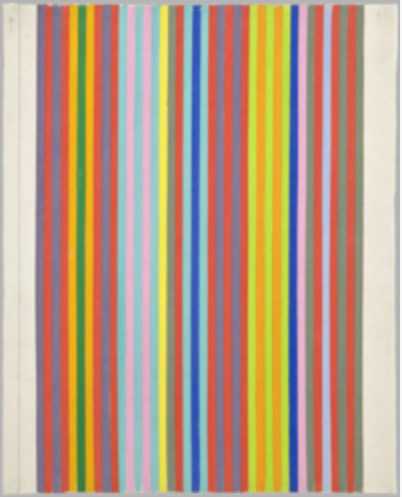

Fig.9

Gene Davis

Quiet Firecracker 1968

Tate T01116

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Instead of just looking at its contents, it is useful to examine the offending interview in the Washington Post as Greenberg would have seen it printed: on the left-hand side of the page is the interview, accompanied by the requisite photograph of the artist, looking appropriately artistic and attentively at work. On the right-hand side is a full-page advertisement for a sale at Sears Roebuck department store, featuring every single appliance befitting of the prosperous American Cold War home. I do not wish to suggest that seeing these pages side-by-side left any conscious impact on Greenberg, nor caused him directly to criticise Davis for being ‘flat-footed’ at his following studio visit. But, using Greenberg’s criteria, there is something provincial about Davis when seen against this backdrop, especially in comparison to Noland, Louis and Truitt. The painter’s colours veer into the cuteness of peppermint pink and toothpaste blue: colours pertaining more to kitchen tiles and retail displays and less to the measure of stately power that a proper Washingtonian’s art was meant to possess. Certainly, Noland and Louis (and Pollock and Frankenthaler before them) also had their pastel moments, but Greenberg stood by them as originals, whereas Davis was the product of a school. What was perhaps even more irritating to the critic was that Davis leaned into the ebullience of the open palette; the titles of the paintings he produced in the later 1960s reveal a sense of whimsy: Dr. Peppercorn 1967, Raspberry Icicle 1967 (both Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.) and Quiet Firecracker 1968 (fig.9), to name a few. The painter’s ‘provincialism’ in this instance connotes domesticity – appealing to the popular taste rather than standing apart from it; effusive but lacking in critique.

Naturally, Greenberg would not necessarily have taken issue with the triviality of titles or the hues they name, but he would have criticised Davis’s colourfulness as being a contemporary fashion rather than a formal quality made vital within a specific compositional context. We know that the critic’s distaste was not only born out of an objection to ‘kitsch’, as the art historian James Meyer explains, but also that collectors’ interest in faddish styles in the early 1960s had resulted from waning interest in abstract expressionism, the style that Greenberg so fiercely defended at its outset and the originality of which he continued to champion internationally.44 To evaluate the beauty of a style based on its marketability was at odds with Greenberg’s enduring belief in the forward thrust of modernism – the expediency of his criticism as it became more mainstream notwithstanding. This resulted in his problem with the Washington artists outside of the trio he designated as the originals: others were all too derivative, too imitative of a pioneering style that had already hit its stride; others were faddish and therefore moribund.

Finally, let us examine another alignment between Davis and Mondrian – their shared interest in jazz. Indeed, the syncopation of jazz music and its massive influence on American modernism is a history largely disavowed by Greenberg, whose agenda was instead to construct an illustrious lineage connected to the formalistic aesthetic revolutions which took place in Europe during the belle époque, the period at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. By 1971, Davis felt emboldened to admit freely to Barbara Rose that he was a ‘frustrated musician’ and that ‘painting stripes with musical intervals may be a kind of unconscious compensation for the fact that I never made it as a musician’.45 Curiously enough, Davis resisted a strictly percussive interpretation of his work, focusing instead on the juxtaposition of intervals – a rather Greenbergian revision. Notwithstanding this, Davis’s citation would not have ingratiated him to the critic in 1962, but a decade later the point was moot: Davis had hit his stride as an artist who went beyond the critical strictures of colour field painting. As Kee argues, by the end of the 1960s, his practice reached past the established style to invite certain aspects of pop and conceptualism – even performance art – to transform it. In fact, the artist’s eventual openness to that which was outside of Greenberg’s mandate kept Washington’s art dynamic beyond the era of the Color School.46

Fig.10

Gene Davis

Study for Franklin’s Footpath 1972

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Davis’s ‘boogie-woogie’ was his refusal – reluctant at first but more confident over time – to conceal or sublimate his work’s pedestrian qualities. His paintings’ ebullience through the 1970s resulted in an even greater appeal, leading to invitations for important public commissions in New York and his most famous project, Franklin’s Footpath 1972, a two-block-long painted stretch of striped colour situated on the ground outside the Philadelphia Museum of Art (see Study for Franklin’s Footpath; fig.10). These larger commissions had the positive effect of allowing Davis to pursue his art-making fulltime, and it no longer mattered what Greenberg advised. In a sense, the enduring popularity of the Washington Color School derived from a quality that the critic overlooked; as these artists retreated from the embattled politics of the war years they became, in their heyday, audaciously responsive to ordinary experience.