My participation in the exhibition implies my personal presence for a reasonable period of time … my interest in the exhibition is in my permanent presence … When I have to be absent the blackboard would stand for my presence.

Joseph Beuys1

The concepts of presence and subjectivity are inextricably linked within the work of the German artist Joseph Beuys, and the viewer’s confrontation with Beuys’s presence was arguably never more evident than when he participated in the exhibition Art into Society – Society into Art: Seven German Artists at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in 1974. The exhibition offered the possibility of examining Beuys’s visual, verbal and textual manifestations through both the exhibition space and the accompanying catalogue, in order to uncover inscribed issues within his work surrounding the artist’s presence. The photographic representations of the artist at work that were published in this catalogue, together with the inclusion of three text-based documents by Beuys that appeared there in English for the first time, ensured that Beuys’s presence operated on several levels.2

Art into Society – Society into Art: Seven German Artists (hereafter Art into Society) took place at the ICA between 30 October and 24 November 1974. It was part of a ‘German month’ held in London, supported by funding that became available when Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973, and was curated by Christos M. Joachimides and Norman Rosenthal. It brought together a diverse group of seven politically engaged German contemporary artists – Beuys, Albrecht D., K.P. Brehmer, Hans Haacke, Dieter Hacker, Gustav Metzger and Klaus Staeck – and provided an arena in which their work could confront a British audience.3 The promotion of these artists within the format of a group exhibition suggested the articulation of a collective aesthetic, one which was thematised through their shared nationality and one which had been explored the year before in an earlier iteration of the show held in Hannover.4 This shared aesthetic or set of concerns was drawn together in the ICA show through the ideas of subjectivity and presence, with each of the artists reflecting these two concepts against the backdrop of the international politicisation of art during the 1970s. These concepts were of interest to Joachimides in his wider curatorial work and the role of the artist’s presence was also referred to in the wider promotional material for the German month.5

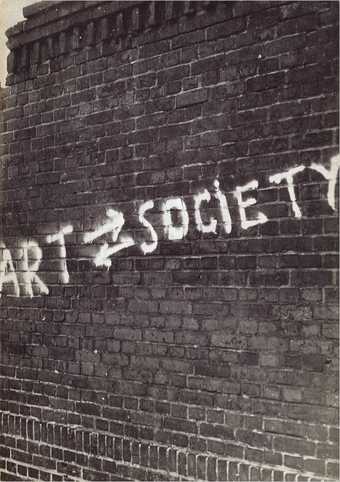

Fig.1

Cover of the exhibition catalogue for Art into Society – Society into Art: Seven German Artists at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1974

It could be argued that the 1970s was a crucial decade for the exploration, both thematically and physically, of the non-existent or non-visible relationship between art and politics, as well as the fallout from the turbulent end of the 1960s, when mass protests against repressive political regimes were staged across the world, especially by students and workers. Beuys’s work in Art into Society drew attention to his refusal to accept this status quo and his desire to articulate the non-material, or dematerialised, presence of the relationship between art and politics.6 On a wider scale, it was precisely this idea of an enforced absence (or even non-existence) of political or social motivation in art that Art into Society as a whole sought to dispute – an aim articulated on the exhibition catalogue’s cover through the graphic arrow symbol suggesting a two-way channel between ‘art’ and ‘society’ (fig.1). This paper will show that, as well as undermining readings of Beuys’s art that regard it as wholly individualistic, the exhibition highlighted the impossibility of an absolute distinction between absence and presence, through the contributions of Beuys, his fellow participating artists, and the exhibition catalogue itself.

A dual presence

The notion of presence can be measured in two ways in connection with Art into Society. Specifically, a duality can be established between the catalogue on the one hand and Beuys’s performative identity on the other. The real experience of this duality is through the combined confrontation with Beuys in person, as the subject present, and the Beuys that is seen through the catalogue photographs, who is simultaneously absent and present. The catalogue element can be understood in light of several other printed works that Beuys made in the 1970s, in which he used personal narrative that was deconstructed and reconstructed in the work. This can be seen, for instance, through the structural interaction of his works Joseph Beuys Lebenslauf Werklauf 1964–70 and Arena – Where Would I Have Got If I Had Been Intelligent! 1970, 1972–3, and the further connection between these two works in the book multiple Die Leute sind ganz prima in Foggia 1974. Lebenslauf takes the form of an annotated biography, while Arena is made up of a collection of photographs of Beuys’s works and performances and is an autobiographical visual record. Die Leute sind ganz prima in Foggia amounts to pieces of paper pasted on each of its seventy-five pages. The pages present various phases from Beuys’s Lebenslauf and his actions. These pieces of paper are not presented in chronological order – a key feature of Beuys’s autobiographical practice.

Fig.2

Joseph Beuys participating in a discussion in Basel, 1971

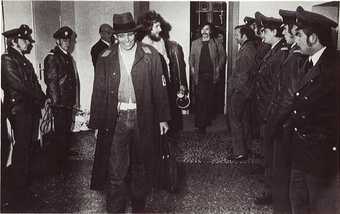

Fig.3

Police escorting Joseph Beuys out of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf following his dismissal from his teaching post, October 1972

This use of narrative construction and deconstruction, as well as the questioning of representation and the fixed status of the subject, was further seen in the exhibition catalogue for Art into Society, which included five powerful photographic images of Beuys at work. The first image confronts the reader with the well-known incident at the Technische Hochschule Aachen in 1964 in which Beuys was physically assaulted by a spectator during his performance. The photograph shows Beuys with an expression of pure defiance on his face, blood streaming from his nose. The second image was taken at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1967 and shows Beuys drawing with chalk during a meeting of the Deutsche Studentenpartei – the political party that he co-founded in 1967. The third shows Beuys taking part in a discussion in Basel in 1971 (fig.2); the fourth records Beuys’s boxing match against A.D. Christian-Moebuss on the last day of Documenta 5, 1972; and the fifth and final image shows the notorious incident in 1972 when Beuys was escorted out of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf by armed guards following his dismissal from the role of Professor of Monumental Sculpture due to unacceptable behaviour (fig.3).7

At the time of Art into Society, these images had not been subject to the same degree of dissemination within the literature on Beuys that they have since achieved, and their place within the hype surrounding Beuys was very different in the 1970s.8 The exhibition and the catalogue images echoed a duality often seen within Beuys’s work between the Dionysian (chaotic, instinctual) and the Apollonian (logical, rational): this can be seen in the unpredictability of the action pieces as compared with the order and precision of the photographs. It is the fusion of these two elements – the performance (Dionysian) and the catalogue (Apollonian) – that accounts for the balance between order and chaos in Beuys’s presence in the exhibition itself, and for what philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche called the Kunsttrieke (artistic impulse).9 In what follows, this dual mode of confrontation will be discussed via the dialogue established during the exhibition between Beuys and German artist Wolf Vostell, here regarded as Apollonian in intent, and Beuys and Romanian artist Paul Neagu, here cast as Dionysian in intent. The status surrounding Beuys’s presence in the 1974 show will be examined in relation to his visual, verbal and textual presence through the catalogue format and his direct encounter with Neagu during the exhibition itself, using this to discuss the issues surrounding presence that are inscribed within Beuys’s work.

A dialogue with Paul Neagu

The emphasis that Beuys placed upon the idea of permanence and the importance of his physical presence during Art into Society is perhaps more revealing of his circumstances in 1974 than even he was aware. Permanence was not a state that many would have associated with Beuys at this point in his career; for Beuys, the 1970s was a decade of increasing international mobility and arguably self-promotion.10 During the exhibition Beuys visited Northern Ireland twice and incorporated the exchanges he experienced there into his subsequent dialogues. He was also starting to embrace America at this time, visiting for the first time in January 1974 and returning again in May of that same year. This travelling was part of the broadening concept of Beuys’s ‘social sculpture’ – his idea that life itself is a sculpture and every person is an artist whose actions contribute to this collective artwork. It was also part of his need to be both seen and heard coupled with an instability on Beuys’s part as to where to place himself artistically. It was perhaps this desire for permanence as a state of being, and as symptomatic of his serious political aspirations, that caused him to distance himself from the loosely Fluxus-associated work he made over the previous decade, such that the year 1974 was a turning point in Beuys’s career.

Fig.4

Heinrich Riebesehl

Joseph Beuys photographed after being struck by a spectator during his performance Kukei/Akopee-nein/Browncross/Fat corners/Model fat corners at the Fluxus Festival for New Art, Technical College Aachen, 20 July 1964

© Heinrich Riebesehl

To some extent the reception of Beuys, politically and aesthetically, at moments during the 1960s and 1970s was triggered by a provocation or confrontation of some kind. Beuys’s art was nothing if not divisive, and the interpretations of his work by artists and those in positions of power made him one of the most controversial artists of the post-war generation. Art into Society was no different in this respect. That this notion of provocation underlies the ICA exhibition is supported by the five images chosen for the accompanying catalogue, particularly the images capturing Beuys’s participation in the Fluxus Festival for New Art, Aachen, 1964 (fig.4). Art historian Gene Ray has provided a detailed description of this incident, in which Beuys was performing Kukei/Akopee-nein/Browncross/Fat corners/Model fat corners:

Details about the evening-long performance as well as the precise sequence of events are sketchy, but Beuys himself relates that he turned on the burner and melted a block of fat in an action called Kukai. While the fat melted, a collaborator recited the text of the notorious 1943 speech of Nazi propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels at the Berlin Sportpalest in which he demanded rhetorically, ‘Do you want total war?’ Apparently, it was at this point or shortly after that Beuys was struck.11

Beuys was attacked by students who interpreted his action as being in some way complicit with atrocities under the Hitler regime, and the artist was charged with inciting a riot; the charges were subsequently dropped due to the intervention of the German Ministry of Culture and Beuys’s colleagues at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. However, this occurrence would have far reaching consequences for Beuys, in that as a result the Ministry of Science refused him a permanent position in the teaching faculty of the academy. This meant that Beuys, the future spokesman for the proletariat, was himself only a ‘public employee’, and as such subject to a quarterly notice period and denied the security of a permanent position.12 In one respect, therefore, permanence was an ideal yet to be achieved; prior to this moment in 1974 it had eluded his grasp.

Beuys’s seeming dedication to his physical ‘permanent presence’ in London in 1974, as revealed in the opening quotation, was also tested in very real terms during the course of the exhibition itself via his encounter with Paul Neagu. In 2001 Neagu provided the following recollection of their encounter:

What happened was a single point of contact, because Beuys as usual was writing half German or actually mostly German on the blackboards. He was talking at that precise moment about the half cross, Eurasia and other related concepts … At some point I approached him, surrounded by my group of students, and the circle of spectators around Beuys became very small. Why? … Because Beuys will never come up in the audibility of his voice, so I approached him and said: ‘Excuse me but can I interrupt you?’ Beuys replied: ‘Yes please say.’ So I started to say something to him that was very damaging. ‘Joseph Beuys you have been standing here with your stick in order to demonstrate something. I don’t understand why you have to do that? You are standing on your boards after you have fixed them with a spray and then throw them on the ground to make a big bang. Is this a show or lecture or both of them?’ To which Beuys replied: ‘It is both: it is my show.’ [I said:] ‘What you are saying here, do you think that you are the only one who knows how the world is to progress or how the individual situates themselves within the context of a society or what that should mean in terms of how a society is run according to a methodology?’ I was a bit aggressive but I wanted to irritate him. Beuys’s response was: ‘OK so you think that you can do it?’ ‘Yes I can do it at anytime.’ So Beuys took a clean board and put it on the easel and handed me a piece of chalk. I started writing and talking … when I had finished I did a gesture with the chalk and took the sponge and ran it over the blackboard and said: ‘I don’t want you to keep the blackboard. It is not an artwork. It is just an example of my furious verbalism. OK now if you want to finish the argument then please leave your baton and this spot and come to the café and we can sit down and talk about this.’ Beuys had indicated that he wanted to discuss certain points. ‘No I can’t go to the café. I am part of the show and I cannot leave the place, I am part of the environment.’

I replied: ‘When you gave me the right to say things I understood it as a debate and as a dialogue, so let us do it properly.’

Beuys said no, so the endurance test was his. So for him it was only an interruption. So as if nothing had happened he put another blackboard on the easel and continued.13

This confrontation between the two artists is revealing on several levels, but particularly for Neagu as he singles out Beuys’s use of language, rather than specific gestures alone, as a major factor influencing his own response. The unclear separation between teaching, action and Beuys’s demand for attention (‘this is my show’) acted as a provocation for Neagu. Furthermore, if, as Neagu points out, the language that Beuys was using was indeed German, then for an English-speaking audience this could result in an additional aspect of alienation that could combine with his esoteric combination of symbols and words to exclude them from Beuys’s theories. One could therefore claim that Neagu’s issue with Beuys lay in Beuys’s positioning of himself as apart, principally in terms of a failure to articulate a systematic theory, linguistically and thematically – a distancing that was also felt by Neagu in physical terms when he noticed the distance between Beuys and the spectators. Beuys’s closing down of a dialogue and his failure to resolve this confrontation with Neagu seemed to aggravate the situation still further.

The specific controlling of his physical space and the desire on Beuys’s part to keep the audience at a distance, withholding certain elements both of himself and his works, was already present in his early performance pieces such as The Chief (Der Chef). This performance took place at the René Block Gallery in Berlin in December 1964, five months after Beuys’s controversial appearance in the festival in Aachen. The larger of the two spaces in the basement at René Block Gallery had been set aside for Beuys, while the smaller one was occupied by an installation by Robert Morris. The connecting doorway between the two gallery spaces was used by Beuys as a barrier to vision, to interrupt or defer the public’s gaze during his performance. He did this by directing the audience into the second room containing Morris’s installation, from where they observed Beuys’s performance. He achieved his desired effect further by hanging a piece of cloth in the doorway that, although it was transparent, obscured the audience’s view.14 As such, the space in which Beuys performed was never breached physically by the spectators.15

If we consider this control of space by Beuys following his earlier performance in Aachen, then one could see it as a specifically reactionary gesture. Having been physically assaulted and having had his personal space violated in the performance in the earlier event, he was no doubt reluctant to encourage a repeat of this incident. However, I would argue that the link between The Chief and Beuys’s later works such as the ICA exhibition and its catalogue revolves around his concern for framing the space in which action occurs, and is therefore not merely reactionary. Further evidence for this is Beuys’s behaviour at a John Cage performance at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1964: here, Beuys physically locked the doors during the performance and refused the students exit, describing this as comparable to reliving nights spent in bomb shelters as a child.16 Critic Jan Verwoert, whose mother Elfi Weimar was present at the event and recounted these details, regards Beuys’s control of space as an authoritative gesture.17 In Beuys’s refusal to leave the space of the exhibition during his encounter with Neagu he further controlled not just his own space but the space of others.

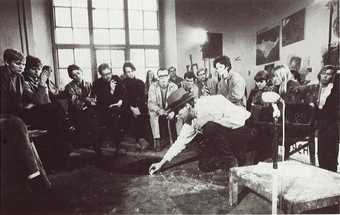

Fig.5

Joseph Beuys with his blackboards on the gallery floor in Art into Society, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1974

Returning to Neagu’s challenge to Beuys, we could consider Beuys’s use of language, in this case German, as reflecting a desire for a physical effect through his interaction with the audience, perhaps instantiating the familiar element of provocation found within his work. This desire is further evinced through the physical presence of the blackboards themselves. During the exhibition these blackboards containing Beuys’s thought processes, scribbled in chalk and sprayed with a fixing solution, were swung by Beuys down onto the floor (fig.5). In his absence from the exhibition space the boards were walked upon by the audience who engaged with Beuys’s use of language in a very physical way – something that he had encouraged them to do. This way, they could also leave their own mark or contribution in his absence.18 Within the social sciences the origins of language are placed within a distinctive set of rules belonging to social actions and social institutions. Could this provide a framework for Beuys’s use of language here, and his potential subversion of these rules? Philosopher Peter Winch has argued that within the social sciences, the questions that revolve around the definition of meaningful action – here the placing of the boards onto floor – are themselves embodied in language: ‘Our language and our social relations are just two different sides of the same coin. To give an account of the meaning of a word is to describe how it is used, and to describe how it is used is to describe the social intercourse into which it enters.’19

To speak of ‘social relations’ is to enter into a dialogue with Beuys and his idea of ‘social sculpture’, a concept that entered his discourse in the 1970s and marks a departure from his work of the 1960s. As mentioned, social sculpture refers to the idea that lived experience is a sculpture and that everyone’s actions contribute to this collective artwork. Yet to what extent was Beuys’s idea of social sculpture as a theoretical model tied to a prescribed notion of language? Speech and language were an integral part of Beuys’s artistic production, where words were seen as a malleable substance similar to the materials of the sculptor. For Beuys, language, or to be more precise, speech, served as the medium through which he acknowledged the delimitation between the norms of society and the intersubjectivity of language within everyday life, both of which are relevant to the concept of the ICA exhibition space, in that Beuys controlled both his speech and his surroundings through these means.20 Where Neagu and Beuys do align is in the recognition that it is this very use of language and speech that is paramount, with Beuys stating that ‘As the idea of speech was from the beginning very important; that I was conscious, that speech itself is sculpture.’21

In the ICA exhibition, this connection between language and sculpture and the definition of social sculpture was systematically ordered through Beuys’s manipulation of language. The blackboards that Beuys used during the exhibition therefore become the transmitter for these theories. As art historian Claudia Mesch has argued: ‘By 1971, the blackboard comes to function for Beuys as a document of the course of collective thought with the fluid process of open discussion … Even within an academic setting, the board marks the flow of public discussion and traces intersubjective dialogue, the process of give-and-take between individuals as they move cognitively through certain complex ideas.’22

That it was within the ICA catalogue for this exhibition that Beuys published his essay ‘I Am Searching for Field Character’, in which the term social sculpture first appeared in a concretised written form, suggests that our introduction to this working methodology required the presence of Beuys in order for us to understand it.23 The catalogue itself was insufficient as a tool for explaining social sculpture; Beuys’s physical explanation was required through his presence in the exhibition space. Yet Neagu found this to have failed, since Beuys’s presence for him provided no further understanding of the artist’s methodology.

Beuys’s use of the term ‘conscious’ in the sentence quoted above is significant in that it serves to reinforce the themes around which the ICA exhibition revolved, namely the interaction of the visual and the verbal and the transition from the one to the other within Beuys’s work. What is being suggested here is that in his use of the term ‘conscious’, Beuys pointed towards an understanding of his place at the ICA as part of a calculated gesture. Although the nature of his physical presence and the lecture presentation allowed for a certain sense of spontaneity, with Neagu’s interaction being but one instance of this, the exhibition space was as much a controlled environment as were the catalogue pages.24 Hence the photographs included within the catalogue to some extent function as a tool of propaganda and self-promotion for Beuys. It is no coincidence that Beuys’s participation in the ICA exhibition was itself part of a campaign trail that stretched from Scotland, England and Ireland to America. We are then dealing here with a certain form of self-consciousness that reflected Beuys’s hopes of being able to transfer one political system – that which he had co-founded within West Germany – to an alternative political system – that of the United Kingdom and Europe as a whole.25 However, in the context of Art into Society, this aim arguably became confused through Beuys’s use of German, a language that was not native to the audiences he was addressing.

Metaphor and ideology

Beuys placed an emphasis on metaphorical language as a political rule of engagement, and as such metaphorical language is instrumental in the understanding of Beuys’s political theory. Although initially comical in their effect, Beuys’s references to the expertise and structure of alternative forms of work and life – key examples being the farmer or animal/insect life – all operate as poetic expressions of basic presuppositions about political reality, which in turn, are characteristic of Beuys’s political thought.26 Political thought is certainly no stranger to metaphor, with ancient Greek political philosopher Plato being a guiding force for Beuys, but it is often regarded with suspicion; metaphorical language allows for deception.

However, the general predominance of metaphor within Beuys’s discipline is crucial as a way in which we can attempt to understand Beuys’s political theory. If sculpture in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s transcended the limits of its own practice, as was argued by critic and art historian Rosalind Krauss, among others, then one could consider that this transcendence was redoubled through Beuys’s use of metaphor.27 For instance, when Beuys challenged society to Show Your Wound in an installation of that name created in Munich in the same year that Art into Society was held, he consciously revealed that this use of metaphor was both about self-healing and about drawing attention to problems within society as a whole. This is one way in which he could be seen to transcend not only sculpture and language, but also the viewer themselves, as they search for a translation – leaving audience members such as Neagu nowhere to go to find one.28

The extent to which Beuys draws on the power of language to mobilise a collective response is itself socially, if not politically, motivated. This tendency to associate metaphor, ideology and revolutionary political objectives has its origins in a desire, rooted in the thought of seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, to expel socially disruptive terminology from scientific political theory as a whole. Although one would warn against reading into Beuys’s usage any systematic manifestation or influence of a certain strain of ideological thinking, this does not necessitate that we ignore its manifestation in all its various forms in Beuys’s work. Metaphorical language in one form or another is commonly deployed by artists, but what is significant about Beuys’s contribution to Art into Society is the extent to which, through the incorporation of the blackboards, this metaphorical language was perceived as an obstacle to be overcome.

It was this concern with the purposes for which Beuys employs these metaphors that gave his detractors such food for suspicion.29 Metaphors can be manipulated so that what is problematic and unclear can, with the use of a metaphorical substitute, become self-evident, and it is this use of metaphor that is so important to our understanding of Beuys.30 Metaphors are also primarily pictorial representations and it is through their capacity to operate as such that the pictorial emerges in Beuys’s work. In addition, metaphors are peculiarly positioned as a means through which we can penetrate other levels of consciousness, appealing to memories or life experiences stored in the recesses of our being. The consideration therefore of the patterned metaphor within Beuys’s work – his adherence to repetitive signs and symbols – reveals something of the level of his consciousness and intention, including its use by Beuys as a form of self-protection from direct assaults on his language.

This detour through the language of the metaphor provides us with concepts through which we can begin to comprehend Beuys’s use of language in Art into Society. What is being referred to here is not only Beuys’s own use of language, but also the language of promotion surrounding Beuys’s participation in the exhibition itself. For instance, a press release that was issued in connection with the German month at the ICA in October 1974 spoke of Beuys in very specific terms as: ‘Probably the most significant post-war German artist, an outstanding sculptor and as the ICA exhibition will demonstrate, outstanding draftsman.’31 This attempt to locate Beuys within the professional categories of sculpture and draughtsmanship becomes difficult when we consider the form that his involvement took at the ICA. While the blackboards occupy a space that straddles the sculptural and the drawn, attempting to address Beuys’s contribution in these narrow terms threatens to undermine what it is they were intended to achieve.

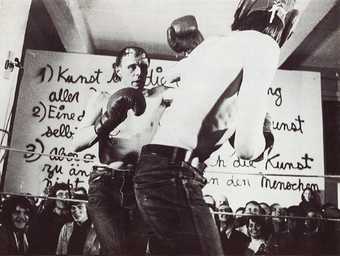

Fig.6

Joseph Beuys and A.D. Christian-Moebuss in Boxing Match for Direct Democracy through Referendum at Documenta 5, Fridericianum, Kassel, 8 October 1972

Fig.7

Joseph Beuys at a meeting of the Deutsche Studentenpartei, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, 1967

In F.R. Leavis and Denys Thompson’s research into the advertising industry, they speak of the ways through which modern advertising is justified in economic terms by its function of bringing knowledge of desirable merchandise to consumers.32 Following this logic for the consumer of Art into Society, the merchandise that is available here is neither Beuys’s sculptures nor drawings but rather his presence, words and visual photographic images. Almost as if to challenge the growing recognition that as consumers the public were becoming more and more alike in their consuming habits, the photographs offer a choice of consumption, as we are invited to buy into any one of the representations that Beuys offers us: the boxer (fig.6), teacher (fig.7), anarchist, martyr. While the power of the visual manifestations is apparent, it is through their combination with Beuys’s use of language that the question of consumption within this exhibition is addressed. The show’s success revolved around the extent to which the spectators unconsciously bought into what Beuys both said and represented, which, as we have seen with Neagu, was achieved with some difficulty.

Beuys and Vostell

The dialogue established between Beuys and Wolf Vostell during Art into Society was perhaps indicative not only of the nature of the exhibition as an assemblage – as a process of organising participating artists – but also returns us to the flip side of presence, namely absence. While both Vostell and Beuys had been included in the Hannover exhibition Art in the Political Struggle the year before, Vostell was not part of the London show, though his work was included in its catalogue.33 The engagement between Beuys and Vostell was therefore absent from the exhibition space itself, but it occurred in printed form in the catalogue through the contrast between the photograph of Beuys in Aachen performing the Sieg Heil gesture associated with Nazism (see fig.4) and Vostell’s photographic screenprint German Students’ Wallpaper 1967 (fig.8).

Fig.8

Wolf Vostell

German Students’ Wallpaper 1967

Arts Council Collection, London

© 2019 Wolf Vostell

The decision to construct a juxtaposition between these two artists within the catalogue via these two images – whether consciously or not, and albeit separated by three pages – created a powerful statement on physical aggression within contemporary student culture. Curiously, these images appear united by the violence and martyrdom that their protagonists convey. In Vostell’s photographic screenprint German Students’ Wallpaper, we see the headline of a German student newspaper and the image of a female student whose hand is held to her head in an attempt to stem the blood pouring from her open wound, typifying the many images of violence in post-war France and Germany.34 The preoccupation with the theme of violence and insurrection – especially when levied at the face or head – through the newspaper medium not only speaks of a relationship between Vostell and Beuys, but establishes a certain continuity of medium and subject matter in other works produced by Beuys in 1974.35 The choice of Vostell’s imagery here is significant, as perhaps no other single photograph could better typify the turbulent and violent times worldwide throughout the 1960s, the consequences of which were still being felt in the 1970s and resulted in Beuys’s own propulsion onto the international art scene.

Beuys and Vostell’s works are framed by the historical remembrance of the students’ and workers’ protests that took place across the world in 1968. These were seen in part as the catalyst for the rise of political insurrection within Southern Europe during the 1970s. While one could claim that this is precisely how both images operated in retrospect, this is not their sole function. The images operate as a moment of dialectical presence, in that both images serve as a contradictory presentation of opposing viewpoints. Vostell described his career as having begun with the student movement of 1968, so the violence we see in German Students’ Wallpaper contains within it an origin story.36 Political theorist Fredric Jameson commented that ‘We are now far away enough from 1968 to have realised that the media personalisation to which [sociologist Erving] Goffman refers was not so much the sign of some impending social transformation, as rather a mode of containment in its own right’, making an interesting point concerning the cultural suture caused by 1968 in terms of the fate of the individual subject. This suture could encompass both Beuys and Vostell’s images as well as the wider impact that newspaper and media culture had at this time within artistic practice, in particular through the insurrection of the photographic.

The formal presentation of the two images that are our focus here is not itself the means of achieving a social or even a cultural transformation. However, what it does is ‘contain’ (to borrow Jameson’s term) the mood of the moment that reflects the shared theme concerning the scenes of student unrest. Both artists, either by instinct or design, offer their own strategic approaches towards capturing this mood and the associated complex issues it involved; yet through the historicisation process, these works no longer appear as a direct consequence of the problems faced by the student population at that time. This raises the question of to what extent both the photographs and the montage format used in this instance are more and more disempowered the further away in time they are from the historical event. The specificity of the photographic moment for both artists is lost in the generality of time. While in the case of Beuys the connection with university reform took a more pronounced and personalised form, one would still have to argue that both artists’ works or outbursts cannot be seen as orientated solely towards educational change, but more specifically towards sociological or political change.

It is clear that Beuys’s privileging of the newspaper in his material production, when understood within the climate of political radicalism of the mid-1960s and the 1970s, occurred as part of the general recognition of the complicity of media coverage in the promotion of a version of a counter-culture. This moment of breakthrough in the media industry coincided with the recognition and reception of Beuys, as well as with the deterioration of his relationship with Vostell.37 A change in syntax occurred within the newspaper and poster industry during the 1960s and 1970s, with the media shifting orientation towards individual personalities. The promotion of Beuys at this time forms part of this syntax and was symptomatic of the media’s palpable desire for the personalisation of leadership and invention of political slogans and catchy soundbites rather than systematic theories and well-rounded arguments. It was this reality that became subject matter for artists of this time. There was an increase in the number of what within Germany were called ‘pseudo events’ – symbolically mediated events, experienced retrospectively as artworks rather than directly, which targeted an unseen audience as opposed to a ‘present’ audience. This took on a more pronounced form with the Springer Press, which combined its conservative attitudes with an exaggerated publicising of the radical bombings carried out by the West German far-left Baader–Meinhof group from 1970 onwards. The media endorsement for the counter-culture that saw the translation of action into violent terms during the early 1960s therefore to some extent ensured that it was to be a violent act that formed Beuys’s inauguration into the media spotlight. This move towards violence is simultaneously reflected in Vostell’s choice of imagery and his treatment of it using the montage format.

The use of repeated media tactics encouraged, and continues to encourage, a widespread misunderstanding surrounding the true meanings and importance of Beuys’s event at Aachen, and typifies this particular characteristic of the publicity machine. Beuys’s rise to fame, when understood in the context of the mid-1960s, took place within an environment in which political radicals were prepared to accept the necessity of media coverage in the promotion of their version of counter culture. There are various readings of the Aachen scene that have attempted to account for and justify the reaction from the student as being the result of an inability to understand what Beuys was trying to achieve. In these accounts, the student’s behaviour is dismissed under the protective shield of ‘incomprehension’, as well as the immaturity of youth and the suggestion that the student was rebelling against Beuys’s authority.38 It could be argued that Beuys’s image replicates the thematic of obvious confusion and the register of shock that is seen on the face of the student within Vostell’s own work. Vostell had actually been present during the incident at Aachen and there were reports of his involvement in the violence itself.39 However, to focus on the thematic of confusion contributes to the mystery surrounding the cause of the violent act and threatens to use this mystery as the way in which to empower the stance taken by Beuys as the figure of the misunderstood avant-garde artist. It is the registration of incomprehension that visually and conceptually forges the link between these two images and serves as part of this climate of ‘ressentiment’ (resentment towards authority), a moment in which Beuys entered the international arena as part of the German Fluxus movement, which also included Vostell.40

Repetition and trauma

The ways in which Beuys used his presence in his work during the 1960s and 1970s points to the opposition between public and private space, and it is important to consider how Beuys and Vostell approached these spaces. The title chosen by Vostell, German Students’ Wallpaper, refers to the work as a pattern for decorating walls. This suggests a violation of sorts: the invasion of the private space of a German student’s bedroom. In his use of newspaper as the material for his artistic practice, Vostell breaches the divide between the consumer item and the artwork in a way that Beuys does not. Yet the repetition of the image in German Students’ Wallpaper, appropriated from the front page of a student newspaper, establishes a thematic continuity with Beuys, in particular in the image of Beuys taken at Aachen.

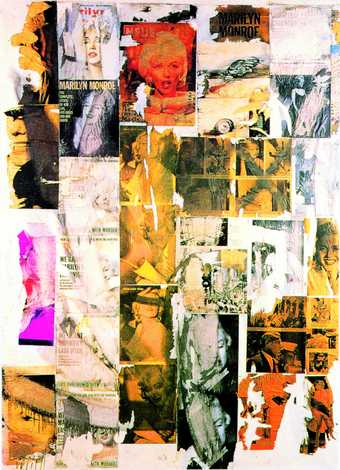

Fig.9

Wolf Vostell

Marilyn Monroe 1962

Private collection

© 2019 Wolf Vostell

In an earlier décollage piece by Vostell, Marilyn Monroe 1962 (fig.9), we once again encounter the serial format. Whereas with the image of the student we are presented with an unknown identity, here we have Marilyn Monroe, the epitome of the media personalisation process of the 1960s. Yet the décollage technique in itself is violent in its implications for the status of Marilyn’s identity. Vostell does not so much play with her image but rather subjects it to a form of violent ripping that ruptures the very fabric of her selfhood. This is further complicated through the aspect of the memorial, in that it is unclear whether he is respectful of her image or critical of it.

To return to Vostell’s image of the student, the more specific question this work poses concerns the effect that the repetition of such an image would have on the viewer. What does the strategic use of repetition do to the image and our understanding of it, and can this be seen to act in contradistinction to the more formal adherence to notions of seriality associated with American minimalism? For both Vostell and Beuys, the singular image loses its autonomy through the serialised format, and with it is lost any adherence to power and status as such. Almost as a reverse situation of the media personalisation process that reifies the image through repetition, Beuys and Vostell present an alternative fate of the subject through seriality – one that challenges the power of the autonomous image within society. For Vostell the fate of the individual subject is invoked through the idea of process, specifically the printing process and the constant production of images which calls into question the capacity of the singular image to function clearly and informatively. If, as we can see, the traumatic effect of the situation is written across the student’s face, then the repeated, unbroken chain of the serialised image, the lack of a seizure, rip, tear or rupture, ensures that we are at a loss to pinpoint what philosopher Roland Barthes would describe as the work’s punctum – an unexpected detail that draws the viewer into the image.41 In the absence of this, we are instead confronted with a visually traumatic serialisation that compounds the traumatic social reality to which the image makes reference. The serial repetition of outbreaks of violence within universities worldwide is endorsed through the serial imagery in both artists’ works.

Trauma functions differently within the two works by Beuys and Vostell. In Vostell’s photograph the student’s face is shown in profile, such that the relationship with the viewer is less direct. The anonymity of the student as the subject matter when combined with her formal treatment as an image negates the autonomy of both subject matter and artwork. By using the image serially, Vostell has ensured that the reader’s awareness is raised as to the social reality that permits that these occurrences are repeated. While the timing of the event is itself specific to its moment, by treating the image in this way, Vostell undermines its temporal specificity.42 By contrast, the moment caught on camera with Beuys is the moment after the event; there is no before or during but only an after, which is the construction of his response. Vostell’s image serves as a tacit rebuff of the staged response that Beuys adopts towards the infliction of violence. In the rejection of specificity, Vostell’s message is deliberately indirect: it is not about capturing a moment in time, but rather the culture of violence itself.

It is Vostell himself who draws attention to the dialectic of both revealing and concealing, both in terms of his own treatment of the newspaper imagery through montage and in his indictment of Beuys’s visual practice. In his commentary on Beuys’s performance piece The Chief, Vostell highlights Beuys’s attempts to conceal his visual presence as a performer, registering his presence instead through acoustic amplification.43 The images seen within the ICA catalogue visually fluctuate between the notion of exposure and the state of composure. Any temporary loss of control on Beuys’s part has been overcome and he appears victorious in the regaining of his composure and control. However, over whom is Beuys victorious here – the student who represents the university, and as such is both part of the very institution that Beuys wished to challenge and simultaneously part of the youth movement he reached out to as the symbol of change for society? To what extent the elements of the performance were the result of an impromptu decision on Beuys’s part we cannot be sure, but the tendency within critical circles to misinterpret its meaning is revealing.

It is Beuys’s desire for control that unfolds throughout the series of photographs in the ICA catalogue and which Vostell’s inclusion within the publication serves to highlight. The public image of Beuys represents an attempt on his part to flirt with danger and possibility of losing control: the boxing match during which Beuys is not at risk of physical injury; the scene in which he is engulfed by the audience, a mass of chaotic energy which Beuys attempts to channel through his body; and finally his eviction from the university in Düsseldorf in the presence of armed guards. All of these images have one thing in common in that they present Beuys as the centre of attention. The insertion of the viewer is implied, whether through their participation, as captured photographically, or through their implied absence as the reader/viewer of the image. The photographs can be said to function narcissistically in that they are intended to operate as a form of identification with the reader as an extension of Beuys himself; as such they serve a distinct purpose when compared with Vostell’s own critique of the role of the individual subject. With both images, the substitution of the real event for the symbolically mediated photographic information about the event formed two different statements concerning the balance of power and the artists’ responses to it, and also revealed where they placed themselves physically in this dialogue.

A strategic mode of enquiry into socio-economic concerns and their articulation within the field of artistic practice was posed collectively by the artists participating in Art into Society. It could be argued that Neagu, as both artist and spectator, contributed to this same process. The exhibition as a whole raised questions as to the scope for political art in the 1970s, through the presence of the artist and the absence of the artwork, and in particular this was seen through the dichotomy evident in Beuys’s own contribution. The common ground linking the three artists discussed here – Beuys, Neagu and Vostell – is one in which conflict itself is placed at the forefront of artistic engagement. For all three, conflict was a further mode of communication which in turn served as a confrontation of social and artistic legitimacy, mediated through the concepts of absence and presence. Beuys’s participation in this exhibition was therefore symptomatic of a larger crisis of artistic practice during the 1970s facing all socially and politically aware artists: a crisis of legitimacy itself.