Since the 1990s, there has been a burgeoning interest in the ‘global’ manifestations of conceptual and performance-based practices. Writing for the catalogue of the 1999 exhibition Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–80s at the Queens Museum of Art in New York, Thai art historian and curator Apinan Poshyananda singled out Southeast Asia as a site where conceptual practices took deep-seated roots after the Second World War and offered scope for developing new concepts and manifestations which spoke to the Southeast Asian social, political and cultural contexts: ‘The term conceptualism embraces various forms of art in which the idea of the work is considered more significant than the object itself.’1

Two decades since Global Conceptualism, Poshyananda’s reflections continue to resonate. While no survey of conceptual art in Southeast Asia has been undertaken to date, there is a profound interest in investigating idea-based, performative and intermedia art beyond the chronologies of post-Second World War Euro-American art histories. In this respect, a number of archiving initiatives and exhibitions have shed light on the role of key figures in conceptualism’s early development, primarily across the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore from the 1960s until the 1990s.2 Moreover, these have often reiterated the role of artistic production as the locus of conceptual and performative art-making, thus echoing Poshyananda’s framework of ‘Con Art’ as an effort to foster political critique.3

Yet what frequently remains outside the scope of discussion is the relationship between conceptual practices and discourse-building – in the form of writings and exhibition-making – which often had close ties with established institutions and educational systems. This paper explores the central role of discourse-building and institutionalisation in fostering conceptual, abstract, installation, performance-based and intermedia practices. It examines this via the framework of the Philippine visual art scene of the 1960s and 1970s, which it argues was a particularly fertile ground for early experiments in process, interactivity and participation. From the installation-like ‘environments’ of Roberto Chabet to the community-centered compositions of José Maceda, and the interactive performances of David Medalla, Judy Freya Sibayan and Raymundo Albano, a number of artists working during the 1960s and 1970s sought to navigate the boundaries between so-called ‘experimental’ practices, the cultural politics of the Marcos regime (1965–86), and international discourses around contemporary art and the ‘avant-garde’. Expanding upon curator and art critic David Teh’s notion of ‘currency’ as a negotiation of national, regional and transnational art practices via key terms, this paper investigates the significance of ‘experimental’ art as a term in the Philippines during the 1960s and 1970s.4

The aforementioned five key figures hailed from different backgrounds – Chabet, Albano and Sibayan all produced art alongside prolific careers as independent and institutional curators (and teaching, in the case of Chabet) in public institutions in Manila; Medalla devoted his life to art while traversing the creative circles of Europe and the Philippines; and Maceda was active as a composer, university professor and ethnomusicologist. Seen together, however, they provide valuable insights into the evolution of ‘experimental’ art across artistic practice, discourse-building and institutionalisation. Their works highlight how ‘experimental’ was deployed both as an umbrella term for installation, conceptual and performance art, and as an encapsulation of the discursive tensions and internal struggles among artists working in the Philippines.5

Commencing with an overview of key developments in Philippine art during the 1950s and 1960s, this paper subsequently divides into three sections which examine how ‘experimentalism’ was mobilised in individual works, as well as curatorial discources and critical writings. The first section presents early iterations of the term in relation to the practices of Chabet and Medalla. Examining how this term steered away from conceptual and performance art, minimalism and installation emerging from the USA and Europe in the 1960s, it argues that ‘experimental’ offered scope for artists to advance locally-driven discourses and concepts, and subtle forms of criticism under the authoritarian Marcos regime in the 1970s.

The second section of the paper highlights the simultaneous ways in which ‘experimental’ was mobilised within government-backed institutions, in particular the Cultural Centre of the Philippines. It explores how artists acknowledged and engaged with this co-option, paying particular attention to Albano’s attempts to legitimise a broad range of formal experimentations under the notion of ‘developmental art’, and Sibayan’s critique of the failure of institutional practices to produce a new form of ‘avant-garde’ through her performances and writings.

Finally, this paper also considers the relevance of the term ‘experimental’ for discourse-building, beyond discussions of institutionalisation. The third section examines iterations of ‘experimentalism’ in relation to folk traditions, technology and community. It considers Albano’s writings on installation and Maceda’s participatory musical ‘happenings’ as examples of initiatives which operated at the institutional nexus, yet sought to advance the parameters of the ‘experimental’ through participation, performance and installation beyond the visual arts. Returning in conclusion to ‘experimentalism’ as a form of currency, this paper argues that the mobilisation of this term by individuals sat across and ‘beside’ the frameworks of the national, transnational, and collective imaginations from which many strands of contemporary Philippine art in the 1960s and 1970s took their impetus.6

Artistic and political ecology, 1960s and 1970s

Emerging from a period of decolonial struggles after the Second World War, the art scenes of 1960s Southeast Asia were not marked by a unified style or movement. Rather, the rising presence of internal power struggles, coupled with the dynamics of the Cold War, came to play a formative role in reorienting artistic practices away from the internationalist ideals of the 1950s and towards more nationalistic frameworks. Ahmad Mashadi has noted that in the aftermath of the Bandung Conference of 1955, disillusionment with the seemingly ‘universal’ style of abstraction marked a decisive turn towards aesthetic experimentation and discursive explorations in the 1960s and 1970s.7 Artists distanced themselves from the language of international solidarity, and came to question the systems of art education which bound their creative practices to forms of national identity. In the wake of President Suharto’s New Order regime in Indonesia, this development was exemplified by the activities of Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (the New Art Movement) (1974–9), a constellation of artists from the cities of Bandung and Yogyakarta.8 Their conceptually leaning practices gravitated away from established art systems and rejected the view that art was universal. In the self-published Black December Statement (1974), the group took a critical stance against the lack of social and political consciousness in Indonesian fine arts, and proclaimed a commitment to intermediality, as well as the elimination of the division between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art.9

The initiatives of Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru illustrate a close-knit connection between early conceptual and performance practices, and a desire to expose the structures and contradictions of nations in the wake of post- and neo-colonialism, and in newly established dictatorships.10 In light of such examples, Patrick Flores has argued that the 1960s and 1970s marked a crucial moment in which ‘the international requires, or anticipates, a performative expansion of practice’.11 However, as this paper will argue, this ‘performative expansion’ was activated not only through the visual language of art; it also surfaced in curatorial practice and writing in order to explore new artistic identities in Southeast Asia. In Malaysia, the exhibition Towards a Mystical Reality and its accompanying manifesto, published by artists Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Eisa in 1974, proposed that the roots of Malaysian modern artistic practice lay in the cultural and philosophical traditions of Asia as they came into conversation with international concerns.12 Proposing a distancing from Western influences, the manifesto called for the creation of artistic practice and discourse which went against state-sanctioned art forms and ideological affiliations in the wake of the Cold War.

Preceding the birth of conceptual practices in Indonesia and Malaysia, the Philippine art scene had been already undergoing transformations since the early 1960s, which marked the birth of performative and concept-driven forms of art. As in many other Southeast Asian states, Philippine modern art of the 1950s had been dominated by abstract painting and sculpture. In 1957, the Art Association of the Philippines – an influential body of art critics and curators founded in 1948 – witnessed a charged debate around the dominance of abstraction over figuration in Philippine modern art.13 Culminating in a ‘walkout’ from their annual competition by the conservative factions of the association, abstraction came to be recognised as the most influential form of artistic practice after the Second World War. This development gave impetus to a new wave of formal experimentation in painting and sculpture in the following decades.14

By the early 1960s, an expansion of the parameters of abstract art was further fuelled by the opening of a number of private galleries supporting new forms of practice. These notably included the Philippine Art Gallery, established by Lyd Arguilla, and the Luz Gallery run by Arturo Luz. Both galleries were established as part of the wider economic and urban changes in Manila in which Makati became the new financial district and a benchmark for modern urbanism drawing on the ideas of the artist Fernando Zóbel (1924–84).15 Furthermore, throughout the 1960s and continuing into the 1970s, numerous commercial and artist-run independent spaces such as Arts Laboratory and Shop 6, among others, also came into existence. These provided systems of support and opportunities for artists looking to form networks and exhibit in solo and group exhibitions. For this emerging generation of Philippine artists, abstract expressionism, minimalism, assemblage art and performance from Europe and the US remained a strong influence. An influx of publications, as well as interpersonal exchanges and contacts, allowed them to access the discourses associated with these movements.16 As the decade progressed, a number of artists who had lived or travelled abroad, including David Medalla, Roberto Chabet, Ben Cabrera, Nena Saguil, Arturo Luz, Napoleon Abueva, Constancio Bernardo and Jose Joya, also returned to the Philippines with news of developments in artistic practices and discourses, as well as political positions, which all fed into a nascent ecology of what would later be termed ‘experimental art’.

This period was also marked by a transition from democracy to an authoritarian regime, and finally martial law in 1972 under the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. In the aftermath of Japanese occupation during the Second World War, the Philippines gained independence in 1946. The series of post-war governments which followed continued to maintain close political and cultural ties with the US. In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos of the Nacionalista Party was elected president. Following his re-election in 1969, Marcos initiated a new socio-economic regime. Under the new rule, the Philippines experienced the rapid construction of infrastructure projects, accompanied by intense censorship, restrictions on personal and political freedoms, and human rights violations. As part of Marcos’s vision to foster greater international recognition for the Philippines, the government instigated the building of large new edifices – most famously the Cultural Centre of the Philippines (CCP) in Manila – which was at the heart of significant changes in the arts and culture.17 Constructed with partial support from the US, the CCP was envisioned as an emblem of a cultural politics which sought to present the Philippines as a multimedia ‘mecca’ for international art, dance, music and theatre within Southeast Asia.18 With its inauguration in September 1969, the CCP also launched a visual arts department, the CCP Art Museum. Over the course of the 1970s, this played a formative role in the visual arts through changing exhibitions featuring both international and local contemporary artists, as well as awards, public programmes and publications. As Mashadi noted:

The visual arts initiatives offered an internationalist orientation focusing on high modernism and new experimental forms, including conceptual and performance art which were seen as extensions of an emerging Filipino modernity that seamlessly embraced a dynamic spirit inherent within regional and indigenous cultures.19

Through its diverse programme, the CCP Art Museum wielded a strong influence on a national level by inviting both established and emerging artists to become involved in exhibitions and award schemes. In doing so, it played a formative role in steering discourses around abstract, minimalist, installation-based and conceptual art – all deemed ‘experimental’ media which were officially sanctioned as part of the cultural politics of the institution. However, this seeming openness and commitment to formal experimentation – or, in the words of the CCP Art Museum’s first director, Roberto Chabet, art which showed ‘an articulate command of means to pursue innovative solutions’ and ‘a confident commitment to ideas’20 – was also underpinned by incipient exclusions. The programmes of the CCP expressly rejected art which bore messages of overt political expression or criticism, most notably by social realists. Coming together in the 1970s, the Philippine social realists were a group of artists who drew on international leftist leanings in order to stage overt and satirical political critique against the Marcos regime; they primarily used figurative painting alongside cartoon and poster-making, public enactments and installations.21 Their mode of work often demonstrated strong performative and conceptual elements, yet their political nature ensured they remained outside the scope of the ‘experimental’ art programmes of the CCP.22

Despite the backing afforded to conceptual art by institutions such as the CCP, this paper argues that the emergence of a Philippine ‘experimental’ art should not be dismissed purely as a politically ‘coerced’ form of art and, hence, a counter-example to ‘global conceptualism’ as a fight against dictatorial and canonical formations in Southeast Asia and internationally.23 Rather, it is worthwhile exploring the interconnections between practice, institutionalisation and discourse-building within the framework of individual artists where the notion of ‘experimental’ art came to hold specific importance and took on numerous nuances.

Towards ‘experimental’ practice

In recent attempts to map the histories of ‘experimental’ practices, the works of Roberto Chabet have come to prominence.24 After pursuing a career in architecture, Chabet turned to art-making in the late 1950s, and took part in several group exhibitions in contemporary art galleries across Manila. His first solo exhibition at the Luz Gallery in 1961 marked him as an important emerging figure in the Philippine art scene, working to challenge the conventional parameters of sculptural practice.25 Subsequently, after returning to the Philippines from the US and Britain (where he had travelled on a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation) in 1969, Chabet became employed as the first director of the newly established CCP Art Museum.26 Over the course of this short-lived appointment from 1969–70, he initiated a number of exhibitions and launched a prestigious award for experimental practice, the Thirteen Artists Award, laying the foundations for the CCP’s commitment to experimental and modern art practices in the decades to come.

Fig.1

Roberto Chabet’s Hurdling 1970 in the exhibition Sculptures, Cultural Centre of the Philippines, 1970

© Roberto Chabet Archive, Asia Art Archive

In terms of his own practice, Chabet’s early installations from 1970 to 1975 provide informative insights into key shifts in the Philippines art scene. Influenced by the work of Marcel Duchamp and Fluxus, his work demonstrated an engagement with transnational discourses around conceptual art, performance and assemblage art. On the one hand, his practice aimed to assert the inherent place of these media within Philippine and Southeast Asian art and culture; on the other hand, it also sought to challenge the rigidity of minimalism on a formal level. These principles may be seen in works such as Hurdling 1970 (fig.1), one of Chabet’s early installations in which he deployed readymade materials. Hurdling comprised a series of vertically suspended frames (a reference to athletic hurdles) from which stemmed jagged protrusions made of found scraps of metal. Signalling danger and an impossibility for functional use, the work produced a spatial intervention in the gallery space at the CCP, when it was first shown as part of the 1970 group exhibition Sculptures. Exhibited in this context, Hurdling reflected a new stage in Chabet’s artistic development towards the making of immersive installations, or what he termed ‘environmental works’.27 Approximating Alan Kaprow’s definition in ‘Assemblages, Environments and Happenings’ (1966), Chabet’s use of ‘environments’ to describe such works evoked a fluidity between art and life, and a theatrical encounter which required movement on the part of the viewer in order to experience the work’s interplay on space, perspective, light and mass. This piece, along with a number of subsequent installations, not only drew on architectural forms but also on principles of perspective and illusion from the world of theatre.28 While embracing overt references to international minimalist practices in the 1960s, these works additionally made references to local events such as the post-war reconstruction of Manila, a theme which Chabet and a number of other artists recurrently explored through the use of everyday, readymade and found materials such as scraps of iron, plywood and rubber. Simultaneously, the work tapped into conceptual art practices through its play on language. The use of the word ‘hurdling’ in the title, for example, held a double reference to the ‘hurdles’ of the art world which artists needed to navigate in order to succeed. By further using a form suggestive of a frame – a recurring motif in Chabet’s installations from the early 1970s – the artist alluded to a break with traditional art forms, and all of the hazards that come with it, including a lack of commercial opportunities and discourse, as well as fierce competition.

Through this rich use of metaphors and allusions, Chabet attempted to initiate what artist and curator Ringo Bunoan has described as ‘veiled critiques’ of the art world, by situating himself not only as an observer, but also as a critic.29 The artist elaborated upon this conscious positioning in an interview with critic Cid Reyes in 1973:

Reyes: You have been considered an initiator of a movement variously called ‘Conceptual Art’ or ‘Art as Idea’. What motivated you to explore this field?

Chabet: My works really are more properly the works of an art critic. I mean they are the works in which the concept behind the work of art is the art itself. These days – and especially in a country like ours where there are no art critics – the artist assumes the role of a critic by questioning the nature of art. And I don’t necessarily mean writing about it, the way an art critic would.30

In addition to describing his formal shift away from sculpture, towards performative and discursive practice in the late 1960s, Chabet’s ‘artist-as-critic-pose’31 – a term borrowed here from Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez – allowed the artist to converse across the independent practices and institutional contexts presented here under the rubric of ‘experimental art’. This became the crux of Chabet’s collaborative projects with artists Raymundo Albano and Boy Perez in their work under the pseudonym Liwayway Recapping Co. (also known as the Mayon Vulcanising Co.).

Fig.2

Pages from a manifesto for Liwayway Recapping Co.’s exhibition at Joy Dayrit’s Print Gallery, Manila, May 1970

© Estate of Joy Dayrit

Over the course of its loose existence in the early 1970s, the group staged a limited number of ephemeral exhibitions.32 Similar to Chabet’s solo works such as Hurdling, a notable feature of their practice was the creation of immersive spaces around which audiences could move and experience the play of light and shadow. This experimentation with form and perspective, however, also tapped into the artists’ playful and humorous attitude towards the professionalism of art-making. In a sarcastic and lighthearted self-published manifesto for a group exhibition in May 1970 (fig.2), the artists captured this blurred boundary between professionalism, experimentation and independence which they saw as engaging with a number of aspiring ‘avant-garde’ initiatives in the 1970s:

The Liwayway Recapping Co. held its first exhibition at Joy T. Dayrit’s print, now extinct, and this exhibition lasted only for four hours – six to ten in the evening. For those of you who missed the direct experience of this exhibition, these pictures are for you to look at. No attempt will be made to explain what the pictures are all about. You won’t feel the same sensation we felt when we experienced the exhibition as a whole that evening, you won’t feel what the balloons are all about, and we will feel sorry for you, but nevertheless no attempt will be made to explain what the pictures are all about. Yours truly, the Liwayway Recapping Co.33

The tongue-in-cheek tone of this statement can be read as an invitation to discuss what constituted art, and who could produce its discourses. All the meanwhile, the intertextuality of the Liwayway Recapping Co.’s projects not only served as an artistic statement, but also as a means of producing a discourse around the notion of ‘experimentalism’.

On the one hand, the Liwayway Recapping Co.’s understanding of ‘experimental’ was grounded in the use of impromptu actions, alongside everyday forms and objects which spoke to the material reality of the Philippines. Their activities referenced the ‘happenings’, the performances or events staged in everyday settings as works of art in New York in the 1950s, as well as the anti-institutional, interdisciplinary and collaborative spirit of the revolutionary avant-garde organisation Situationist International in Europe. On the other hand, ‘experimental’ also described a resistance to being seen as mimicking international avant-gardes. Chabet commented to Cid Reyes on the notion of ‘avant-garde’ in relation to the Philippines: ‘What is considered “avant-garde” in the Philippines may not be “avant-garde” in another country. Let’s just call it “experimental” art.’34

In light of this distinction, the role of humour and parody was particularly important in conveying this alternative, locally rooted expression of ‘experimentalism’ which surfaced not only in works by the Liwayway Recapping Co., but also in a number of other conceptual and performative practices of the time.

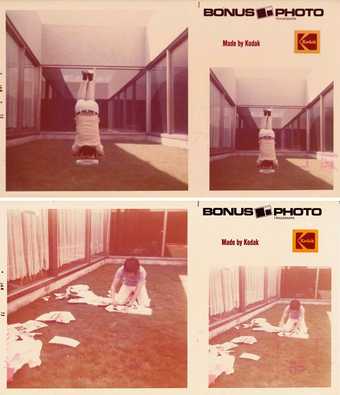

Fig.3

Yolanda Laudico

Roberto Chabet performing Tearing into Pieces 1973, Cultural Center of the Philippines, Manila

© Yolanda Perez Johnson

In 1973, Chabet staged a private performance at the CCP in which he tore apart the recently published book Contemporary Philippine Art (1972) by the art critic Manuel D. Duldulao.35 Published independently, Duldulao’s book gave an overview of developments in contemporary art, including Chabet’s paintings as examples of key developments in Philippine contemporary art.36 Chabet’s performative destruction, known as Tearing into Pieces, was captured in a photographic series taken by fellow artist Yolanda Laudico (presently Yolanda Perez-Johnson). The photographs depicted Chabet playfully destroying the book before posing on top of, and practicing yoga alongside, the torn-out pages (fig.3).

As this private performance represents a rare example of explicitly emotional enactment by Chabet, it is tempting to interpret it as symbolic act of subversion, or resistance, against the efforts of canonisation found in Duldulao’s book. Yet it was also staged as a condemnation towards a perceived lingering drive in Philippine art criticism to epitomise painting and sculpture as examples of avant-garde practice, without recognition of Chabet’s later efforts to experiment with forms and materials. This reading finds support in the performance’s aftermath – Chabet chose to display the torn-out ‘remains’ of the book in a trash can as an untitled sculptural mound in the 1973 group show at the CCP, An Exhibition of Objects, curated by Raymundo Albano.

Given the final exhibition context of the work, it is impossible to divorce Tearing into Pieces from the institutional and political framework within which it was produced. Critically assessing Bunoan’s description of Chabet’s works as ‘veiled critiques’, it is crucial to remember that Tearing into Pieces was to be shown ‘as art’ within the very institution which also exhibited numerous works mentioned in Duldulao’s book as examples of important contemporary art practice. Furthermore, Chabet and Albano were not only practising artists immersed in the experimental art scene; they were also cultural professionals working very much ‘within’ the system. As mentioned previously, Chabet had been appointed the first director of the CCP Art Museum, with Albano filling in the role of deputy director. After Chabet’s resignation in 1970, Albano first took over the role as interim director, and was subsequently appointed as director, holding this position until his death in 1985. Thus, in light of both Chabet’s independent practice and his collaborations with Albano, there emerges an understanding of ‘experimentalism’ as a fusion of humour and parody in order to stage light-hearted, confrontational contexts. This runs in contrast to the expressions of activism seen in the works of the social realists in the Philippines and, later, in the conceptual art of the Indonesian New Art Movement. Such actions, while often seemingly benign and even mundane in their form, were however very important to the individual practices of these two artist-curators, for it allowed them to traverse the institutional-independent nexus – a point which this paper will return to in the next section. Capitalising upon the notion of ‘experimental’ aligned them with an emerging discourse around conceptual art, described by Albano as aiming to lead viewers to question their realities and presuppositions.37 Thus an understanding of ‘experimental’ art emerges from these examples not only as an expression of ‘pure’ concept, but as also as a politico-poetic gesture.

This understanding may be traced in the practices of expatriate artist David Medalla, whose work abroad came to play an important role in the Philippines, albeit one sometimes under-explored from the position of a national art history.38 Having departed for Europe in 1960, news of Medalla’s engagements in London’s kinetic art scene at Signals, London (1964–6) and with the performance group Exploding Galaxy (1968–70) continually reached the Philippines.39 Over the course of the 1960s, Medalla’s traversal of media and networks abroad became synonymous with the notion of ‘experimentalism’, with Chabet describing Medalla in 1973 as an artist who ‘never stops experimenting’.40

On the one hand, Medalla’s formal transition from abstract painting and sculpture to a deeply performative mode of art-making in the 1960s rendered his practice an independent navigation of different artistic and cultural traditions which transcended nationalism. On the other hand, his increasing engagement with various leftist political causes in the 1970s, ranging from the war in Vietnam to decolonisation, the rise of dictatorial governments in Southeast Asia and workers’ rights in Britain, also led to an understanding of his work as an experimentation across the boundaries of the political and poetic. As later noted by Medalla in an interview with Pakistan-born artist Rasheed Araeen in London in 1977, ‘the so-called marginal art forms – not the marginal artists – may express a deeper reality better than the major accepted art forms’.41

This positioning across the political, poetic and aesthetic was important for the Philippine art world – although Medalla was no longer present in person, his work symbolically straddled the perceived divide between conceptual and political art. This ability to independently navigate existing demarcations came to the forefront when Medalla returned to the Philippines in 1969. Despite working in media championed by the CCP, Medalla harboured a scepticism of art being embedded within institutional structures, arguing that museums were spaces in which performative art lost its spirit and efficacy.42 Perceiving many of the featured works in the CCP programme to have abandoned their political and social agency, Medalla staged a protest at the opening of the CCP in which he and his peers Mars Galang and Jun Lansang arrived uninvited to the opening reception and unfurled hand-made posters from the balcony of the central foyer. Captured in a much-circulated photograph showing Medalla holding a placard reading ‘Abas la Mystification! Down with the Philistines!’, this agitprop gesture objected to the building of state-backed cultural institutions in an increasingly authoritarian political system.

While the political cause behind this protest served as a precursor to several of his most important participatory performances and installations such as Down with the Slave Trade 1971 and The People’s Participation Pavilion 1972, created with John Dugger for Documenta 5, Medalla refused to have his art limited to activism.43 Through works such as A Stitch in Time 1972, a participatory installation in which viewers were invited to stitch small objects and designs onto a suspended stretch of cloth, he espoused an understanding of ‘experimental’ art as rooted in the making of social contexts. In the words of critic and curator Guy Brett, these contexts served as ‘a microcosm of the phenomenon of artistic movements themselves, which, at their most creative and challenging moments inspire people to surpass themselves, a phenomenon that is greater than any single individual talent’.44 In contrast to the importance placed on materiality and form in the ‘environments’ of Chabet and the Liwayway Recapping Co., Medalla’s art insisted on the centrality of interaction and interlocution. Thus, the final material ‘product’ was only of secondary value to the work’s discursive possibilities. A Stitch in Time did not require an institutional context to be shown, and could be readily staged in a variety of settings, where it served as a medium for interaction and conversation on themes ranging from everyday events to the artworld and politics.45

As his practice could be strictly ascribed neither to the political nor conceptual realm, Medalla’s art came to represent a ‘gesture’ towards the increasingly intertwined connection between political discourses, institutional outreach and experimental art in the Philippines.46 This iteration of ‘experimental’ art as politico-poetic action not only preceded later practices by social realists in the Philippines, but also reflected early transnational connections to politically versed conceptual and kinetic practices by artists from Latin America, most notably Lygia Clark, Sérgio Camargo, Hélio Oiticica and Jésus-Rafael Soto, with whom Medalla had contact in London.47 Despite the fact that he sought to distance himself from the Philippines after this protest and travelled back to Europe, not to return to the Philippines again until 1986 after the fall of the Marcos regime, his works sparked an investigation of the nexus between institutionalisation and experimental practice which later surfaced in the practices of a number of other artists who remained in the country.

Negotiating the institutional nexus

As a ‘hyphenated artist-curator’, Raymundo Albano engaged with the question of how it was possible to theorise about developments in contemporary art while allowing for the fluid relationship between institutionalisation and experimentalism to continue existing.48 Having served as Chabet’s assistant director of the CCP Art Museum in its first year from 1969–70, Albano took over its directorship after Chabet’s resignation. Over the course of his term, he remained active as an artist, poet, poster-maker, folk theatre set designer and writer, alongside playing a leading role in establishing influential publications such as the Philippine Arts Supplement and Marks, which fostered critical writings on ‘experimental’ art in the Philippines.49

According to Flores, one of the most pressing questions which Albano faced was how experimental practices could be legitimised within the context of government-backed institutions such as the CCP which upheld censorship against art that was politically critical.50 Grappling with this question at a time when performative and conceptual practices were internationally associated with counter-culture movements, Albano explored how the language of modern art could be mobilised in order to justify showing a wide-range of experimental practices within the CCP, meanwhile retaining a degree of autonomy of expression.51

In 1978, Albano coined the term ‘developmental art’ to describe the heterogenous practices he wished to support within the CCP.52 On the one hand, this notion echoed the government’s rhetoric around the drive to ‘develop’ the Philippines’s economy and infrastructure. On the other hand, it also referenced the making of fast, ephemeral and process-based projects which were characterised by the use of readymade and industrial materials, as was the case in many ‘experimental’ art practices of the 1970s.53 By interlacing several nuances into the term, the notion of ‘developmental art’ appeased government strictures, while accommodating practices that crossed different media and had performative elements with the potential for underlying meanings.

In light of this, Albano’s writings emerged from a position which sought to understand the mechanisms through which ‘experimental’ practices became embroiled with processes of institutionalisation. However, by virtue of his institutional role, they also turned a blind eye to the social and political injustices taking place under the Marcos regime, or refused to engage with histories of cultural and economic imperialism through which Philippine (art) history had come into formation. This understanding of ‘experimental’ art thus reflected a positive and at times also complacent affirmation of Philippine modernity seeking to position itself within an international framework. As noted by the art critic Marian Pastor Roces:

The belief system that sustained the frenetic art-making was based on a certain Philippine art version of, believe it or not, nationalism. There was this hyper-consciousness about local art finally, ecstatically moving in synchrony with New York, San Francisco, Tokyo, and possibly even pushing ‘ahead’ more progressively than in Paris, London, Rome.54

Despite Albano’s efforts to generate a theoretical framework around the notion of ‘developmental art’, the term did not take on deep roots in artists’ own terminology to describe their works.55 Instead, a desire to understand the power dynamics which governed the ‘experimental’ art scene in the Philippines became the subject of works by other artists, most notably Judy Freya Sibayan.

Having studied under Chabet at the University of the Philippines Diliman between 1972 and 1975, Sibayan’s entry into the world of contemporary art had been highly influenced by Chabet’s engagement with writings on contemporary and experimental practices from the US in this period. Writing in 1988 for the catalogue of the Thirteen Artists Award while she was director of the Contemporary Art Museum of the Philippines, Sibayan described her experience of studying ‘experimental’ art during the 1970s under Chabet:

We [Sibayan and her peers] didn’t perceive ourselves as belonging to specific ‘species’ (painter, printmaker, sculptor, photographer, etc.). We did what was demanded by the investigation [of art] – whatever formalized a concept, be it the manipulation of space, light, architecture, human bodies or human behaviour ... art made with the aim of studying and researching art further. We engaged in performance art, for instance, in order to investigate the inevitable ‘loss of species’ in art or the blurring of borders that separated art forms. With these experiments, we tried to extend the idea that to make art was to perform a task. We tried to affirm that what was essential in artmaking was not the object created but the process of creating art and the good this process did to ourselves.56

Over the course of her degree, Sibayan began developing ephemeral actions with fellow artist Huge Bartolome which formed the basis for her later engagement with parody and institutional critique.57 These early ‘classroom performances’ were often initiated by Chabet’s instructions and assignments for his students and took the everyday functions of the university and its hierarchies as the starting point for interrogating the power dynamics which determined what could be deemed art.58 As an example of her performances from the time, the artist has recalled staging a work in which she stood on one end of a path with Bartolome on the other end; each held a balloon which they requested be given by passers-by to the person standing at the other end.59 This exchange was performed for an hour with only one audience member, Sibayan’s professor, the renowned Philippine abstract painter Constancio Bernardo, who viewed the performance from his office on the fourth floor of the College of Fine Arts.

Fig.4

Judy Freya Sibayan’s Lemon Cake, performed in the car park of Sining Kamalig shopping complex, Manila, 1974

© Judy Freya Sibayan

As a young student beginning to engage with the question of what structures – and who – had the power to assign actions and objects the status of ‘art’, Sibayan argued that such performances constituted part of a wider investigation into how to ‘have the agency to do art that would be validated and legitimised as art.’60 In later works, Sibayan extended her exploration of power dynamics beyond the university and began using performance and conceptual art as a means to expose power structures within the Philippine art world. In Lemon Cake 1974 (fig.4) – a work which Sibayan acknowledges as her first formal ‘happening’ – the artist staged an impromptu performance in the car park of the shopping complex Sining Kamalig. Established by Chabet, inside the complex was Shop 6, one of Manila’s earliest alternative spaces, where a group of artists working in the media of installation, conceptual and performance art congregated. Sibayan’s Lemon Cake was enacted during the launch of a group exhibition at Shop 6, in which her works were not featured. In response to this exclusion, Sibayan and three other students stationed their Renault in the car park and placed a lemon cake on the hood to mark the artist’s birthday. As visitors passed by on the way to the exhibition opening and inquired what the artists were doing, they responded solely with the words ‘lemon cake’ and proceeded to eat the cake until it was finished.

Despite not having been part of the official exhibition, a photograph and description of this adjunct performance were included a review titled ‘101 Artists: Incidents at Sining Kamalig’ published by Albano in the art magazine Marks:

A yellow car docked at the middle of the parking lot, filled with people eating and drinking, not minding anyone. Afterwards, they opened all the doors of the car, set half a pie, two half-empty Magnolia Chocolait bottles, and a metronome on top of the car’s front.61

Described by Albano as an experimental work with an emphasis on confusing gestures and playful behaviours (as echoed in the aforementioned works by the Liwayway Recapping Co.), the review ignored the protest nature of the work. In contrast, Lemon Cake represented an early attempt by Sibayan to articulate the dynamics of insider-outsider status in relation to artists’ networks and the politics of independent spaces, a subject which she later took up during the 1990s in a broader engagement with institutional critique.62 The performance had been conceived first and foremost as an intervention ‘performed in jest in a place that was not designated as a space for art’.63 The fact that it had been retrospectively re-envisioned as a performance artwork by none other than the director of the CCP Art Museum fuelled Sibayan’s interest in interrogating the junction between institutional structures and art, but also underscored the centrality – and inescapability – of institutions in discourse-building during the Marcos era.

Fig.5

Audience at Sound Bags and Three Kings, performed by Judy Freya Sibayan, Raymundo Albano and Huge Bartolome, Cultural Centre of the Philippines, 6 January 1978

Soon after the performance, Sibayan began to engage more directly with Marcel Duchamp’s critique that the art space as context, rather than the object, ascribes artefacts the status of ‘art’.64 Similar to the creation of Chabet’s Tearing into Pieces in the courtyard of the CCP, her practice set out to challenge institutions as building blocks for experimental practice. At the same time, she engaged with the question of how artists in the Philippines, both knowingly and sometimes unwittingly, struggled to navigate and negotiate the boundaries between institutional control, censorship, experimentalism and independence. Examples of works which she produced as part of this investigation included performances such as Sound Bags and Three Kings, performed in collaboration with Albano and Bartolome on 6 January 1978 in the End Room of the CCP’s Main Gallery (fig.5). The artists sat among the audience and took turns bringing out objects from a paper bag, such as crumpled paper and a comb, with which they made varied sounds and amplified these using a microphone – ‘gifting the audience with sounds’.65 Through this action, Sibayan and her collaborators sought to explore the barriers of what could qualify as art within the context of the institution, while speaking from a position within the institution.

It is important to note that alongside such works, Sibayan held numerous institutional roles and affiliations after the completion of her undergraduate studies, first as Curatorial Assistant at the CCP (1976–7), then as an exhibiting artist (1974–81), and finally as Museum Director of the CCP (1987–9), leading her to describe herself as a ‘de-centered’ subject.66 Her personal journey as both insider and outsider became an increasingly present theme in her work, and ultimately morphed into the main subject of her practice. In the 1990s, she returned to a performative mode of art-making in order to reflect upon how the value of ‘art’ was bestowed. With the launch of Scapular Gallery Nomad (started in May 1994 and resumed in 1997), Sibayan sought to expand beyond Duchamp’s notion that the museum context ‘produces’ art. She developed a conceptual work in which she took on a role as the vehicle of a gallery, performing wearing a self-made scapular – a Christian garment made to hang over the shoulders – which served as a ‘gallery’ in which art objects by other artists could be ‘exhibited’. By taking on the role of a mobile ‘gallery’ in which she embodied all institutional roles, Sibayan examined how ‘anyone who contributes to belief in the value of an object, a performance etc. as having value as art, actually produces art’.67 Echoing earlier positions which had been tentatively voiced by the Liwayway Recapping Co., and more overtly expressed by Medalla, Scapular Gallery Nomad signalled the shortcomings of government-backed institutions – particularly the CCP – in fostering a truly avant-garde practice in the Philippines. Taking this critique one step further through art criticism and autobiographical writing, Sibayan retrospectively historicised her practice and articulated her position as an artist striving to work, quoting Linda Hutcheon’s critique of postmodernism in which she describes herself as ‘inside yet outside, complicitous yet critical’.68

She has since argued that the very institutionalisation of ‘experimental’ works by the CCP in the 1960s and 1970s led to the demise of the avant-garde as a result of institutional demands and the cultural politics of the Marcos regime. Sibayan located herself – along with other figures such as Chabet and Albano – as part of an interwoven system of discourses in which the notion of ‘experimental’ practices of the 1960s and 1970s had sought to exist both within, and beyond, the institutional context.69 In doing so, she voiced the concern that the institution had failed to produce a radical new practice which reflected the Philippine identity in the wake of independence, modernisation and postcolonialism. Sibayan outlined this position:

As a process of de-centering, this practice was a response to the failure of the avant-garde with the institutionalization of this failure becoming the condition of another practice, that of Institutional Critique. A subject position locating the artist ‘off-center’ of the art institution, Institutional Critique is a praxis that problematizes and changes this institution but does not affirm, expand or reinforce the artist’s relationship to it. To have left the center/Center was the only tenable response to a situation I found deeply problematic as an artist whose trajectory is to make critical art, that is, art that problematizes the making of art.70

Sibayan’s retrospective writings about her own practice reflect a frustration with the formal production of art since the 1970s. Yet, they also signal the need to recognise that the support granted to experimental practices generated possibilities for developing new forms of discourse. These were not limited to the navigation of ‘veiled critiques’ seen in the aforementioned works of Chabet and Albano, but also explored new discursive and formal productions around the junction of ‘experimentalism’, tradition and participation.

New discursive productions

One important discursive production which steered away from ‘experimental’ art and institutionalisation can be found in Albano’s writings exploring the relationship of installation-making and performativity to local and regional systems of thought.71 In an essay titled ‘Installation: A Case for Hanging’ (1981), he divorced the notion of ‘experimental’ practice from institutional associations as previously developed in his writings on ‘developmental art’. Instead, he considered the performative display of installations through hanging, leaning and spreading, akin to ‘collaborative installations in nature’.72 Spearheading a discussion around the relationships between contemporary art, ecology and community, Albano looked to a number of practices created outside Manila’s conceptual art circles in which the notion of ‘experimental’ also evoked discussions around folk traditions and community practices as contestations of the Western definitions of installation and performance art:

It may be that our innate sense of space is not a static perception of flatness but an experience of mobility, performance, body, participation, physical relation at its most cohesive form. Thus installation is akin to fiestas and folk rituals from all our ethnic groups.73

Whereas previous discussions of ‘experimental’ art at the nexus of institutional discourses had heralded the role of Euro-American discourses, Albano’s writings on installation represented a significant shift in discourse; they advocated a distancing from Euro-American notions of the ‘avant-garde’ in favour of traditional and ecological influences which emphasised the regional roots of intermedia practices in the Philippines. While Albano did not produce these discourses with the intent of divorcing them from his institutional role – a core part of the CCP’s programme was also geared towards presenting traditional forms of music and dance – he aimed to provide the scope for an expanded discussion around what constituted ‘experimental’ across contemporary and traditional forms in the visual arts, music and theatre.

One such prominent iteration of an ‘experimental’ art which engaged with indigeneity in light of transnational and intermedia discourses can be found in the writings of experimental composer and ethnomusicologist José Maceda. Honoured in the Philippines with the title of ‘National Artist for Music’ in 1997, Maceda was trained as a pianist, ethnomusicologist and composer, and came to be known during the 1960s and 1970s for his eclectic compositions. Taking up a professorship at the University of the Philippines in 1952, he continued to carry out research on traditional music by roughly eighty-seven ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines until his retirement in 1990.

Over the course of his career, Maceda engaged extensively with how experimental practices in the arts – particularly performance and music – could serve to foster community solidarity, an interest in history and appreciation of traditional cultural practices within the Philippines. With no interest in generating political critique via his writings, he was more concerned with the structures through which contemporary Philippine society fostered a sense of community and cultural continuity after centuries of Spanish and American colonisation. Similar to Albano’s texts on installation, Maceda’s writings and compositions highlighted his thinking about contemporary art, tradition and society in a new configuration which did not derive exclusively from the Euro-American discourses of avant-garde art. Throughout the 1970s, he published articles around the themes of modernity, technology, tradition and community formation in postcolonial Philippine society, the relevance of which transcended musicology and came to have an influence on contemporary art by questioning how traditional and mass participatory experiences could engage the modern national Philippine consciousness.74

In a 1978 essay titled ‘A Primitive and a Modern Technology in Music’, Maceda cautioned against the over-use of digital technologies in society, particularly in rural areas of Southeast Asia where the ownership of digital technologies served as symbols of affluence which did not reflect real levels of development.75 As a proponent of traditional forms of music, he also advocated for a return to the experience of music as a social and communal event, rather than an embrace of digitally transmitted popular culture from the West, noting that ‘a musical technique foreign to a native culture sometimes tends to adulterate and weaken musical practice’.76 However, recognising the inescapability of digital technologies, Maceda argued in favour of using digital technologies in innovative ways and took a particular interest in technologies used for recording and playing music, which he saw as a means to spread information about traditional practices to the maximum number of people through mass transmissions and participatory events in towns and cities.

Fig.6

José Maceda’s performance of Cassettes 100 in the lobby of the Cutural Centre of the Philippines, Manila, 1971

Fig.7

José Maceda’s performance of Udlot-Udlot, with choreography and special programming by Roberto Chabet, at the University of the Philippines Diliman, Manila, 1975

While writing from an ethnomusicological perspective, Maceda’s ideas around transmission and mass participation had a strong resonance with certain discourses around public and participatory art. They were particularly aligned with Albano’s proposition of ‘experimental’ art as fostering a heightened awareness of realities and presuppositions, as seen in the Liwayway Recapping Co.’s immersive ‘environments’, and with Medalla’s advocation that art’s primary function was to produce shared encounters and social contexts. Such frameworks lent Maceda’s scholarship and experimental compositions a receptive audience within the cultural circuits of Manila.

As noted by the curator Dayang Yraola, while Maceda was a contemporary of a number of visual artists who experimented with performativity during the 1960s, he did not have many connections to the visual arts scene.77 Nevertheless, he collaborated with visual artists on two occasions in order to realise the large-scale, participatory performances, Cassettes 100 1971 (fig.6) and Udlot-Udlot 1975 (fig.7). Both works echoed the principles of participation, community formation and disseminating tradition outlined in Maceda’s writings and have remained highly relevant for the history of ‘experimental’ performance and conceptual art in the Philippines to this day. Cassettes 100 was staged at the CCP and consisted of sound clips of indigenous music previous recorded during Maceda’s fieldwork expeditions. The clips were played simultaneously from one hundred tape recorders held up by one hundred participants who moved around the space in a choreographed pattern. The work was devised with the assistance of visual artists Jose E. Joya Jr and Ofelia L. Gelvezon-Tequi for the design and projections; and the theatre light designer Teodoro Hilado for lights and effects. The performance was documented by the official photographer of the CCP, Nathaniel Gutiérrez, through whose visual records the memory of Cassettes 100 has survived not only as an experimental composition, but also as a pioneering immersive public ‘happening’ in the Philippines. In a similar spirit of collective enactment, Udlot-Udlot premiered at the University of the Philippines in 1975; in it, students simultaneously played instruments including bamboo flutes, stamping tubes and stick beaters. Their collective organisation and spatial movement was choreographed by Chabet, thus developing a work which once again saw the meeting of experimental music, participatory art and theatre.

While Maceda’s writings on indigenous music were often aligned with the rhetoric of cultural preservation and dissemination espoused by the Marcos regime, he avoided introducing discussions of coercion or resistance into his works. Rather than dismissing his institutional works as ‘failures’ to produce avant-garde actions, as argued by Pastor Roces and Sibayan, Cassettes 100 and Udlot-Udlot may also be seen as acts of sonic ‘epistemic disobedience’. The academic and author meLê Yamomo describes how they offered both a new and unfamiliar form and aesthetic, and at the same time operated within the permitted strictures of institutions and politics.78 Maceda’s writings and collaborative performances not only saw the development of a new form of practice in which large social and cultural processes where activated, but also signalled the central importance of considering the multivalent way in which ‘experimentalism’ went beyond institutional frameworks. In doing so, they tapped into discussions around performative art, community, transmission, spirituality and tradition which went beyond regional discussions on conceptual art in the cases of Indonesia and Malaysia. Maceda’s works and discourse also resonated transnationally with the Tropicália art movement in Brazil from the 1960s until the 1990s where experiments with music played a key role, and in the works of Fluxus in Europe during the 1960s and 1970s, when figures such as Nam June Paik became concerned with the role of mass digital transmission in fostering social consciousness.

Conclusion

This paper commenced with the view that the 1960s and 1970s in Southeast Asia have often been seen as periods of political transformation which fuelled changes in art and cultural expression. In light of this context, the birth of ‘experimental’ practices in the Philippines demonstrates a complex relationship in which several key artists developed ways of working with conceptual, performance and installation art across the nexus of institutional and independent practices. In the cases of Chabet and Albano, the two artist-curators maintained close affiliations to government-sanctioned institutions. Their conceptual projects often sought to navigate these ties, looking for formal and discursive ways in which to experiment with forms and ideas while remaining within the accepted language of a national art history. For others, such as Medalla, a positioning abroad enabled a more overt criticism of the co-option of ‘experimental’ practices within a national rhetoric. Developing numerous participatory performances which had both political and poetic elements, Medalla’s practice remained a powerful example of alternative practices beyond the conceptual-political divide in the Philippines. In the works of Judy Freya Sibayan, conceptual and performance art remained deeply rooted in a self-reflective practice which, over time, took on the nature of institutional critique. Here, Sibayan’s writings alongside her artistic practice remained an important element within which the nature of ‘experimental’ art was continually being shaped and revisited through the 1970s. Finally, looking beyond discussions of institutionalisation in relation to the visual arts, the mass participatory performances, or ‘happenings’, composed by José Maceda in collaboration with visual artists offer a reading of early performative practices as modes of mass participation in the collective making of a new hybrid system of sound which fused the traditional and modern, thus forging new conceptions of art and society in post-independence Philippines.

Returning to the core proposition of this paper, ‘experimental’ art was born in the Philippines from a place of continual interlocution between individual practices and politics, both individual and state. While the role of institutions has recently been the subject of substantial inquiry, this paper has highlighted the centrality of individual discourse-building for all five of the artists discussed. In the framework of their practices, the term ‘experimental’ was embraced as a form of ‘currency’ not only to attest to, but also to investigate the roots of their idea-based, performative and intermedia practices ‘beside’ national discourses. Emerging from their numerous writings – ranging from reviews, to interviews, criticisms and autobiographies – are various concepts and terms. These include ‘environment’, ‘developmental art’ and ‘installation’, among others, which convey the nuanced ways in which the nascent national lexicon of conceptual terminology in the 1960s and 1970s continually sought also to position itself ‘beside’ regional and transnational discourses on conceptual and performance art.