‘Unconcealment’ is the English translation of Entborgenheit, a term used by Martin Heidegger. He wrote about art as a form of disclosing, of the artist’s ability to come closer to meanings buried underneath the words appropriated by mythology, religions, empires, science and politics. He wrote about art as a means of ‘enabling what is to be’.1

‘Unconcealment’ can be applied on two different levels to Sophie Richard’s research on conceptual art of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Firstly, it refers to the way in which conceptualism encouraged the analysis of structures and meanings. Conceptual artists took the formal language of documents and images, and turned them in upon themselves, in what I described at the time as ‘self-referential ideas’.2 Secondly, Richard has disclosed the network behind conceptual art during the first decade of the movement. The business of conceptual art, or more precisely the accrual of value, is discussed as one of the layers of meaning buried within the work.

Richard’s Ph.D Thesis International Network of Conceptual Artists: Dealer Galleries, Temporary Exhibitions and Museum Collections (Europe 1967–1977), was presented at Norwich School of Art and Design, an Associate College of Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, in September 2006.3 Sadly, Richard died seven weeks after giving birth to her daughter Lucie, in November 2007, before she had time to prepare her thesis for publication. For me, her death was a personal and professional tragedy. I was her supervisor for the four years of her research, and as a participant in some of the events of the conceptual network, I had handed over my knowledge of this period to her. This is how I came to edit her thesis and prepare it for publication.

Although Richard’s first language was Luxembourgish, she worked with me in English on this thesis.4 She also spoke French, German and Flemish/Dutch. This enabled her to undertake documentary research in museums and archives across Europe. Her data centred on the triangle between the Rhineland cities of Düsseldorf and Cologne, Amsterdam, Brussels and Ghent. Ten of the cities prominent in early exhibitions of conceptual art are in this triangle. Cities rather than countries were key to the development of the conceptual network in the first decade.

The methodology that I handed on to Richard was to work initially, and at length, on primary documents of the period, especially art magazines, taking as much notice of the adverts as the editorials. She consulted my archives in Norwich regularly. She received a research grant from the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds and also worked at the Tate Archive, the Casino in Luxembourgand the Anton and Annick Herbert archive in Ghent. A grant from the Goethe Institute enabled her to consult archives in Germany, including that of Konrad Fischer, the key dealer of conceptual art. She also sought out existing recorded interviews with the leading figures. She defined the groups of artists, dealers and exhibitions for her study so that she could begin the construction of the databases, which are published in the appendices of her book Unconcealed: The International Network of Conceptual Artists 1967–1977: Dealers, Exhibitions and Public Collections, published in 2009. Her data concentrates on public collections and those private collections that have been accessioned in recent years by museums. She chose not to collect data on sales to other private collections during this period. The data therefore focuses on the relationship between the artists, dealers and public collections. She was unable for financial reasons to continue her research in the US.

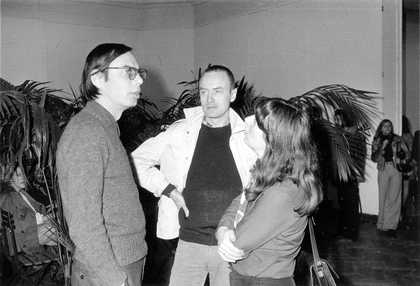

Fig.1

Jacques Charlier

Konrad Fischer, Benjamin Buchloh and Anny de Decker at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1975

Photograph © Jacques Charlier, courtesy Galerie Nadja Vilenne, Liège

Half of the artists in Richard’s databases are from the US and half from Europe. Conceptual art was the first post-1945 art movement to treat American and European artists equally. We discussed the extent to which recent US books on conceptual art had altered this balance. Richard was at the conference for the Tate exhibition Open Systems in 2005 when I questioned Alexander Alberro about the omission of Seth Siegelaub’s July/August 1970 issue of Studio International from his 2003 book Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity.5 Richard took up this argument on subsequent occasions and in the introduction and conclusion of her book. She grasped the bias in perspectives constructed twenty or thirty years after the events in recently published and academic histories. Richard was then equipped to interview the key figures of the movement. She transcribed her own interviews, remembering W.H. Auden’s idea that you understand more by writing out texts rather than by reading or listening.

Richard devised the databases at an early stage of her research although she continued to add to them throughout. She requested access to accession files and information on purchases from museums and information in exhibition archives, persistently overcoming the reluctance of museums to release this information. As a result of EU Freedom of Information Legislation, The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, and Tate, London, allowed her access to their accession files and the prices they paid for works. Other European museums gave information regarding the dealers from whom a work was purchased. The Stedelijk and Tate prices enable readers to estimate the prices being paid for other works. Richard’s databases can be compared with the prices quoted by Willi and Linde Bongard’s Kunstkompass chart of the top one hundred contemporary artists, some of which are reprinted in the appendices of her book.6

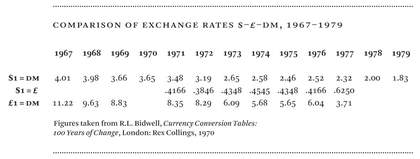

Prices have been kept in their original currencies in the databases because of the difficulty of establishing actual exchange rates on sales that often took public museums twelve or more months to complete in a period of economic turbulence. I have prepared an additional chart of the exchange rate fluctuations between the pound, the dollar and the deutschmark during the period 1967–7. Sterling floated between 1969 and 1971, bringing to an end the Bretton Woods System of pegged exchange rates. Currencies further fluctuated in the early 1970s with inflation. The instability increased with the escalation of the Vietnam War and the oil crisis resulting from OPEC price increases after two Arab-Israeli wars, terrorism and the riots of alienated youth. The pound was decimalised in 1969: 240 pence in a pound meant that each new penny was worth 2.4 old pence and was considered to have caused inflation and undermined the pound. In the late 1970s, an Exchange Rate Mechanism – the ERM – was introduced inEurope (table 1).7

Table 1

The £ floated between 1969 and 1971 bringing to an end the Bretton Woods System of pegged exchange rates. Currencies further fluctuated in the early 1970s with runaway inflation. The instability was increased because of financial pressure of the escalation of the Vietnam War and oil crisis resulting from steep OPEC price increases in the wake of two Arab Israeli wars. The

pound was decimalised in 1969. With 240 old pence to the pound, each new penny was worth 2.4 old pence. This was further considered to have caused inflation and undermined the value of the pound. In the late 1970s an Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) was introduced in Europe.

Figures from R.L. Bidwell, Currency Conversion Tables: 100 Years of Change

Richard chose not to illustrate her thesis, but I started to develop with her the idea of an exhibition to mark the eventual publication of the thesis. This exhibition was to bring together three artists whose work addressed the internal contradictions of radical conceptual art: André Cadere, who colonised other people’s exhibitions with his ‘round bar of wood’; Ian Wilson, whose Conversations were a psychoanalysis of his audience; and Jacques Charlier. For Richard’s book, I worked with Charlier to select forty of his 600-plus Vernissage des Expositions photographs from 1974–5, made for his exhibition at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, alongside On Kawara. Charlier’s catalogue for his exhibition was of the photographs taken at its vernissage. It is an extraordinary photographic record of the heyday of the ‘network of conceptual art’.

My introduction to Richard’s book is based on an analysis of the databases that she created for her thesis. The use of databases is appropriate to a study of conceptualism, because the revelation of information through data was one of the ways in which conceptualism defined itself. Future users of Richard’s databases will be able to consider the extent to which economic factors have influenced the direction of recent art that is usually viewed as aesthetically independent.

Conceptual art in the first decade was a true avant-garde. This period was marked by a corresponding emergence of a new generation of young dealers who developed innovative means of distribution, and they frequently worked as curators of exhibitions in public galleries and museums. An analysis of Richard’s data suggests that there was a correlation between these exhibitions curated by dealers and the subsequent purchase of the artists’ work by museums. The questions raised by Richard’s data are for the public sector to analyse. Private-sector dealers of radical contemporary art are there to sell their artists’ work, and there is no conflict in that. This was less of an ethical dilemma then, when the environment was less commercial.

The databases concentrate on fourteen dealer galleries. My introduction discusses the most dramatic story, that of Konrad Fischer. He started his career as an artist and then opened a space in Düsseldorf, selling to museums in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. In the mid to late 1960s, young Germans were on a mission to work with US artists. Germany was the front line of the Cold War and NATO was its protection. In an interview with Jorge Jappe, Fischer said: ‘When I was an artist everything was so far away; Warhol, Lichtenstein and all those were great unattainable men. But when you know them, you can have a beer with them and get rid of your inferiority complex. I insist that the artist has to be there when I show his work, … Palermo and Richter … two of the German artists who have exhibited with me, have now been to New York, and they felt at home there because they had already met artists like Andre and LeWitt over here’.8

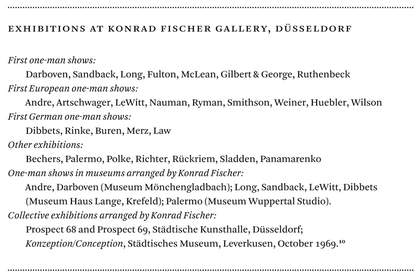

In a chart compiled to introduce the interview with Jappe, Fischer listed his record of ‘firsts’ (table 2). Fischer did not explain in the Studio International interview the relationship between his ‘firsts’ and his network. His strategy was to gain a small percentage from sales to galleries across Europe. This enabled him to have the time to co-curate museum shows to increase his artists’ reputation. The best interests of his artists were served by enabling sales from galleries in different cities, from which he gained only a small commission. This also explains Fischer’s ability to co-curate museum shows. He thought the job of the dealer was to do the work for museum curators in order to show his artists. This was more important than individual sales. Richard’s research demonstrates that this business concept underpins the early success of conceptualism in Europe and was at the heart of its development in the first decade. What Richard’s databases reveal is the increasingly central role economics plays in recent art history.

Table 2

I have made an additional list of the defining mixed exhibitions of conceptual art in both public galleries and museums and in dealer galleries (table 3). I have highlighted those exhibitions that were organised by what I have called ‘dealer curators’. It shows that more than fifty per cent of the defining exhibitions of conceptual art in public galleries, museums and dealer galleries were organised by ‘dealer curators’. Half of that fifty per cent were organised by Fischer. This reinforces the correlation between a dealer curating exhibitions and sales made to public collections.

I discussed with Richard an example, from my own experience, of Fischer’s central, but concealed role. I worked at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London as the touring exhibition When Attitudes Become Form, organised by Harald Szeemann, was installed there in 1969.9 It was the experience of working with artists rather than objects that I have sought to pass onto future generations with the EAST international exhibitions in Norwich. Many of the artists in When Attitudes Become Form had been in Fischer’s Prospect 68 in Düsseldorf. A letter to Fischer from Charles Harrison, the curator of the ICA showing, thanks him for his assistance in the preparation of ;When Attitudes Become Form for the ICA and asks for instructions on how to install the work of a number of artists.10 Szeemann was busy organising Happenings and Fluxus for the Kunsthalle and Kunstverein in Cologne and he only arrived in London in time to make the opening speech. Harrison was also busy, teaching at St Martins and working at Studio International during the installation. The person who had his coat off, rolled up his sleeves and worked with the artists and the installation teams untilHarrison arrived in the afternoon was Fischer.

Hans Strelow defended Fischer’s role as a dealer-curator. Together, they curated the Düsseldorf series of Prospect exhibitions in 1968, 1969, 1971, 1973 and 1976. In an interview with Brigitte Kölle, Strelow said: ‘We had 20,000 marks at our disposal for the first exhibition … Konrad and I prepared the show for months, without being paid a fee … Konrad and I compiled a list of artists we thought should take part in the exhibition and then sent the list to the jury … We organised the exhibition in a public institution and we felt obliged to objectivity. Therefore, commerce played no part whatsoever’.11

In spring 1969, Fischer went to New Yorkto prepare the Prospect 69 exhibition for the Kunsthalle and Kunstverein in Düsseldorf. He made a good impression. A letter dated 7 May 1969, quoted by Richard, from Marilyn Fischbach to Fischer concerning Robert Ryman suggests: ‘You could be the central European gallery connection … and you could distribute the work in Europe … The commission could be 25 per cent to you, which leaves little to us, actually only 15 per cent’.12 However, an agreement was not reached. In the autumn, Ryman had exhibitions with the European dealers Heiner Friedrich, Françoise Lambert, Yvon Lambert, Franz Dalem and Gian Enzo Sperone. This shows the development of a network for US artists across Europe, linked to Düsseldorf. Richard’s databases show fewer sales for Ryman than for LeWitt and Nauman: their prices averaged $3–4,000, while Ryman’s averaged $15–16,000. The Italian collector Giuseppe Panza bought seventeen works by Ryman between 1971 and 1974, probably spending well over $250,000 at early 1970s prices.

Fischer’s influence in the US can also be illustrated by another example. In November 1969, the curator Diane Waldman wrote to Fischer that she was planning a research trip to see younger German artists for a Guggenheim exhibition in New York. Waldman lists Joseph Beuys, Reiner Ruthenbeck, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Jörg Immendorff, Klaus Rinke, Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke. Her Guggenheim International opened in February 1971 and included eleven of the artists on Fischer’s Studio International list of ‘Firsts’. None of the artists on her original list survived her consultation with Fischer.

An important exhibition curated by Fischer, with Klaus Honnef, was section 17 of documenta 5, Idee+Idee/Licht of 1972. It was a small section of the show, but as Honnef discussed with Richard in an interview in 2005:

My feeling was that I could still learn a few things and I opted to work with Fischer … It was a very intense collaboration. I worked very intensively with him on exhibitions in Münster, and he cooperated with me very closely on the book [Concept Art, London, 1971] … For Harald Szeemann it wasn’t his favourite section … he thought it was a bit too cerebral … Of course the specialists, the insiders, thought that our section – that big room with the Circle by Richard Long in the middle, and Darboven and Sol LeWitt opposite, and also Agnes Martin – was the Cathedral of documenta, along with Richard Serra, who was in the next room … Fischer was very meticulous about the budget. We only had a little B&B on the outskirts.

Johannes Cladders discussed the issues around the dealer-curator with Brigitte Kölle:

BK: Wasn’t it a bit disreputable that Konrad, as a gallery owner, conceived a section of the documenta and also displayed artists from his own gallery?

JC: Konrad was appointed a chaperone, Klaus Honnef … [laughs] I’m not aware that anyone objected … Of course he was interested in selling … But selling was not his main intention.13

Richard’s meticulous research shows us that because he was a dealer, Fischer’s role has been concealed behind ‘the objectivity of curators’ like Szeemann, Honnef and Cladders.

I have also made a comparative chart from Richard’s data on dealer sales to museums between 1967 and 1980 (table 4). This shows, at least from the data available to Richard, that Fischer controlled a quarter of all sales to public collections of conceptualism in Europein the first decade. However, I would argue that Fischer was building on the model of Marcel Duchamp’s role as an artist/dealer/curator.

An exchange of letters between Fischer and Sol LeWitt in November 1967, reproduced in the first chapter of Richard’s book, reveals the percentage arrangements not only between artist and dealer but also to other dealers across various European cities. TheUSartists were passed around the European galleries in a franchise arrangement. On 22 November 1967 Fischer writes [with curious mathematics]: ‘The Percentage: 50 per cent for the artist, 50 per cent for the gallery, 30 per cent for the other gallery and 50 per cent for you … when the show is taken to another place. I think there should be 20 per cent for my gallery’.14 However, this only applied to the works shown by Konrad Fischer.

In Brigitte Kölle’s book Okey Dokey Konrad Fischer, Bruce Nauman discusses the relationship between American and European galleries: ‘Carl [Andre] and Sol [LeWitt] both had shows in the States but nobody bought anything. They were much more accepted inEurope … Konrad still sold more work inEurope than was sold in theUS. Prices were very low. I think the fact my dealers – Dick Bellamy and Leo Castelli – had my work inNew York gave me a lot of credibility.’15

There are differences between US and European perceptions of the development of conceptual art, influenced by diverging cultural agendas. There are also significant differences in the order in which work was seen on either side of the Atlanticbetween 1968 and 1973. Anti-American demonstrations at the Venice Biennale and documenta in 1968 asked: ‘What else remains for the artists of a nation which wages such a criminal war as that in Vietnam but to produce minimal art?’ Europe continued to show American minimal sculpture, especially those sculptors whose critical and theoretical writings blended into radical language-based and documentary photographic and video conceptualism. Minimal painting was not shown a great deal in Europe until after 1973.16 The American understanding of the development of formalist minimalism into conceptualism was therefore different to the European understanding of a combination of Fluxus and Pop developing into a theoretical, political conceptualism.

When Prospect 73, subtitled Malers Painters Peintres, opened in Düsseldorf in 1973, it shocked those of us who had thought of Prospect as an idealistic and progressive force for radical conceptualism. A survey of painting over the previous fifteen years, it included the European premiere of Emile de Antonio’s film Painters Painting, The New York Art Scene 1940–1970 (1972), which reinforced the idea of a continuous development from American abstraction to Pop to minimalism.17 This was the first time I heard the term ‘conceptual painting’ used. Prospect 73 focused attention not only on Robert Ryman, Brice Marden, Dorothea Rockburne and Agnes Martin, but also on the painters with whom Fischer had studied at the Düsseldorf Akademie in the early 1960s: Gerhard Richter with his new minimalist colour-chart paintings and Sigmar Polke with his large-scale montage paintings.

The prices quoted in Richard’s databases give us this clear example of commercial interests controlling the direction of contemporary art. It could be argued that Fischer had developed radical conceptual art in Europewith Prospect in 1968, 1969 and 1971, but had then betrayed it with a return to minimal painting in 1973. In mitigation, Fischer appears to have used the profits from the sales of works by US minimalist painters to develop the careers of his European artists.18

I worked for Nigel Greenwood from July 1971 to May 1974 and I saw Fischer frequently in Londonand at art fairs and openings across Europeand New Yorkthroughout the 1970s. I met him again in 1993, when he came to Norwichto select the third east exhibition for me. This gave me the opportunity to ask him about the difference between my memories of conceptualism and recent published accounts. As a result of those conversations, I began to trust my memories. However, I knew that my knowledge of Fischer’s role would not be accepted as an objective record. The years spent working with research students like Moseley and Richard since Fischer’s death in 1996 have meant that my account has been thoroughly examined and verified by the facts; ‘unconcealed’ by a new generation of art historians in archives, documents and interviews.

I will finish by summarising the points I have made as a result of my analysis of Richard’s databases. There is a correlation between a dealer curating mixed exhibitions in public spaces and their sales to public collections in the period between 1967 and 1977 shown by a comparison of the two aggregate databases created for my introduction. This suggests museums thought as much about the dealer they were buying from, as the work they were acquiring. Museums believed artists made their best work for dealers who also curated exhibitions for public spaces. Richard has collected significant evidence that ‘dealer curators’ represented the private galleries that museums acquired the most works from in the period 1967 to 1977.

The early success of conceptual art was based on the co-ordination of European tours for US artists. Galleries shared expenses and also in some cases shared the commission on sales. This idea appears to have been developed by Konrad Fischer in Düsseldorf with Heiner Friedrich inMunichand John Weber at Dwan Gallery in New York. The sales of work by US artists allowed European dealers to support the careers of less established European artists. European artists were included in mixed museum exhibitions of conceptual art co-curated by dealers. Dealers were able to arrange exhibitions for their less established European artists in the European network created for US artists. Finally, the funds European dealers acquired from sales of US artists to European museums enabled them to support the careers of younger European artists.

Sophie Richard’s unconcealing of the economic-critical history of conceptual art is a new step in the research of this important period. I am sure that Richard’s study will inspire future generations of curators and art historians and inform the development of professional standards in museums and public galleries, as they delve deeper into the history of conceptual art.